Comparative genomics and phylogenetic analysis of seven Ficus species based on chloroplast genomes

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Diaa Abd El-Moneim

- Subject Areas

- Genomics, Molecular Biology, Plant Science

- Keywords

- Ficus, Comparative genomics, Molecular markers

- Copyright

- © 2026 Bao et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Comparative genomics and phylogenetic analysis of seven Ficus species based on chloroplast genomes. PeerJ 14:e20531 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20531

Abstract

Background

The genus Ficus (Moraceae) is a large and ecologically important group, known for its intricate fig-wasp pollination mutualism and role as a keystone resource in tropical ecosystems. Despite its significance, the phylogenetic relationships within Ficus remain partially unresolved, necessitating more comprehensive genomic data. Chloroplast (cp) genomes are valuable resources for plant phylogenetic and comparative genomic studies. Here, we sequenced, assembled, and comparatively analyzed the complete chloroplast genomes of seven Ficus species, including Ficus esquiroliana, Ficus pandurata, Ficus formosana, Ficus erecta, Ficus carica, Ficus hirta, and Ficus stenophylla.

Results

The complete cp genomes were successfully assembled, ranging in size from 160,340 bp to 160,669 bp, and exhibited a typical quadripartite structure with highly conserved gene content and arrangement. Critically, while some of these species have previously published plastomes, our assemblies consistently encoded 130 genes, contrasting with reported gene counts (e.g., 129 for F. formosana (NC_059898), 119 for F. carica (KY635880), 131 for F. erecta (MT093220)) in earlier studies. Numerous repeat sequences and simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were identified, predominantly in non-coding regions, which serve as valuable resources for developing novel genetic markers. Analysis of codon usage revealed a strong bias towards A/T endings, a common feature in plant cp genomes. While inverted repeat (IR) boundary regions were largely conserved, minor variations, including partial gene duplications (rps19, rpl2), were observed. Comparative genome alignment and nucleotide diversity analysis showed high sequence conservation, with most variations concentrated in single-copy and non-coding regions. We identified three hypervariable regions (ccsA, ccsA - ndhD, and rpoB - trnC-GCA) with elevated nucleotide diversity (Pi > 0.012, ccsA up to 0.0141), suggesting their utility as candidate DNA barcodes for Ficus. Phylogenetic analysis using 79 protein-coding genes from 26 species robustly supported the monophyly of Ficus and resolved the seven newly sequenced species into two well-supported clades, consistent with previous classifications.

Conclusions

Our study provides new, consistently assembled and rigorously annotated chloroplast genome data for Ficus, including clarified data for previously studied species with notable gene content discrepancies. These data identify candidate molecular markers with potential applications for systematics and population genetics, and offer robust insights into relationships among sampled taxa. These data will facilitate future studies of Ficus evolution and conservation when complemented by broader taxon sampling and nuclear/mitochondrial data.

Background

The genus Ficus L. (Moraceae), commonly known as fig trees, comprises one of the largest and most ecologically consequential genera of flowering plants, with over 800 described species largely distributed across tropical and subtropical regions (Berg, 1989; Cruaud et al., 2012). Ficus species are notable for the obligate, species-specific pollination mutualism with agaonid fig wasps—a classic model of coevolution and for their prominent role as keystone resources that sustain frugivores and structure tropical and subtropical forest communities (Zhang et al., 2020; Raji & Downs, 2021; Devi et al., 2022). Several species (e.g., F. carica) are also of economic and ethnobotanical importance as food and in traditional medicine. Despite broad agreement on the monophyly of Ficus, relationships among many infrageneric lineages remain incompletely resolved; causes include ancient rapid radiations, morphological plasticity, hybridization and incomplete lineage sorting (Rønsted et al., 2008; Cruaud et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2020).

