A comprehensive dataset of Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Xiangjie Kong

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning

- Keywords

- Facial expression, Infant, Intensity, Pain, Dataset

- Copyright

- © 2026 Khan et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. A comprehensive dataset of Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e2929 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.2929

Abstract

Facial expressions are critical for interpreting and diagnosing internal emotional states, particularly in clinical contexts. Recognition and accurate assessment of pain-related facial expressions are essential for effective patient care. Existing datasets primarily represent adult pain expressions, with comparatively fewer resources dedicated to infant pain. This study introduces the Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity (IFEPI) dataset, which categorizes infant pain into four levels: no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, and severe pain. The dataset comprises 25,000 spontaneous images collected from 120 infants at two hospitals in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, both affiliated with the Health Department of the Government of Pakistan and the World Health Organization (WHO). The methodology encompasses environment setup, image acquisition, preprocessing, and image refinement. The IFEPI dataset is currently the largest available dataset for pain-related facial expressions. To validate the dataset, four machine learning models–logistic regression, support vector machine (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and random forest–were employed, alongside eight deep learning models: LeNet, AlexNet, Visual Geometry Group-16 (VGG-16), Inception Version 3 (InceptionV3), Densely Connected Convolutional Network-121 (DenseNet121), Densely Connected Convolutional Network-201 (DenseNet201), Efficient Convolutional Neural Network-B0 (EfficientNetB0), and Efficient Convolutional Neural Network-B7 (EfficientNetB7). DenseNet201 achieved training and testing accuracies of 93.37% and 94.95%, respectively, while EfficientNetB7 achieved training and testing accuracies of 96.82% and 94.61%, respectively.

Introduction

Facial expression analysis is a significant area of research in affective computing, focusing on recognizing and interpreting human emotions through facial cues. Facial expression recognition aims to categorize images into six basic types–happy, fear, neutral, sad, surprise, and disgust–proposed by Ekman (1976). While some proposals suggest eight basic emotions, it is important to note that fear and anger are distinct emotions. The relationship between emotions and pain is complex and bidirectional. Pain is not inherently an emotion. However, it often elicits strong emotional responses such as fear, anxiety, or distress. Conversely, emotional states can influence the perception of pain, either amplifying or diminishing its intensity. For example, stress or negative emotions may lower the pain threshold. This makes individuals more sensitive to painful stimuli. Positive emotions can sometimes mitigate the experience of pain. To further explore this interplay, it is useful to examine physiological markers such as facial expressions. These provide insights into pain thresholds. Specific facial features, like furrowed brows, tightened eyelids, or a raised upper lip, are commonly associated with pain. They can serve as indicators of an individual’s pain experience (Bartlett et al., 2014). Integrating these observable cues with emotional context enables a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between pain and emotion. This topic has garnered significant attention in computer vision, psychology, and affective computing in recent years (Sariyanidi, Gunes & Cavallaro, 2015; Gunes, Piccardi & Pantic, 2008; Zeng et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2014b; Chen et al., 2011; Shan & Braspenning, 2010). Previous works in facial expression recognition share three key characteristics (Sariyanidi, Gunes & Cavallaro, 2015; Gunes, Piccardi & Pantic, 2008; Zeng et al., 2009; Shan & Braspenning, 2010; Soleymani et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2014a; Poria et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2016; Zheng, 2014; Zong et al., 2018). Firstly, research predominantly targets adults, with limited focus on children or infants (Sariyanidi, Gunes & Cavallaro, 2015; Zeng et al., 2009; Shan & Braspenning, 2010; Brahnam et al., 2006; Brahnam et al., 2007). Given the substantial differences in facial expressions between adults and children, especially infants, adopting existing recognition methods for children or infants is a significant challenge (Lu, Li & Li, 2008; Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Brahnam, Nanni & Sexton, 2007; Zamzami et al., 2015). Secondly, facial expression recognition primarily targets six basic emotions: happy, sad, disgust, surprise, fear, and anger. There is limited exploration of non-basic expressions, such as pain in infants and contempt (Brahnam et al., 2006; Lu, Li & Li, 2008; Lu et al., 2008; Zamzmi et al., 2016; Zamzmi et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2016; Bänziger, Mortillaro & Scherer, 2012; Zhong et al., 2015). Thirdly, most facial expression recognition studies rely on staged facial images, often from film clips or controlled experiments. Several studies, like Lecciso et al. (2021), are examining methods for teaching children to express their fundamental emotions effectively in specific situations. Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience. It is associated with, or resembles, that from actual or potential tissue damage. In recent years, recognizing infants’ pain through facial expressions has emerged as a challenging yet vital research area in computer vision, life sciences, affective computing, and neuroscience. Despite its significance, progress has been hindered by the scarcity of large, dependable datasets on infants’ pain expressions. Consequently, studies on this subject remain rare, and advancements have been slow. Nevertheless, the importance of accurately identifying pain expressions, particularly in infants, has led to an increased research in medical and neuroscience circles. Multiple studies have affirmed that facial expressions provide the most reliable cues for assessing infants’ pain (Brahnam et al., 2006; Brahnam et al., 2007; Lu, Li & Li, 2008; Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Brahnam, Nanni & Sexton, 2007; Lu et al., 2008; Zamzmi et al., 2017; Grunau, Holsti & Peters, 2006; Grunau et al., 1998; Duhn & Medves, 2004; Sikka et al., 2015). While pain typically has a lesser impact on adults, it often leads to varying levels of influence or harm in infants. These effects may include developmental delays and damage the central nervous system. The severity and duration of pain directly affect its impact on infants. Severe and prolonged pain can have more significant consequences. Milder pain produces comparatively less impact. In clinical practice, doctors address these influences or damages by implementing pain management strategies tailored to the type and severity of pain (Brahnam et al., 2006; Brahnam et al., 2007; Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Grunau, Holsti & Peters, 2006; Grunau et al., 1998; Schmelzle-Lubiecki, 2007). For infants experiencing severe pain, pediatricians might administer pharmacological analgesics. For mild to moderate pain, nonpharmacological approaches, such as providing sucrose solutions, may be used. In all cases, a thorough pain assessment must be conducted to accurately determine pain levels before applying pain management techniques.

Problem statement

Most existing frameworks for identifying emotion and pain intensity are based on adult facial datasets, which capture the nuanced dynamics of mature faces, rather than datasets focused on children or infants (Stevens, 1990). This lack of infant-specific datasets presents two primary challenges. First, the practical benefits of evaluating infant facial expressions remain under-recognized, despite their potential applications in scientific parenting and intelligent childcare. Second, acquiring infant facial datasets with precise expression labeling is particularly challenging (Lin, He & Jiang, 2020). Common pain-related facial expressions in children include grimacing, eye closure, a quivering chin, and a stretched open mouth, with these indicators providing the most reliable cues for infant pain assessment (Ballweg, 2008). However, there is a notable absence of large, spontaneous, real-time datasets capturing pain-related facial expressions during venipuncture in infants aged 2 to 12 months. To date, no publicly available dataset addresses the four levels of pain intensity in this age group, and no artificial intelligence framework has demonstrated substantial accuracy on the existing but limited datasets.

Proposed solution

This study presents a comprehensive and rigorously curated dataset, the Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity (IFEPI), which constitutes the largest available collection of infant facial expressions of pain intensity. The dataset comprises 25,000 facial expression images, evenly distributed across four pain levels: no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, and severe pain, with 6,250 images per category. Data were collected from two hospitals in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, and ensuring diversity within the sample. The scale and balance of this dataset are expected to improve the generalizability and validity of artificial intelligence frameworks for pain assessment. To validate the dataset, four machines learning algorithms and eight deep learning algorithms were applied, demonstrating its suitability for supporting advanced artificial intelligence (AI)-based pain recognition in infant.

Contribution of paper

-

To develop the largest populated facial expression pain dataset of infants, named the Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity (IFEPI).

-

To develop a dataset containing four pain intensity level facial expression images.

-

To establish baseline models, demonstrate higher accuracy when evaluated on a large dataset compared to smaller datasets.

Following on from the remainder of this work, ‘Related Work’ will discuss the related work on the classification of intensity of pain. ‘Materials & Methods’ presents the data description, and ‘Results’ describes the experimental work of the proposed research approach and analyzes the obtained results. Finally, ‘Conclusions’ will conclude this work.

Related Work

Identifying infants’ pain is undeniably crucial, but it remains a formidable challenge (Brahnam et al., 2006; Brahnam et al., 2007; Lu, Li & Li, 2008; Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Lu et al., 2008; Zamzmi et al., 2017; Werner et al., 2019). Currently, the prevailing approach for assessing pain relies on manual coding techniques. This entails employing tools like the Neonatal Facial Coding System (NFCS) (Grunau, Holsti & Peters, 2006; Grunau et al., 1998) or the Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS) (Lawrence et al., 1991) to assign a pain score to the neonate. Subsequently, based on this score, healthcare providers ascertain whether the infants are experiencing pain and the level of its intensity. Relying on manual coding for pain assessment may introduce subjectivity, as different studies might interpret the same pain expression with bias. Additionally, it is essential to recognize that manual coding-based pain assessment methods can be time-consuming and may not meet the requirements of real-time evaluation (Brahnam et al., 2007; Lu, Li & Li, 2008; Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Zamzmi et al., 2017). To address these shortcomings of old-style manual coding approaches, incorporating programmed facial expression recognition into infants’ pain assessment is imperative. This underscores the need for establishing a dedicated infant pain dataset to facilitate research in automatic pain expression recognition for infants’ pain assessment.

