Microbiome shifts during Fusarium oxysporum and F. solani (syn. Neocosmospora solani)—induced Ligusticum chuanxiong root rot: endophtic bacterial protective responses and fungal pathogenic tendencies

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Rodrigo Nunes-da-Fonseca

- Subject Areas

- Agricultural Science, Biodiversity, Ecology, Microbiology, Plant Science

- Keywords

- Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort., Plant microbiome, Microbiome shifts, High-throughput sequencing, Root rot

- Copyright

- © 2025 Gao et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Microbiome shifts during Fusarium oxysporum and F. solani (syn. Neocosmospora solani)—induced Ligusticum chuanxiong root rot: endophtic bacterial protective responses and fungal pathogenic tendencies. PeerJ 13:e20369 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20369

Abstract

Root rot disease is a globally significant threat to the health of diverse economically important crops. Understanding shifts in the plant microbiome during disease progression can aid in identifying beneficial microbes with disease-resistant potential and developing ecofriendly biocontrol strategies. However, microbiome changes during root rot progression in the medicinal plant Ligusticum chuanxiong remain poorly understood. This study aimed to investigate the response of host-associated microbiomes to pathogen stress (Fusarium oxysporum and F. solani syn. Neocosmospora solani) during L. chuanxiong root rot. The diversity, composition, function, and network interactions of bacterial and fungal communities were examined using high-throughput sequencing and network analysis in healthy rhizomes, healthy layers of diseased rhizomes, rotten layers of diseased rhizomes, and rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soils. The bacterial diversity decreased as root rot progressed in end ophytic (from 0.72 to 0.38) and rhizosphere soils (from 0.80 to 0.68), whereas the fungal diversity showed no significant changes. The diseased samples were enriched with root rot pathogens and other potential pathogens, such as the soil bacterium Pectobacterium and the soil fungus Gibberella, whereas beneficial taxa, including endophytic Bacillus and Trichoderma, and soil-dwelling Candidatus_Solibacter and Beauveria, were significantly reduced. Notably, in the healthy layers of diseased rhizomes, which represent a “transitional phase”, fungal communities resembled those in rotten tissues with increased pathogenic taxa (e.g., Ceratocystis and Plectosphaerella), whereas bacterial communities were more similar to healthy rhizomes and enriched in beneficial genera (e.g., Microbacterium and Variovorax). Functional prediction indicated suppressed bacterial activity and enhanced fungal saprotrophy in rotten rhizomes. The cross-kingdom network complexity decreased in both endophytic and soil microbial communities during root rot, while positive correlations within endophytic networks increased. Overall, as root rot progresses, the stability and competitive interactions within endophytic and soil microbiomes of L. chuanxiong weaken. Early in infection, endophytic bacterial and fungal communities exhibit divergent responses: bacteria likely contribute to disease resistance, whereas fungi may promote pathogenesis. This findings suggest that a more beneficial role for endophytic bacteria in controlling L. chuanxiong root rot. Restoring microbial community complexity may offer a viable biocontrol strategy. Our findings provide a theoretical foundation for future identification of specific beneficial microbes and the development of safe biocontrol approaches.

Introduction

Root rot is a soil-borne disease that causes necrosis and decay of underground plant parts, posing a serious threat to the cultivation of many economically important crops worldwide. In soybeans, root rot can reduce yields by 25% to 75%, severely impacting global food security (Qian et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2020). With the growing demand for medicinal plants in both traditional and modern pharmaceutical industries, the scale of medicinal plant cultivation has expanded substantially. However, medicinal plants are primarily root and rhizome herbs and require longer growth cycles, making them particularly vulnerable to root rot. This disease not only disrupts normal plant growth but also jeopardizes the accumulation of medicinal compounds, such as ginsenosides in Panax ginseng (Araliaceae) and triterpenoid saponins with flavonoids in Astragalus membranaceus (Fabaceae) (Han et al., 2025). Although chemical pesticides remain a primary control method, their use often leads to adverse effects such as pesticide resistance and residue accumulation. In contrast, biological control offers an environmentally friendly and sustainable alternative and has been widely explored for managing root rot in soybean, cotton, aconitum, and other crops (Sun et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024a; Babu et al., 2015).

The plant microbiome plays a vital role in plant health by promoting growth, increasing productivity, and defending against pathogens (Hu et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 0000). Healthy plant microbiomes contain diverse “disease-preventing members” that balance the ecosystem by suppressing pathogens and preventing infections (Lv et al., 2023). However, reduced microbial diversity and weakened connectivity can increase plant susceptibility to disease, as synergistic interactions among pathogens disrupt plant-microbe homeostasis and accelerate disease progression (Koskella et al., 2017; Pitlik & Koren, 2017). Interestingly, disease-induced shifts in the plant microbiome may also contribute to pathogen resistance. Certain beneficial microbes can prime systemic immunity in host plants, thereby enhancing disease resilience (Yu et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022). Therefore, identifying key microbial taxa involved in disease development is crucial for designing novel biocontrol agents and implementing sustainable plant protection strategies.

Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. is a historically important medicinal and edible plant, widely used in traditional medicine for its effective headache treatment (Committee, 2020). Modern studies have revealed that its rhizomes are rich in bioactive compounds, including phthalides, phenolic acids, alkaloids, and polysaccharides, which play crucial roles in managing cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (Wang et al., 2025; Xing et al., 2024). In some Asian countries, its leaves are also consumed as salad greens or cooked vegetables, valued for their ability to alleviate dizziness (Chen et al., 2018). However, root rot poses a serious threat to L. chuanxiong cultivation, often causing significant yield loss or complete crop failure. The primary pathogens, Fusarium oxysporum and F. solani—the latter belonging to the Fusarium solani species complex, which has been proposed as a separate genus, Neocosmospora (Lombard et al., 2015)—are soil-borne fungi that infect the root system (including the rhizome) and, under warm and humid conditions, spread to the rhizomes, leading to extensive tissue decay (Li et al., 2015; Li, 2016). Disease progression is typically accompanied by shifts in the plant’s microbial community, resulting in distinct microbial assemblages at early, middle, and late infection stages (Bass et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2017). Although pathogens drive disease development, plants actively recruit beneficial microbes to alleviate stress. Understanding these microbial dynamics during infection could reveal how the plant microbiome contributes to disease resistance and facilitate the identification of protective taxa. Harnessing such beneficial microbes to reshape the plant microecosystem offers a promising, sustainable strategy to promote plant health and mitigate disease.

The current understanding of microbiome dynamics during L. chuanxiong root rot progression remains limited. To advance knowledge in this area, we applied high-throughput sequencing to characterize bacterial and fungal microbiome shifts across three distinct disease stages: healthy, transitional (early infection), and decayed (advanced rot). By systematically analyzing diversity, structure, function, species composition, and network interactions, we revealed how the endophytic and soil microbiomes respond to pathogen stress. This study provides a theoretical basis for developing biocontrol agents against root rot and offers strategies to reduce chemical pesticide use in L. chuanxiong cultivation.

Materials and Methods

Pathogen materials and inoculation procedure

The pathogens Fusarium solani (Neocosmospora) (GenBank No. KJ573076) and F. oxysporum (GenBank No. JN232136) were originally isolated from symptomatic L. chuanxiong rhizomes collected from a field plot in Shiyang Town, Sichuan Province (Li et al., 2015).

For inoculum preparation, both species were cultured separately on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium at 28 °C until sporulation. Spore suspensions were adjusted to 105 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/mL in sterile water and mixed in equal volumes. Tissue-cultured L. chuanxiong seedlings were aseptically propagated through young stem nodal segment callusing (20∼40 days), shoot multiplication (25∼30 days), and root induction (25∼30 days), then transplanted into sterilized 4:1 nutrient soil:vermiculite (double-autoclaved at 121 °C for 90 min) and maintained under controlled conditions (25 °C, 14-h photoperiod, 6000 lux, 60% moisture). The experiment included eight replicates per treatment, with 5 mL of mixed spore suspension or sterile water (control) applied to each root zone (Li et al., 2015). Disease incidence was assessed at 14 days post-inoculation, following established criteria (Li, 2016), whereby rhizomes exhibiting no brown discoloration were classified as healthy, and those presenting brown lesions, tissue rotting, or hollow cavities were classified as diseased. To confirm Koch’s postulates, fungi were re-isolated from symptomatic tissues and morphologically verified against the original inoculum strains.

Field Sample collection and preparation

The sampling was conducted in Shiyang town, Dujiangyan city, Sichuan Province (103°39′E, 30°50′N; Southwest China), which is the core geo-authentic production region of Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. The sampling area experiences a typical humid subtropical monsoon climate, with an annual mean temperature of 17.1 °C, annual mean precipitation of 89 mm, a frost-free period of 269 days, and an annual sunshine duration of 1,034.6 h (Fang et al., 2020). Sampling was performed in mid-May 2023, coinciding with the rhizome enlargement growth stage of L. chuanxiong. In May, the mean daytime temperature is 26 °C, and the monthly rainfall reaches 95 mm. During this period, Sichuan experienced hot and rainy weather, leading to increased soil temperature and moisture, which coincided with the peak of L. chuanxiong root rot (Li, 2016).

