Significance of neuroendocrine systems and the gut-brain axis (GBA) in the regulation of obesity

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Lesley Anson

- Subject Areas

- Diabetes and Endocrinology, Neurology, Obesity

- Keywords

- Obesity, Neuro-endocrine systems, White adipose tissues, Brown adipose tissues, Gut-Brain axis

- Copyright

- © 2026 Zhao et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Significance of neuroendocrine systems and the gut-brain axis (GBA) in the regulation of obesity. PeerJ 14:e20400 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20400

Abstract

Obesity is a major global public health issue due to its high morbidity and mortality rates, with its prevalence increasing annually. According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, the global population of individuals with obesity has doubled from 1990 to 2022, with over 650 million adults with obesity experiencing metabolic abnormalities such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Various approaches have been used to treat or prevent obesity including lifestyle interventions, surgery, and pharmacological therapies aimed at reducing energy absorption and increasing energy expenditure. However, these methods do not significantly reduce energy stored in adipose tissues. The conversion of white adipose tissue (WAT) to brown adipose tissue (BAT) presents a promising therapeutic target for obesity treatment. Notably, there is a substantial loss of BAT in individuals with obesity. Conversely, increased BAT is associated with a lower body mass index (BMI), younger age, lower glucose levels, and a decreased incidence of cardiometabolic diseases. Research indicates that BAT formation is modulated by neuro endocrine systems, suggesting a promising therapeutic strategy for obesity prevention and treatment by targeting these systems. In this review, we first discuss the regulation and signaling pathways of neuroendocrine systems involved in energy balance. We then explore the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the onset and pathogenesis of obesity and their relationship with neuroendocrine systems. In particular, we summarize the role of the gut-brain axis (GBA) in obesity.

Introduction

Obesity originates from an imbalance between caloric intake and energy expenditure, promoting the expansion of subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) and the excessive accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) (Seravalle & Grassi, 2017). Obesity can trigger changes in hormone secretion and chronic inflammation (Marcelin et al., 2019). It can also lead to chronic metabolic dysfunction, inducing diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, fatty liver, cardiovascular diseases, and gastrointestinal cancers (Piché, Tchernof & Després, 2020; Zou & Pitchumoni, 2023). Over the past century, as the economy has thrived, the population of individuals with obesity has increased sharply due to improved living standards, medical treatments (hypoglycemic drugs, glucocorticoid drugs, antidepressant drugs, etc.), and diet quality (high-calorie and low-nutrition). Current estimates suggest that by 2025, more than 21% of women worldwide will be obese (Poston et al., 2016; Steinbach et al., 2024). The obese population tends to be younger, representing a global public health crisis. By 2022, 160 million children and adolescents were living with obesity (http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight). Overall, obesity significantly impacts the quality of life and can cause social problems.

White adipose tissue (WAT) is crucial for maintaining whole-body energy homeostasis, acting as a source of circulating free fatty acids during fasting and as the primary site for the storage of energy such as triglycerides (TG) (Rabadán-Chávez, Díaz de la Garza & Jacobo-Velázquez, 2023). Unhealthy human lifestyles, including abnormal and excessive caloric intake, can lead to the accumulation of glycogen and the increased formation of lipid storage of TGs, termed ”abnormal adipogenesis”, which is a primary cause of obesity (Rabadán-Chávez, Díaz de la Garza & Jacobo-Velázquez, 2023). Brown adipose tissue (BAT) is a thermogenic organ that contributes to non-shivering thermogenesis, activated under cold stress through the sympathetic nervous system (Hachemi & U-Din, 2023). At the molecular level, the activation of BAT’s thermogenic capacity is regulated by uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), which is in turn modulated by numerous factors such as diet (Argentato et al., 2018). Additionally, BAT helps maintain multiple organs, including skeletal muscle, the intestine, the central nervous system (CNS), and the immune system, to control whole-body glucose homeostasis and energy balance (Gaspar et al., 2021). BAT has a superior energy dissipation capacity compared to WAT and muscles (Hachemi & U-Din, 2023). Therefore, research targeting the facilitation of WAT to BAT transformation is a promising avenue for combating obesity. Notably, the transformation of WAT to BAT, as well as adipose function, are dependent on neuroendocrine regulation (Zhu et al., 2019).

The gut-brain axis (GBA) is a complex bidirectional communication network connecting the gut and brain, involving neural, immune, and endocrine communication pathways between the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and the central nervous system (CNS) (Zheng et al., 2023). Several alterations in the gut microbiome contribute to changes in the nervous system, leading to insulin resistance and obesity (Asadi et al., 2022). Therapeutic strategies targeting the transplantation and supplementation of the gut microbiome offer novel therapies against obesity.

In this review, we describe the cellular and molecular mechanisms regulating neuroendocrine systems. We further examine the signaling cascades of neuroendocrine systems involved in energy balance. Additionally, we summarize the concept of obesity and the importance of neuroendocrine systems in regulating adipogenesis, particularly the modulation of WAT to BAT transformation and the role of the GBA in this process. Finally, we discuss current anti-obesity approaches based on neuroendocrine regulation and the GBA.

Survey methodology

This review is the result of a systematic literature search conducted on PubMed and Web of Science. The purpose was to search for relevant articles published from 2005 to 2024 on the regulation and signaling pathways of the neuroendocrine system involved in energy balance. Inclusion criteria: Articles were included if they (1) focused on the neuroendocrine regulation of energy balance or its association with obesity; (2) provided data on signaling pathways, molecular mechanisms, or clinical/experimental evidence; (3) were original research articles, reviews, or meta-analyses. Exclusion criteria: Studies were excluded if they (1) were not related to neuroendocrine regulation or energy balance; (2) were case reports, letters to the editor, or conference abstracts without full data; (3) contained duplicate data from the same research group; (4) had unclear methodology or incomplete results.

We also reviewed the relevant references cited in articles to ensure comprehensive coverage and impartiality.

Audience

This article reviews the molecular and cellular mechanisms that affect the pathogenesis of obesity and their relationship with the neuroendocrine system. This work also summarizes the role of the gut-brain axis in obesity. This will help readers understand the pathogenesis of obesity, review treatment and prevention strategies, and consider new ideas and targets for the development of drugs to treat obesity. Therefore, this article is considered suitable for a diverse readership.

Endocrine systems

The body regulates energy metabolism primarily through the neuroendocrine system, with the hypothalamus serving as the central regulator of adaptive thermogenesis. This regulation involves several key hormonal systems. Typical endocrine hormones influence metabolic activity and energy expenditure by acting on hypothalamic neurons or by directly innervating metabolic tissues via the sympathetic nervous system (Roh & Kim, 2016). Obesity-related hormones and their corresponding receptors are shown in Table 1.

Thyroid hormones

The thyroid gland, the largest endocrine gland in the human body, secretes hormones crucial for sympathetic nervous system activity, significantly influencing thermogenesis and energy metabolism. Thyroid hormones exert their effects through thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) within tissues and organs (Mullur, Liu & Brent, 2014). The thyroid primarily secretes thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) (Bianco et al., 2019). TRα is primarily involved in thermogenesis, while TRβ is associated with cholesterol metabolism and lipogenesis (Obregon, 2008). Research shows that mice lacking TRα are leaner and have higher energy expenditure (Pelletier et al., 2008). TRβ can regulate genes essential for preadipocyte proliferation and adipocyte differentiation through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) (Obregon, 2008). Mice with an adipose tissue-specific TRβ knockout are more prone to obesity and metabolic disorders under high-fat diet conditions (Ma et al., 2023). However, synthetic TRβ agonists can reduce cholesterol, triglycerides, and obesity, indicating a potential therapeutic mechanism (Grover, Mellström & Malm, 2007; Lu & Cheng, 2010).