Chloroplast genomes have become a routine and powerful resource for plant phylogenetics and comparative genomics because of their generally conserved gene content and organization, uniparental (often maternal) inheritance, and the presence of variable intergenic and coding regions useful for resolving relationships at a range of taxonomic depths (Jansen et al., 2005; Daniell et al., 2016). Advances in high-throughput sequencing have led to a rapid increase in the number of complete plastomes available across angiosperms and within Moraceae, improving our ability to detect mutational hotspots, design lineage-specific markers, and leverage phylogenomic datasets for resolving difficult nodes (Duan et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2022).

Over the past few years, multiple studies have applied complete chloroplast genomes to address systematics and marker development within Ficus. For example, Huang et al. (2022) performed a comparative plastome analysis of ten Ficus species and highlighted mutational hotspot regions and candidate loci for barcoding; Xia et al. (2022) analyzed eight Ficus plastomes and provided phylogenomic insights that supported particular subgeneric groupings; Zhang et al., (2022a) and Zhang et al. (2022b) focused on the F. sarmentosa species complex and used plastomes to clarify relationships among closely related taxa; Vu et al. (2023) sequenced the plastome of F. simplicissima and proposed plastome-derived barcodes for species identification. These investigations consistently show that plastome-scale data increase resolution relative to single-locus markers, but they also reveal that hotspot regions and phylogenetic placements can be sensitive to taxon sampling and geographic representation. In addition, complementary organellar resources are beginning to appear: a recent report of the complete mitochondrial genome of F. hirta (Deng & Cai, 2025) underscores the value of integrating multiple organellar genomes for comparative analyses and for detecting potential shared transfers or assembly artifacts. Comparative plastome studies in other Moraceae genera (Zeng et al., 2022) further illustrate the utility of organellar genomes for resolving genus-level taxonomy and for identifying evolutionarily informative markers.

Despite these advances, taxon sampling across the genus remains incomplete: many sections and geographic lineages of Ficus are still under-represented in plastome datasets, and variation in sampling strategies complicates straightforward comparisons of hotspot loci among studies. To address this gap and to expand available organellar genomic resources for Ficus, we sequenced, assembled and analyzed the complete chloroplast genomes of seven Ficus species (F. esquiroliana, F. pandurata, F. formosana, F. erecta, F. carica, F. hirta, and F. stenophylla). We conducted comprehensive analyses of genome structure, repeat content, codon usage, sequence divergence, and reconstructed their phylogenetic relationships using plastome data. Our findings provide insights into genome evolution and the phylogenetic framework of Ficus, which can facilitate further research on its taxonomy, evolution, and conservation.

Methods

Plant material, DNA extraction, and sequencing

All seven Ficus species examined in this study (F. esquiroliana, F. pandurata, F. formosana, F. erecta, F. carica, F. hirta, and F. stenophylla) were sampled. Voucher specimen information and herbarium accession numbers listed in Table S1; all vouchers are deposited in the Herbarium of Guangxi Institute of Botany. Sampling and collection complied with the regulations of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and consisted of common, non-protected species collected from non-restricted locations.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 50 mg of silica-dried young leaf tissue using the modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Doyle & Doyle, 1987). DNA quality and concentration were assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. High-quality genomic DNA library construction and sequencing were performed by Beijing Gezhi Boya Biotechnology Co., Ltd. DNA was evaluated by Qubit, NanoDrop, and gel electrophoresis, then sonicated using a Covaris S220 to an average insert size of approximately 350 bp. Library construction was performed using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq system (Illumina, San Diego, CA) using a paired-end 2 × 150 bp configuration.

Chloroplast genome assembly and annotation

Raw sequencing reads were filtered to remove low-quality reads and adapters using Trimmomatic version 0.36 (Bolger, Lohse & Usadel, 2014). Clean reads were assembled into complete chloroplast genomes using NOVOPlasty v4.3 (Dierckxsens, Mardulyn & Smits, 2017), with the matK gene used as the seed sequence and the complete chloroplast genome of a related Ficus species (GenBank accession MN364706) supplied as a reference. The assembly accuracy was confirmed by mapping reads back to the assembled genomes. Annotation was performed with Plann version 1.1 (Huang & Cronk, 2015) and manually corrected in Geneious version 10.2.6 (Kearse et al., 2012). The circular genome map was visualized using OGDRAW version 1.3.1 (http://ogdraw.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/) (Greiner, Lehwark & Bock, 2019).

