Evaluation of the Cleveland Clinic Score for predicting acute kidney injury across different elective cardiac surgeries—a retrospective study

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Faiza Farhan

- Subject Areas

- Cardiology, Internal Medicine, Nephrology

- Keywords

- Acute kidney injury, Cardiac surgery, Cleveland clinic score, Acute kidney injury prediction model

- Copyright

- © 2026 Koziołet al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Evaluation of the Cleveland Clinic Score for predicting acute kidney injury across different elective cardiac surgeries—a retrospective study. PeerJ 14:e20533 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20533

Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) after cardiac surgery is a serious postoperative complication associated with an increased risk of mortality. The Cleveland Clinic Score (CCS) is one of the tools that allows preoperative assessment of the likelihood of developing AKI. However, the tool has not been validated in different types of cardiac surgery procedures. Our aim was to evaluate the CCS before different types of cardiac surgery and to assess the usefulness of this tool as a predictor of AKI.

Methods

In this retrospective study we included patients who underwent elective cardiac surgery in 2023. Our endpoint was AKI, as defined by the Kidney Diseases Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. The predictive value for AKI after cardiac surgery (CCS) was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) values.

Results

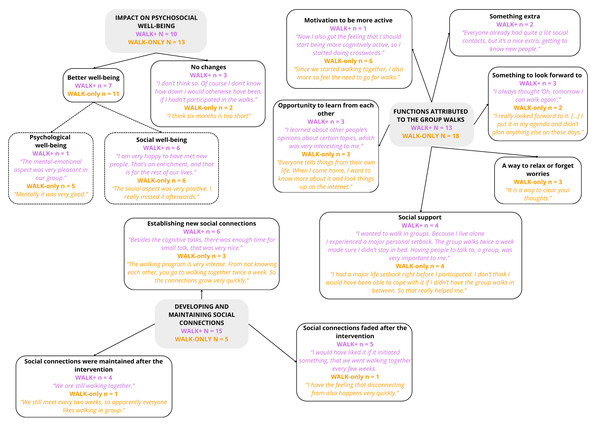

A total of 610 patients underwent elective cardiac surgery. Patients with and without AKI were divided into CCS stages: stage I (57.8 vs 72.3%), stage II (36.1 vs 26.1%), stage III (5.4 vs 1.6%), stage IV (0.6 vs 0%). The AUC for all operations was 0.630 (95% CI [0.580–0.679], p < 0.001), stage I 0.428 (95% CI [0.376–0.480]; p = 0.006), stage II 0.550 (95% CI [0.498–0.602]; p = 0.057) and for stage III 0.519 (95% CI [0.467–0.572]; p = 0.464). The AUC values were significant only for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) 0.650 (95% CI [0.552–0.748]) and aortic valve replacement/plasty (AVR/AVP) 0.629 (95% CI [0.550–0.709]).

Conclusions

The overall CCS value showed a moderate predictive ability for AKI (AUC 0.630) and particularly useful for predicting renal replacement therapy (RRT), but for individual groups the scale should be modified by adding several new factors.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a serious complication that can occur after cardiac surgery. Depending on the author and definition used, 5–30% of cardiac surgery patients may develop AKI. Exposure to nephrotoxic drugs and substances, such as aminoglycosides and radiocontrast agents, may increase the risk of developing AKI (Chertow et al., 1997; Rosner & Okusa, 2006; Huen & Parikh, 2012; Bhat et al., 1976; Gailunas et al., 1980; Corwin et al., 1989). The reported pathophysiological mechanisms for AKI caused by cardiac surgery include ischemic injury, renal reperfusion syndrome, inflammation, atheroembolism, neurohormonal activation, and oxidative stress (Sethi et al., 1987; Perella et al., 1992; Wan, LeClere & Vincent, 1997; Doty et al., 2003). The risk of mortality associated with AKI after open heart surgery is 5 times higher in patients with AKI than in patients without AKI (Thakar et al., 2007; Rao et al., 2018; Korczak et al., 2022).