| Hormones and their abbreviations | Receptors and their abbreviations |

|---|---|

| Thyroxine | Thyroid hormone receptor α (TRα), Thyroid hormone receptor β (TRβ) |

| Leptin | Leptin receptor (LepR) |

| Insulin | Insulin receptor (INSR) |

| Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) | G-protein-coupled melanocortin 3 receptor (MC3R), G-protein-coupled melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) |

| Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) | It has not yet been determined |

| Peptide YY (PYY) | Neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor |

| Pancreatic Polypeptide (PPY) | Neuropeptide Y Y4 receptor |

| Ghrelin | growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR) |

| Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) | Glucagon-like Peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) |

| Cholecystokinin (CCK) | Cholecystokinin A receptor (CCKAR) |

| Estrogen | Estrogen receptor α (ERα), Estrogen receptor β (ERβ) |

| Androgen | Androgen receptor (AR) |

| Hypocretin/Orexin (HCRT) | Hypocretin receptor (HCRTR) |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) | Tyrosine receptor kinase B (TRKB) |

| Nesfatin-1 | It has not yet been determined |

| Nesfatin-1-like peptide (NLP) | It has not yet been determined |

| Oxytocin (OXT) | Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) |

Both TRα and TRβ receptors are expressed in adipose tissue. Brown adipocytes express a large amount of deiodinase, which converts thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) and subsequently inhibits the activity of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. This process promotes the transcription of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) through binding to nuclear receptors, leading to increased brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis. Additionally, T3 enhances sympathetic nervous activity, promoting the browning of white adipose tissue (WAT) (López et al., 2013; Martínez-Sánchez et al., 2017). Compared to individuals with normal thyroid function, those with hypothyroidism have lower T4 and T3 levels and higher thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, making them more prone to obesity, especially severe obesity (Biondi, 2010).

Leptin

Leptin, encoded by the Lep gene, is primarily synthesized by white adipose tissue. It plays a crucial role in the negative feedback regulation of the hypothalamus and adipose tissue, as well as in body weight regulation by binding to and activating the leptin receptor (LepR) (Zhang et al., 1994). The neural mechanisms by which leptin regulates energy metabolism primarily involve the neuropeptide Y (NPY) and the melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) systems. Upon binding to its receptor, leptin acts on the satiety center of the hypothalamus, inhibiting the synthesis and release of NPY from Agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons in the arcuate nucleus, thus reducing appetite. It also activates proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, increasing MSH levels and suppressing feeding through leptin receptor binding (Brüning & Fenselau, 2023). Generally, AgRP neurons are activated in response to insufficient food intake and decreased leptin levels to promote hunger and appetite, whereas POMC neurons are activated in response to sufficient food intake and increased leptin levels to suppress hunger and transmit satiety signals.

Upon binding to the leptin receptor, leptin recruits and activates JAK2 (Janus kinase 2), leading to the phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues (Tyr985, Tyr1077, and Tyr1138) within the leptin receptor. This phosphorylation activates signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, primarily STAT3, in leptin receptor-mediated signaling (Bendinelli et al., 2000; Kloek et al., 2002). Different STATs are involved in leptin receptor signaling across various cell types (Bendinelli et al., 2000). Phosphorylated STAT3 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to POMC and AgRP promoters, upregulating POMC expression and downregulating AgRP and NPY expression, and ultimately reducing food intake. JAK2 can also phosphorylate insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2), leading to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activation. This, in turn, activates protein kinase B (PKB or AKT), inhibiting Forkhead box protein O1 (Foxo1) activity and promoting the binding of STAT3 to POMC and AgRP promoters. PI3K can also activate phosphodiesterase 3B (PDE3B), which reduces cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels and promotes STAT3 dimerization (Sahu, 2011; Zhao et al., 2002). Additionally, AKT can activate the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the hypothalamus and phosphorylate S6K. Inhibition of mTOR attenuates leptin’s anorexigenic effects (Cota et al., 2006), while systemic deletion or inhibition of S6K1 abolishes leptin’s anorexigenic effects (Blouet, Ono & Schwartz, 2008; Cota et al., 2008).

Phosphorylated leptin receptors can also activate SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2), which, upon activation, binds to growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2). This interaction activates the Son of Sevenless (SOS), Ras, and Raf proteins, leading to ERK phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, which initiates the transcription of relevant genes. Neuron-specific deletion of SHP2 results in obesity and leptin resistance in mice (Zhang et al., 2004). Blocking ERK1/2 in the hypothalamus can negate leptin’s anorexigenic effects in rats and prevent leptin-induced sympathetic activation of brown adipose tissue (Rahmouni et al., 2009).

Leptin also inhibits AMPK activity in the hypothalamus, increasing acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) activity and exerting anorexigenic effects (Gao et al., 2007; Minokoshi et al., 2004). It can also inhibit ACC activity in skeletal muscle, accelerating fatty acid oxidation (Minokoshi et al., 2024). Recent studies have identified a novel type of LepR neurons that are characterized by the expression of basonuclin 2 (BNC2) and are known as BNC2 neurons. These neurons, activated by feeding and leptin stimulation, rapidly suppress appetite. In addition to appetite control, activation of these neurons reduces blood glucose levels and enhances insulin sensitivity. Deletion of leptin receptors in BNC2 neurons leads to increased food intake and obesity (Tan et al., 2024).

Leptin resistance refers to a reduced tissue response to leptin’s effects. Studies suggest that abnormalities may exist in the leptin transport systems of obese patients (Caro et al., 1996a; Schwartz et al., 1996). Impaired blood–brain barrier (BBB) function affects leptin transport, and central administration of leptin can reduce food intake and body weight in diet-induced obese mice, indicating a link between leptin resistance and the BBB (Van Heek et al., 1997). Genetic mutations in the leptin receptor can also lead to leptin resistance (Caro et al., 1996b; Qiu et al., 2001). In leptin’s negative feedback regulation, negative regulators such as suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibit leptin signaling and prevent excessive activation of the leptin signaling pathway (Bjorbak et al., 2000; Münzberg, 2010).

Insulin

Insulin is a protein encoded by the insulin gene and is composed of A and B peptide chains linked by disulfide bonds (Steiner & Oyer, 1967). Insulin acts on the insulin receptor (INSR), which is present in various tissues including the hypothalamus (Benecke, Flier & Moller, 1992; Gerozissis, 2004; Wada et al., 2005).

Intracerebroventricular injection of insulin in baboons leads to reduced food intake and weight loss (Woods et al., 1979), and similar effects are observed with hypothalamic injections in rats (McGowan et al., 1990). Reducing INSR expression in the hypothalamus or conditionally knocking out INSR in neuronal tissues of mice results in increased food intake and weight gain (Brüning et al., 2000; Obici et al., 2002). Insulin has been shown to increase POMC neuron activity and upregulate POMC expression through the PI3K/AKT/Foxo1 signaling pathway, in conjunction with leptin (Kitamura et al., 2006; Niswender, Baskin & Schwartz, 2004; Spanswick et al., 2000; Taniguchi, Emanuelli & Kahn, 2006; Varela & Horvath, 2012).

Insulin resistance is a reduced response of tissues to insulin’s effects. Although obesity and insulin resistance often overlap, they are not identical; some individuals exhibit insulin resistance without obesity, while others are obese without demonstrating insulin resistance (Samocha-Bonet et al., 2014). Mice with adipose tissue-specific conditional knockout of INSR display phenotypes opposite to those with hypothalamic INSR knockout, as adipocytes require insulin for fat deposition (Blüher et al. 2002). This indicates that not all tissues possess equal resistance to insulin; only insulin resistance in the liver, muscle, and brain leads to hyperinsulinemia and obesity (Kitamura, Kahn & Accili, 2003).