In essence, most recently developed facial expression datasets primarily focus on adult subjects, thereby creating a gap in the representation of other age groups. The BioVid (Walter et al., 2013), Picture of Facial Affect (POFA) (Ekman, 1976), the Extended Cohn–Kanade (CK+) (Kanade, Cohn & Tian, 2000; Lucey et al., 2010), STOIC (Roy et al., 2009; Hammal et al., 2008), the Japanese Female Facial Expression (JAFFE) (Lyons, Budynek & Akamatsu, 1999), M&M Initiative (Pantic et al., 2005), Binghamton University 3D Facial Expression (BU-3DFE) (Yin et al., 2006), Multi Pose, Illumination, and Expression (Multi-PIE) (Gross, 2008), and the University of Northern British Columbia-McMaster (UNBC-McMaster) (Lucey et al., 2011) are just a few examples. Among these datasets, only a limited set is dedicated to pain expressions, for instance, the UNBC-McMaster, STOIC, and BioVid datasets. The UNBC-McMaster (Lucey et al., 2011) dataset captures adult expressions of pain. It contains 200 video clips and 48,398 images from 25 participants, covering a range of emotions, including both painful and non-painful expressions. Similarly, the STOIC dataset (Roy et al., 2009) is a collection of facial expressions focusing on pain although it primarily includes posed rather than spontaneous expressions of pain. In addition to expressions of pain, the dataset has videos showing six basic emotions and a neutral expression. The STOIC dataset comprises a total of 1,088 videos from 34 adults, approximately 130 of which depict expressions of pain. The BioVid (Walter et al., 2013) dataset centers on facial expressions in response to heat-induced pain among adults. However, it is worth noting that facial expressions in these three widely used pain expression datasets are exclusively derived from adult subjects.

In contrast, neonatal pain has been investigated through the Classification of Pain Expressions (COPE) (Brahnam et al., 2005), YouTube (Harrison et al., 2014), Acute Pain in Neonates database (APN-db) (Egede et al., 2019) and Facial Expression of Neonatal Pain (FENP) (Yan et al., 2023) datasets. The COPE (Brahnam et al., 2005), a reputable public resource, comprises a total of 204 facial expression images capturing neonatal pain from 25 subjects. Among these, 60 images depict severe pain, while 144 highlight non-pain expressions. The YouTube (Harrison et al., 2014) dataset is also available as a public resource for neonatal pain expressions, encompassing 142 videos sourced from uploads by parents, nurses, and other caregivers. The APN-db (Egede et al., 2019) dataset offers a freely available repository of neonatal pain facial expressions, comprising over 200 labeled videos of infants displaying various levels of pain intensity. The recently published FENP dataset (Yan et al., 2023) primarily focuses on neonatal pain levels. Although it has increased to a considerable size, featuring 11,000 facial images, it is noteworthy that it exclusively incorporates two pain levels. Zamzami et al. (2015) created a collection of videos showing the facial expressions of newborns experiencing pain. This dataset includes 10 videos featuring 10 different newborns. While these datasets are considered accessible and trustworthy, they suffer from limited sample sizes and inadequate coverage of multiple pain intensities. Most datasets reduce pain representation to either a binary classification (pain vs no pain) or at best, two levels of intensity, failing to capture the complexity of infant pain responses.

In addition to these facial expression datasets, several multimodal datasets have been introduced to study the perception of pain. The Pain dataset, X-ITE (Othman et al., 2021), is a collection of diverse information about pain. It includes facial expressions, body movements, and signals from the body’s functions. This dataset is designed to focus on the differences in the intensity and duration of pain experienced by individuals. The Multimodal Intensity Pain (MIntPAIN) dataset (Haque et al., 2018) includes 9,366 videos and 187,939 images with multimodal features such as depth and temperature recordings from 20 participants. Similarly, the SenseEmotion (Velana et al., 2016) is a multimodal dataset that includes facial expressions, body information, and sounds. This dataset comprises approximately 1,350 min of recordings from 45 participants. The EmoPain dataset (Aung et al., 2016) focuses on patients with chronic lower back pain, featuring videos, sounds, muscle signals, and body movements from 21 patients and 28 healthy controls. The Binghamton-Pittsburgh 3D Dynamic (BP4D) dataset (Zhang et al., 2014) also incorporates naturalistic expressions, including pain, alongside basic emotions such as happiness, sadness, anger, and surprise. These datasets, while comprehensive, again do not address the need for infant pain recognition, as the participants are adults in these datasets.

To address these limitations, the proposed IFEPI dataset offers several advantages over existing pain-related facial expression datasets. Unlike neonatal datasets such as COPE (Brahnam et al., 2005) and FENP (Yan et al., 2023), which focus only on very early life (18 h to 4 weeks), IFEPI spans infants aged 2 to 12 months, ensuring broader developmental coverage and greater generalizability across growth stages. With 25,000 images, it is significantly larger than COPE (204 images), Zamzami (10 videos), YouTube (142 videos), and even FENP (11,000 images), thus providing higher robustness for training machine learning and deep learning models. Moreover, while datasets like UNBC-McMaster (Lucey et al., 2011) and STOIC (Roy et al., 2009) restrict classification to binary categories (pain vs no pain), and FENP (Yan et al., 2023) includes only two intensity levels, IFEPI uniquely introduces four graded pain intensity levels (No Pain, Mild, Moderate, Severe), enabling more fine-grained and precise recognition. Importantly, unlike STOIC (Roy et al., 2009), which largely includes posed expressions, IFEPI captures spontaneous, real-time pain reactions during vaccination procedures, enhancing ecological validity and clinical applicability. Additionally, whereas most datasets either lack ethnic diversity (UNBC-McMaster, STOIC, and YouTube) or are dominated by single groups (COPE/FENP), IFEPI specifically represents Pashtun infants, addressing an underrepresented ethnicity and contributing to global dataset diversity. Finally, although adult pain datasets such as BioVid (Walter et al., 2013) and UNBC-McMaster (Lucey et al., 2011) are comparatively larger, they cannot be generalized to infants due to morphological and expressive differences, making IFEPI the first large-scale dataset dedicated to infants aged 2–12 months and filling a crucial gap in infant pain research. Table 1 provides a comparison between the existing dataset and the proposed dataset.

| Database | Age | Subjects | Samples | Categories | Race |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFEPI (proposed) | 2 to 12 months | 120 | 25,000 images | No Pain, Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, Severe Pain | Pashtuns |

| UNBC-McMaster (Yin et al., 2006) | Adults | 25 | 48,398 Images | Pain, No Pain | Unknown |

| STOIC (Kanade, Cohn & Tian, 2000) | Adults | 34 | 1,088 Images | Pain, No pain | Unknown |

| BioVid (Werner et al., 2019) | Adults | 90 | 180 Videos | Mild, Moderate, No, Calm | German |

| Cope (Gross, 2008) | 18 h to 3 days | 26 | 204 images | Pain; Friction; Air Stimulus; Cry; Rest |

Caucasian |

| Zamzami (Brahnam, Nanni & Sexton, 2007) | About 36 weeks | 10 | 10 videos | Acute Pain; Chronic pain | Caucasian; Hispanic; African American; Asian |

| YouTube (Lucey et al., 2011) | 0, 2, 4, 6 or 12 months | Unknown | 142 videos | Pain | Unknown |

| FENP (Brahnam et al., 2005) | 2 days to 4 weeks | 106 | 11,000 Images | Calmness, Cry, Mild pain, Severe Pain | Chinese |

Materials & Methods

When constructing the IFEPI dataset, we considered the limitations of existing pain expression datasets. While adult datasets such as UNBC-McMaster are large-scale, whereas neonatal pain datasets like COPE and FENP remain relatively small due to the inherent difficulty of capturing spontaneous infant pain expressions in real-world environments. To address this gap, we collected spontaneous facial expressions during vaccination procedures, ensuring that the dataset reflects naturalistic pain responses rather than posed expressions.

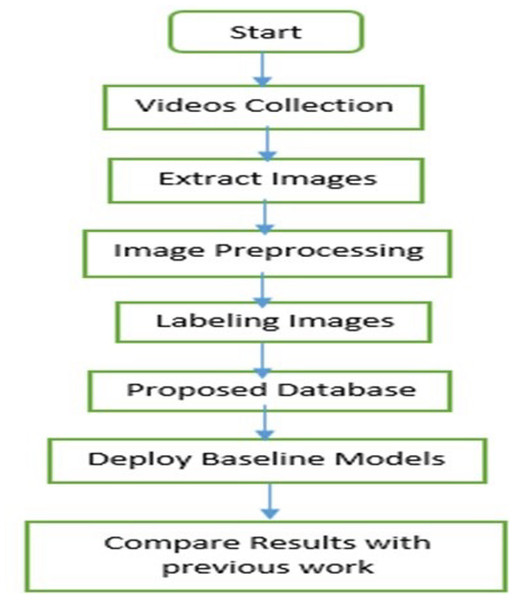

Over the course of two years, we diligently gathered data on infants’ facial expressions of pain, in collaboration with child vaccination centers affiliated with the Federal Directorate of Immunization, Pakistan, and the World Health Organization (WHO). As a result, we successfully established an extensive dataset comprising 25,000 images of infants in pain. A comprehensive overview of the dataset is provided in the subsequent sections. Figure 1 illustrates the methodology employed for the IFEPI dataset development.

Figure 1: Flowchart of the proposed methodology.

Data collection

We utilized two devices for data collection: an OPPO A1K smartphone with a resolution of 720 ×1,560 and a SAMSUNG GALAXY S20 with a resolution of 1,440 ×3,200. These devices were used to capture facial videos and images of infants’ facial expressions during routine vaccination procedures in the vaccination rooms of the Child Vaccination Center, which is affiliated with both the Federal Directorate of Immunization and the World Health Organization (WHO). The selected vaccination centers are in Mercy Teaching Hospital, University Road, Peshawar, Pakistan and Kuwait Teaching Hospital, University Road, Peshawar, Pakistan. For dataset collection, sites are situated in the capital of the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan—namely Peshawar. Figure 2 provides a visual of the data collection environment in the vaccination room of Kuwait Teaching Hospital.

Figure 2: Vaccination room data collection in Kuwait teaching hospital.