Plant samples

Plant samples were collected using an equidistant sampling method, with four healthy L. chuanxiong plants randomly excavated from the sample field. The diseased plants were identified based on the basis of symptoms, and four symptomatic individuals were selected from the same field. The diseased plants exhibited stunted growth, with chlorotic and yellowing leaves, and the underground rhizomes showed internal browning and spongy soft rot, accompanied by a distinct sour odor. These symptoms are consistent with a wet rot pathology and align with the typical field manifestations of root rot (Li, 2016). Notably, residual healthy tissue, free from browning or decay, was observed within affected rhizomes. All plant samples were immediately transported to the laboratory, where the aboveground tissues and fibrous roots were removed, retaining only the rhizomes. Surface sterilization was performed by rinsing under running water, followed by immersion in 75% ethanol for 30 s and 5% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, and then three washes with sterile water. A sterility check was included by plating the final rinse water onto Luria Bertani (LB) agar, on which no microbial growth was observed (Fig. S1). Finally, the rhizomes were longitudinally dissected under aseptic conditions in a laminar flow hood (Sahu et al., 2022; He et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2025).

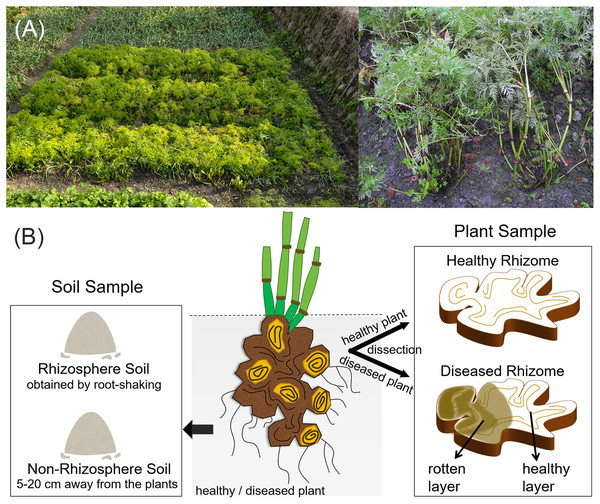

Three distinct tissue types were subsequently collected (Fig. 1): healthy rhizome (HR) samples were taken from healthy L. chuanxiong plants, with each piece including both the cortex and xylem. From diseased plants, we stratified samples into two subtypes based on pathological severity, representing different stages of infection. The diseased rhizome–healthy layer (DRH) comprises the outer, visibly non-lesioned tissue adjacent to decayed regions, reflecting early-stage infection. The diseased rhizome–rot layer (DRR) comprises the inner, fully decayed tissue, representing an advanced-stage infection that manifests wet rot pathology. All samples were placed in sterile tubes and stored at −20 °C for DNA extraction. There were four replicates per treatment (one replicate per individual plant).

Figure 1: Field condition and experimental sample types of L. chuanxiong.

(A) The field condition; (B) Representative sample types collected.Soil samples

Concurrently with plant sampling, rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soils were collected (Fig. 1). Four healthy rhizosphere soil (HS) samples and four diseased rhizosphere soil (DS) samples were obtained using the root-shaking method (Wang et al., 2024b). After removing debris and homogenizing, the samples were placed in sterile tubes, and promptly stored at −20 °C for DNA extraction. Healthy non-rhizosphere soil (HGS) and diseased non-rhizosphere soil (DGS) samples were collected five cm to 20 cm away from the plants, and were processed following the same procedure as the rhizosphere soils. There were four replicates per treatment.

DNA extraction

The collected rhizome and soil samples were pulverized with liquid nitrogen, yielding approximately 0.1 g of each sample powder for DNA extraction using the Plant DNA Isolation Kit (DE-06111, Chengdu Forgene Co., Ltd.) and Soil DNA Isolation Kit (DE-055133, Chengdu Fujibiotech Co., Ltd.). The integrity, purity, and concentration of the extracted DNA were assessed by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis (DYY-6D, Beijing Liuyi Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and a nucleic acid micro-spectrophotometer (DS-11+, Denovix, China). Qualified samples were subjected to high-throughput sequencing at Shanghai Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. Detailed sample information is provided in Table 1.