POMC/αMSH/CART

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) is a polypeptide encoded by the POMC gene. It serves as a precursor for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), α-, β-, and γ-melanocyte-stimulating hormones (MSH), and β-endorphin. These are produced through a series of post-translational proteolytic cleavages that are primarily controlled by the serine proteases prohormone convertase 1 and 2 (PC1 and PC2) (Pritchard, Turnbull & White, 2002; Smith & Funder, 1988). POMC is expressed in the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary, intermediate pituitary, nucleus of the solitary tract, immune system, and skin. In the central nervous system, POMC expression is restricted to the arcuate nucleus (ARC) and nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), which are both capable of producing PC1 and PC2. The ARC produces α-, β-, and γ-MSH, while the NTS produces α-MSH and β-endorphin (Bronstein et al., 1992; Meister et al., 2006; Young et al., 1998).

The receptors for POMC proteins, G protein-coupled melanocortin receptors (MCRs), are diverse in function. MC1R is responsible for skin pigmentation (melanocytes); MC2R is involved in ACTH-induced steroidogenesis (adrenal glands); MC3R and MC4R regulate appetite and body weight; and MC5R is involved in temperature regulation (Chen et al., 1997; Clark, McLoughlin & Grossman, 1993; Jégou, Boutelet & Vaudry, 2000; Mountjoy et al., 1994; Rousseau et al., 2007). MC4R is primarily found in the dorsomedial nucleus (DMN), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), and lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), as well as in the cortex, thalamus, brainstem, and spinal cord (Mountjoy et al., 1994). MC3R is exclusively located in the ARC (Jégou, Boutelet & Vaudry, 2000). Mice with MC4R knockout exhibit severe hyperphagia and obesity (Huszar et al., 1997), and dominant mutations in MC4R are the most common cause of monogenic obesity in humans (Vaisse et al., 1998; Yeo et al., 1998). Rats with MC3R knockout show reduced appetite and fat accumulation but may not be overweight, while double knockout of MC3R and MC4R leads to more severe hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia compared to MC4R knockout alone (Butler et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2000; You et al., 2016).

Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) is a protein encoded by the CARTPT gene that is found in the ARC, pituitary, midbrain, and adrenal medulla (Douglass & Daoud, 1996; Koylu et al., 1998; Koylu et al., 1997). POMC/CART neurons project to the PVN to regulate thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) release (Fekete et al., 2000a; Fekete et al., 2000b). They also project to the DMN, ARC, and LHA, regions associated with appetite and body weight regulation (Bagnol et al., 1999; Millington, 2007). Intracerebroventricular injection of CART in rats has been shown to inhibit food intake (Kristensen et al., 1998; Lambert et al., 1998), and CART knockout mice exhibit increased food intake and weight gain (Asnicar et al., 2001; Wierup et al., 2005). Heterozygous mutations in CART can lead to hereditary obesity and reduced metabolic rate (del Giudice et al., 2001). However, the receptor for CART has not yet been identified.

Peptide YY (PYY) and pancreatic polypeptide (PPY)

PYY and PPY are members of the neuropeptide Y (NPY) family, each consisting of 36 amino acids. PYY is primarily expressed in enteroendocrine L cells of the intestine, endocrine pancreas, and enteric neurons, with lower levels in the pituitary and hypothalamus (Cox, 2007; Ekblad & Sundler, 2002; McGowan & Bloom, 2004; Morimoto et al., 2008). PPY is mainly secreted by PP (F) cells in the pancreatic islets near the duodenum. Both PYY and PPY are involved in appetite regulation (Ekblad & Sundler, 2002; Kimmel, Hayden & Pollock, 1975; Larsson, Sundler & Håkanson, 1976).

PYY exists in two endogenous forms: PYY(1-36) and PYY(3-36). PYY(1-36) cannot cross the blood–brain barrier and does not affect food intake in rats lacking dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) (Unniappan et al., 2006). PYY(1-36) is cleaved by DPP4 into PYY(3-36), which can cross the blood–brain barrier (Eberlein et al., 1989; Mentlein et al., 1993; Nonaka et al., 2003), a necessary step for PYY’s anorexigenic effects (Unniappan et al., 2006). PYY(3-36) acts via the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor, which is encoded by the NPY2R gene and expressed in the ARC, NTS, and posterior hypothalamic area (Gustafson et al., 1997; Rose et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2010). Peripheral administration of PYY(3-36) reduces food intake and body weight in rodents and humans, an effect not observed in Y2 receptor knockout mice (Batterham et al., 2002). The development of long-acting PYY therapies for obesity is challenging due to suboptimal efficacy and side effects including nausea and vomiting (Gantz et al., 2007; Steinert et al., 2010).

PPY acts via the neuropeptide Y Y4 receptor, encoded by the NPY4R gene and expressed in the hypothalamus, coronary arteries, and ileum (Bard et al., 1995). Peripheral administration of PPY reduces food intake in mice and humans, but intracerebroventricular injection in mice has the opposite effect (Asakawa et al., 1999; Batterham et al., 2003). NPY4 knockout mice exhibit increased body weight and white adipose tissue accumulation (Sainsbury et al., 2002).

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is a protein encoded by the GHRL gene, processed by prohormone convertases 1 and 3 (PC1/3) and primarily secreted by the gastric oxyntic glands (Kojima et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 2006). Ghrelin is activated through acylation by ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT), which is necessary for activating its receptor, the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR) (Al Massadi, Tschöp & Tong, 2011; Kojima et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2008). GHSR is mainly expressed in the hypothalamus (particularly the ARC), pituitary, hippocampus, and posterior hypothalamic area (Bailey et al., 2000; Guan et al., 1997).

Acylated ghrelin activates GHSR to induce growth hormone (GH) release, a process independent of and more efficient than growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) (Schuetz & Markmann, 2015). Subcutaneous and intracerebroventricular administration of ghrelin in mice leads to weight gain (Tschöp, Smiley & Heiman, 2000). Some studies suggest that ghrelin acts upstream of the NPY/AgRP and POMC/CART pathways (Nakazato et al., 2001). GHRL knockout mice do not exhibit any abnormalities, whereas GHSR knockout mice show long-term weight reduction (Sun, Ahmed & Smith, 2003; Sun et al., 2004; Zigman et al., 2005). GOAT knockout mice do not exhibit abnormalities on standard or high-fat diets, but prolonged caloric restriction leads to hypoglycemia and weight loss due to GH deficiency (Zhao et al., 2010).

Data indicate that plasma ghrelin levels in humans are inversely correlated with BMI and fat mass (Tschöp et al., 2001) and that these levels increase following fasting and in anorexia nervosa (Ariyasu et al., 2001). The proportion of unacylated ghrelin increases in Prader-Willi syndrome, a typical genetic hypothalamic obesity (HyOb) disorder (Kuppens et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2011). To date, no successful trials of ghrelin receptor antagonists have resulted in weight loss in humans.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)

GLP-1 is a protein encoded by the GCG gene and produced through proteolytic cleavage by prohormone convertases 1 and 3 (PC1/3). It is one of the two incretins secreted by the gut and is a potent stimulator of insulin secretion, GLP-1 primarily released by intestinal L cells in response to nutrient intake (Kim & Egan, 2008). GLP-1 is also produced in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) (Larsen et al., 1997a; Larsen, Tang-Christensen & Jessop, 1997b). The GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) is expressed in the cerebral cortex, paraventricular nucleus (PVN), ventromedial nucleus (VMN), arcuate nucleus (ARC), and supraoptic nucleus (SON) (Alvarez et al., 2005; Larsen, Tang-Christensen & Jessop, 1997b). The action of GLP-1 is rapidly terminated by dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), which is present in the capillaries of the intestinal mucosa (Hansen et al., 1999). Studies have shown that intracerebroventricular injection of GLP-1 in rats reduces food intake (Tang-Christensen, Vrang & Larsen, 2001). Specific knockout of the GCG gene in the NTS of rats leads to increased food intake, weight gain, fat accumulation, and glucose intolerance (Barrera et al., 2011). In humans, exogenous GLP-1 reduces food intake, increases satiety, delays gastric emptying, and improves glucose tolerance, with weight loss effects demonstrated in 25 meta-analyses (Vilsbøll et al., 2012). Recently, GLP-1 receptor agonists have been approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity (Wharton et al., 2023; Wilding et al., 2021).