During the collection of many data instances, we utilized the OPPO A1K smartphone due to its convenience. Given the demanding schedules of nurses and doctors in the actual vaccination environment, who often need to attend to various tasks while documenting infants, the OPPO A1K proved to be a practical and accessible tool for them.

A written consent form is obtained from the parent or guardian of each infant, in which the purpose and objectives of the research are clearly explained. This written consent form also assures parents that their child’s identity and personal information will remain confidential throughout the study, with appropriate safeguards in place to prevent disclosure. Additionally, the written consent form informs parents of their right to withdraw their consent at any time, without any repercussions. An official written approval was obtained from Institutional Bioethics Committee, Institutional Review Board, Office of Research, Innovation, and Commercialization (ORIC), with reference number 994/ORIC/ICP at Islamia College Peshawar (Chartered University), to ensure compliance with ethical standards and guidelines for the study.

The Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity (IFEPI) dataset encompasses four primary pain emotion categories: No Pain, Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, and Severe Pain. To obtain videos corresponding to each emotion category, we carefully selected settings that accurately represented the actual vaccination environment. Drawing inspiration from the scenario designs in the COPE dataset (Brahnam et al., 2005), and considering the practical layout of the vaccination center, we opted for the following scenarios for video collection:

-

For the pain emotion category (encompassing Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, and Severe Pain), videos were recorded when infants experienced immunization via venipuncture on their arms or legs.

-

To capture the No Pain category, videos were taken while infants were either sleeping or in a calm state (Brahnam et al., 2007; Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Lu et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2015; Gao, 2011; Chen, 2013).

Throughout the process, we aimed to capture as many videos as possible of the frontal facial expressions of neonates. To achieve this, the lens of either the OPPO A1k or the Samsung Galaxy S20 was positioned directly opposite the infants’ faces, allowing it to track their head movements. Given the dynamic nature of the actual vaccination setting, nurses often needed to continue with their tasks while capturing images of the infants. Consequently, the recorded videos occasionally exhibit occlusion issues, such as obstructions from arms, clothing, medical equipment, and instruments. This is particularly noticeable in the emotional categories of Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, and Severe Pain. Ultimately, each video lasts between 25 to 35 s. In Fig. 3 at vaccination center, Mercy Teaching Hospital, Peshawar, an image collected depicting the emotion of the pain category is presented. As explained earlier, it is evident that some frames are partially covered by nurses’ hands, as in Fig. 3. To address this, we employed the Video to JPG converter v2.1.1 tool to extract a series of image frames. From this collection, we manually curated frames that were clear, representative, and free from obstructions, which were then included in the IFEPI dataset as data.

Figure 3: Sample image sequences from pain video in Meercy Teaching Hospital Peshawar Center.

Figure 4: Sample of rotation and cropping of infants image.

Image preprocessing

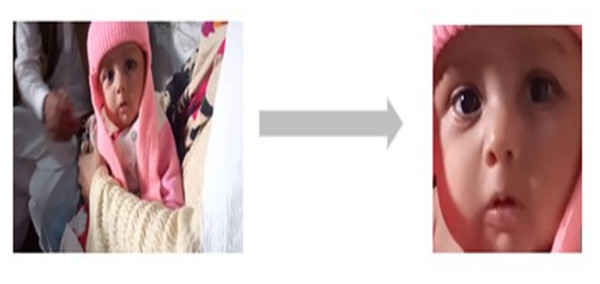

Given the complexity of the actual vaccination environment, the recorded video frequently contains elements that introduce interference, such as occlusions, noise, intricate background details, and variations in lighting. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the background information is intricate and there are notable shifts in lighting. Additionally, the face in the captured infant’s image is not in front of the camera; there is often some degree of angular deflection (Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Gao, 2011; Chen, 2013).

Hence, we adjust the orientation of infant images by a certain degree of angular rotation to ensure their faces are properly aligned. The images were resized to 256 × 256. Following this, we eliminate the background area while preserving the infant’s facial region (Chen, 2013). Figure 4 provides an illustration of the rotation and cropping process for an infant’s image. Subsequently, we apply equalization, grayscale normalization, and scale normalization to the adjusted and cropped infant images (Lu, Li & Li, 2008; Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Lu et al., 2008; Gao, 2011).

Evaluating the pain intensity

Once we have gathered the images of the infants in various settings, we must assign labels to all of them. For the infant images in the No Pain category, we have the labels that we collected when recorded the corresponding infant videos. Since the videos in this category were recorded without any injections, nurses, doctors, and psychologists provide the appropriate labels in real-time during the collection process. However, when it comes to the infants’ images, categorized by pain levels, it is necessary to evaluate the degree of pain and categorize them as mild, moderate, or severe pain. This is essential as the IFEPI dataset aims to construct a comprehensive repository of infant facial expressions depicting varying pain intensities for research purposes.

To ensure an accurate assessment of pain intensity in each infant’s pain image, a team consisting of four nurses, four doctors, and eight psychologists from academia was tasked with manually evaluating the pain levels. They utilized the Neonatal Facial Coding System (NFCS) (Grunau, Holsti & Peters, 2006; Grunau et al., 1998; Duhn & Medves, 2004) to assign scores to each infant’s pain image. To categorize the infant’s pain images into three levels (Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, and Severe Pain), scores between 1 and 3 were assigned to the Mild Pain category, scores between 4 and 6 were assigned to the Moderate Pain category, and scores between 7 and 10 were assigned to the Severe Pain category (Lu, Li & Li, 2008; Guanming, Xiaonan & Haibo, 2008; Lu et al., 2015; Gao, 2011; Chen, 2013).

Due to variations in assessed scores among different doctors, nurses, and psychologists, only the infant pain images with consistent scores were retained while those with inconsistent scores were removed (approximately 75% of images were agreed upon by the raters) (Lu et al., 2016; Chen, 2013).

To address potential biases in manual labeling, a standardized annotation protocol is implemented as described in Lawrence et al. (1991), to ensure consistency across raters (nurses, doctors, and psychologists). Additionally, an inter-rater reliability measure is applied to assess agreement among annotators, minimizing subjective biases. Therefore, for the assessment of inter-rater reliability (IRR) among the raters, Fleiss’ Kappa was employed in the manual labeling process (Fleiss, 1971). This statistical measure was chosen to quantify the level of agreement among multiple raters, while accounting for chance agreement. In this study, Fleiss’ Kappa was applied to assess the reliability of annotations across raters (nurses, doctors, psychologists). Only images that achieved substantial (K = 0.61−0.80) or almost perfect agreement (K = 0.81−1.00) were included in the following dataset, ensuring high quality and reliable data. Images with K < 0.61 were excluded to minimize the inconsistencies in labeling.

Figure 5: The IFEPI database includes samples of No Pain, Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, and Severe Pain.

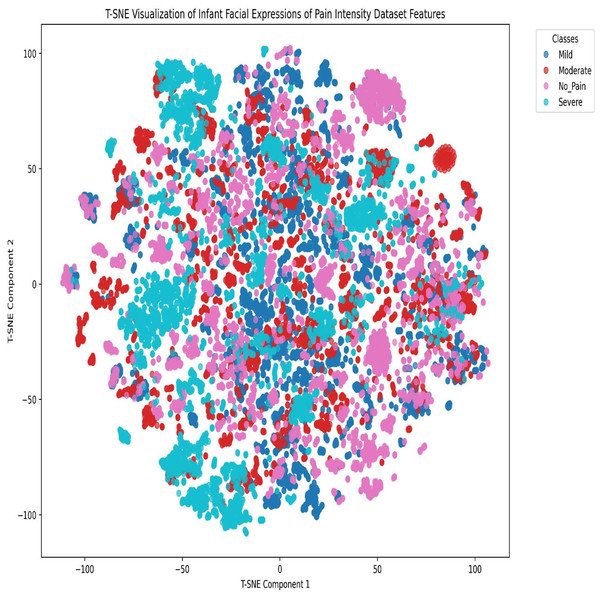

The rows correspond to their respective categories.Figure 6: t-SNE visualization of the Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity dataset features.

Dataset characteristics

Finally, the IFEPI dataset has amassed 25,000 infant facial expression images from 120 Pashtun infants, all aged between 2 to 12 months. These images have a resolution of 256 × 256 and are saved in JPEG format. The dataset encompasses four emotion categories: No Pain, Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, and Severe Pain, each containing 6,250 image samples. Figure 5 shows a sample of images from each category of the proposed dataset.

Additionally, we compared our IFEPI dataset with three other datasets that display facial expressions of pain in adults and newborns, as outlined in Table 1. The table clearly indicates that our IFEPI dataset is significantly larger, with more subjects and sample images, compared to the COPE (Brahnam et al., 2005) and FENP (Yan et al., 2023) datasets. Additionally, the age range of babies in our IFEPI dataset is wider than in the COPE and FENP datasets. Importantly, our IFEPI dataset includes data for four levels of pain (No Pain, Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, and Severe Pain), a feature that the other two datasets lack. Additionally, it is worth noting that our IFEPI dataset primarily focuses on Pashtun infants, while the COPE (Brahnam et al., 2005) dataset primarily examines Caucasian newborns, and the FENP (Yan et al., 2023) dataset concentrates on Chinese newborns.

To analyze class clustering and intra-class feature-space overlap in the final Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity dataset, we employed the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) dimensionality reduction technique. The t-SNE visualization of the Infant Facial Expressions of Pain Intensity dataset features, as shown in Fig. 6, reveals significant feature-space overlaps among the four classes (No Pain, Mild, Moderate, and Severe). Specifically:

-

Cluster overlap: There is substantial intermixing among the classes, particularly between the Mild (blue) and Moderate (red) categories, as well as between No Pain (pink) and the other classes. This suggests that the features extracted by the model do not create well-separated decision boundaries, leading to frequent misclassifications.

-

Densely-populated regions with mixed labels: Several regions contain tightly packed clusters where multiple classes coexist, indicating that the model struggles to differentiate between these expressions, due to subtle variations in facial features.