| Sample type | Sample source | Sample number | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy samples | Healthy rhizome | HR1 | HR2 | HR3 | HR4 |

| Healthy rhizosphere soil | HS1 | HS2 | HS3 | HS4 | |

| Healthy non-rhizosphere soil | HGS1 | HGS2 | HGS3 | HGS4 | |

| Diseased samples | Diseased rhizome–healthy layer | DRH1 | DRH2 | DRH3 | DRH4 |

| Diseased rhizome–rot layer | DRR1 | DRR2 | DRR3 | DRR4 | |

| Diseased rhizosphere soil | DS1 | DS2 | DS3 | DS4 | |

| Diseased non-rhizosphere soil | DGS1 | DGS2 | DGS3 | DGS4 | |

PCR amplification and high-throughput sequencing

Fungi

The fungal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region was amplified using primer pair ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS2R (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′). Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in 20 μL volumes containing two μL of 10 × Buffer, two μL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 μL of each primer, 0.2 μL rTaq polymerase, 0.2 μL of BSA, and approximately 10 ng of template DNA, with ddH2O added to reach the final volume. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; and followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Each sample was amplified in triplicate, and PCR products were pooled and verified by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Qualified amplicons were recovered and quantified using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Scientific). Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq™ DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina) and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform.

Bacteria

The bacterial 16S rDNA V5-V7 region was amplified using a two-step PCR approach to minimize host DNA amplification. Primary amplification was performed with the primers 799F (5′-AACMGGATTAGATACCCKG-3′) and 1392R (5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTRC-3′), followed by nested PCR with 799F and 1193R (5′-ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC-3′). Each 20 µL PCR reaction volume contained 2.0 µL of 10 × PCR buffer, 2.0 µL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 µL each of forward and reverse primer, 0.2 µL of rTaq polymerase, 0.2 µL of BSA, 10 ng of template DNA, and ddH2O to volume. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The first PCR consisted of 27 cycles, and the second PCR consisted of 13 cycles. The second-round PCR products were then quantified, prepared for library construction, and sequenced as described for fungal sequencing.

Statistical analysis

DNA fragments were sequenced using paired-end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. The raw sequences were processed using QIIME (v1.9.1; http://qiime.org/) for quality control and filtering. The paired-end reads from each sample were assembled using FLASH (v1.2.11; https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/FLASH/index.shtml). Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) were clustered at a 97% similarity threshold using UPARSE (v11; https://drive5.com/uparse/). OTUs were taxonomically classified using the Bayesian RDP classifier algorithm (v2.13; https://john-quensen.com/classifying/rdp-classifier-updated/), referencing the Silva database for bacteria (v138; https://www.arb-silva.de/) and the Unite database for fungi (v8.0; http://unite.ut.ee/index.php), respectively. Bioinformatic analyses were conducted on the Shanghai Majorbio Cloud Platform (http://www.majorbio.com) following the Mothur pipeline (v1.30.2; https://mothur.org/) with recommended parameters (Caporaso et al., 2010).

Results

Pathogenicity of Fusarium solani (Neocosmospora) and F. oxysporum co-infection in L. chuanxiong seedlings

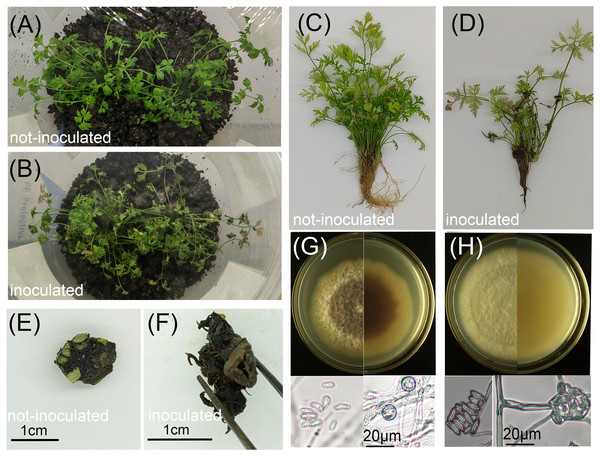

Pathogenicity tests revealed that co-inoculation with F. solani and F. oxysporum resulted in 100% disease incidence by 14 days post-inoculation, while control plants remained symptom-free (Fig. 2). Infected plants displayed stunted growth, leaf chlorosis, wilting, and reduced shoot formation compared to healthy controls (Figs. 2A–2D). Belowground, roots exhibited brown discoloration, tissue softening, and water-soaking lesions (Fig. 2D). Healthy rhizomes remained firm, displayed green stem scars, and released an aromatic odor upon cutting (Fig. 2E). In contrast, diseased rhizomes showed tissue softening, disintegration of vascular bundles leading to hollow cavities, and loss of characteristic aroma (Fig. 2F). Fungal isolates morphologically identical to the original inoculum strains were re-isolated from symptomatic tissues (Figs. 2G, 2H, Fig. S2), fulfilling Koch’s postulates and confirming F. solani and F. oxysporum as causal agents of root rot in L. chuanxiong.