The use of less invasive cardiac surgical techniques and off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting has resulted in lower mortality rates and incidences of acute renal failure among patients undergoing minimally invasive and/or off-pump surgery. However, post-operative renal dysfunction has remained unchanged in conservative open-heart surgery. After cardiac surgery, one to five percent of patients require dialysis for AKI, and this condition is strongly associated with perioperative morbidity and mortality (Zhang et al., 2008; Swaminathan et al., 2007). The mortality rate of patients with AKI requiring dialysis is estimated to be greater than 50% (Lopez-Delgado et al., 2013). AKI associated with cardiac surgery increases the risk of infection and prolongs hospital and intensive care unit stays (Bove et al., 2004; Lassnigg et al., 2004). This increases the use of healthcare resources and is associated with higher mortality (Ryckwart et al., 2002).

Several risk models have been developed to estimate the risk of postoperative kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Among these models, the Cleveland Clinic model is the most widely tested, and according to several studies, it has the highest discriminative power in most populations tested (Huen & Parikh, 2012; Englberger et al., 2010). The Cleveland Clinic Score (CCS), developed by Thakar et al. (2005), is a clinical tool to predict AKI risk after cardiac surgery, incorporating factors such as female gender, congestive heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <35%, preoperative intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) use, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), insulin-dependent diabetes, previous cardiac surgery, emergency surgery, type of surgery, and preoperative creatinine levels, with scores ranging from 0 to 17 points (Table 1). It can be used in the preoperative evaluation of AKI and is appropriate for all patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Predicting the development of AKI, its early treatment and prevention are goals of cardiac surgeons and nephrologists involved in the care of these patients, providing an opportunity to develop strategies for early diagnosis and treatment. Recent studies have proposed enhancing the CCS by incorporating additional predictors such as baseline hemoglobin, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), which may improve its predictive accuracy across diverse patient populations (Vives et al., 2024).

| Parameter | Weight |

|---|---|

| Female gender | 1 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 |

| LVEF <35% | 1 |

| Preoperative IABP | 2 |

| COPD | 1 |

| Diabetes with insulin | 1 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 1 |

| Emergency surgery | 2 |

| Surgery type | |

| CABG | 0 |

| Valve only | 1 |

| CABG + Valve | 2 |

| Other cardiac surgeries | 2 |

| Preoperative creatinine | |

| <1.2 mg/dl | 0 |

| 1.2 to <2.1 mg/dl | 2 |

| ≥2.1 mg/dl | 5 |

| Addition of points, minimum score 0, maximum 17 | |

| Points Risk of dialysis | |

| 0–2 0.4% | |

| 3–5 1.8% | |

| 6–8 7.8–9.5% | |

| 9–13 21.5% | |

Notes:

- CABG

-

coronary artery bypass grafting

- COPD

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- IABP

-

intra-aortic balloon pump

- LVEF

-

left ventricular ejection fraction

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the Cleveland Clinic Score before different types of surgery and to assess its usefulness as a predictor of acute kidney injury after elective cardiac surgery.

Materials & Methods

Study design and participants

In this retrospective study, we enrolled 610 patients aged 18 years and older who underwent cardiac surgery between January and December 2023. For this retrospective study, we enrolled 610 patients aged 18 years and older who underwent cardiac surgery between January and December of 2023. We excluded patients who were younger than 18 years old, those who underwent non-elective surgery, and those whose type of surgery was performed fewer than 10 times during this period. If a patient underwent more than one cardiac surgery during the same hospitalization, only the data from the first surgery were considered.

We reviewed the databases and medical records of enrolled patients, collecting the data on their demographic details and medical histories, including important clinical, operative and peri-operative data, such left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), pre- and post-operative serum creatinine level, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE), type of surgery, postoperative complications and treatment, and CCS. The CCS was calculated retrospectively for each patient based on preoperative data extracted from medical records, using the standard formula outlined by Thakar et al. (2005) (Table 1).

We could not distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, so we grouped all diabetic patients into a single category. Because our study was limited to patients with elective surgery, we excluded emergency surgery as a parameter in the Syntax Clinic Score.

