Dental caries risk assessment using caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA) tool in Yanbu city, Saudi Arabia—a cross sectional study

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Amjad Abu Hasna

- Subject Areas

- Dentistry, Epidemiology, Public Health

- Keywords

- Dental caries, Risk assessment, Disease indicators, Management, Prevention

- Copyright

- © 2026 Albishi et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Dental caries risk assessment using caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA) tool in Yanbu city, Saudi Arabia—a cross sectional study. PeerJ 14:e20540 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20540

Abstract

Introduction

Dental caries affects billions of people globally with complications leading to a reduced quality of life. Investigating dental caries risk factors is of the utmost importance to prevent future carious lesions. To date, most oral health research focused on measuring the prevalence of the disease at the expense of investigating the caries risk. This study aims to establish a baseline record on the level of dental caries risk in Yanbu city and to explore the factors associated with an increased risk in permanent dentition.

Methods

Contact information was obtained from all Ministry of Health facilities across Yanbu city. Participants aged ≥18 years with permanent dentition were included via simple random sampling. Clinical examinations were conducted to collect potential risk and protective factors using CAMBRA tool. In addition, other factors including demographic characteristics, dental attendance, smoking history, dental anxiety, and the presence of comorbidities, were collected. Descriptive, chi2 test, and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to determine major potential risk factors and the level of caries risk.

Results

A total of 141 participants were included in the study. The most prevalent risk factor was the presence of heavy plaque (51.1%), 97.2% of the participants presented with cavitated teeth. Factors such as the use of fluoridated toothpaste once/twice daily and a chlorhexidine gluconate mouth rinse were associated with a decreased risk of caries (p-value < 0.05). Conversely, frequent snacking, medications-induced hyposalivation, the presence of heavy plaque, deep pits and fissures, exposed tooth roots, white spot lesions, new non-cavitated lesions in enamel and existing restorations were associated with an increased risk for dental caries (p-value < 0.05).

Conclusion

This study represents a foundational assessment of caries risk via the CAMBRA protocol among an underreported population in Saudi Arabia. This work addresses a critical gap and highlights important key factors that can be utilized in managing dental caries clinically and in the implementation of larger-scale caries preventive programs in the region.

Introduction

Dental caries affects billions of people worldwide and contributes to poor oral health. According to a recent publication by the Global Burden of Diseases, the reported global prevalence of untreated dental caries was 27.5% and increased by 53% between 1990 and 2021. Despite being largely preventable, the number of new cases of untreated caries in permanent teeth reached 2.37 billion (Bernabe et al., 2025; Alves-Costa, Romandini & Nascimento, 2025). Furthermore, according to a recent systematic review conducted in Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of dental caries in permanent dentition from eight city locations ranged from 5% to 99%. Although no study has been conducted in Yanbu city, Jeddah alone (part of the western region) reached a prevalence of 99% (Alshammari et al., 2021). Moreover, the estimated worldwide expenditure due to dental diseases reached $544.41 billion in 2015, with an expenditure of $7.78 billion in North Africa and the Middle East (Righolt et al., 2018). A recent publication by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019 on the economic impact of oral diseases in Saudi Arabia reported that the total expenditure on dental healthcare reached 1,252 million US dollars. Moreover, the total productivity losses due to five oral diseases reached 2,016 million US dollars (World Health Organization, 2022).

Many factors play a role in the progression of dental caries, such as acid-producing bacteria, fermentable carbohydrates, and abnormalities in saliva production. While such factors help demineralize and further destroy the tooth structure, other factors have a protective effect on carious lesions and help promote the remineralization of the tooth. These include having a normal salivary flow, antibacterial agents, calcium, phosphate, and fluoride availability for remineralization (Pitts et al., 2017; Featherstone & Chaffee, 2018). However, pathological factors and net demineralization over a sufficient amount of time can lead to the development of cavitations. Complications of untreated dental caries, such as pulp exposure and destroyed tooth structure, can eventually lead to a reduction in quality of life. It can be costly and debilitating to perform daily tasks such as speaking, eating (inefficient mastication), and poor sleeping from dental pain (Eid, Khattab & Elheeny, 2020; Monse et al., 2010).