Figure 2: Effects of pathogen inoculation (Fusarium solani and F. oxysporum) on L. chuanxiong seedlings.

(A, C) Healthy control seedlings without pathogen inoculation; (B, D) Diseased seedlings after pathogen inoculation; (E) Healthy rhizome from a control seedling; (F) Diseased rhizome from an infected seedling; (G, H) Front and reverse colony morphology and conidia of re-isolated pathogens: F. oxysporum (G) and F. solani (H).Analysis of the Illumina sequencing data

Microbial high-throughput sequencing was performed on three types of L. chuanxiong rhizome samples, representing distinct disease stages: healthy rhizome (healthy stage), healthy layer of diseased rhizome (transitional stage), and rot layer of diseased rhizome (decayed stage). Sequencing was also performed on soil samples collected from both healthy and diseased plants. After quality control, a total of 2,066,316 high-quality bacterial sequences (average length 376 bp) and 2,300,714 high-quality fungal sequences (average length 236 bp) were obtained. Clustering analysis identified 12,115 bacterial OTUs and 2,544 fungal OTUs. The saturation of rarefaction curves indicated sufficient sequencing depth (Fig. S3). Taxonomic annotation revealed that the bacterial communities spanned 38 phyla, 116 classes, 282 orders, 506 families, 1,124 genera and 2,318 species, while fungal communities comprised 12 phyla, 44 classes, 110 orders, 257 families, 557 genera and 904 species.

Analysis of microbial community diversity, structure, and functional characteristics during L. chuanxiong root rot progression

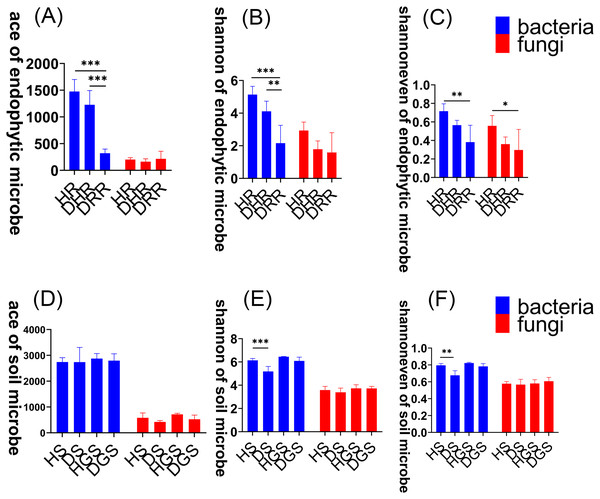

To assess changes in microbial community diversity during L. chuanxiong root rot progression, we analyzed alpha diversity across three disease stages (healthy, transitional, and decayed) using Kruskal–Wallis tests (Fig. 3, Table S1). For endophytic bacteria, the Ace, Shannon, and Shannon evenness indices exhibited a consistent trend: HR > DRH > DRR. Notably, HR had significantly greater diversity than DRR (P ≤ 0.01), and DRH also had significantly higher Ace and Shannon indices than DRR (P ≤ 0.01) (Figs. 3A–3C, blue bars). For endophytic fungi, the Shannon evenness index was significantly higher in HR compared to DRR (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 3C, red bars). In the rhizosphere soil, bacterial Shannon and Shannon evenness indices were significantly greater in HS than in DS (P ≤ 0.01) (Figs. 3E–3F, blue bars). However, no significant differences in alpha diversity were detected between healthy and diseased samples in non-rhizosphere soil microbial communities (Figs. 3D–3F).

Figure 3: Microbial alpha diversity indices in L. chuanxiong.