-

Severe class dispersion: While some severe (cyan) instances form distinguishable clusters, many are still dispersed within other categories, implying that severe pain expressions are sometimes confused with less intense pain levels.

Results

Once the IFEPI dataset has been meticulously constructed, the next crucial step involves conducting comprehensive testing and verification experiments. For this purpose, the dataset is further augmented using rotation, width shift, height shift, shear, zoom, horizontal flip, and fill mode to enhance model generalization and reduce the risk of overfitting. Similarly, the application of cross-validation and standard deviation analysis significantly enhanced the accuracy and reliability (Budiman, 2019) of the models trained on the IFEPI image dataset. By employing k-fold cross-validation, the models were rigorously evaluated across multiple subsets of the dataset, ensuring robust generalization to unseen pain images. The standard deviation of accuracy scores across the folds provided critical insights into the consistency and stability of the models, demonstrating their ability to perform reliably across diverse pain image samples (Murugan, 2018). To ensure the reliability and generalizability of our findings, we have incorporated cross-validation and reported standard deviation in our performance metrics. These additions provide a more robust evaluation of model performance and enhance the credibility of our results.

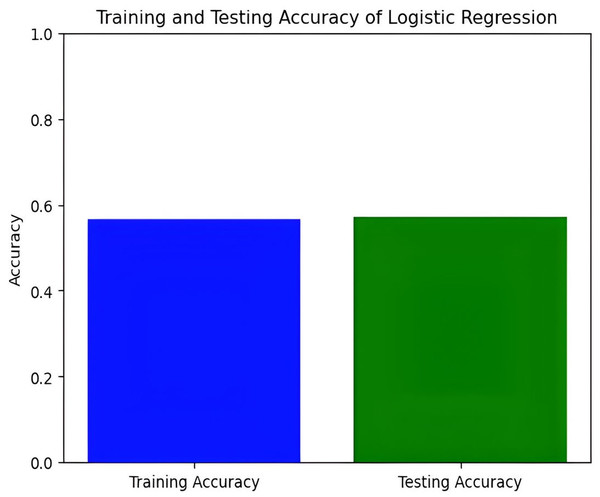

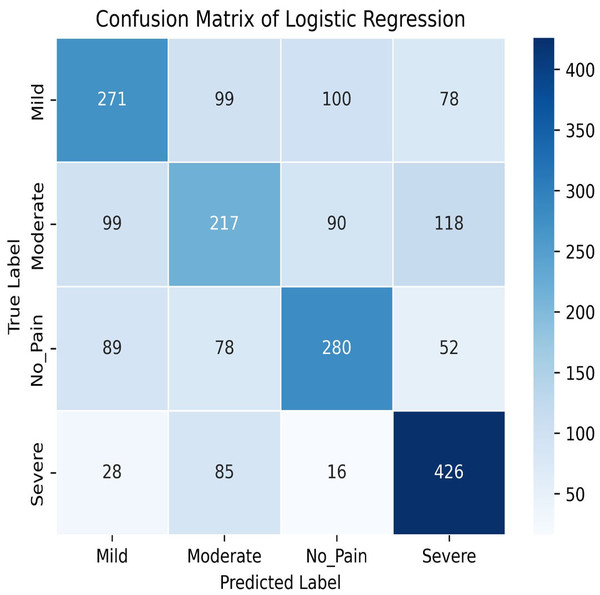

Figure 7: Training and testing accuracy of logistic regression.

Figure 8: Confusion matrix among the Mild, Moderate, No_Pain and Severe expressions using the logistic regression method.

This pivotal phase aims to validate the efficacy and robustness of the IFEPI dataset. To achieve this, a multifaceted approach is adopted, integrating both conventional facial expression recognition methodologies i.e., logistic regression (Song et al., 2023), SVM (Brahnam et al., 2005), K-Nearest Neighbor (Dino & Abdulrazzaq, 2019) and Random Forest (Suryavanshi et al., 2023) and cutting-edge techniques in deep learning such as LeNet (Wang & Gong, 2019), AlexNet (Tureke, Xu & Zhao, 2022), VGG-16 (Simonyan & Zisserman, 2014), InceptionV3 (Szegedy et al., 2014), DenseNet121 and DenseNet201 (Huang et al., 2017), EfficientNetB0 and EfficientNetB7 (Tan & Le, 2019). Through this amalgamation of established and state-of-the-art methodologies, the recognition experiments on the IFEPI dataset are meticulously executed. By leveraging the collective insights gained from traditional methods and the innovative capabilities offered by deep learning frameworks, a comprehensive understanding of facial expression recognition within the context of the IFEPI dataset is achieved. This rigorous experimentation process not only validates the integrity and reliability of the IFEPI dataset but also provides invaluable insights that contribute to the advancement of facial expression recognition technology.

In this study, we delve into the performance evaluation of various machine learning and deep learning models for accuracy prediction (Szegedy et al., 2015). Our investigation commences with the logistic regression model, which achieves a training accuracy of 55.77% and a testing accuracy of 56.16%. Figure 7 illustrates the bar graph depicting the training and testing accuracies of the logistic regression model, while Fig. 8 presents the corresponding confusion matrix. The logistic regression model’s training accuracy of 55.77% and testing accuracy of 56.16% indicate a modest performance. The model’s close alignment suggests that it generalizes well to new data, indicating its robustness and ability to avoid significant overfitting. However, the low accuracies may indicate that the model struggles to capture complex patterns or lacks strong discriminative features. This suggests a need for further refinement, such as feature engineering or exploring more complex algorithms. The confusion matrix for a four-class model provides a detailed assessment of classification performance across different classes. The model performs best in identifying the fourth class, but notable misclassifications are affecting other classes. Analyzing these errors can guide improvements in model performance, such as refining feature selection or employing more sophisticated classification techniques.

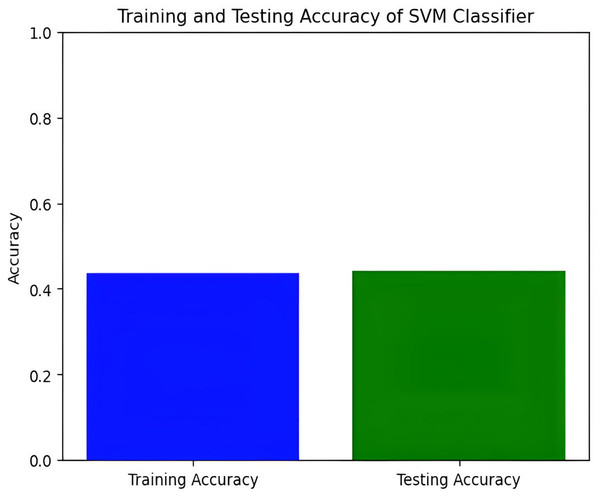

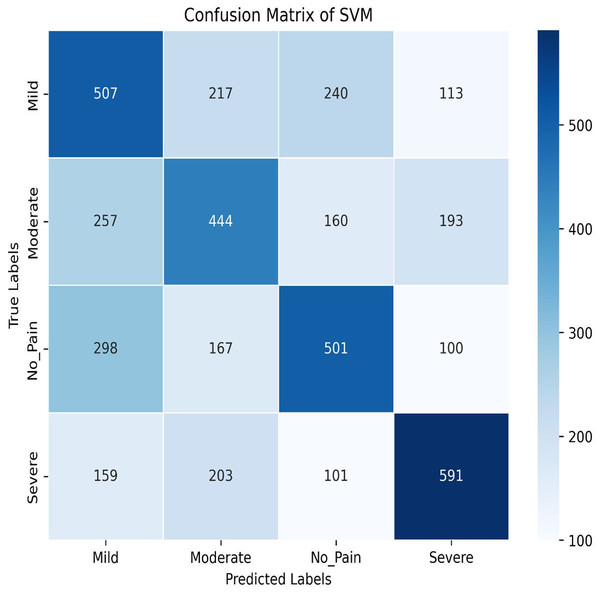

Next, we explore the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model, which achieves a training accuracy of 46.04% and a testing accuracy of 48.06%. Figures 9 and 10 display the bar graphs for training and testing accuracy, along with the associated confusion matrix. A training accuracy of 46.04% and a testing accuracy of 48.06% indicate consistent performance on both datasets. However, low accuracy suggests potential challenges in capturing underlying data patterns. The confusion matrix classifies pain levels into mild, moderate, no pain, and severe pain, with the highest performance in identifying no pain and severe pain classes. Off-diagonal values reveal misclassification patterns, suggesting that the SVM effectively distinguishes between some pain levels but faces confusion, among others.

Figure 9: Training and testing accuracy of SVM.

Figure 10: Confusion matrix among the Mild, Moderate, No_Pain and Severe expressions using the SVM method.