Repeat sequence analysis

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were detected using MIcroSAtellite version 2.1 (MISA, https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa) (Beier et al., 2017) with default parameters (minimum repeat numbers: 10 for mononucleotide, 5 for dinucleotide, 4 for trinucleotide, and 3 for tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide repeats). Long repeat sequences (forward, reverse, palindrome, and complementary) were identified using REPuter version 1.1 (https://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer) (Kurtz et al., 2001) with a minimum repeat size of 30 bp and sequence identity greater than 90%. Tandem Repeats Finder version 4.04 (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html) (Benson, 1999) was used for tandem repeat analysis, with parameters set to 2 for the alignment parameter match and 7 for mismatches and indels.

Codon usage analysis

Protein-coding genes were extracted, and codon usage patterns were analyzed using CodonW version1.4.4 (http://codonw.sourceforge.net/) (Sharp & Li, 1986) to compute the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values. Heatmaps are drawn using TBtools version 2.2.2 (Chen et al., 2020), with RSCU = 1 defined as the neutral (no-bias) value and used as the central point of the color scale (white).

Comparative genome and sequence divergence analysis

Genomic structure visualization and global alignment among the seven Ficus cp genomes were performed using mVISTA (Frazer et al., 2004) in Shuffle-LAGAN mode, with F. hirta as the reference. The borders of the large single-copy (LSC), small single-copy (SSC), and inverted repeat (IR) regions were compared and visualized using IRscope version 3.1 (https://links.jianshu.com/go?to=https://irscope.shinyapps.io/irapp/) (Amiryousefi, Hyvönen & Poczai, 2018).

Nucleotide diversity (Pi) was calculated using DnaSP version 6.0 (Rozas et al., 2017) with a sliding window analysis (window size: 600 bp; step size: 200 bp) to identify highly variable regions among the cp genomes.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted on a concatenated nucleotide alignment of 79 complete chloroplast protein-coding genes (PCGs) from 26 Moraceae taxa (Table S2); Antiaris toxicaria (NC_042884) was used as the outgroup. Subgeneric assignments were adopted following established taxonomic and molecular treatments (Berg, 1989; Rønsted et al., 2008; Cruaud et al., 2012). Sequences were aligned with MAFFT version 7.450 (Katoh & Standley, 2013), and the best-fit model (General Time Reversible (GTR)+F) was determined using ModelFinder in IQ-TREE version 2.0.3 (Minh et al., 2020). Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was conducted with IQ-TREE using 10,000 bootstrap replicates, and Bayesian inference (BI) was performed with MrBayes version 3.2.7 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck, 2003) via four parallel Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs of 1,000,000 generations each, sampling every 500 generations and discarding the first 25% of samples as burn-in. Trees were visualized using FigTree version 1.4.4 (Drummond et al., 2012).

Results

General features

Complete chloroplast genomes for the seven Ficus species (F. esquiroliana, PQ526730; F. pandurata, PQ526731; F. formosana, PQ526732; F. erecta, PQ526733; F. carica, PQ526734; F. hirta, PQ526735; and F. stenophylla, PQ526736) were successfully assembled from Illumina HiSeq paired-end reads (150 bp) using NOVOPlasty software and deposited at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