Cholecystokinin (CCK)

Cholecystokinin is synthesized as a prepeptide encoded by the CCK gene and then cleaved into peptides of various lengths, with CCK-33 being the predominant form in human plasma and the small intestine (Rehfeld et al., 2001). CCK is a gut peptide hormone primarily expressed in the I cells of the small intestinal mucosa, but it is also widely expressed in the central nervous system, mainly as CCK-8 (D’Agostino et al., 2016; Garfield et al., 2012; Lindefors et al., 1993; Rehfeld, 1978). The expression of different molecular forms of CCK in various tissues is predominantly controlled by the expression of different prohormone convertases (Rehfeld et al., 2008).

CCK acts through two receptors, CCKAR and CCKBR. Although CCKBR is the predominant receptor in the central nervous system (Gaudreau et al., 1983; Nishimura et al., 2015), CCKAR is believed to mediate the anorexigenic effects of CCK in the brain (D’Agostino et al., 2016; Wolkowitz et al., 1990). CCKAR is primarily found in the pancreas and stomach, with brain expression limited to the area postrema (AP) and NTS, and it is highly selective for CCK-8 (Hill et al., 1987; Moran et al., 1986; Scarpignato, Varga & Corradi, 1993). Knockout of CCKAR in OLETF rats leads to increased appetite and obesity (Funakoshi et al., 1995; Moran et al., 1998). Peripheral administration of CCK-8 has been shown to inhibit food intake (Lindén, 1989; Pi-Sunyer et al., 1982; Stacher et al., 1982), and using CCKAR antagonists increases subjective hunger in men (Wolkowitz et al., 1990).

Estrogen and androgen

Estrogens exert their effects through estrogen receptors (ERs), of which there are two types: ERα and ERβ. Estrogens act on ERα in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus to inhibit the AMPK pathway, increase UCP1 expression, and enhance thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue (BAT) (González-García, Tena-Sempere & López, 2017). Additionally, estrogens activate ERα to decrease lipoprotein lipase activity, increase β-adrenergic receptor activity, and enhance sympathetic nervous system activity, promoting the browning of white adipose tissue and increasing BAT thermogenesis (González-García, Tena-Sempere & López, 2017). Estrogens also regulate food intake via pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons (González-García, Tena-Sempere & López, 2017). Research on ERβ is less extensive compared to ERα, and the specific roles and mechanisms of ERβ in central nervous system energy metabolism require further investigation. Generally, ERβ activation is thought to improve systemic metabolism through adipose tissue function and enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis (González-Granillo et al., 2019), making ERβ a potential target for new treatments for metabolic diseases.

Androgens are generally considered to have anti-obesity effects, and reduced androgen levels can lead to obesity (Blouin, Boivin & Tchernof, 2008; O’Reilly, House & Tomlinson, 2014). Androgen receptors (ARs) are primarily expressed in visceral adipose tissue, and AR knockout mice exhibit increased body weight, reduced leptin and insulin sensitivity, and decreased BAT thermogenesis (Fan et al., 2008). Currently, there is no clear evidence that androgen can control weight in individuals with obesity with normal gonadal function. Although androgen receptor modulators such as GTX-024 have been developed for treating muscle atrophy and bone loss (Dalton et al., 2011), there is a lack of research on androgen receptor modulators specifically targeting obesity and related diseases.

Hypocretin/orexin

Hypocretin, also known as orexin, consists of two types: hypocretin-1 (orexin A) and hypocretin-2 (orexin B), both encoded by the HCRT gene. Its most well-known role is in regulating the sleep-wake cycle (Estabrooke et al., 2001; Zink, Perez-Leighton & Kotz, 2014). There are two types of hypocretin receptors, HCRTR1 and HCRTR2, with HCRTR1 being selective for hypocretin-1, while HCRTR2 is non-selective (Sakurai et al., 1998). HCRT is expressed in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), dorsomedial nucleus (DMN), and ventral thalamus, with widespread neuronal projections to areas including the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), locus coeruleus, and nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) (De Lecea et al., 1998; Hagan et al., 1999; Peyron et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 1998). It is important to note that the overall impact of the hypocretin system on appetite is not fully understood. Mice with HCRT gene ablation exhibit late-onset obesity despite reduced food intake compared to wild-type mice (Hara et al., 2001). The cortical perifornical area of the LHA is a major site for neuropeptide Y (NPY)-induced feeding, with NPY axons synapsing onto hypocretin neurons (Schwartz et al., 2000; Stanley et al., 1993). In fasting rats, HCRT expression increases while insulin decreases, and intracerebroventricular injection of both types of hypocretin promotes appetite (Sakurai et al., 1998). In humans, plasma hypocretin-1 levels are inversely correlated with BMI. Increased HCRT signaling via HCRTR2 mediates resistance to high-fat diet-induced obesity under conditions of reduced food intake and increased energy expenditure (Funato et al., 2009; Perez-Leighton et al., 2012).

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), encoded by the BDNF gene, is a widely-expressed protein in the neurotrophin family that plays a crucial role in neuronal growth and neuro-protection (Chen & Weber, 2001; Jones & Reichardt, 1990; Liu et al., 2005; Pruunsild et al., 2007; Zuccato et al., 2001). BDNF is expressed in the VMN, PVN, LHA, and anterior hypothalamus of rodents (Kernie, Liebl & Parada, 2000; Xu et al., 2003). Food intake and body weight increased over time in heterozygous BDNF mice, accompanied by the dysregulation of 5-HT (serotonin) transmission (Kernie, Liebl & Parada, 2000; Lyons et al., 1999). Intracerebroventricular injection of BDNF in these heterozygous mice resulted in significant weight loss (Kernie, Liebl & Parada, 2000). In brain-specific conditional knockout mice, baseline expressions of NPY, AgRP, CART, and LepR in the hypothalamus were unchanged, but POMC expression was increased (Rios et al., 2001). Additionally, BDNF can lower blood glucose and exert antidiabetic effects by enhancing insulin secretion and sensitivity (Nakagawa et al., 2000).

BDNF exerts its effects through the tyrosine receptor kinase B (TRKB), which is encoded by the NTRK2 gene and is widely expressed in the brain and other tissues (Luberg et al., 2010). Heterozygous mutations of NTRK2 have been identified in human obesity and developmental delay syndromes (Miller et al., 2017b; Yeo et al., 2004). NTRK2 hypomorphic mice exhibit increased appetite, fat accumulation, and obesity similar to that seen in heterozygous BDNF mice (Xu et al., 2003). Administration of an MC4R agonist during fasting increases NTRK2 expression in the VMN, suggesting that BDNF/TRKB acts downstream of the POMC/αMSH/MC4R system (Xu et al., 2003).

Nesfatin-1 and Nesfatin-1-like peptide

Nesfatin-1 is an 82-amino acid bioactive fragment derived from the cleavage of nucleobindin-2 (NUCB2) by PC enzymes and is currently the only known bioactive product of NUCB2(Barnikol-Watanabe et al., 1994; Cao, Liu & Zhou, 2013). NUCB2 is also expressed in other parts of the central nervous system and adipose tissue, as well as in ghrelin-secreting gastric mucosal cells and pancreatic cells (Ramanjaneya et al., 2010; Stengel et al., 2009; Stengel & Taché, 2013). Nesfatin-1 is present in the ARC, PVN, SON, and LHA of the rat hypothalamus. Among the processing byproducts of NUCB2, only nesfatin-1 reduces food intake and body weight in rats, while nesfatin-1 antibodies and NUCB2 antisense oligonucleotides antagonize these effects, which persists even in leptin receptor-deficient rats (Oh et al., 2006). The weight loss in rats is abolished by using the MC4R antagonist SHU9119, indicating that nesfatin-1 acts in a POMC-dependent rather than leptin-dependent manner (Oh et al., 2006). Nesfatin-1-positive neurons in the PVN and SON express oxytocin (OXT) and arginine vasopressin (AVP). In the absence of leptin action, nesfatin-1-induced oxytocin signaling in the PVN projecting to POMC neurons in the NTS may cause anorexia, an effect blocked by OXT antagonists (Kohno et al., 2008; Maejima et al., 2009; Shimizu et al., 2009). In diet-induced obese mice, peripheral administration of nesfatin-1 reduces hepatic lipid accumulation via an AMPK-mediated pathway (Yin et al., 2015). Nesfatin-1 decreases lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and inhibits the expression of PPARγ, fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), and CFD (adiponectin) mRNA in differentiated adipocytes (Tagaya et al., 2012). Nesfatin-1 is significantly reduced in the serum of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Başar et al., 2012). These findings suggest that nesfatin-1 has a potential role in regulating food intake and lipid metabolism. The receptor for nesfatin-1 has not yet been fully identified (Gan, Cerbone & Dattani, 2024; Prinz et al., 2016).