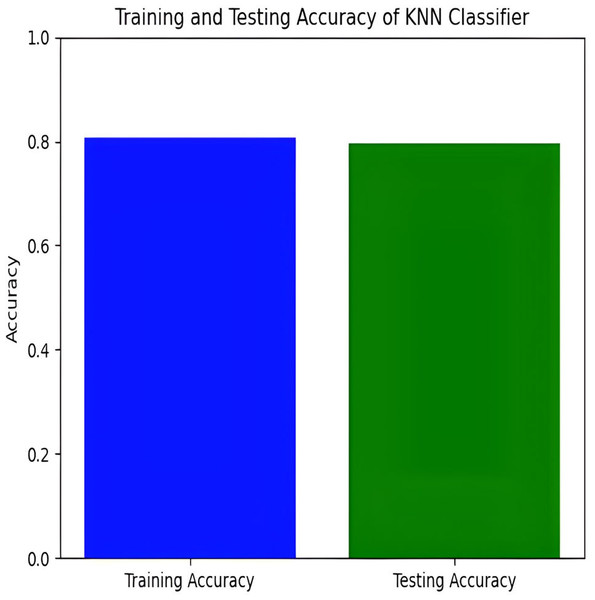

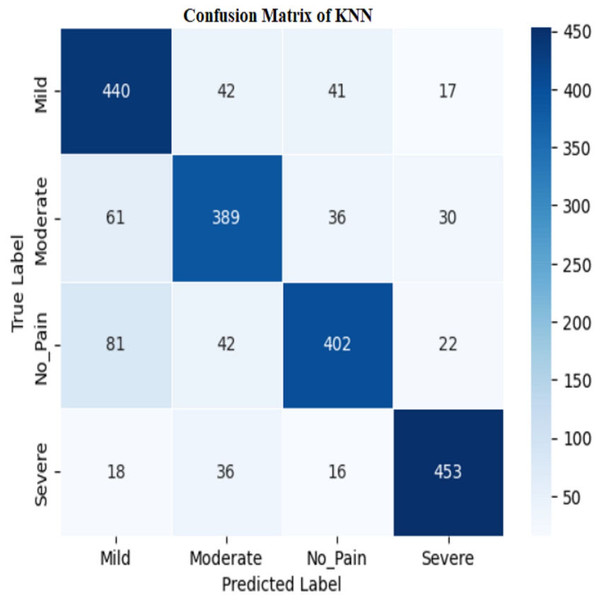

The KNN classifier has a training accuracy of 80.94% and a testing accuracy of 79.21%, indicating effective learning without overfitting as shown in Figs. 11 and 12.

Figure 11: Training and testing accuracy of KNN.

Figure 12: Confusion matrix among the Mild, Moderate, No_Pain and Severe expressions using the KNN method.

The model’s high training accuracy demonstrates its ability to correctly classify most training examples, while a minor drop in testing accuracy suggests consistent performance on new data. However, the model misclassifies instances across different pain levels, such as mild, moderate, no pain, and severe pain. Addressing these misclassification patterns through tuning or enhanced feature selection could potentially improve the classifier’s accuracy and reliability.

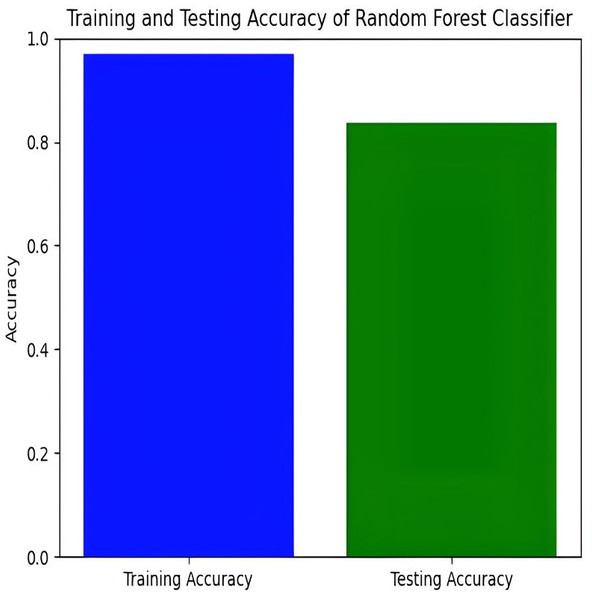

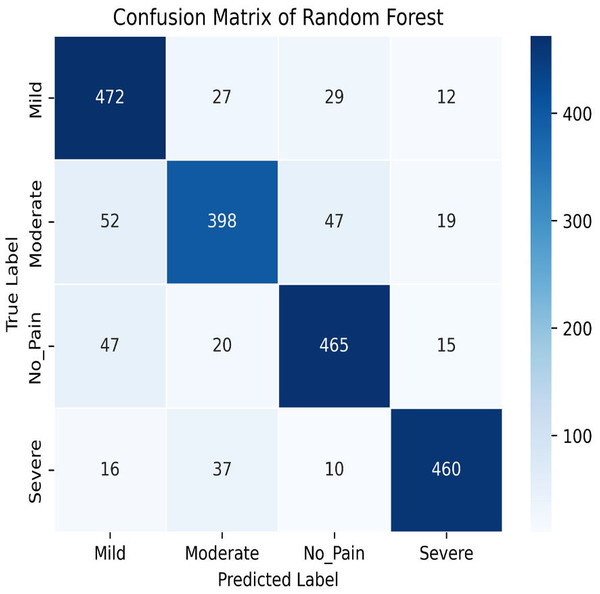

The Random Forest model achieves a training accuracy of 96.91% and a testing accuracy of 79.21%. Figures 13 and 14 provide insights into the training and testing accuracies, as well as the corresponding confusion matrix.

Figure 13: Training and testing accuracy of random forest.

Figure 14: Confusion matrix of random forest.

The Random Forest classifier has a high training accuracy of 96.91% and a testing accuracy of 79.21%, indicating that it performs well on training data but faces challenges in generalizing unseen data. This may lead to overfitting, where the model becomes too tailored to the training data and less effective on new instances. The confusion matrix for the Random Forest classifier across four pain categories shows strong diagonal values, but off-diagonal elements reveal areas of misclassification. For example, mild pain is often misclassified as no pain and moderate pain, while moderate pain is often misclassified as mild and no pain. To improve testing accuracy and mitigate overfitting, further model refinement, such as adjusting hyperparameters or employing regularization techniques, may be necessary.

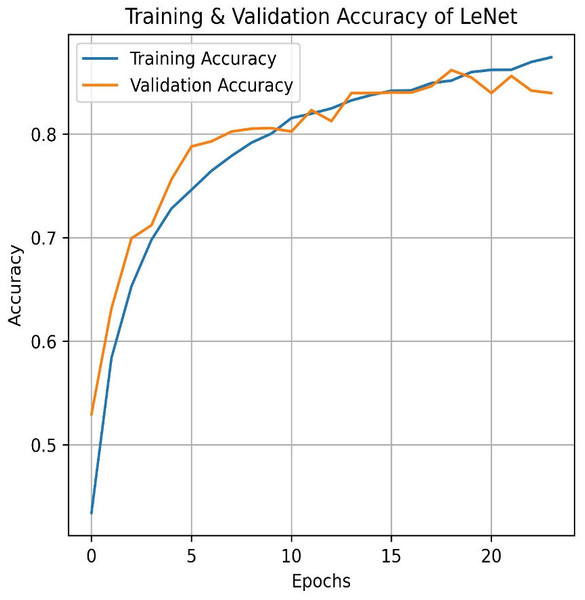

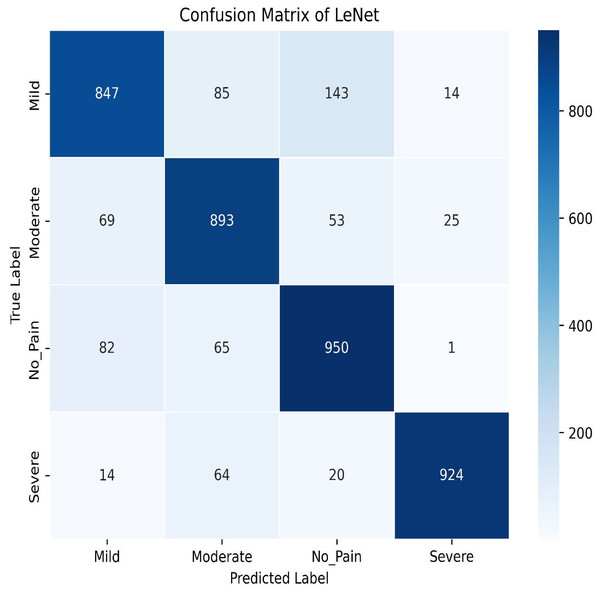

Transitioning to deep learning, we first deployed the LeNet. LeNet achieves an impressive training accuracy of 86.95% and a testing accuracy of 84.87%. Figures 15 and 16 for the accuracy learning curves and the confusion matrix associated with LeNet. LeNet, a pioneering convolutional neural network architecture, has demonstrated robust performance in the classification task involving four categories of pain levels: Mild, Moderate, No Pain, and Severe Pain.

Figure 15: LeNet train and validation accuracy.

Figure 16: LeNet confusion matrix.

The model achieves an impressive training accuracy of 86.95%, indicating its ability to fit the training data. However, its testing accuracy stands at 84.87%, suggesting a noticeable drop in performance when generalizing to unseen data. The confusion matrix further reveals nuanced insights into the model’s classification capabilities. For mild pain, the network correctly identifies 847 instances but misclassifies 85 as moderate pain, 143 as no pain, and 14 as severe pain. For moderate pain, it accurately classifies 893 cases while misclassifying 69 as mild pain, 53 as no pain, and 25 as severe pain. In the no pain category, 950 instances are correctly identified; however, there are 82 misclassified as mild pain, 65 as moderate pain, and one as severe pain. Finally, for severe pain, the network correctly classifies 924 instances but misclassifies 14 as mild pain, 64 as moderate pain, and 20 as no pain. These metrics highlight that while LeNet performs well, there is some overlap in classification between the pain categories, which contributes to the disparity between training and testing accuracies. This suggests areas for potential refinement in model architecture or training procedures to improve generalization and reduce classification errors across different pain levels.