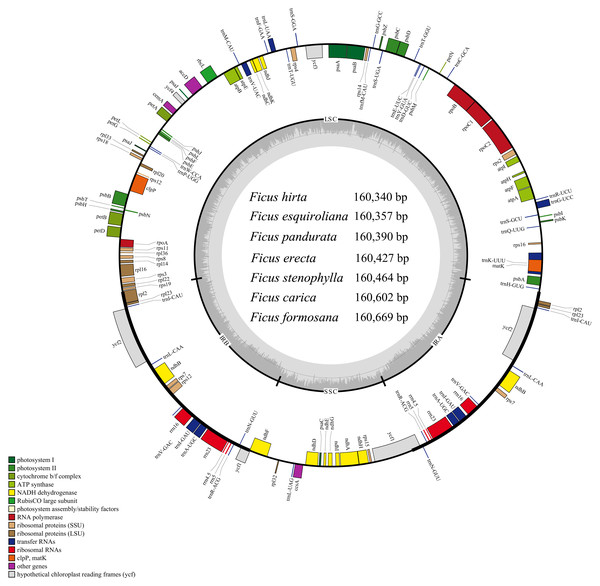

The Ficus plastomes consistently exhibited a typical quadripartite structure with conserved gene content, position, and orientation (Fig. 1), and their sizes, GC contents, numbers of genes, and other information are shown in Table S3. The cp genomes of Ficus species ranged in length from 160,340 bp (F. hirta) to 160,669 bp (F. formosana). The GC content was 35.9%. The total number of annotated genes in Ficus plastomes was 130, comprising 85 (79+6) protein-coding genes (PCGs), 37 (30+7) tRNA genes, and 8 (4+4) rRNA genes. Within these genomes, 18 intron-containing genes were identified (six tRNA and 12 PCGs). Among these intron-containing genes, 15 contain one intron (ndhA, ndhB, atpF, petB, petD, rpoC1, rps16, rpl2, rpl16, trnA-UGC, trnG-UCC, trnI-GAU, trnK-UUU, trnL-UAA, and trnV-UAC), while the other three genes (rps12, clpP and ycf3) contain two introns (Table S4).

Figure 1: Gene map of the seven Ficus species cp genomes.

The innermost shaded areas inside the inner circle correspond to the GC content in the cp genome. Genes in different functional groups are color coded. The boundaries of four regions (IRa, IRb, LSC, SSC) are noted in the inner circle.Repeated sequences

A total of 506 complex repeat sequences, consisting of 210 interspersed repeats (64 forward, nine reverse, 134 palindrome, and three complementary) and 296 tandem repeats, were identified within plastome genomes using MISA, REPuter and Tandem Repeat Finder software, as described in the Material and Methods section (Fig. S1A). For interspersed repeats, the sequence length is mainly concentrated in 30–64 bp, regardless of the forward or palindrome repeats. As for the tandem repeats, most were in the range of 8–26 bp, and a four bp repeat was observed in F. formosana and F. carica within the ycf3 gene. These tandem repeats were mainly distributed in the non-coding LSC and SSC regions.

Microsatellites are small repeating units (one to six nucleotide) within a genome nucleotide sequence (Shukla et al., 2018). The high polymorphism rate of repeat sequences at the species level positions them as common molecular markers valuable for phylogenetic and population genetics studies (Zheng et al., 2020). An analysis of SSRs revealed a count ranging from 89 to 98 in the plastomes (Fig. S1B). The distribution of SSR types was predominantly mononucleotide repeats (59%), among which A/T repeats were the most numerous. Dinucleotides were the next most frequent at 22%, and tetranucleotides made up 9%, with other SSR types occurring at lower rates (Figs. S1C; S1D). This composition pattern suggests that mononucleotide repeats potentially play a greater role in genetic variability than other SSR types. Our finding that A/T repeats were most abundant is similar to reports from other studies (Munyao et al., 2020). Analysis of SSR locations further indicated that the majority were situated in non-coding, intergenic, and intron regions. These SSRs offer potential for developing specific markers crucial for systematic, evolutionary, and conservation studies in Ficus.