Our endpoint was AKI as defined by the Kidney Diseases Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. AKI stage 1 was identified by an increase in serum creatinine of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL (≥26.4 µmol/L) or an increase of 1.5–1.9 times baseline. AKI stage 2 was defined by an increase in serum creatinine of 2–2.9 times baseline. AKI stage 3 was defined by a 3-fold increase in baseline serum creatinine, a serum creatinine increase to four mg/dL (353.6 µmol/L), or the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT). Due to data limitations and the potential effect of postoperative diuretic use, urine output criteria were not included in the KDIGO definition of AKI. This may have led to underdiagnosis of AKI, particularly in cases where urine output was reduced without significant creatinine changes, as urine output is a sensitive early indicator of AKI.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical College of Jagiellonian University (approval number: 118.0043.1.119.2024) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The written informed consent was obtained from the participants upon their admission to the hospital.

Statistical analysis

In this retrospective study, an inferential statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics V29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact test or the chi-2 test and presented as counts and percentages. Differences in continuous variables were tested with the Mann–Whitney U test, presented as median along with interquartile range (IQR) or with the t-Student test, presented as mean with standard deviation (SD).

The test characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values) of CCS as a predictor of AKI were evaluated by constructing ROC curves and calculating the corresponding area under the curve (AUC) values. Statistical significance was determined at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

Between January and December of 2023, a total of 610 patients were admitted for elective surgery (see Table 2). Of those patients, AKI of any stage occurred in 166 patients (27.2%) after elective cardiac surgery. Patients without AKI had fewer comorbidities, such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney injury, atrial fibrillation, and carotid artery disease, compared with patients with AKI. They were also significantly younger (65 vs. 69 years, p < 0.001) and had a higher estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). There were no significant differences between the AKI and non-AKI groups with respect to sex, chronic pulmonary disease, preoperative anemia, coronary or peripheral artery disease, history of stroke, smoking status, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, or type of surgery. Patients with elevated baseline serum creatinine levels and a higher EuroSCORE II score were more likely to develop AKI after cardiac surgery (p < 0.001).

| Parameter | Total (n = 610) | AKI (n = 166) | No AKI (n = 444) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 66 (60–71) | 69 (64–74) | 65 (58–70) | <0.001 |

| Age >65, n (%) | 331 (54.3) | 115 (69.3) | 216 (48.6) | <0.001 |

| Age >70, n (%) | 185 (30.3) | 72 (43.4) | 113 (25.5) | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (% male) | 450 (73.8) | 117 (70.5) | 333 (75.0) | 0.259 |

| Asthma/COPD, n (%) | 80 (13.1) | 21 (12.7) | 59 (13.3) | 0.836 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea, n (%) | 39 (6.4) | 11 (6.6) | 28 (6.3) | 0.886 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 522 (85.6) | 155 (93.4) | 367 (82.7) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 203 (33.3) | 68 (41.0) | 135 (30.4) | 0.014 |

| Impaired Glucose Tolerance, n (%) | 60 (9.8) | 24 (14.5) | 36 (8.1) | 0.019 |

| With insulin treatment, n (%) | 26 (4.3) | 9 (5.4) | 17 (3.8) | 0.386 |

| Chronic kidney injury, n (%) | 59 (9.7) | 39 (23.5) | 20 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 7 (1.1) | 7 (4.2) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Other kidney diseases (cyst, nephrolithiasis), n (%) | 70 (11.5) | 22 (13.3) | 48 (10.8) | 0.400 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 73 (12.0) | 31 (18.7) | 42 (9.5) | 0.002 |

| Anemia, n (%) | 22 (3.6) | 5 (3.0) | 17 (3.8) | 0.630 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 321 (52.6) | 94 (56.6) | 227 (51.1) | 0.226 |

| Carotid Artery Disease, n (%) | 51 (8.4) | 20 (12.0) | 31 (7.0) | 0.044 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 35 (5.7) | 12 (7.2) | 23 (5.2) | 0.333 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 42 (6.9) | 16 (9.6) | 26 (5.9) | 0.101 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 121 (19.8) | 32 (19.3) | 89 (20.0) | 0.832 |