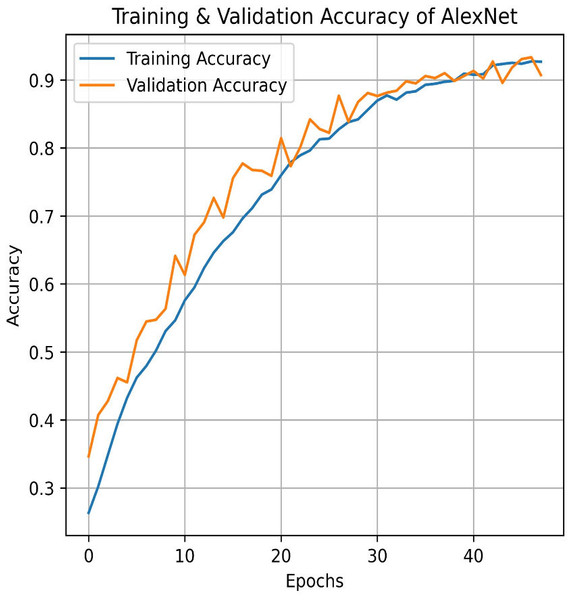

Similarly, AlexNet demonstrates remarkable performance, achieving a training accuracy of 92.70% and a testing accuracy of 90.73%. Figures 17 and 18 visualize the accuracy trends and the confusion matrix for AlexNet. AlexNet, a deep convolutional neural network renowned for its efficacy in image classification tasks, exhibits a high training accuracy of 92.70%, reflecting its strong ability to model the training data with precision. However, its testing accuracy of 90.73% reveals a decrease in performance when applied to new, unseen data, indicating potential challenges with generalization. The confusion matrix provides further insights into the model’s classification performance across four pain categories: Mild, Moderate, No Pain, and Severe Pain. For the mild pain class, AlexNet correctly identifies 1,014 instances but misclassifies 37 as moderate pain, 38 as no pain, and zero as severe pain. In the moderate pain category, the model correctly classifies 980 instances but misidentifies 54 as mild pain, six as no pain, and zero as severe pain. For no pain category, 986 cases are correctly classified, though 87 are misclassified as mild pain, 25 as moderate pain, and zero as severe pain. Lastly, in the severe pain category, 943 instances are accurately identified, with four misclassified as mild pain, 73 as moderate pain, and two as no pain. These results demonstrate that while AlexNet performs robustly on the training set and maintains a solid performance on the testing set, there is still some misclassification across categories. This suggests that, despite its advanced architecture, there may be room for further optimization to enhance accuracy and reduce confusion among different pain levels in the test data.

Figure 17: Train and validation accuracy of AlexNet.

Figure 18: AlexNet confusion matrix.

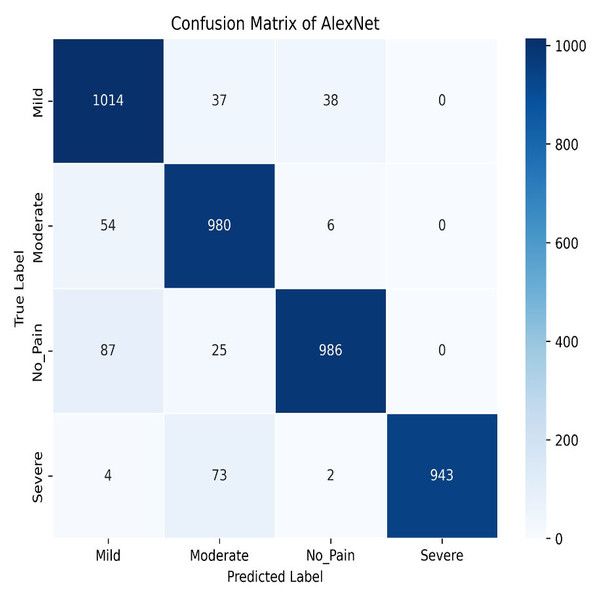

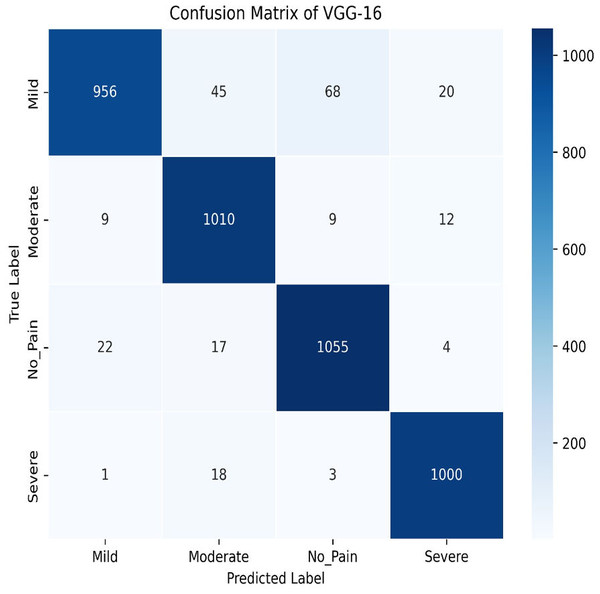

The VGG-16 method is used to evaluate our dataset next. The accuracy plot, as shown in Fig. 19, of VGG-16 shows a steady increase in both training and validation accuracy over 50 epochs. Initially, validation accuracy rises faster than training accuracy but stabilizes around 94.87%, closely following training accuracy, which reaches approximately 93.97%. The minimal gap indicates good generalization, with no significant overfitting observed. The confusion matrix of VGG-16, as shown in Fig. 20, shows strong classification performance across all four categories: Mild, Moderate, No Pain, and Severe Pain. The diagonal values indicate high true positive counts, with minimal misclassifications. Most errors occur between Mild and No Pain, but overall, the model demonstrates excellent accuracy and balanced predictions across classes.

Figure 19: Training and testing accuracy of VGG-16 on the proposed IFEPI dataset.

Figure 20: Confusion matrix among the Mild, Moderate, No_Pain and Severe expressions using the VGG-16 method.

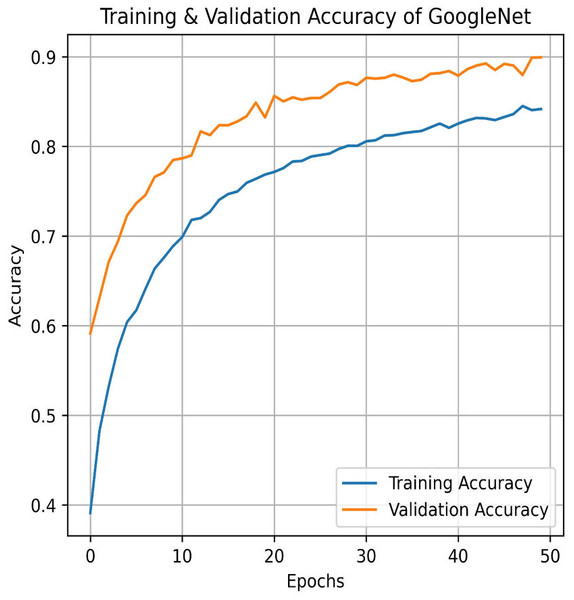

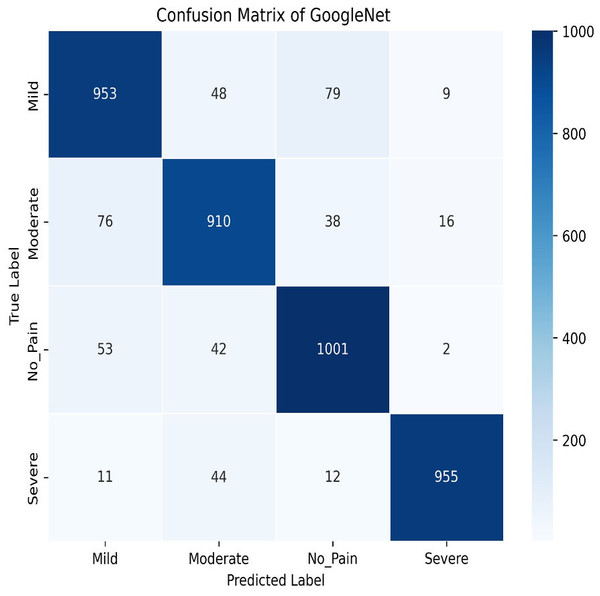

Next, in the evaluation phase, the InceptionV3 (Szegedy et al., 2015) model is used. The learning curve for GoogleNet (InceptionV3) shows promising results, with both training and validation accuracy as steadily increasing over the 50 epochs, as shown in Fig. 21. Training accuracy surpasses 90.01%, while validation accuracy closely follows with 84.91%, indicating effective model generalization. This suggests that InceptionV3 successfully learns the patterns in the dataset without significant overfitting. The confusion matrix in Fig. 22, for GoogleNet (InceptionV3) shows promising classification results. The model demonstrates strong performance in identifying Mild and Severe pain, with most predictions correctly classified. However, there are some misclassifications, particularly between Mild and Moderate Pain as well as No and Severe Pain. Despite these errors, the model performs well, with accurately differentiating between the various pain levels. Overall, GoogleNet achieves a good balance between sensitivity and specificity for each class.

Figure 21: Training and testing accuracy of GoogleNet (InceptionV3) on the proposed IFEPI dataset.

Figure 22: Confusion matrix among the Mild, Moderate, No_Pain and Severe expressions using the GoogleNet (InceptionV3) method.