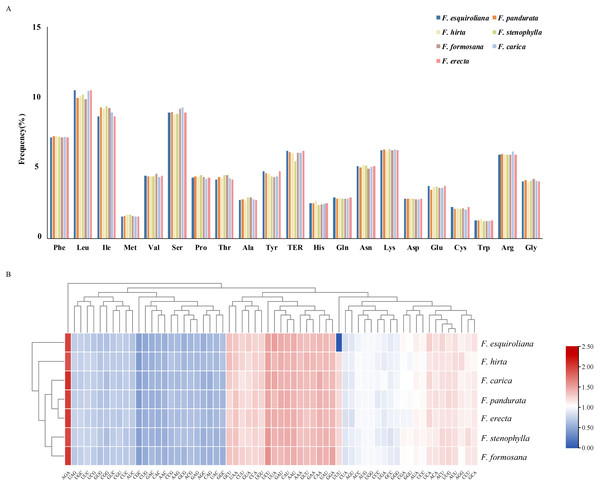

Codon usage

The patterns of codon usage and nucleotide composition contribute to establishing a theoretical foundation for the genetic modification of cp genomes (Mazumdar et al., 2017). A comprehensive analysis was conducted on the codon usage frequency of protein-coding genes within the chloroplast genomes of seven assembled species of Ficus. The study revealed 64 distinct RSCU values within the plastomes of these Ficus species. These genomes contain between 53,455 and 53,556 codons, with F. hirta containing the fewest and F. formosana containing the most. Among all the codons, leucine (Leu) emerged as the most prevalent amino acid, with a frequency ranging from 9.7 to 10.49%. This was followed by isoleucine (Ile), with a frequency between 8.64% and 9.35%. Conversely, tryptophan (Trp) was the least abundant, with a frequency of 1.21–1.35% (Fig. 2A). Methionine and tryptophan are each encoded by a single codon (ATG and TGG, respectively); therefore their RSCU values are 1.00 by definition and RSCU is not informative for assessing synonymous codon bias for these amino acids. Thirty codons were identified with an RSCU value greater than 1. Among them, except for UUG (Leu) and AGG (Arg), all codons ended with A or U(T) nucleotides (Fig. 2B). This observation suggested a preference for A and T as the terminal bases in codons.

Figure 2: (A) Relative frequency of each amino acid (expressed as a percentage) in seven Ficus species (B) Heat map analysis for relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values of all protein-coding genes of seven complete chloroplast genomes in.

Red and blue indicates higher and lower RSCU values, respectively.Comparative analysis between seven Ficus species

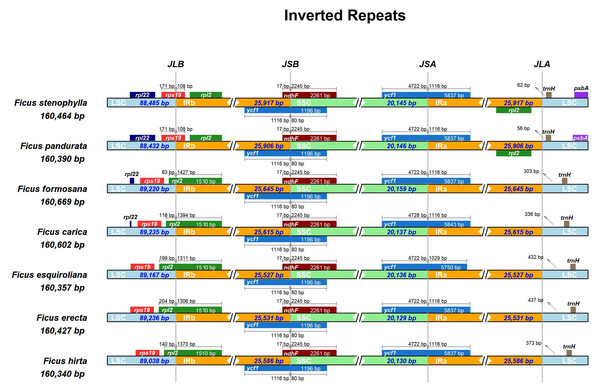

The expansion and contraction of the IR region are major driving forces in the evolution of land plants (Kode et al., 2005; Raubeson et al., 2007; Yao et al., 2015; Abdullah Mehmood et al., 2020). In this study, we compared the positions of the LSC/IR junction (JL) and the IR/SSC junction (JS) across seven assembled Ficus plastomes (Fig. 3). The lengths of the IR regions were relatively uniform, ranging from 25,527 to 25,917 bp, indicating high conservation with minimal contraction/expansion across the seven Ficus plastomes. The JL (IR-LSC: rpl2 & rps19) boundary showed high similarity in seven Ficus plastomes, except for F. pandurata and F. stenophylla. At the IR-LSC boundary, the rps 19 gene crossed into the IR region by approximately 108 bp in F. pandurata and F. stenophylla, while it remained entirely in the LSC region in the other five species. The JS (IR-SSC: ycf1 & ndhF) boundaries were also highly similar in Ficus plastomes. The ycf1 gene crossed the IR-SSC border and extended into the IR region at approximately 1,116 bp. Concurrently, the ndh F gene consistently extended into the IRB region by 17 bp in all species, with the remainder of the gene located in the SSC. At the JSA (SSC-IRA) boundary, the ycf1 gene partially extended into the SSC region for all species, with its segment in SSC measuring 4,722 bp in six species and 4,728 bp in F. esquiroliana. At the JLA (IRA/LSC) boundary, the length of the intergenic spacer between the boundary and the trnH gene, which is located in the LSC region, exhibits significant variation among different species, ranging from 56 bp in F. pandurata to 437 bp in F. erecta.