| pCO2 (mmHg), mean (SD) | 37.308 (3.5751) | 37.505 (3.5170) | 37.235 (3.5977) | 0.406 |

| pO2 (mmHg), median (IQR) | 89.4 (81–100) | 88.7 (81.9–98.9) | 89.55 (80.85–100) | 0.980 |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 82 (73–92) | 83 (73–93) | 82 (73–92) | 0.742 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 28.405 (25.6–31.53) | 28.88 (26.45–31.72) | 28.295 (25.39–31.415) | 0.081 |

| BMI >30 kg/m2, n (%) | 216 (35.4) | 65 (39.2) | 151 (34.0) | 0.267 |

| LVEF (%), median (IQR) | 60 (50–60) | 58 (50–60) | 60 (50–60) | 0.267 |

| LVEF =<35, n (%) | 34 (5.6) | 14 (8.4) | 20 (4.5) | 0.060 |

| Creatinine before surgery (μmol/l), median (IQR) | 82 (72–94) | 87 (77–105) | 81 (72.0–91.5) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine maximum level (μmol/l), median (IQR) | 95 (80–118) | 152.5 (122–204) | 87 (74–99) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2), mean (SD) | 81.797 (20.39345) | 65.89 (21.182) | 87.74 (16.565) | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE, median (IQR) | 1.17 (0.82–1.62) | 1.425 (1.12–2.32) | 1.07 (0.755–1.44) | <0.001 |

| CABG, n (%) | 184 (30.2) | 44 (26.5) | 140 (31.5) | 0.229 |

| CABG+AVR, n (%) | 35 (5.7) | 13 (7.8) | 22 (5.0) | 0.174 |

| CABG+CAS, n (%) | 10 (1.6) | 5 (3.0) | 5 (1.1) | 0.103 |

| MIDCAB, n (%) | 52 (8.5) | 9 (5.4) | 43 (9.7) | 0.093 |

| AVR/AVP, n (%) | 216 (35.4) | 66 (39.8) | 150 (33.8) | 0.170 |

| AVR/AVP+reoperation, n (%) | 15 (2.5) | 3 (1.8) | 12 (2.7) | 0.525 |

| AVR/AVP+LAAO, n (%) | 15 (2.5) | 3 (1.8) | 12 (2.7) | 0.525 |

| MVR/MVP, n (%) | 29 (4.8) | 9 (5.4) | 20 (4.5) | 0.636 |

| Bental de Bono, n (%) | 54 (8.9) | 14 (8.4) | 40 (9.0) | 0.824 |

| Length of intensive care unit stay (days), median (IQR) | 1 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | 1 (1–3) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay (days), median (IQR) | 7 (5–10) | 7 (5–13) | 6 (5–9) | 0.002 |

| Return to intensive care unit, n (%) | 20 (3.3) | 16 (9.6) | 4 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Transfusions on intensive care unit, n (%) | 378 (62.0) | 125 (75.3) | 253 (57.0) | <0.001 |

| Rethoracotomy, n (%) | 48 (7.9) | 26 (15.7) | 22 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary complications, n (%) | 114 (18.7) | 54 (32.5) | 60 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory failure, n (%) | 18 (3.0) | 14 (8.4) | 4 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| NIV, n (%) | 47 (7.7) | 21 (12.7) | 26 (5.9) | 0.005 |

| Pleural fluid, n (%) | 58 (9.5) | 32 (19.3) | 26 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Reintubation, n (%) | 14 (2.3) | 14 (8.4) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Tracheotomy, n (%) | 4 (0.7) | 4 (2.4) | 0 | 0.001 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 37 (6.1) | 21 (12.7) | 16 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Wound infection, n (%) | 49 (8.0) | 27 (16.3) | 22 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| VAC/drainage/re-suturing, n (%) | 22 (3.6) | 12 (7.2) | 10 (2.3) | 0.003 |

| CVVHD, n (%) | 17 (2.8) | 15 (9.0) | 2 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Readmission, n (%) | 31 (5.1) | 19 (11.4) | 12 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 18 (3.0) | 10 (6.0) | 8 (1.8) | 0.006 |