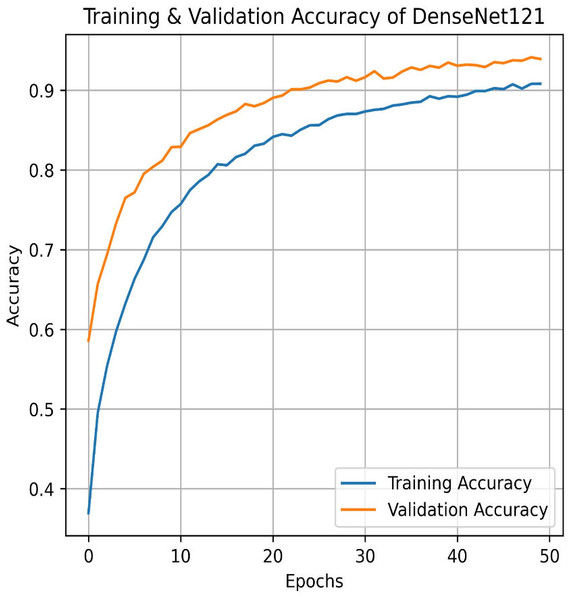

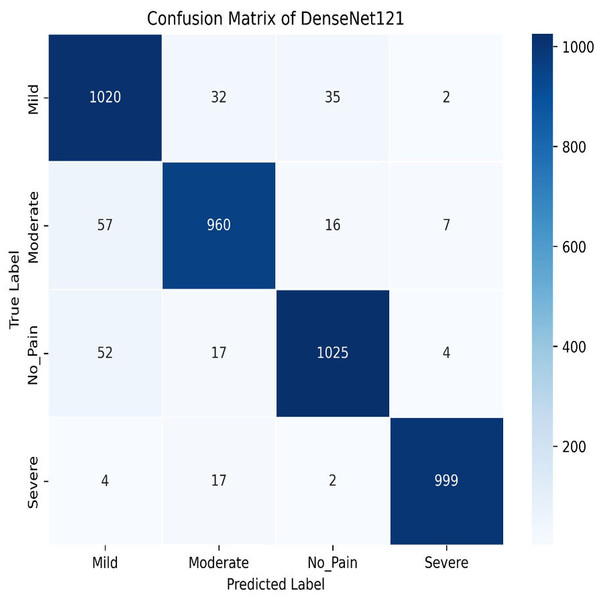

We apply for the DenseNet models i.e., DenseNet121 and DenseNet201. The learning graph of DenseNet121 of Fig. 23 shows impressive performance, with a training accuracy of 90.81% and a validation accuracy of 93.93%. The cross-validation accuracy is 93.97%, indicating strong generalization. The low standard deviation of 0.0041 suggests consistent performance across different validation folds, highlighting the model’s reliability and robustness. The confusion matrix for DenseNet121 illustrates the model’s classification performance across different pain intensity levels: Mild, Moderate, No Pain, and Severe Pain. The matrix shows high true positive values for Mild (1,020) and No Pain (1,025), indicating accurate predictions for these categories. However, there are some misclassifications, particularly between Moderate and Severe Pain, suggesting areas for potential improvement in distinguishing these classes, as shown in Fig. 24.

Figure 23: Training and testing accuracy of DenseNet121 on the proposed IFEPI dataset.

Figure 24: Confusion matrix among the Mild, Moderate, No_Pain and Severe expressions using the DenseNet121 method.

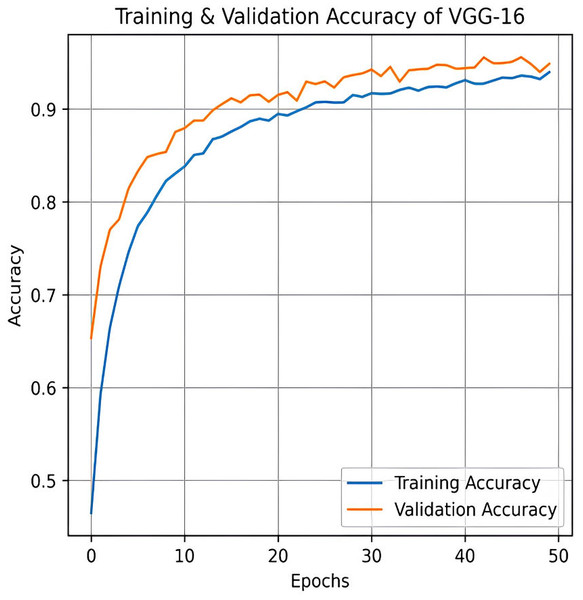

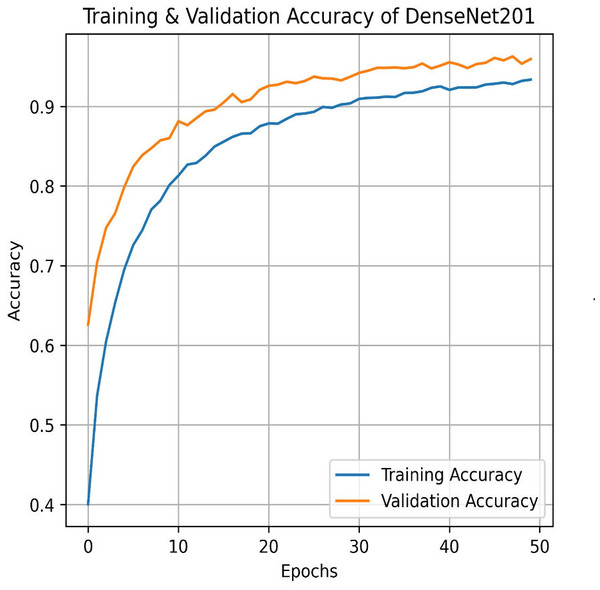

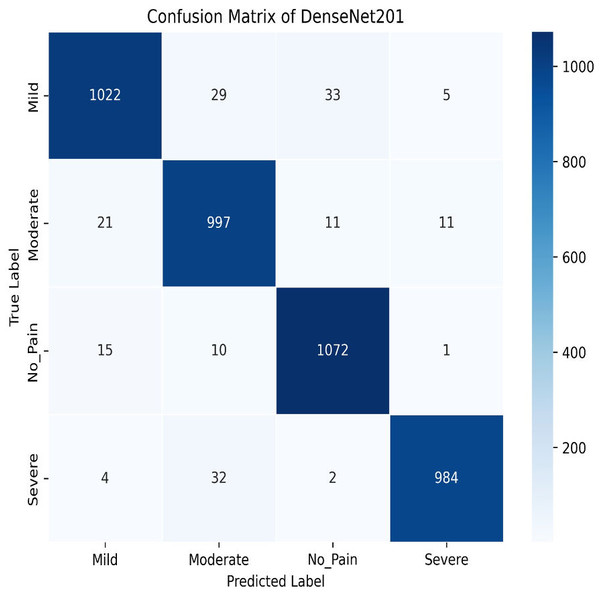

Next, we used the DenseNet201 method. The learning curve shown in Fig. 25 for DenseNet201 shows impressive performance with a training accuracy of 93.37% and a validation accuracy of 95.95%. The cross-validation accuracy is 95.68%, indicating excellent generalization. The low standard deviation of 0.0015 further confirms the model’s stability, making it highly reliable across different datasets and epochs. The confusion matrix for DenseNet201 shows exceptional performance, with a high number of correct classifications across all categories. Mild Pain is accurately predicted with 1,022 correct predictions, while No Pain and Severe Pain also show strong results as shown in Fig. 26. Misclassifications are minimal, with slight confusion between Moderate and Mild classes. The model demonstrates a strong ability to differentiate between pain categories, ensuring reliable predictions across the dataset.

Figure 25: Training and testing accuracy of DenseNet201 on the proposed IFEPI dataset.

Figure 26: Confusion matrix among the Mild, Moderate, No_Pain and Severe expressions using the DenseNet201 method.

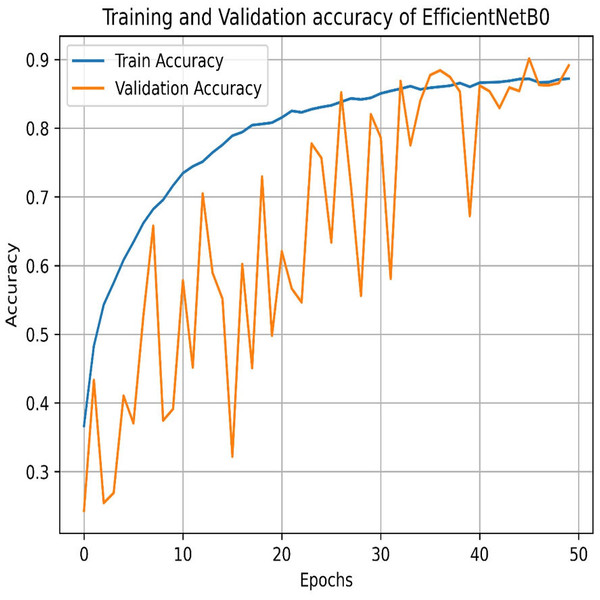

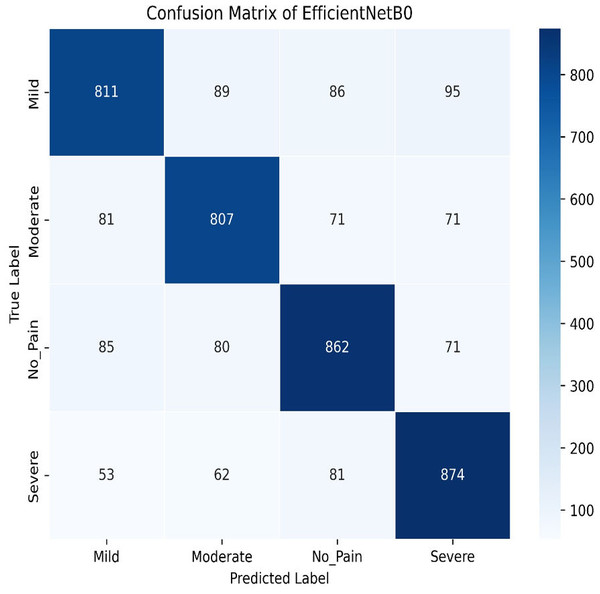

Our experiments end with the deployment of EfficientNet Models. The learning graph of EfficientNetB0, as shown in Fig. 27, demonstrates consistent performance, with a training accuracy of 86.23% and a validation accuracy of 86.61%. The cross-validation accuracy matches the validation accuracy at 86.61%, indicating stable generalization. The standard deviation of 0.0139 reflects minor variability, suggesting reliable and consistent model performance across different validation folds. The confusion matrix, as shown in Fig. 28, of EfficientNetB0 demonstrates its classification performance across four categories: Mild, Moderate, No Pain, and Severe. The model achieves high accuracy, with a strong diagonal dominance indicating correct predictions. Misclassifications are low, suggesting robust generalization. Notably, the No Pain class exhibits the highest correct predictions, while misclassifications are balanced across other categories.