Nucleobindin-1 (NUCB1) contains the nesfatin-1-like peptide (NLP) sequence, which is also generated by PC enzyme cleavage (Nasri et al., 2024). NUCB1 and NUCB2 share a 60% sequence similarity in the mouse genome (Tulke et al., 2016), and the bioactive centers of murine NLP and nesfatin-1 have a 76% amino acid sequence similarity (Ramesh, Mohan & Unniappan, 2015). NLP is found in anatomical locations similar to nesfatin-1 (Ramesh, Mohan & Unniappan, 2015; Sundarrajan et al., 2016). It has also been shown to suppress food intake and regulate the expression of appetite-regulating hormones in goldfish and rats (Nasri et al., 2024; Sundarrajan et al., 2016) as well as reduce lipid accumulation in hepatocytes (Nasri et al., 2024).

Oxytocin

Oxytocin (OXT) is encoded by the OXT gene. It is primarily secreted by the magnocellular neurons of the supraoptic nucleus (SON) and the magnocellular and parvocellular neurons of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) in the hypothalamus(Jenkins et al., 1984; Ludwig, 1998). There is also evidence that PVN neurons can project extensively throughout the central nervous system (CNS) (Jenkins et al., 1984; Sawchenko & Swanson, 1982; Swanson & Sawchenko, 1983). Neurons expressing OXT have been found outside the hypothalamus, indicating that OXT synthesis is not restricted to the central nervous system (Amico, Finn & Haldar, 1988; Frayne & Nicholson, 1998; Furuya et al., 1995; Gimpl & Fahrenholz, 2001; Møller, 2021). The receptor for OXT, OXTR, is a single G protein-coupled receptor encoded by the OXTR gene (Kimura et al., 1992; Simmons Jr et al., 1995). OXTR is found throughout the brain, thymus, adipose tissue, kidneys, pancreas, blood vessels, and osteoblasts (Gan, Cerbone & Dattani, 2024; Gimpl & Fahrenholz, 2001; Kimura et al., 1992).

In rats, both central and peripheral administration of OXT leads to anorectic effects, which are counteracted by OXT antagonists (Arletti, Benelli & Bertolini, 1989). Intraperitoneal administration of OXT in rats increases c-fos expression in the PVN, ARC, locus coeruleus, NTS, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, and the area postrema, regulating energy metabolism (Maejima et al., 2011). OXT gene knockout mice exhibit a persistent preference for sweet and carbohydrate-containing solutions (Amico et al., 2005; Billings et al., 2006; Miedlar et al., 2007; Olszewski et al., 2010; Sclafani et al., 2007), while both OXT and OXTR gene knockout mice show increased body weight and deposition of white and brown adipose tissue (Camerino, 2009; Kasahara et al., 2013; Leng et al., 2008; Mantella et al., 2003; Nishimori et al., 2008; Takayanagi et al., 2008). Recent studies suggest that OXT may also be secreted by peripheral sympathetic nerves, with tyrosine hydroxylase-expressing sympathetic neurons being the primary source of OXT in adipose tissue. OXT enhances PKA-mediated phosphorylation events that promote lipolysis through MAPK/ERK signaling rather than via the classical cAMP/PKA cascade. Moreover, the synergistic effect of OXT with β-adrenergic agonists greatly enhances lipolysis (Li et al., 2024).

No known pathogenic human mutations of OXT and OXTR have been reported (Gan, Cerbone & Dattani, 2024). Due to OXT’s inherent instability, low molecular weight, and low concentration, it is susceptible to interference by other plasma proteins (Brandtzaeg et al., 2016; Burd et al., 1987; Gan, Cerbone & Dattani, 2024; Lawson, 2017; McCullough, Churchland & Mendez, 2013; Szeto et al., 2011), making it challenging to measure OXT concentrations in the CNS and plasma. Studies on the relationship between plasma OXT concentration and human obesity have yielded varying results, with some studies indicating higher peripheral OXT concentrations in obese subjects (Kujath et al., 2015; Schorr et al., 2017; Szulc et al., 2016), while others report the opposite (Binay et al., 2017; Eisenberg et al., 2018; Qian et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2016). Intranasal administration of OXT has been shown to reduce food intake and BMI in common obese males and decrease caloric intake in healthy males, although appetite or energy expenditure remains unchanged (Lawson et al., 2015; Thienel et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2013). However, in Prader-Willi syndrome, intranasal OXT administration does not significantly reduce food intake, body weight, or BMI (Kuppens, Donze & Hokken-Koelega, 2016; Miller et al., 2017a; Tauber et al., 2017). The pharmacokinetics of intranasal OXT administration remain unclear (Gan, Cerbone & Dattani, 2024).

Gut-brain axis in obesity

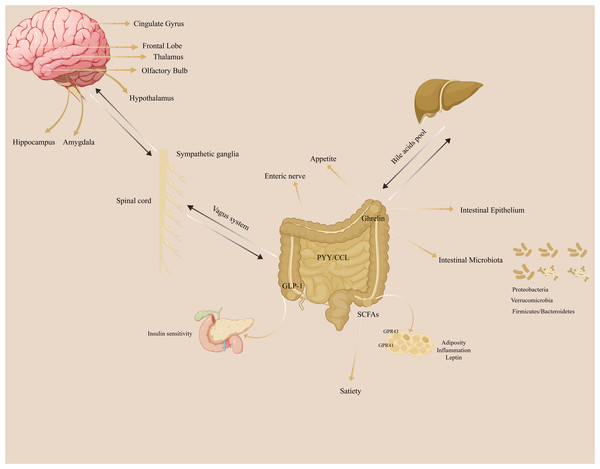

The gut-brain axis refers to the bidirectional communication network between the brain and the gut. (Fig. 1). The gut microbiota does not synthesize and secrete hormones or other substances, so it cannot be identified as a special secretory gland. However, the gut microbiota can break down food residues to produce certain substances, promote the absorption and utilization of nutrients, provide immune support, affect nerve signal transmission, and regulate other gut microbes and their host responses.

Figure 1: The illustration of gut-brain axis in the regulation of adiposity.

The gut-brain axis plays a crucial role in the adiposity.Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are metabolites produced by the fermentation of carbohydrates by certain gut microbes. They primarily consist of acetate, propionate, and butyrate and regulate intestinal pH, promote nutrient absorption, protect the intestinal mucosal barrier, and modulate mucosal immune function. Additionally, SCFAs can enter the systemic circulation and directly affect metabolism and the function of peripheral tissues (Blaak et al., 2020; Rastelli, Cani & Knauf, 2019; Régnier et al., 2021). SCFAs stimulate the secretion of peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in the gut. This activates free fatty acid receptors 2 and 3 (FFAR2 and FFAR3) to regulate immunity, inflammation, gut transit time, and metabolism, thereby promoting gut-brain axis signaling (Blaak et al., 2020; De Vos et al., 2022; Rastelli, Cani & Knauf, 2019; Régnier et al., 2021). In rodent studies, SCFAs have shown potential in preventing weight gain or aiding weight loss (Blaak et al., 2020). Although human data are limited (van Deuren, Blaak & Canfora, 2022), some studies suggest that increasing colonic propionate can regulate appetite in overweight adults and prevent weight gain, indicating that enhancing SCFA production might be an effective strategy for obesity prevention (Byrne et al., 2019; Chambers et al., 2019; Chambers et al., 2015).