Investigating the determinants of caries risk is paramount to successfully manage and prevent future occurrences of dental caries lesions (Featherstone et al., 2021). This can be accomplished by using a tool called Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA), which is an extensively studied tool among thousands of patients and has been shown to be highly predictive of future caries among those aged 6 through adulthood. Additionally, this tool can be helpful in observing the population at risk for dental caries. A study carried out in Sakaka, Saudi Arabia using the CAMBRA tool, revealed that being older and a rural resident were among the high dental caries risk groups (Iqbal et al., 2022). This tool helps dentists measure the protective factors that aid in remineralization and assess the risks that lead patients to develop dental caries. Promoting protective factors and mitigating risks can help prevent and reduce the risk of dental caries (Featherstone et al., 2019; Rechmann et al., 2018). To date, most oral health research conducted in Saudi Arabia focused on measuring the prevalence of the disease at the expense of measuring the caries risk level especially on semi-urban communities like Yanbu. Furthermore, previous studies investigating caries risk have often recruited participants from dental departments, while such setting provide access to clinical populations, they may inadvertently bias the results by overrepresenting individuals already at high risk for dental diseases. This study is the first to offer a detailed snapshot of caries risk in an understudied population with the aim of answering two research questions: (1) What is the level of caries risk among adults (≥ 18 years) with permanent dentition in Yanbu city? and (2) Which potential factors are associated with the level of caries risk in this same population?

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 10 different healthcare clinics across Yanbu city for sampling. This covered all Ministry of Health (MoH) establishments; each provided a list of patients’ contact details, both in-patients and out-patients lists were obtained. Simple random sampling was adopted, and a computer number generator randomly selected participants from each facility’s patient list. The data collection and clinical examination were conducted at MoH’s primary health care facilities in Yanbu city from June to December 2024. The inclusion criteria included presenting with permanent teeth and participants aged ≥ 18 years. Pregnant women, edentulous participants, those with incomplete or missing data, and those who refused clinical examination were excluded from the study. Ethical approval was granted from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the General Directorate of Health Affairs in Madinah, Ministry of Health with approval number: 24-035, and the research was carried out after voluntary participation and a written informed consent from all the participants were obtained. The research team explained the study objectives and purposes to all the participants thoroughly. A confirmation text with a detailed study objective and what to expect on the day of the interview/examination was sent to increase the response rate and address selection bias. The participants were allowed to ask any questions related to the study and research for clarity before and during the study and clinical examination. Moreover, text messages or a phone call a day before and on the day of examination were sent as reminders. Interviews and clinical examinations were collected via a data extraction form. The data collection form was written in English and was filled out by the examiner only. To account for recall bias with some question items, such as medication use, toothpaste fluoridation and mouth rinse, we asked the participants to bring their daily medications, toothpastes and mouth rinses. In accordance with the WHO oral survey guidelines, the clinical examination used a blunt CPI probe and mouth mirrors. Because the data collection and all clinical examinations were performed by a single dentist (the primary investigator of the research), the assessment of inter-rater reliability was not needed. Data collection was done at any available MoH dental clinics in Yanbu city. Our main exposure is potential risk factors that can predict the risk of caries.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) was followed in reporting, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on the use of human subjects in research (edition 2013) (Vandenbroucke et al., 2020; World Medical Association, 1974).

Data and collection tools

Data such as age, sex, nationality, marital status, place of residence, educational level, and monthly income were collected. In addition, dental visit history, presence of comorbidities, smoking history, insurance coverage and presence of dental anxiety were also collected as independent variables/exposure. A validated caries risk assessment tool, the Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA), was used to identify the level of caries risk in the study population. The level of caries risk was our dependent variable/outcome (Featherstone et al., 2021; Featherstone et al., 2019; Rechmann et al., 2018). CAMBRA measures the following: protective factors, biological or environmental risk factors (biological and environmental risk factors are split into (a) question items, (b) clinical exams), and disease indicators. The score is calculated and classified as follows: low = −8 to −2; moderate = −1 to +2; high = +3 to +17; extreme = +18 to +30, and/or is a high-risk level plus measured or observed hyposalivation.

The salivary flow rate was measured via the stimulated whole saliva (SWS) flow. The normal stimulated salivary flow rate is between 0.2 and 7.0 mL/min, with an average rate between 1.5 and 2.0 mL/min. Hyposalivation was considered when the rate was <0.5–0.7 mL/min for stimulated whole saliva. It was carried out using sugar-free lemon candy as recommended (Hu et al., 2021; Navazesh & Kumar, 2008; Villa, Connell & Abati, 2014).