| Post-operative inotropic support, n (%) | 160 (26.2) | 62 (37.3) | 98 (22.1) | <0.001 |

| Cleveland Clinic Score, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (1–3) | <0.001 |

| Stage I (scores 0–2), n (%) | 417 (68.4) | 96 (57.8) | 321 (72.3) | <0.001 |

| Stage II (scores 3–5), n (%) | 176 (28.9) | 60 (36.1) | 116 (26.1) | 0.015 |

| Stage III (scores 6–8), n (%) | 16 (2.6) | 9 (5.4) | 7 (1.6) | 0.008 |

| Stage IV (scores 9–13), n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0.102 |

Notes:

P value is presented for the comparison of AKI-group with no-AKI group. Values are mean (SD), n (%), or median (interquartile range).

- ASD/PFO

-

atrial septal defect/patent foramen ovale

- AVR/AVP

-

aortic valve replacement/plasty

- BMI

-

body mass index

- CABG

-

coronary artery bypass graft

- CAS

-

carotid artery stenting

- COPD

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Creatinine level reference range –52-106 μmol/l

- CVVHD

-

continuous veno-venous hemodialysis

- eGFR

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate (normal range >60)

- EuroSCORE

-

European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation

- IQR

-

interquartile range

- LAAO

-

left atrial appendage occlusion

- LVEF

-

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MIDCAB

-

minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass

- MVR/MVP

-

mitral valve replacement/plasty

- NIV

-

non-invasive ventilation

- SD

-

standard deviation

- SI

-

conversion factor for eGFR to ml/s - 0.0167

- TVP

-

tricuspid valve plasty

- VAC

-

vacuum-assisted closure

During the postoperative period, re-thoracotomy, the need for blood transfusions in the ICU, and the need for intravenous inotropic support were more frequent in the AKI group.

Patients with AKI after cardiac surgery, were also more likely to develop postoperative pulmonary complications (including respiratory failure, pleural fluid and pneumonia) and surgical site infection (including deep wound infection necessitating drainage and resuturing). They also spent more time in the hospital (both ICU and postoperative clinic) and had higher hospital mortality. Continuous veno-venous hemodialysis (CVVHD) was used in 15 patients (9%) with AKI and in 2 (0.5%) without AKI (p < 0.001). In patients without AKI, CVVHD has been used for the management of peripheral fluid retention due to postoperative left ventricular failure.