Figure 3: Comparison of the borders of LSC, SSC, and IR regions among chloroplast genomes of Ficus.

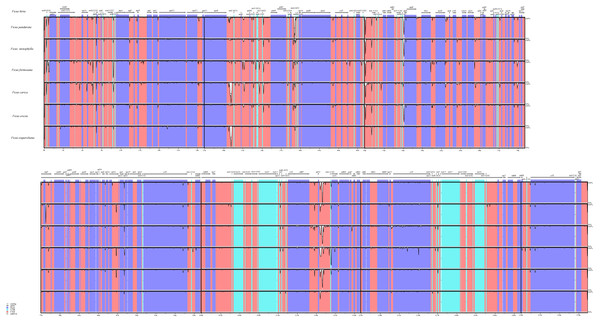

The number of base pairs (bp) represents the distance from the boundary to the end of the gene. JL, junction between the large single-copy region (LSC) and the inverted repeat (IR); JS, junction between the Inverted Repeat (IR) and the small single-copy region (SSC).We also analyzed the differences in the cp genomes among the seven species through global sequence alignment (Fig. 4). Using mVISTA for global sequence alignment, with F. hirta sequence and annotation file as references, we observed variations across different regions among the seven species. The results indicated that the seven chloroplast genomes are highly conserved. Furthermore, the alignment revealed higher sequence conservation in coding regions compared to non-coding regions, and in inverted repeat regions relative to single-copy regions (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Visualized alignment of the Ficus chloroplast genome sequences with annotations using mVISTA.

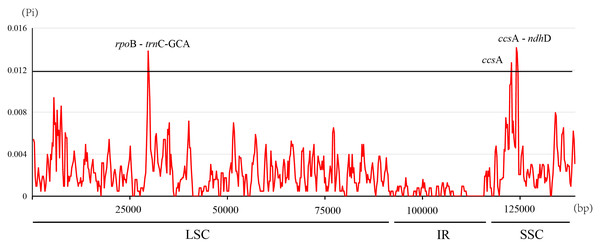

Each horizontal lane shows the graph for the sequence pairwise identity with F. hirta as reference. The x-axis represents the base sequence of the alignment and the y-axis represents the pairwise percent identity within 50–100%. Gray arrows represent the genes and their orientations. Dark-blue boxes represent exon regions; light-blue boxes represent untranslated regions; red boxes represent conserved non-coding sequence (CNS) regions.The nucleotide diversity (Pi, π) within Ficus plastomes ranged from 0 to 0.0141, with a mean value of 0.0022. Inverted repeat (IR) regions exhibited low nucleotide polymorphism, and the majority of variations were localized to the large single-copy (LSC) and small single-copy (SSC) regions (Fig. 5). While protein-coding regions demonstrated overall conservation across these plastomes, three gene regions (ccsA, ccsA - ndhD, and rpoB - trnC-GCA) displayed significantly elevated Pi values (>0.012). Notably, ccsA exhibited the highest divergence, reaching a Pi value of 0.0141 (Fig. 5). These polymorphic loci serve as promising candidate barcode sequences for phylogenetic inference and population genetic studies within Ficus.

Figure 5: Nucleotide diversity in the Ficus chloroplast genomes.