Sample size and sampling technique

The sample size calculation was based on the formula described in previous literature (Charan & Biswas, 2013): n = for cross-sectional studies. where n = sample size, Z = Z statistic for a level of confidence (1.96 for 95% confidence level), P = expected prevalence or proportion, and d = precision. Previous studies conducted in Saudi Arabia have shown that 85% of patients are in the high-risk category for dental caries according to the CAMBRA assessment, whereas 15% are in the moderate risk group. Although conducted in a different region in the Kingdom, their findings provided sufficient foundation to proceed without a pilot study in this population (Iqbal et al., 2022). With 80% power, α = 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval, this yields a sample size of 196 for dental caries risk.

Statistical methods

Where applicable, categorical variables were compared via Fisher’s exact and the Pearson chi-square (X)2 test. Descriptive analysis was used for the percentage, mean, and standard deviation (S.D). To find an association between the indicators and dental caries risk, univariable and multivariable linear regression analyses were used, and the results are presented as the beta coefficient (β) with standard error (SE), p-value (significance level <0.05), and 95% confidence interval. The variables included in the multivariable analysis were based on the univariable analysis with a p-value (<0.05) and previous findings and clinical importance. Potential confounders (age, nationality and monthly income) were investigated by using the bivariate analysis as factors associated with both the exposure and the outcome, but not in the causal pathway. These factors were adjusted for in the final regression model to ensure more accurate estimation of the associations between the outcome variable (dental caries risk level) with the exposure variables (risk and protective factors). To find the best fitting model, a stepwise selection procedure was employed. We assessed multicollinearity among covariates via the variance inflation factor (VIF), and all the VIFs of the independent variables were <4 (Menard, 2002). As our dataset was complete except for two variables with missing values in marital status and smoking history, these variables were only used for the descriptive analysis and statistical imputation was not considered necessary. A chi-square (X)2 or Fisher’s exact test was also used to measure the difference between possible risk factors and caries risk as a categorical variable (moderate and high) in a supplementary file. A two-sided α of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS package v.22.

Results

Participants’ demographics and background information

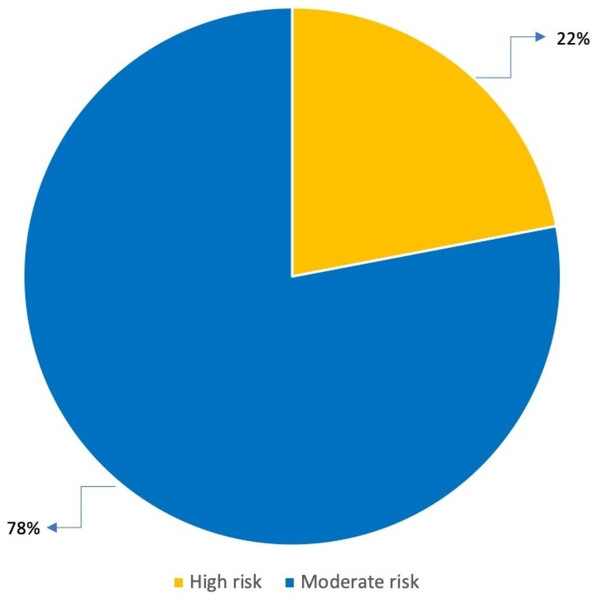

The descriptive analysis data of our study sample are presented in Table 1. A total of 141 participants were enrolled (response rate: 17.5%), with a mean age of 37.9 ± 11.47 years. The majority were male (53.9%), Saudi (86.5%), and married (72.9%). Comorbidities were observed in 31.9% of our participants, 79.4% were nonsmokers and none reported recreational drug use. Over half (57.5%) held a bachelor’s degree, and only 22.7% had insurance coverage. Nearly half of the participants (49.7%) had not visited a dentist in over 6 months, and 66.7% did not report having dental anxiety. Most had normal salivary flow (97.2%), with a mean salivary flow rate/minute of 2.2 ± 0.79. Based on risk stratification, 78% were at moderate and 22% at high risk for dental caries (Fig. 1).