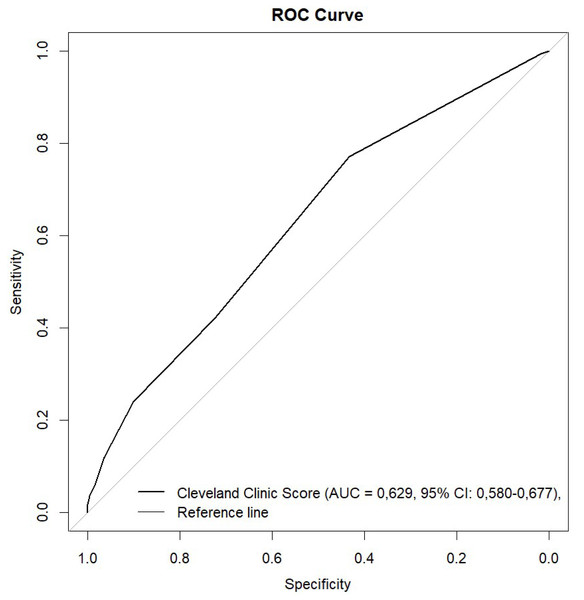

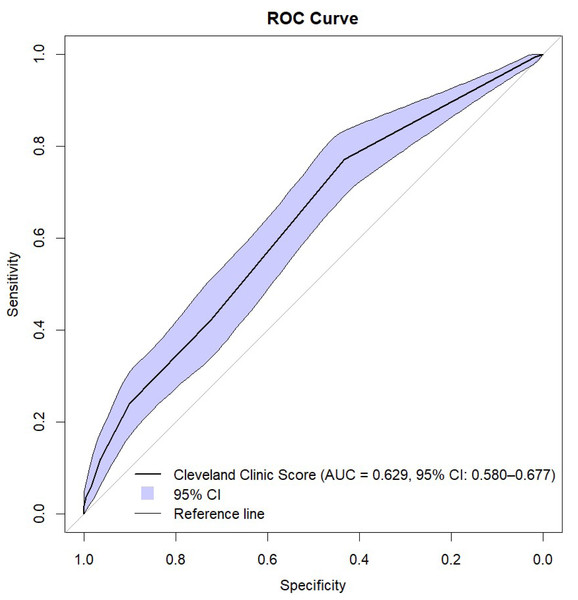

The Cleveland Clinic Scores were significantly higher in the AKI group. Using ROC analysis, CCS showed predictive ability for AKI with need for RRT in all patients with an AUC of 0.630 (95% CI [0.580–0.679]; p ≤ 0.001) (Figs. 1 and 2, Table 3). The results indicate that the Cleveland Clinic score has a high sensitivity of over 70%, with a relatively low specificity of over 40%. This means that it detects the disease with high sensitivity in most patients, but may produce false-positive results in healthy individuals. This is a valuable clinical observation, as it means that the diagnosis of an increased risk of AKI based on CCS requires additional confirmation with other tests and laboratory results. The values were statistically significant for CABG (AUC 0.650; 95% CI [0.552–0.748]; p = 0.003) and aortic valve replacement/plasty (AVR/AVP) (AUC 0.629; 95% CI [0.550–0.709]; p = 0.002). In the case of predictive analysis for CABG and AVR/AVP, for which statistical significance was demonstrated, sensitivity and specificity were 63%, 60% and 75%, 48%, respectively. CCS was predictive for AKI stages II (AUC 0.550; p = 0.057) and III (AUC 0.519; p = 0.464) (Fig. 3, Table 4). The better performance of CCS for CABG and AVR/AVP may be due to shared pathophysiological mechanisms, such as atherosclerosis in coronary artery disease and aortic stenosis, which are captured by CCS components like preoperative creatinine and LVEF (Table 1).

Figure 1: ROC curve.

Figure 2: ROC curve with bootstrap analysis.

Discussion

The true incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients undergoing cardiac surgery is unclear because different authors have used different terminology to define it. In a South Asian cohort of 276 patients, the overall incidence of AKI, as defined by the KDIGO criteria, was 6.88% (Rao et al., 2018). Wong et al. (2015) reported AKI in 14.5% of patients after cardiac surgery. Robert et al. (2010) analyzed a group of 25,086 patients undergoing cardiac surgery in northern New England. According to the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) criteria, AKI occurred in 30% of patients, and according to the Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease (RIFLE) criteria, it occurred in 31%. In our study, acute kidney injury of any stage occurred in 27.2% of patients after elective cardiac surgery according to the KDIGO criteria.

In our study, we identified the following preoperative risk factors for AKI development: greater number of comorbidities, older age, and higher European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) II score. EuroSCORE is a cardiac risk model that predicts 30-day mortality after cardiac surgery. Derived from an international European database, it was first introduced in 1999 and updated to its second version, EuroSCORE II, in 2011 (Nashef et al., 2012).

Preoperative renal impairment has been proven to be an independent risk factor for postoperative mortality. Therefore, creatinine clearance (CCr) was incorporated into EuroSCORE II with three levels of renal insufficiency: moderate (CCr 50–85 mL/min), severe (<50 mL/min), and on dialysis (irrespective of CCr). Thus, elevated EuroSCORE values in AKI patients may reflect reduced preoperative renal function. AKI patients were also more likely to undergo rethoracotomy, receive blood transfusions, and require inotropic support during the perioperative period. All of these postoperative factors are associated with transient renal ischemia. It has been shown that early postoperative AKI after cardiac surgery is strongly associated with two major factors: reduced functional reserve and renal ischemia.

AKI is a frequent complication following cardiac surgery, increasing the risk of mortality, morbidity, prolonged hospital stays, and hospital costs. Identifying patients at high risk for postoperative kidney damage following cardiac surgery is the first step in preventing this complication. Several scoring models have been developed to facilitate risk stratification and improve clinical decision-making (Pannu et al., 2016; Alhulaibi et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2017; Vogt et al., 2021; Dedemoğlu & Tüysüz, 2020; Elmedany et al., 2017).