Bile acids

Bile acids are the main components of bile and are released into the small intestine after eating to aid in the absorption of lipids and fat-soluble vitamins. They are considered key regulators of systemic metabolism, influencing the secretion of peptide YY (PYY), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), fibroblast growth factors, and cholesterol metabolism, as well as affecting overall energy expenditure through interactions with nuclear and membrane receptors (Tu et al., 2022). In the intestinal lumen, bile acids can be converted by gut microbes into secondary bile acids such as deoxycholic acid, lithocholic acid, and ursodeoxycholic acid (secondary in humans, primary in rodents) (Ridlon et al., 2016; Ridlon, Kang & Hylemon, 2006). A high-fat diet can increase the levels of secondary bile acids in feces and circulation (Duparc et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2019). Gut microbiota affect the enterohepatic bioavailability and bioactivity of bile acids, influencing the metabolic reactions in which they participate (De Aguiar Vallim, Tarling & Edwards, 2013). The microbiota-bile acid crosstalk is thought to contribute to weight regain after calorie restriction (Li et al., 2022a).

Tryptophan metabolites

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid used in protein synthesis and plays a key role in the microbial influence on weight and metabolism (Gao et al., 2020). Microbially produced tryptophan metabolites are involved in appetite regulation by signaling to local and distant organs (Agus, Planchais & Sokol, 2018).

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a sensor of environmental and physiological signals and a potent regulator of gut barrier integrity, immunity, and metabolism. Tryptophan metabolites such as tryptamine, indole-3-acetic acid, and 3-indolepropionic acid (IPA) are natural ligands for AhR (Natividad et al., 2018). There is evidence that IPA is secreted from the gut into the blood circulation and then targets STAT3 in the hypothalamic appetite regulation center, promoting STAT3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation and enhancing the body’s response to leptin (Wang et al., 2024b). IPA and Clostridium sporogenes supplement effectively controls weight gain, improves glucose metabolism, and reduces inflammation in DIO mice (Wang et al., 2024b). The GLP-1 receptor signaling pathway is a necessary mechanism for preventing hypothalamic inflammation and increasing leptin sensitivity (Heiss et al., 2021). A decline in the microbial production of AhR ligands can lead to reduced glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion and a compromised mucosal barrier integrity; this can potentially promote metabolic syndrome, increased BMI, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension (Natividad et al., 2018; Postal et al., 2020; Zelante et al., 2013).

Endocannabinoid system (ECS)

The endocannabinoid system (ECS) is a vast network of chemical signals and cellular receptors that are densely distributed throughout the brain and body. It regulates functions such as sleep, temperature control, inflammation, immune response, and appetite (Busquets-García, Bolaños & Marsicano, 2022; Cani et al., 2016). The ECS and other related bioactive lipids and receptors are modulated by gut microbiota (Muccioli et al., 2010). Studies show that N-acyl amide synthase genes are enriched in gastrointestinal bacteria, with the encoded lipids interacting with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Cohen et al., 2017). Additionally, the host’s ECS can regulate the composition and activity of gut microbiota, influencing fat browning, energy expenditure, and food intake through the gut-brain axis (Everard et al., 2019; Geurts et al., 2015; Rastelli et al., 2020).

Dietary influence on gut microbiota

The Mediterranean diet is widely associated with lower mortality and reduced risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, low-grade inflammation, and many other diseases (De Filippis et al., 2016; Khalili et al., 2020; Sofi et al., 2008). Metabolomic analyses have found that individuals on a Mediterranean diet have higher levels of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia and lower levels of Ruminococcus gnavus and Ruminococcus torques compared to controls (Meslier et al., 2020; Tsigalou et al., 2021). Although the exact mechanisms are not yet fully understood, current evidence suggests a significant link between gut microbiota, their metabolites, and the benefits of the Mediterranean diet (Cani & Van Hul, 2020).

Ketone bodies can improve metabolism, promote weight loss, reduce inflammation, and alleviate mental disorders (Hersant & Grossberg, 2022; Kolb et al., 2021; Puchalska & Crawford, 2017). Research over the years has demonstrated the efficacy of the ketogenic diet in promoting weight loss, though the underlying mechanisms are not completely understood. Studies indicate that ketone bodies directly affect gut microbiota, with Bifidobacteria (particularly Bifidobacteria adolescentis) being most reduced on a ketogenic diet compared to a standard diet; this reduction is associated with decreased inflammation (Ang et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2020). The ketogenic diet may lack beneficial fibers and polyphenols from fruits and grains, potentially leading to long-term adverse metabolic effects such as glucose intolerance and lipid abnormalities (Ellenbroek et al., 2014). Individuals on a ketogenic diet are advised to increase biotin intake (Van Hul & Cani, 2023; Yuasa et al., 2013).

Past studies have shown that gut microbiota transplantation can successfully improve insulin sensitivity in obese patients and gradually normalize metabolic levels (Vrieze et al., 2012). However, microbiota transplantation cannot improve insulin sensitivity in individuals with type 2 diabetes and high insulin resistance (Gómez-Pérez et al., 2024). There are also many studies indicating that gut microbiota transplantation does not reduce the weight of obese patients (Allegretti et al., 2020; Lahtinen et al., 2022; Leong et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Daily supplementation of low fermentation fiber as an adjuvant therapy for fecal microbiota transplantation can enhance insulin sensitivity and increase levels of beneficial gut microbiota in obese patients (Mocanu et al., 2021). Although the safety of gut microbiota transplantation has been confirmed, further research is needed on how to more effectively improve the metabolic levels and weight of obese patients.

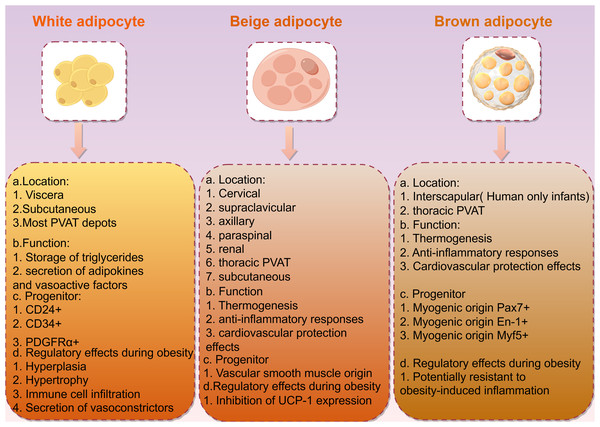

Anti-obesity therapeutic approaches developed by targeting neuroendocrine systems

Obesity is closely associated with adipose tissue, which in mammals is primarily divided into two types: white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT; Fig. 2). White adipose tissue is the most abundant type of adipose tissue and serves as an energy storage depot, while brown adipose tissue is involved in thermogenesis, converting energy into heat through uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). UCP1 is a member of the mitochondrial anionic carrier protein (MACP) family. It is mainly found in the transmembrane region, inner membrane, and matrix of BAT mitochondria, and has the function of transporting fatty acid anions. ATP can enter UCP1 molecules from both sides of the mitochondrial membrane and decouple with the central site, catalyzing the downward transport of protons along the concentration gradient. This eliminates the transmembrane proton concentration difference on both sides of the mitochondrial inner membrane, slowing down the oxidative phosphorylation process driven by the proton concentration difference. This, in turn, promotes the continuous reflux of protons in the mitochondrial inner membrane and leads to oxidative phosphorylation entering an idle state, causing BAT to produce heat dependent on UCP1, but not ATP, hindering ATP production (Lu et al., 2019). If the central site of UCP1 is occupied by ADP or AMP, it inhibits the occurrence of decoupling (Huang, Lin & Klingenberg, 1998). BAT mitochondria rely on UCP1 for thermogenesis, resulting in a relative decrease in ATP production and the promotion of energy metabolism in the body. Glucose is supplemented with ATP through aerobic glycolysis to compensate for both the reduced ATP production caused by UCP1 uncoupling and the oxidative phosphorylation in BAT mitochondria (Leu et al., 2018). Additionally, BAT exhibits autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine functions, playing a role in energy and temperature regulation by interacting with other metabolic tissues. White adipocytes can undergo browning, transforming into brown adipocytes in response to external stimuli such as exercise and cold exposure (Shamsi, Wang & Tseng, 2021). This browning process presents a novel approach for obesity treatment.