| Variable | Category | n (%) | CAMBRA Mean ± SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 76 (53.9) | 1.09 ± 1.89 | ||

| Female | 65 (46.1) | 0.95 ± 1.72 | |||

| Nationality | Saudi | 122 (86.5) | 1.13 ± 1.8 | ||

| Non-Saudi | 19 (13.5) | 0.11 ± 1.61 | |||

| Residence | Rural | 2 (1.4) | 2.0 ± 2.82 | ||

| Urban | 139 (98.6) | 0.99 ± 1.8 | |||

| Marital status | Single | 29 (20.6) | 1.55 ± 1.48 | ||

| Married | 100 (70.9) | 0.87 ± 1.85 | |||

| Divorce | 6 (4.3) | 0.83 ± 2.48 | |||

| Widow | 2 (1.4) | 0.0 ± 1.41 | |||

| Education level | No education | 2 (1.4) | 0.0 ± 1.41 | ||

| Primary education | 11 (7.8) | 0.55 ± 1.92 | |||

| Secondary education | 44 (31.2) | 1.0 ± 1.89 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 81 (57.4) | 1.10 ± 1.78 | |||

| Post-graduate | 3 (2.1) | 0.67 ± 1.53 | |||

| Frequency of dental visit | Never | 5 (3.5) | −1.20 ± 0.45 | ||

| ≤ 6 months | 66 (46.8) | 1.26 ± 1.79 | |||

| >6 months | 70 (49.6) | 0.97 ± 1.78 | |||

| Dental anxiety | No | 94 (66.7) | 0.86 ± 1.81 | ||

| Yes | 47 (33.3) | 1.36 ± 1.77 | |||

| Smoking status** | Nonsmoker | 112 (79.4) | 0.89 ± 1.78 | ||

| Smoker | 27 (19.1) | 1.56 ± 1.93 | |||

| Comorbidity | Present | 45 (31.9) | 0.80 ± 1.89 | ||

| Absent | 96 (68.1) | 1.13 ± 1.79 | |||

| Medical insurance | No | 109 (77.3) | 1.00 ± 1.83 | ||

| Yes | 32 (22.7) | 1.13 ± 1.77 | |||

| Continuous Variables | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Age (years) | 37.90 ± 11.5 | ||||

| Monthly income (SAR) | 5,598.99 ± 5,819.5 | ||||

| Salivary flow rate mL/min | 2.16 ± 0.79 | ||||

Notes:

- SAR

-

Saudi Riyals

Figure 1: Proportion of participants with caries risk levels.

This figure shows the proportion of participants with moderate and high caries risk levels. The majority of the participants had a moderate risk for dental caries (78%), whereas approximately 22% had a high caries risk.Caries risk assessment

Table 2 shows the distribution of our study participants with CAMBRA protective, biological, and disease indicators. The most prevalent risk factor was the presence of heavy plaque on teeth (51.1%). Dental caries affected 97.2% of the participants, 49.6% had white spot lesions and 67% had existing restorations. Most participants brushed at least once daily with fluoridated toothpaste (76.6%) but none had received fluoride varnish therapy in the past 6 months.

| CAMBRA question items | Yes n (%) |

No n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Protective factor | ||

| Fluoridated water | 141 (100) | 0 (0) |

| F toothpaste at least once a day | 108 (76.6) | 33 (23.4) |

| F toothpaste 2X daily or more | 62 (44.0) | 79 (56.0) |

| 5,000 ppm F toothpaste | 0 (0) | 141 (100) |

| F varnish last 6 months | 0 (0) | 141 (100) |

| 0.05% sodium fluoride mouthrinse daily | 7 (5.0) | 134 (95.0) |

| 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthlines daily 7 days monthly | 3 (2.1) | 138 (97.9) |

| Normal salivary function | 137 (97.16) | 4 (2.84) |

| Biological or environmental risk factors | ||

| Frequent snacking (>3 times per day) | 51 (36.2) | 90 (63.8) |

| Hyposalivatory medications (medications-induced hyposalivation) |

14 (9.9) | 127 (90.1) |

| Recreational drug use | 0 (0) | 141 (100) |

| Biological risk factor—clinical exam | ||

| Heavy plaque on the teeth | 72 (51.1) | 69 (48.9) |

| Reduced salivary function (low flow rate) | 7 (5.0) | 134 (7.0) |

| Deep pits and fissures | 35 (24.8) | 106 (75.2) |

| Exposed tooth roots | 54 (38.3) | 87 (61.7) |

| Orthodontic appliances | 8 (5.7) | 133 (94.3) |

| Disease indicators | ||

| New cavities or lesion(s) into dentin | 137 (97.2) | 4 (2.8) |

| New white spot lesions on smooth surfaces | 70 (49.6) | 71 (50.4) |

| New non-cavitated lesion(s) in enamel | 65 (46.1) | 76 (53.9) |

| Existing restorations in last 3 years (new patient) or the last year (patient of record) | 95 (67.4) | 46 (32.6) |