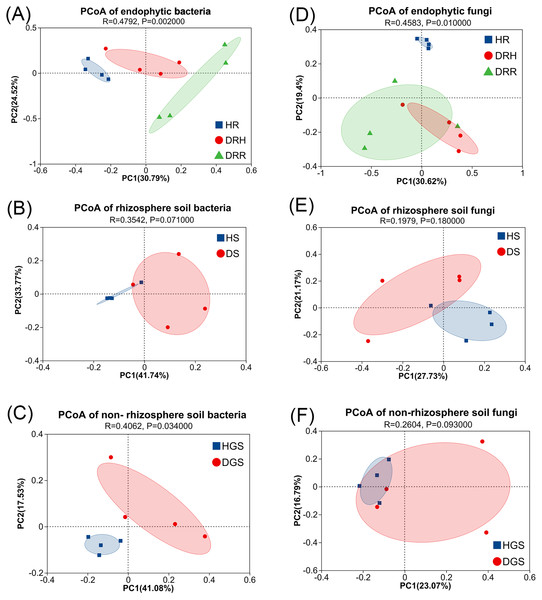

(A) ACE index of endophytic bacteria and fungi; (B) Shannon index of endophytic bacteria and fungi; (C) Shannon evenness index of endophytic bacteria and fungi; (D) ACE index of soil bacteria and fungi; (E) Shannon index of soil bacteria and fungi; (F) Shannon evenness index of soil bacteria and fungi.To evaluate microbial community structural shifts during L. chuanxiong root rot progression, we conducted Bray-Curtis distance-based principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) (Fig. 4) and hierarchical clustering (Fig. S4). The endophytic bacterial communities clearly differed among the HR, DRH, and DRR (Fig. 4A). Similarly, soil bacterial communities formed distinct clusters in HS vs. DS and HGS vs. DGS (Figs. 4B, 4C). Endophytic fungal communities partially overlapped between DRH and DRR, but HR distinctly clustered apart from both DRH and DRR (Fig. 4D). Rhizosphere soil fungi were clearly separated between HS and DS (Fig. 4E), whereas non-rhizosphere soil fungal communities (HGS and DGS) displayed overlapping distributions (Fig. 4F). Hierarchical clustering results were consistent with the PCoA, with healthy samples clustering more tightly than diseased samples (Fig. S4). Notably, the DRH bacterial community was more similar to that of HR (Fig. S4D), whereas the DRH fungal community clustered closer to DRR (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4: PCoA analysis of endophytic and soil microbial community structures during L. chuanxiong root rot progression.

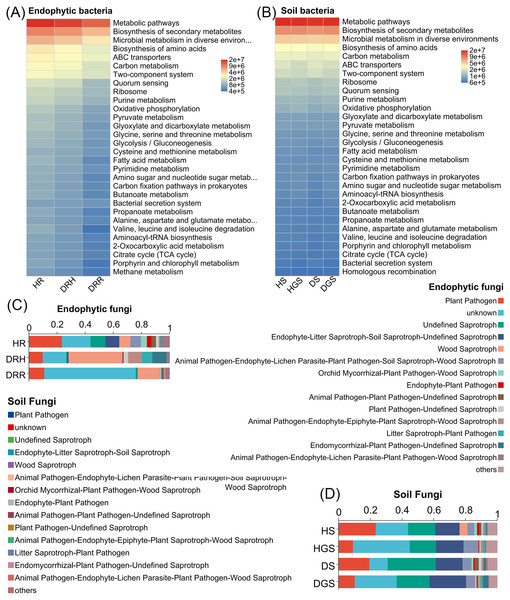

(A) Endophytic bacteria; (B) Rhizosphere soil bacteria; (C) Non-rhizosphere soil bacteria; (D) Endophytic fungi; (E) Rhizosphere soil fungi; (F) Non-rhizosphere soil fungi. The closer each sample point is, the more similar their microbial community composition.Additionally, microbial functional changes across different pathological stages of L. chuanxiong were predicted using PICRUSt2 and FUNGuild analyses (Fig. 5). The bacterial PICRUSt2 analysis (Figs. 5A, 5B) revealed a decline in metabolic, environmental adaptation, and genetic information processing activities of endophytic and soil bacteria in DRR, including pathways such as biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, ABC transporters, and aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis. The fungal FUNGuild classification (Figs. 5C, 5D) revealed fungal trophic transitions: HR was dominated by pathotroph-saprotroph-symbiotroph fungi, DRH exhibited increased pathotroph and pathotroph-saprotroph dominance, while decayed tissues and diseased soils (DRR/DS/DGS) became predominantly saprotrophic.

Figure 5: Functional prediction of endophytic and soil microbial communities in L. chuanxiong by PICRUSt 2 and FUNGuild.

(A) Endophytic bacteria; (B) Soil bacteria; (C) Endophytic fungi; (D) Soil fungi.In summary, the α-diversity was primarily observed in bacterial communities, with healthy rhizomes and rhizosphere soils harboring significantly richer and more diverse bacterial communities than diseased samples. Disease progression progressively reduced bacterial diversity indices, particularly in decayed tissues. The β-diversity analyses revealed distinct endophytic and rhizosphere soil microbial community structures (both bacterial and fungal) between healthy and decayed samples. Notably, at the transitional phase (DRH) from health to disease, bacterial communities remained more similar to those of healthy rhizomes, whereas fungal communities aligned closer to decayed tissues. Furthermore, disease progression was accompanied by a reduction in bacterial functional activity and a shift of fungal communities toward saprotrophic functions.