Phylogenetic analysis

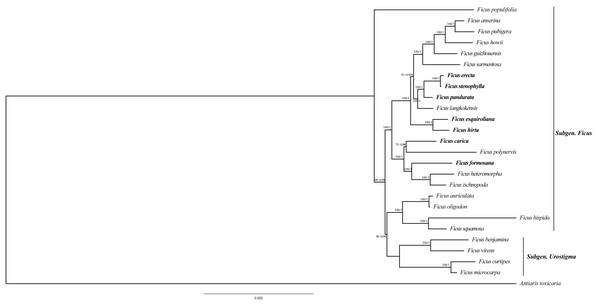

To ascertain the phylogenetic relationships among Ficus species, we employed 79 PCGs from 26 species to reconstruct phylogenetic trees. The results indicate that the topology generated by distance estimation using the best fit model (GTR+F) is consistent under two different reconstruction methods (ML and BI) (Fig. 6). All Ficus species formed a monophyletic clade, separate from the outgroup Antiaris toxicaria. Notably, all seven newly sequenced plastomes in this study are assigned to Subgen. Ficus (Table S2) and are distributed into two strongly supported subclades (Fig. 6). Within one clade, F. hirta, F. esquiroliana, F. erecta, F. stenophylla, F. pandurata, and F. langkokensis clustered together with 100% bootstrap support, indicating a close relationship among these species. Within the other clade, F. carica, F. polynervis, F. formosana F. heteromorpha, and F. ischnopoda clustered together, suggesting a close relationship. All branches had support rates above 70%.

Figure 6: Maximum likelihood tree and Bayesian tree were constructed based on CDS data partitions of 26 species chloroplast genomes.

The number on the branches as Bayesian inference posterior probability/maximum likelihood bootstrap support values. Branch lengths represent the expected number of substitutions per site (scale bar = 0.002 substitutions per site).Discussion

This study presents the complete chloroplast genomes of seven Ficus species, contributing to the understanding of cp genome evolution, sequence divergence, and phylogenetic relationships within the genus. The plastomes exhibited a typical quadripartite structure with highly conserved gene content, order, and orientation, which is consistent with previous reports of other members of Moraceae and angiosperms more broadly (Jansen et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2022a; Zhang et al., 2022b). The minimal variation in overall genome sizes (160,340–160,669 bp) and the uniform GC content of approximately 35.9% further reflect the characteristic slow structural evolution and high conservation of chloroplast genomes in land plants.

Repeat Sequences and SSRs

We found a substantial number of complex repeat sequences and simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in the Ficus plastomes. The predominance of mononucleotide (A/T-rich) SSRs is a common feature in angiosperm chloroplast genomes (Munyao et al., 2020; Provan, Powell & Hollingsworth, 2001), likely reflecting underlying mutational biases and relaxed selection in non-coding regions. These identified SSRs and other repeat motifs represent valuable resources for developing high-resolution genetic markers, which can be applied in population genetics, phylogeography, and species identification within Ficus (Zhang et al., 2022a; Zhang et al., 2022b). The observed distribution of SSRs, mainly in non-coding regions, also supports their utility as informative hotspots for molecular marker development.

Codon usage bias

Analysis of codon usage revealed a strong bias toward codons ending in A or T, consistent with the compositional bias in angiosperm chloroplast genomes (Mazumdar et al., 2017). This bias may reflect selection for translational efficiency, mutational pressures, or a combination of both. The predominance of leucine and isoleucine codons, and the low frequency of tryptophan, is in line with findings from other plant cp genomes (Morton, 1998). Such codon usage patterns provide fundamental information for future studies of plastome gene expression and for potential transplastomic engineering in Ficus.