Associations between potential factors and caries risk assessment

The predictor variables that have a significant association with dental caries risk are presented in Table 3 using a univariable and multivariable regression analyses. In the multivariate analysis, daily use of fluoridated toothpaste and 0.12% chlorhexidine mouth rinses were significantly protective against dental caries (p < 0.05). However, frequent snacking (>3 times/day) and medications-induced hyposalivation increased caries risk (β = 0.89, 1.09; p < 0.05). Additional risk factors that increased caries risk included heavy plaque, deep pits and fissures, exposed roots, white spot lesions and having existing restorations (p < 0.05).

| Variables | Univariable regression | Multivariable regression*** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | p-value | Beta coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | p-value | |

| F toothpaste at least once a daily | −0.17 (0.33) | −2.36 to −1.05 | 0.00* | −0.81 (0.12) | −1.06 to −0.57 | 0.00* |

| F toothpaste 2X daily or more | −1.40 (0.28) | −1.96 to −0.84 | 0.00* | −1.06 (0.10) | −1.27 to −0.85 | 0.00* |

| 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinse daily 7 days monthly | −2.07 (1.04) | −4.14 to −0.01 | 0.49* | −0.99 (0.31) | −1.61 to −0.36 | 0.00* |

| Frequent snacking (>3 times per day) | 1.18 (0.30) | 0.58 to 1.78 | 0.00* | 0.89 (0.09) | 0.71 to 1.08 | 0.00* |

| Medications-induced hyposalivation | 1.47 (0.49) | 0.49 to 2.45 | 0.00* | 1.09 (0.16) | 0.77 to 1.39 | 0.00* |

| Heavy plaque on the teeth | 1.64 (0.27) | 1.11 to 2.18 | 0.00* | 0.88 (0.09) | 0.69 to 1.07 | 0.00* |

| Deep pits and fissures | 1.18 (0.34) | 0.51 to 1.85 | 0.00* | 0.82 (0.11) | 0.61 to 1.04 | 0.00* |

| Exposed tooth roots | 1.03 (0.30) | 0.44 to 1.63 | 0.00* | 0.91 (0.10) | 0.71 to 1.11 | 0.00* |

| Orthodontic appliances | 1.42 (0.65) | 0.14 to 2.71 | 0.03* | 0.38 (0.19) | −0.01 to 0.76 | 0.06 |

| New white spot lesions on smooth surfaces | 2.07 (0.25) | 1.58 to 2.57 | 0.00* | 1.16 (0.12) | 0.92 to 1.40 | 0.00* |

| New non-cavitated lesion(s) in enamel | 1.80 (0.27) | 1.28 to 2.33 | 0.00* | 0.96 (0.12) | 0.73 to 1.19 | 0.00* |

| Existing restorations in last 3 years (new patient) or the last year (patient of record) | −0.82 (0.32) | 0.19 to 1.45 | 0.01* | 1.01 (0.10) | 0.81 to 1.21 | 0.00* |

Discussion

In this study, the majority of participants had a moderate risk for dental caries (78%), which is relatively close to findings reported by Alonazi et al. (2024) and Iqbal et al. (2024) where 66% and 62.2% of their participants, respectively were in the moderate risk category. However, our population demonstrated a lower risk than that reported in another study conducted in Sakaka, Saudi Arabia. This difference may be explained by the fact that less than half of their participants had water fluoridation and presented with higher plaque levels, both of which can increase caries risk. Moreover, nearly all environmental and disease indicators, except new cavities or lesions into dentin, were significantly associated with an increased risk for dental caries, in consistent with earlier findings by Iqbal et al. (2022), Iqbal et al. (2024) and Alonazi et al. (2024). Although all participants reported having access to fluoridated water, this has not appeared to decrease the burden or risk for dental caries; almost 97% of the population presented with a carious lesion, and two-thirds had received prior restorative treatments. Similar findings were previously observed by Iqbal et al. (2022) and Featherstone & Chaffee (2018) where participants remained at a high caries risk level despite both topical and water fluoridation. A possible reason for this can be explained in an earlier observation by Featherstone (2000) where he emphasized the importance of adding antibacterial therapy along with topical and water fluoridation to reduce the bacterial challenge and sufficiently reduce caries risk. Notably, we found participants who used antibacterial agents such as chlorhexidine had a significant reduction in caries risk.