Composition and differential analysis of microbial species during L. chuanxiong root rot progression

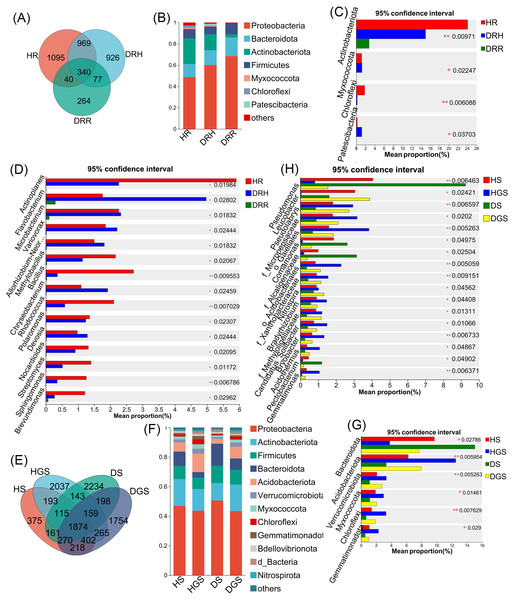

Bacterial species composition and differential analysis in L. chuanxiong

The Venn diagram revealed that endophytic bacteria represented 36.62%–44.80% differential OTUs across healthy, transitional, and decay stages (Fig. 6A), and soil bacterial communities showed 10.39%–43.34% differential OTUs between healthy and diseased samples (Fig. 6E). Further analysis focused on the relative abundance changes in the dominant bacterial taxa (relative abundance >1%) during the progression of disease in L. chuanxiong. At the phylum level, endophytic bacterial communities were mainly composed of seven dominant phyla (collectively accounting for >97.11% of total sequences), while soil bacterial communities comprised twelve dominant phyla (representing >98.00% of total sequences) (Figs. 6B, 6F). The relative abundance profiles of dominant bacterial genera are provided in (Figs. S5A, S5B). In healthy rhizomes (HR), the highest relative abundances were observed for Actinobacteriota, Chloroflexi, Bacillus, Sphingomonas, Rhodococcus, unclassified_f_Oxalobacteraceae, and norank_f_Ardenticatenaceae (all P ≤ 0.01), as well as Nocardioides, Brevundimonas, Streptomyces, and Polaromonas (all P ≤ 0.05). In contrast, disease transition phase (DRH) showed significantly higher abundances of Myxococcota, Microbacterium, Allorhizobium-Neorhizobium-Pararhizobium-Rhizobium, Variovorax, Flavobacterium, Chryseobacterium, Devosia (all P ≤ 0.05), and unclassified_p_Proteobacteria (P ≤ 0.01) (Figs. 6C, 6D). In soil samples, Chloroflexi, Gemmatimonas, norank_f_Xanthobacteraceae, Acidothermus, Pseudolabrys, norank_f_norank_o_Gaiellales, Bryobacter, and norank_f_norank_o_Elsterales (all P ≤ 0.01), along with Myxococcota, Bradyrhizobium, Candidatus_Solibacter, norank_f_Methyloligellaceae, norank_f_norank_o_Acidobacteriales, Nitrospira, norank_f_Micropepsaceae, and Haliangium (all P ≤ 0.05), were significantly enriched in healthy soils (HS, HGS). Conversely, Pseudomonas (P ≤ 0.01) and Omamonas, Ectobacterium, and unclassified_f_Alcaligenaceae (all P ≤ 0.05) presented relatively high abundances in diseased soils (DS, DGS) (Figs. 6G, 6H).

Figure 6: Composition and differential analysis of endophytic and soil bacterial communities in L. chuanxiong across distinct pathological stages.

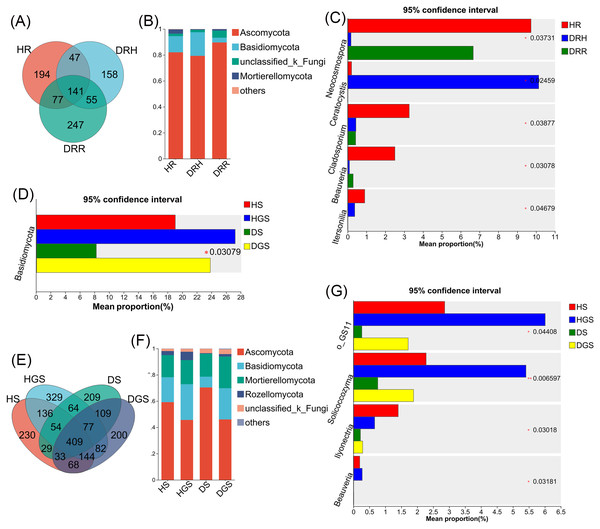

Venn diagrams of endophytic bacteria (A) and soil bacteria (E) at the OTU level, with numbers indicating the shared OTUs across different pathological stages; taxonomic composition of endophytic bacteria (B) and soil bacteria (F) at the phylum level; differential phyla of endophytic bacteria (C) and soil bacteria (G); differential genera of endophytic bacteria (D) and soil bacteria (H).Fungal species composition and differential analysis in L. chuanxiong