Figure 2: Description and characteristics of different types of adipocytes including locations, functions, and progenitors.

The influence of hormones, growth factors, and transcription factors on adipose tissue browning

Research indicates that various hormones, including thyroid hormone (Johann et al., 2019), insulin (Homan et al., 2021), prostaglandins (Kajimura & Saito, 2014), irisin (Bao et al., 2022), and estrogen (Santos et al., 2018), can promote the browning of white adipose tissue. Recent studies have also uncovered new findings regarding hormonal influences on adipose tissue conversion. Elevated serum parathyroid hormone levels can promote WAT browning, leading to weight loss in mice with primary hyperparathyroidism (He et al., 2019). Metabolomic analyses have identified three small-molecule metabolic hormones—3-methyl-2-oxopentanoic acid, 5-oxopentanoic acid, and β-hydroxyisobutyric acid—that can induce the conversion of WAT to BAT while enhancing mitochondrial oxidative energy metabolism in muscle tissue (Whitehead et al., 2021).

Beyond hormones, fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) activates BAT and promotes WAT browning, reducing atherosclerosis and improving hyperlipidemia (Abu-Odeh et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) regulate the formation and thermogenic activity of brown fat, with BMP-7, BMP8bβ, and BMP9 promoting the browning of white fat (Choi & Yu, 2021; Harms & Seale, 2013; Um et al., 2022). Cold exposure enhances the phosphorylation of the transcription factor SOX4 via the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway, promoting its nuclear translocation and enhancing EBF2 transcription, which together activate a transcriptional program controlling thermogenic gene expression (Wang et al., 2025). PRDM16 is a crucial transcription factor in brown adipocyte differentiation, which is essential for maintaining the unique morphological characteristics and cellular functions of brown adipocytes (Iida et al., 2015; Kajimura et al., 2009). Recent studies suggest that PRDM16 and the fatty acid transporter FATP1 may serve as key mediators of sympathetic nerve-induced WAT browning as well as potential molecular targets for drug-induced WAT browning (Guo et al., 2022). BCA2 is a key enzyme in branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism; when BCA2 is knocked out in adipose tissue, it results in decreased acetylation of PRDM16, thereby enhancing the interaction between PRDM16 and PPARγ and promoting WAT browning. Further drug screening revealed that telmisartan directly binds BCAT2 to inhibit BCAA metabolism, counteracting high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice (Ma et al., 2022). The GABAergic neurons in the DMH may be important neuronal populations that predominantly regulate adipose browning, and the enzymatic subtype -conversion of PKA induced by RIIβ gene knockout may be a crucial event for eliciting WAT browning of RIIβ-KO mice (Wang et al., 2023). Moreover, recent findings indicate that the adipocyte β-AR (β-adrenergic receptor)-mTOR-Lipin1 axis mediates sympathetic nervous excitation that leads to adipose tissue browning. Analysis of human clinical data and public medical transcriptome sequencing data revealed a negative correlation between mTOR and Lipin1 expression levels in adipose tissue and BMI, highlighting the potential significance of mTOR and Lipin1 in human obesity and treatment (Wang et al., 2024a).

The influence of gut microbiota on adipose tissue browning

Research on the relationship between human gut microbiota and adipose tissue browning is relatively limited. Gut microbiota plays an important regulatory role in thermogenesis in cold environments. In cold conditions, the Firmicutes family Ruminococcaceae increases in individuals with obesity, correlating with elevated plasma acetate levels (Zietak et al., 2016). Other studies have found that acetate can enhance brown adipose tissue activity and induce WAT browning (Hu et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2016; Sahuri-Arisoylu et al., 2016; Weitkunat et al., 2017). UCP1-dependent thermogenesis is impaired in antibiotic-treated or germ-free mouse models but can be partially restored with butyrate gavage (Li et al., 2019). Additionally, supplementation with butyrate-producing bacteria in mice partially alleviated diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance, WAT hypertrophy, and inflammation (Le Roy et al., 2022).

Factors affecting WAT browning are not limited to those mentioned above. Studies have shown that β3-AR agonists, GLP-1 receptor agonists, AMPK agonists, and PPARs agonists can induce adipocyte browning (Baskaran et al., 2016; Collier et al., 2021; Ohno et al., 2012; Pan & Chen, 2022; Rachid et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2016). Nicotine induces WAT browning through κ-opioid receptors (KOR) (Seoane-Collazo et al., 2019). Leucine deficiency can also induce WAT browning (Yuan et al., 2020). The synthesis and degradation of glycogen are necessary for adipocyte browning. The synthesis and conversion of glycogen ensure that only white adipocytes have sufficient energy to provide thermogenic fuel, thereby preventing the potential toxic effects of ATP uncoupling caused by UCP1 expression (Keinan et al., 2021). Glycogen synthesis and degradation are increased in response to catecholamines, and glycogen turnover is required to produce reactive oxygen species leading to the activation of p38 MAPK, which then drives UCP1 expression (Keinan et al., 2021). In addition to cold stimulation, beige fat can induce local mild heat effects and activate thermogenesis through HSF1. Thermogenesis can safely and effectively resist and treat obesity and decrease metabolic disorder symptoms, such as insulin resistance and liver lipid deposition in mice (Li et al., 2022b). Beyond obesity, BAT activation is an effective strategy for treating hyperlipidemia and preventing atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, and hypertension (Becher et al., 2021; Doukbi et al., 2022; Roth, Molica & Kwak, 2021). It should be noted that the potential for WAT browning may be lower in humans than in mice (Comas et al., 2019; Moreno-Navarrete & Fernandez-Real, 2019).

Potential issues and risks of WAT browning

The process of WAT browning is not without potential issues and risks. The conversion from WAT to BAT increases energy expenditure associated with cancer-related cachexia. WAT browning is linked to increased expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), which uncouples mitochondrial respiration to produce heat, leading to enhanced fat mobilization and energy expenditure in cachectic mice (Petruzzelli et al., 2014). Additionally, the inflammatory response involved in BAT activation and WAT browning is a potential issue (Anderson et al., 2022). Adipose tissue is not merely an energy reservoir but also participates in immune regulation. Excessive inflammatory responses may lead to insulin resistance and other metabolic disorders, potentially dysregulating immune function. It is important to note that most agonists activating brown adipose tissue function through β3-adrenergic receptor signaling, which can cause vasoconstriction and increased blood pressure, potentially imposing additional burdens on the cardiovascular system (Gaspar et al., 2021). At the molecular level, the browning process involves complex transcriptional networks and signaling pathways, which, if imbalanced, may lead to cellular stress responses and programmed cell death. Furthermore, certain transcription factors and activators may induce DNA damage while increasing fat oxidation, thereby affecting cellular genomic stability.