In our study, we used the CCS, a prognostic tool that assesses the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury. However, it should be emphasized that both the Cleveland Clinic score and the Euroscore depend heavily on preoperative serum creatinine levels, which are the most influential factor. The Canadian study by Wong et al. (2015) evaluated the CCS’s ability to predict both AKI requiring dialysis and less severe stages of AKI in 2,316 patients from a tertiary care center. The study found that the CCS was valid in identifying patients with severe stages of AKI but had less discriminative power for earlier stages.

| Surgery | AUC ROC CCS | 95% Cl | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CABG | 0.650 | 0.552–0.748 | 0.003 |

| CABG+AVR/AVP | 0.680 | 0.489–0.871 | 0.079 |

| CABG+CAS | 0.820 | 0.553–1.000 | 0.095 |

| MIDCAB | 0.602 | 0.386–0.818 | 0.339 |

| AVR/AVP | 0.629 | 0.550–0.709 | 0.002 |

| AVR/AVP+ reoperation | 0.722 | 0.419–1.000 | 0.248 |

| AVR/AVP+LAAO | 0.667 | 0.284–1.000 | 0.386 |

| MVR/MVP | 0.681 | 0.467–0.894 | 0.126 |

| Bental de Bono | 0.468 | 0.281–0.654 | 0.722 |

| All surgery | 0.630 | 0.580–0.679 | <0.001 |

Notes:

- AUC

-

area under curve

- AVR/AVP

-

aortic valve replacement/plasty

- CABG

-

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAS

-

carotid artery stenting

- CCS

-

Cleveland Clinic Score

- LAAO

-

left atrial appendage occlusion

- MIDCAB

-

minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass

- MVR/MVP

-

mitral valve replacement/plasty

Our novel approach was to apply this score to the general cardiac surgical population and evaluate its usefulness with respect to different types of surgery (e.g., CABG, valve surgery). Our analysis suggests that using the CCS to estimate risk by type of surgery may provide more accurate AKI predictions. Most studies have focused on the general use of the CCS score without considering the diversity of surgical procedures, and only a few have differentiated CCS scores for specific types of surgery, such as coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), valve surgery, and other surgeries (Huen & Parikh, 2012).

In our analysis, for the entire study, the AUC ROC CCS was 0.63 (0.580−0.679; 95% CI).

Additionally, we confirmed these results in a bootstrap analysis. When analyzing the clinical usefulness of the test, we assessed that Cleveland Clinic Score has a high sensitivity of over 70%, with a relatively low specificity of over 40%. This means that it detects the disease with high sensitivity in most patients, but may produce false-positive results in healthy individuals.

Our approach revealed that different types of surgery are associated with distinct risk profiles that the CCS can effectively capture with the proper adjustments. ROC analysis demonstrated the statistical power to predict AKI in patients undergoing CABG (AUC 0.650; p = 0.003) and aortic valve replacement/repair (AVR/AVP) (AUC 0.629; p = 0.002) (Fig. 1, Table 3). The pathophysiological mechanisms of AKI after cardiac surgery include ischemia and atheroembolism. Atherosclerosis is the common pathological basis of coronary artery disease and aortic stenosis. This may explain the importance of the CCS in predicting AKI in patients undergoing CABG and aortic valve surgery. However, it should be noted that the small group size may limit the reliability of these findings.