Figure 27: Training and testing accuracy of EfficientNetB0 on the proposed IFEPI dataset.

Figure 28: Confusion matrix among the mild, moderate, no pain and severe expressions using the EfficientNetB0 method.

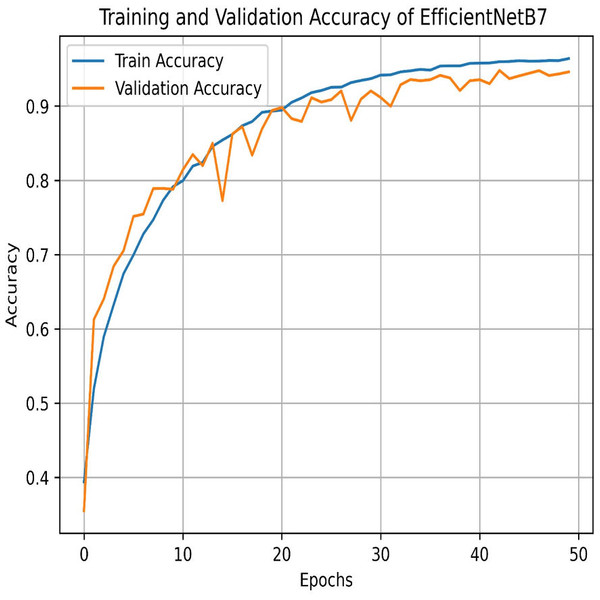

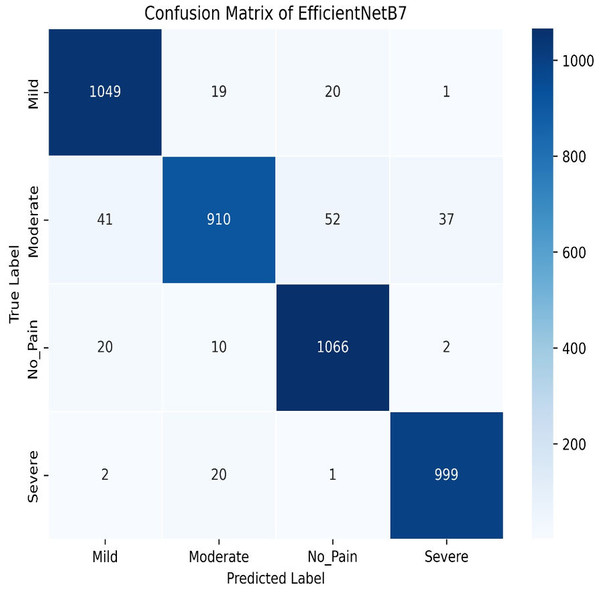

The final method employed for benchmarking our dataset is EfficientNetB7, which outperforms all other models in this study. As illustrated in Fig. 29, EfficientNetB7 achieves a training accuracy of 96.82%, a validation accuracy of 94.61%, a cross-validation accuracy of 93.84%, and a standard deviation of 0.0076, demonstrating its superior performance and reliability. The confusion matrix for the EfficientNetB7 model shows how well it classifies four categories. Mild was predicted correctly 1,049 times, with a few misclassifications as Moderate, No Pain, and Severe Pain. Moderate was mostly predicted 910 times, with some misclassifications such as Mild, No Pain, and Severe Pain. No Pain was predicted correctly 1066 times, with minimal misclassifications. Severe was predicted mostly correctly 999 times, with a few misclassifications as shown in Fig. 30.

Figure 29: Training and testing accuracy of EfficientNetB7 on the proposed IFEPI dataset.

Figure 30: Confusion matrix among the Mild, Moderate, No_Pain and Severe expressions using the EfficientNetB7 method.

In summary, Table 2 presents a comprehensive comparison of various machine learning and deep learning models based on their training accuracy, validation accuracy, mean cross-validation accuracy, and standard deviation of accuracy. Among the baseline models, Random Forest and EfficientNetB7 stand out with the highest training accuracies of 96.91% and 96.82%, respectively. However, Random Forest shows a significant drop in validation accuracy (84.43%) compared to its training accuracy, indicating potential overfitting. In contrast, EfficientNetB7 maintains a high validation accuracy of 94.61%, suggesting better generalization.

| S.No | Model | Training accuracy (%) | Validation accuracy (%) | Mean cross validation accuracy (%) | Standard deviation of accuracies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Logistic Regression | 55.77 | 56.16 | 54.51 | 0.0094 |

| 2 | SVM | 46.04 | 48.06 | 46.17 | 0.0109 |

| 3 | KNN | 80.94 | 79.21 | 76.86 | 0.0086 |

| 4 | Random Forest | 96.91 | 84.43 | 83.06 | 0.0086 |

| 5 | LeNet | 86.95 | 84.87 | 86.53 | 0.0094 |

| 6 | AlexNet | 92.70 | 90.73 | 89.89 | 0.0219 |

| 7 | VGG-16 | 93.97 | 94.87 | 94.52 | 0.0079 |

| 8 | GoogleNet (InceptionV3) | 90.01 | 84.91 | 89.08 | 0.0109 |

| 9 | DenseNet121 | 90.81 | 93.63 | 93.17 | 0.0041 |

| 10 | DenseNet201 | 93.37 | 94.95 | 93.68 | 0.0015 |

| 11 | EfficientNetB0 | 86.23 | 86.61 | 86.61 | 0.0139 |

| 12 | EfficientNetB7 | 96.82 | 94.61 | 93.84 | 0.0076 |

Deep learning models, particularly VGG-16 and DenseNet201, demonstrate strong performance with validation accuracies of 94.87% and 94.95%, respectively. Both models also exhibit high mean cross-validation accuracies (94.52% for VGG-16 and 93.68% for DenseNet201) and low standard deviations, indicating consistent performance across different folds. AlexNet and GoogleNet (InceptionV3) also perform well, with validation accuracies above 90%, though GoogleNet shows a slightly larger drop between training and validation accuracy, hinting at minor overfitting.

Among simpler models, KNN achieves a high training accuracy of 80.94% but suffers from a noticeable drop in validation accuracy (79.21%) and mean cross-validation accuracy (76.86%), suggesting limited generalization. Logistic Regression and SVM perform poorly, with validation accuracies of 56.16% and 48.06%, respectively, indicating they may not be well-suited for the complexity of the task.

In summary, deep learning models, especially VGG-16 and DenseNet201, outperform traditional machine learning models in terms of both accuracy and consistency. EfficientNetB7 also shows robust performance, making it a strong contender. However, simpler models like KNN, Logistic Regression, and SVM struggle to generalize effectively, highlighting the importance of model complexity for this task.

During the experiments, it was observed that models that extract minor features from the images, such as DenseNet201 and EfficientNetB7, improved the misclassification, especially in Mild and Moderate Pain classes. However, there is still some misclassification, and it could be, firstly, due to the facial expressions of Mild and Moderate pain may share common features, making it difficult for the model to distinguish them reliably, and secondly, as labeling is done manually, there may be some subjectivity in distinguishing between similar intensity levels because Fleiss’ Kappa focuses on reliability, and not validity.

Conclusions

During the neonatal video collection process, we concurrently capture not only facial expression data but also pain-related sound and body gesture data. The recorded videos are obtained within authentic vaccination room settings, resulting in complex and unclear voice data. This data encompasses various sounds, including the pain cries of multiple infants and the voices of medical professionals. This audio information undergoes cleaning and preprocessing to enhance clarity and usability in subsequent pain evaluation steps. Additionally, the real vaccination environment introduces complexities such as occlusions, as illustrated in Fig. 3, where body parts, clothing, and medical instruments may obstruct the view. Consequently, the body gesture data requires cleaning and preprocessing to address these occlusions and can then be utilized in conjunction with sound data for the subsequent evaluation of infants’ pain. This paper introduces a pioneering dataset named Infants’ Facial Expressions Pain Intensity (IFEPI) designed for the recognition of infants’ pain through facial expressions. The IFEPI dataset comprises a total of 25,000 facial expression images collected from 120 Pashtun infants across two distinct vaccination centers located in Peshawar, the capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, affiliated with the Federal Directorate of Immunization Pakistan and WHO Pakistan. The dataset encompasses four emotion categories: No Pain, Mild Pain, Moderate Pain, and Severe Pain, with each category comprising 6,250 image samples.

The primary contribution of this study lies in the establishment of a substantial facial expression dataset specifically for infants’ pain. In comparison to existing datasets for neonatal pain facial expressions, the IFEPI dataset exhibits four distinctive advantages or characteristics. Firstly, it is larger than the current neonatal pain facial expression datasets. Secondly, it includes four different degrees of pain data (No Pain, Mild Pain, Moderate Pain and Severe Pain), a feature lacking in other existing datasets. Thirdly, the IFEPI dataset is based on Pashtun Infants, in contrast to Caucasian-based datasets for neonatal pain facial expressions. Lastly, expressions in the dataset are 100 percent spontaneous pain expressions.

Unlike previous studies that used small datasets, the proposed work utilizes a large and diverse dataset, significantly enhancing the accuracy and reliability of the model. Exposing the model to a variety of facial expressions improves generalization and better represents real-world scenarios. Additionally, while prior research often focused on binary classification of facial expressions (pain vs no pain), this study introduces a four-level classification, providing a more detailed and precise assessment of pain intensity. This advancement enables more accurate pain detection, resulting in improved clinical decisions. Furthermore, the proposed work emphasizes real-time facial expression analysis, which is crucial for practical applications in settings such as hospitals or neonatal care units, where quick pain assessment is vital. Unlike earlier studies that focused on narrower age ranges, this research work covers a broader range, and including infants aged 2 to 12 months. This broader age coverage makes the findings more applicable and generalizable across diverse infant populations, addressing a significant gap in previous research. Overall, the proposed study enhances pain detection models, offering both more precise and broader applicability, which can significantly benefit clinical practices in various real-world environments.