WAT browning observed in animal models may not necessarily apply to humans. This discrepancy could be due to the stricter control of conditions and the uniform genetic background of subjects used in animal studies, whereas human studies must consider a broader range of genetic and environmental factors. In conclusion, through an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms underlying WAT to BAT browning, researchers can develop new drugs, nutritional interventions, and lifestyle modifications to ensure the safety and efficacy of the browning process under low-risk conditions. This approach plays a crucial role in the treatment and prevention of obesity and metabolic diseases, thereby contributing to human health and well-being.

| Category | Specific hormone/pathway | Core effect on obesity | Key regulatory mechanism | Existing challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine hormones | Thyroid Hormones (T3/T4) | Inhibits obesity (promotes thermogenesis, lipid metabolism) | T3 promotes BAT thermogenesis via TRα; TRβ regulates adipocyte differentiation and inhibits HFD-induced obesity | Systemic thyroid dysfunction must be avoided; Human BAT is less sensitive to T3 than mouse BAT |

| Leptin | Inhibits obesity (suppresses appetite, regulates energy) | Binds to LepR to activate the JAK2-STAT3 pathway, downregulates AgRP/NPY, upregulates POMC, and inhibits appetite; Inhibits hypothalamic AMPK | Mechanisms of leptin resistance are not fully clarified; Blood–brain barrier (BBB) transport impairment affects efficacy | |

| Insulin | Inhibits obesity (synergizes with leptin to regulate appetite) | Binds to INSR to activate the PI3K-AKT-Foxo1 pathway, upregulates POMC, and inhibits feeding; Regulates fat deposition in adipocytes | Insulin resistance varies significantly across tissues (brain/adipose/liver); Targeting specificity is difficult to control | |

| POMC/αMSH/CART | Inhibits obesity (potently suppresses appetite) | POMC is cleaved into αMSH, which regulates appetite via MC4R; CART synergizes with POMC to inhibit feeding | CART receptor has not been identified; MC4R agonists may cause cardiovascular side effects | |

| PYY/PPY | Inhibits obesity (suppresses appetite) | PYY(3-36) binds to Y2R and PPY binds to Y4R to downregulate hypothalamic appetite signals | PYY(1-36) cannot cross the BBB; Central injection of PYY promotes appetite (contradictory mechanism) | |

| Ghrelin | Promotes obesity (stimulates appetite, increases weight) | Acylated ghrelin binds to GHSR, activates the NPY/AgRP pathway, promotes feeding, and inhibits BAT thermogenesis | GHSR antagonists have not succeeded in human weight loss trials; Bidirectional regulatory effects of ghrelin on metabolism are unclear | |

| Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) | Inhibits obesity (reduces feeding, controls blood glucose) | Binds to GLP-1R, delays gastric emptying, promotes insulin secretion, and activates hypothalamic satiety signals | Long-term use may increase the risk of thyroid C-cell tumors; Injectable administration limits adherence | |

| Cholecystokinin (CCK) | Inhibits obesity (suppresses appetite, promotes satiety) | CCK-8 binds to CCKAR, activates NTS satiety signals, and inhibits gastric emptying | CCK has a short duration of action (requires continuous administration); The association between central CCKBR function and obesity is unclear | |

| Estrogen/Androgen | Estrogen inhibits obesity; Androgen resists obesity | Estrogen promotes BAT thermogenesis and WAT browning via ERα; Androgen reduces fat accumulation via AR | Estrogen modulators may increase breast/uterine cancer risk; Androgens are ineffective for weight loss in individuals with normal gonadal function | |

| Hypocretin/Orexin | Bidirectional regulation (promotes appetite/resists obesity) | Activation of HCRTR2 promotes energy expenditure; HCRTR1 is involved in appetite regulation | Complex systemic effects may disrupt the sleep-wake cycle; Bidirectional regulatory mechanisms are not fully resolved | |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) | Inhibits obesity (reduces feeding, controls metabolism) | Binds to TRKB, downregulates AgRP, upregulates POMC, and enhances insulin sensitivity | BDNF cannot cross the BBB; Peripheral administration easily causes neurotoxicity | |

| Nesfatin-1/NLP | Inhibits obesity (reduces feeding, suppresses fat accumulation) | Nesfatin-1 acts via the POMC/MC4R pathway; NLP inhibits appetite and reduces hepatic lipids | Nesfatin-1/NLP receptors have not been identified; Metabolic regulatory effects in humans are unvalidated | |

| Oxytocin (OXT) | Inhibits obesity (reduces feeding, promotes lipolysis) | Binds to OXTR, activates PVN satiety signals, and promotes adipocyte lipolysis via the MAPK/ERK pathway | OXT is easily interfered with by plasma proteins (detection difficulties); Pharmacokinetics of intranasal administration are unclear | |

| Gut-brain axis-related pathways | Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Inhibits obesity (regulates appetite, promotes thermogenesis) | Activates FFAR2/3, promotes PYY/GLP-1 secretion, and enhances BAT activity/WAT browning | Large individual differences in human SCFA levels; Intestinal absorption efficiency affects efficacy |

| Bile acids | Bidirectional regulation (controls metabolism/promotes obesity) | Regulates GLP-1/FGF secretion; Gut microbiota convert bile acids to secondary bile acids (affecting lipid metabolism) | Excessive secondary bile acids may cause liver injury; Insufficient receptor selectivity causes systemic side effects | |

| Tryptophan Mmetabolites (e.g., IPA) | Inhibits obesity (enhances leptin sensitivity, controls glucose) | IPA activates AhR, promotes hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation, enhances GLP-1 secretion, and improves intestinal barrier function | Complex interactions among tryptophan metabolites; Large differences in gut microbiota synthesis efficiency in humans | |

| Endocannabinoid system (ECS) | Promotes obesity (stimulates appetite, inhibits lipolysis) | Gut microbiota regulate ECS activity; ECS activation promotes feeding and inhibits BAT thermogenesis | Systemic ECS inhibitors easily cause psychiatric side effects; Synergistic regulation between intestinal and central ECS is unclear | |

| WAT browning-related pathways | Thyroid hormone/GLP-1/β3-AR pathway | Inhibits obesity (promotes WAT browning) | Thyroid hormones activate UCP1; GLP-1 enhances BAT activity; β3-AR activates the cAMP-PKA pathway (promoting brown adipogenic gene expression) | Human WAT has much lower browning potential than mouse WAT; Long-term activation may cause mitochondrial oxidative stress |

| PRDM16/FATP1 pathway | Inhibits obesity (regulates BAT differentiation, WAT browning) | PRDM16 maintains BAT characteristics; FATP1 mediates sympathetic nerve-induced WAT browning | Complex PRDM16 regulatory networks may affect other cell functions; Targeted delivery to human adipocytes is difficult |

The regulatory effects and therapeutic relevance of the neuroendocrine system and gut-brain axis-related hormones/pathways on obesity have been summarized in Table 2.

Conclusions

This review focuses on the key hormones, pathways, and mechanisms that regulate adipose metabolism and contribute to the development of obesity. Regulating endocrine hormone levels to control body weight may be an effective strategy; however, most current studies assessing the impact of endocrine hormones on obesity have small sample sizes and short follow-up durations. Furthermore, some hormones, as well as related hormone receptor antagonists or agonists, not only fail to demonstrate significant efficacy but may also be accompanied by multiple side effects (e.g., nausea induced by GLP-1 agonists and thyroid dysfunction caused by thyroid hormone analogs). Environmental factors (e.g., diet, living environment) exert a significant impact on the regulation of gut microbiota. Therefore, dietary interventions, supplementation with probiotics/prebiotics/biotin, or the use of drugs that restore the diversity and normal function of gut microbiota may serve as important approaches to improving metabolism.Although the conversion of white adipose tissue to brown adipose tissue (BAT) holds therapeutic potential for metabolic-related diseases, it is essential to focus on the practical efficacy of this strategy in clinical treatment, the side effects of long-term pharmacotherapy, and the potential disorders of lipid metabolism (e.g., mitochondrial oxidative stress) that may be triggered by excessive or inappropriate activation of browning. All these issues could affect cellular homeostasis and organ function.

Future studies need to further identify unknown hormone receptors, clarify the precise signaling pathways of the gut-brain axis, reduce research discrepancies between animal studies and human studies, evaluate the long-term safety of browning strategies, and develop precision intervention tools for gut microbiota. Only through these efforts can the safe application of neuroendocrine and gut-brain axis-targeted therapies in clinical practice for obesity be promoted, thereby providing more effective solutions for the prevention and treatment of obesity and metabolic diseases.