IR boundary dynamics

The expansion and contraction of inverted repeat (IR) regions are known to contribute to size variation and evolutionary novelty in plastid genomes (Wang et al., 2008; Xiong et al., 2009). Our comparative analysis of the seven Ficus chloroplast genomes revealed a generally conserved quadripartite structure, with IR region lengths ranging from 25,527 bp to 25,917 bp, indicating relative stability within this genus. However, detailed examination of the LSC/IR and IR/SSC junctions (Fig. 3) unveiled minor yet discernible variations, reflecting dynamic micro-evolutionary shifts. The presence of partial rps19 and rpl2 duplications at the respective boundaries suggests that both lineage-specific and potentially ongoing border shifts may occur within Ficus. However, the relatively limited IR boundary variation suggests a largely stable cp genome structure in this genus, compared to the more dramatic IR dynamics seen in some other angiosperms.

Potential molecular markers in Ficus

Global sequence alignment and nucleotide diversity (Pi) analyses demonstrated that, as expected, the IR regions were the most conserved while the single-copy regions especially non-coding and intergenic spacers exhibited higher sequence divergence. The identification of three highly variable regions (ccsA, ccsA - ndhD, and rpoB - trnC-GCA) with elevated Pi values highlights their potential as candidate DNA barcodes for Ficus systematics and population studies. These hypervariable loci may facilitate more precise species delimitation and phylogeographic analyses, potentially complementing or providing higher resolution than existing universal barcode regions such as matK and rbcL (CBOL Plant Working Group, 2009).

Phylogenetic analysis in Ficus

Phylogenetic reconstruction based on a concatenated alignment of 79 chloroplast protein-coding genes robustly resolved relationships among the seven newly sequenced Ficus species nested within a monophyletic Ficus clade (26 taxa sampled). The recovered topology, which is consistent between ML and BI analyses and shows high support across nodes, identifies two major subclades that correspond well with previously recognized divisions based on nuclear and plastid markers (Rønsted et al., 2008). In our sampling most newly sequenced taxa are assigned to Subgen. Ficus and are distributed across two well-supported subclades; a small set of Subgen. Urostigma taxa were included to provide taxonomic context.

While plastome-scale data markedly improve resolution relative to single- or few-locus approaches and can help resolve recent radiations, chloroplast genomes represent a single, typically uniparentally inherited locus and therefore may not fully capture complex reticulate histories (e.g., hybridization, introgression, incomplete lineage sorting) that are likely in diverse genera such as Ficus. Moreover, our sampling-seven new plastomes within a genus of >800 species-remains limited. To more rigorously assess subgeneric monophyly and the deeper relationships within Ficus will require denser taxon sampling across recognized subgenera and integration of nuclear (and mitochondrial) genomic datasets. Finally, organellar complementarity deserves mention. While chloroplast genomes provide a relatively straightforward single-locus phylogenomic perspective, mitochondrial genomes and nuclear datasets provide independent and complementary histories. The recent publication of the complete mitochondrial genome of F. hirta (Deng & Cai, 2025) highlights an opportunity for combined organellar analyses; for example, comparisons of shared repeats, transferred sequences, or conflicting topologies between organellar genomes may help detect events such as introgression or assembly artifacts. We therefore encourage future work that integrates chloroplast, mitochondrial and nuclear genomic data, coupled with denser taxon and geographic sampling, to provide a more complete picture of Ficus evolutionary history.

Conclusions

We present seven additional complete chloroplast genomes for Ficus species, expanding available organellar genomic resources for the genus. Comparative analyses revealed conserved quadripartite genome structure, lineage-specific minor IR boundary variation, abundant A/T-biased SSRs concentrated in noncoding regions, codon usage bias toward A/T endings, and several hypervariable regions (ccsA, ccsA - ndhD, rpoB - trnC-GCA) that are promising candidate loci for species delimitation and population studies. These plastome data, when integrated with denser taxon sampling and nuclear/mitochondrial datasets, will aid future studies of Ficus systematics, biogeography, and conservation.

Supplemental Information

Quantitative analysis of various repeat types in Ficus chloroplast genomes

(A) The number of Dispersed repeat and Tandem repeat; (B) Number of various SSR repeat types; (C) The proportion of SSR repeat types across all seven species; (D) Number of SSRs in each species.