Socioeconomic factors had a role in caries risk levels. About 77% of the participants were uninsured, which may reflect the increased levels in caries risk among the study population. Besides, a previous study reported 70% of individuals with fair or poor health lacked a private dental insurance, and almost 35% of them had untreated dental caries (Wei et al., 2022). Lack of dental insurance limits the access to dental care and can therefore exacerbate oral health disparity. While over two-thirds of the participants reported using fluoridated toothpaste daily, heavy plaque was observed in more than half of the study participants with an increased caries risk. These findings are consistent with those reported by Alonazi et al. (2024) among the Saudi population, and may indicate inadequate knowledge regarding proper oral hygiene practices. Ten percent of the participants were using medications that induce hyposalivation such as antihistamines. They can cause hyposalivation and increases the risk for dental caries. While we observed a significant association between a reduced salivary flow and increased caries risk, these contrast with findings observed by Iqbal et al. (2024), where the association was not significant. Reduced salivation from medications can be overlooked by healthcare providers, but if managed hand in hand with a dental professional, can help reduce the risk of dental caries (Einhorn, Georgiou & Tompa, 2020).

The beneficial effect of saliva in the oral cavity is well established (Mandel, 1989). Briefly, it maintains a neutral pH in the mouth and helps clear sugars and carbohydrates. A recent review reported inconclusive results when hyposalivation and increased dental caries were assessed among children and adolescents (Dos Santos Letieri et al., 2022). However, other studies, although conducted on adolescents and older adults, have shown a similar trend to our study: hyposalivation was associated with increased caries (Hayes et al., 2016). Presenting with exposed roots had a significantly higher risk for dental caries. This supports findings from previous literature that demonstrate a significant association between root exposure and dental caries. This can be explained by the higher critical pH for root dentin demineralization than enamel, which makes root surfaces more prone to dental caries. However, Iqbal et al. (2024) found this association to be insignificant (Shetty, Hegde & D’Souza, 2024). None of the participants reported recreational drug use; this finding may be biased by the social pressure and the stigma associated with recreational drug use and thus may not reflect the true relationship (Yang et al., 2017). Many of the participants had white spot lesions and frequent snacking with a lack of fluoride varnishes, which increases their risk for dental caries. These findings were consistent with previous studies among the Saudi population conducted by Iqbal et al. (2022) and Alonazi et al. (2024) emphasizing a lack of utilization of fluoridated therapy as a preventive measure for dental caries. This study faced some limitations, a low response rate led to a reduced sample size and may have introduced selection bias. This could have limited the statistical power and obscured the true associations. Measures were taken to address this issue and increase the response rate early in the study design, but unfortunately, few studies have been conducted in Yanbu, and there was some fear around the idea of research participation. Second, this study was subjected to recall bias, which could have under- or overestimated the observed associations. Although multiple attempts were made to control for this, such as asking participants to bring their toothpastes, mouth rinses and medications, we cannot deny that some question items from the CAMBRA tool depended on the memory of the participants, such as frequent snacking and the use of fluoride varnish in the past six months. Third, drug use and smoking history are stigmatized socially and may be underreported, not reflecting the true association. Finally, it was performed in MoH clinics only, which may decrease the generalizability of the outcome. Despite these limitations, the study presented key strengths. The use of the validated CAMBRA protocol in an understudied population offers data on multiple risk and protective factors, such as plaque levels, drug-induced hyposalivation and fluoridation. This enables a comprehensive assessment of caries risk levels. These findings can help in the initiation of oral health campaigns that focus on risk factors associated with dental caries and promote protective behaviors. Assessing the caries risk profile for every patient may often be overlooked in dental practice. However, we highly recommend implementing this comprehensive strategy, as it can potentially reduce the burden of dental caries if the risks are managed early by emphasizing the protective factors and mitigating caries-related risk factors (Kriegler & Blue, 2021).

Conclusion

Despite the limitation, this study represents a foundational assessment of caries risk via the CAMBRA protocol in a population largely underrepresented in the Saudi dental literature. It addresses the overrepresentation bias observed in previously conducted studies in the region. There is a scarcity of regional and national data on caries risk factors particularly with regard to using salivary tests within the CAMBRA framework. By addressing this gap, this study offers key insights that support the integration of risk-based caries management into the clinical practice and dental policy. These findings can also aid in the implementation of a larger scale caries preventive programs in the region.

Supplemental Information

A chi-square (X) 2 or Fisher’s exact test used to measure the difference between possible risk factors and caries risk as a categorical variable (moderate and high)

*p-value ¡ 0.05.