Figure 3: ROC curves for different surgery types.

| Surgery | AUC ROC CCS 1 | 95% Cl | p-value | AUC ROC CCS 2 | 95% Cl | p-value | AUC ROC CCS 3 | 95% Cl | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CABG | 0.411 | 0.310–0.512 | 0.075 | 0.558 | 0.458–0.659 | 0.243 | 0.531 | 0.430–0.631 | 0.542 |

| CABG+AVR/AVP | 0.477 | 0.279–0.676 | 0.824 | 0.484 | 0.282–0.686 | 0.878 | 0.538 | 0.335–0.742 | 0.707 |

| CABG+CAS | 0.500 | 0.125–0.875 | 1.000 | 0.300 | 0.000–0.644 | 0.296 | 0.700 | 0.356–1.000 | 0.296 |

| MIDCAB | 0.380 | 0.158–0.601 | 0.261 | 0.620 | 0.399–0.842 | 0.261 | 0.500 | 0.291–0.709 | 1.000 |

| AVR/AVP | 0.440 | 0.355–0.526 | 0.162 | 0.562 | 0.477–0.648 | 0.146 | 0.498 | 0.414–0.581 | 0.955 |

| AVR/AVP+ reoperation | 0.500 | 0.123–0.877 | 1.000 | 0.375 | 0.000–0.771 | 0.516 | 0.625 | 0.229–1.000 | 0.516 |

| AVR/AVP+LAAO | 0.375 | 0.014–0.736 | 0.516 | 0.625 | 0.264–0.986 | 0.516 | 0.500 | 0.123–0.877 | 1.000 |

| MVR/MVP | 0.403 | 0.171–0.634 | 0.409 | 0.542 | 0.309–0.775 | 0.724 | 0.500 | 0.269–0.731 | 1.000 |

| Bental de Bono | 0.561 | 0.385–0.736 | 0.502 | 0.429 | 0.255–0.602 | 0.430 | 0.511 | 0.332–0.690 | 0.906 |

| All surgery | 0.428 | 0.376–0.480 | 0.006 | 0.550 | 0.498–0.602 | 0.057 | 0.519 | 0.467–0.572 | 0.464 |

Notes:

- AVR/AVP

-

aortic valve replacement/plasty

- AUC

-

area under curve

- CABG

-

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAS

-

carotid artery stenting

- CCS

-

Cleveland Clinic Score

- LAAO

-

left atrial appendage occlusion

- MIDCAB

-

minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass

- MVR/MVP

-

mitral valve replacement/plasty

Many studies propose including additional factors in the scale, such as urine biomarkers (e.g., neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, interleukin-6, hepcidin-25, and midkine), age, body mass index (BMI), and the incidence of arrhythmia and pulmonary hypertension.; serum markers such as lactate, total bilirubin, albumin, white blood cells, cystatin C, and uric acid; cardiopulmonary bypass time; aortic cross-clamp duration; and central venous pressure (Albert et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Che et al., 2019; Palomba et al., 2007; Krzanowska et al., 2024). Introducing these factors into clinical practice could lead to better risk management and improved patient outcomes during surgical procedures.

CCS is primarily used to evaluate the risk of postoperative RRT. In our study, we found that CCS grades 2 and 3 values are just above the reference line, indicating an increased risk of RRT. However, grade 1 is well below this line. These results align with the CCS scale’s assumptions, confirming that the total score and individual stages are effective prognostic tools, particularly for identifying patients requiring postoperative RRT.

It should be noted, however, that further studies are needed to fully verify the usefulness and accuracy of the CCS in different surgical contexts. Therefore, our results may serve as a foundation for future studies aimed at refining the CCS scale to meet the unique requirements of various surgical procedures. Our findings suggest that clinicians can use the CCS scale to identify patients at higher risk for acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy, particularly for coronary artery bypass grafting and aortic valve replacement/aortic valve plasty, enabling targeted preoperative optimization. For milder AKI stages or other surgeries, however, alternative or more refined risk models may be necessary.

Study limitations

Our analysis has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective, single-center study. Second, we included a limited number of patients. Third, we only used creatinine criteria and did not include urine criteria due to data limitations and the postoperative diuretic effect.

Conclusions

Our study found that the Cleveland Clinic Score was a moderate predictor of acute kidney injury and was especially useful in identifying patients who needed renal replacement therapy, especially those undergoing CABG and AVR/AVP procedures. According to our findings, the predictive accuracy of the CCS may be enhanced for different stages of AKI and cardiac surgery types by taking into account variables like advanced age, preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate, and comorbidities like diabetes and hypertension, which demonstrated strong correlations with AKI.