The Venn diagram revealed that differential OTUs of endophytic fungi accounted for 39.40% to 47.50% of the total OTUs across different pathological stages (Fig. 7A), and differential OTUs of soil fungi ranged from 17.83% to 25.41% (Fig. 7E). Further analysis focused on changes in the relative abundance of dominant fungi (relative abundance >1%) during disease progression. Across all samples, endophytic fungi were mainly composed of four dominant phyla (accounting for more than 99.74% of total sequences), while soil fungi primarily belonged to five dominant phyla (representing more than 99.48% of total sequences) (Figs. 7B, 7F). The relative abundance profiles of dominant fungal genera are provided in the supplementary materials (Figs. S5C, S5D). In HR, the genera Trichoderma, Beauveria, Neocosmospora, and Cladosporium exhibited the highest relative abundances (all P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 7C). In DRH, Ceratocystis (P ≤ 0.05) and Plectosphaerella showed the highest relative abundances (Fig. 7C; Fig. S5C). Among the soil samples, Solicoccozyma (P ≤ 0.01), Basidiomycota, Beauveria, Ilyonectria, and unclassified_o_GS11 (all P ≤ 0.05) were significantly enriched in healthy soils (HS, HGS) (Figs. 7D, 7G). Conversely, Gibberella, unclassified_f_Nectriaceae, and unclassified_f_Ceratobasidiaceae dominated in diseased soils, while their relative abundances were less than 1% in healthy soils (Fig. S5D).

Figure 7: Composition and differential analysis of endophytic and soil fungal communities in L. chuanxiong across distinct pathological stages.

Venn diagrams of endophytic fungi (A) and soil fungi (E) at the OTU level, with numbers indicating the shared OTUs across different pathological stages; taxonomic composition of endophytic fungi (B) and soil fungi (F) at the phylum level; differential phyla of endophytic fungi (C); differential genera of endophytic fungi (D) and soil fungi (G).Microbial co-occurrence network analysis in healthy and root rot L. chuanxiong

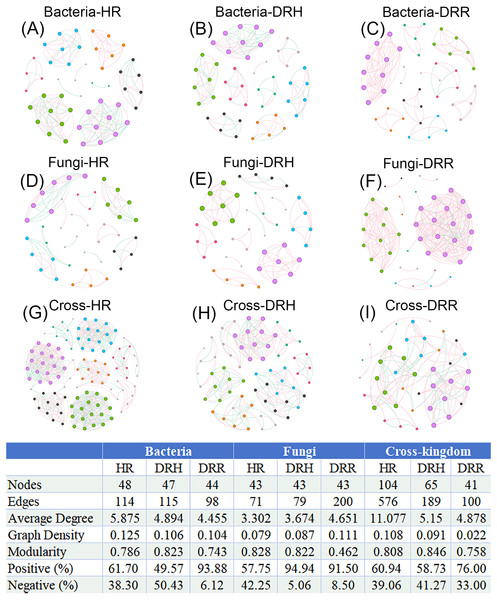

To illustrate the interaction characteristics and stability of L. chuanxiong microbial communities across different pathological stages, co-occurrence networks of bacteria, fungi, and cross-kingdom microbes were constructed based on Spearman correlations among dominant genera (P < 0.05). The number of edges (141), average degree (5.875), and network density (0.135) were higher in the endophytic bacterial co-occurrence network in healthy rhizomes (HR) than the edges (98), average degree (4.445), and network density (0.104) in rotten rhizomes (DRR) (Figs. 8A–8C). However, for the endophytic fungal network, the edges (200), average degree (4.651), and network density (0.111) were higher in rotten rhizomes (DRR) related to the edges (71), average degree (3.302), and network density (0.079) in healthy rhizomes (HR) (Figs. 8D–8F). Notably, the proportion of positive correlations in both bacterial and fungal networks was greater in DRR (bacteria: 93.88%; fungi: 91.50%) than in HR (bacteria: 61.70%; fungi: 57.75%) (Figs. 8A–8F). Furthermore, the cross-kingdom microbial co-occurrence networks showed a decreasing trend in positive correlations, nodes, edges, average degree, and network density in the order HR >DRH >DRR (Figs. 8G–8I).

Figure 8: Co-occurrence networks of endophytic bacteria, fungi and cross-kingdom microorganisms in L. chuanxiong under different pathological stages.

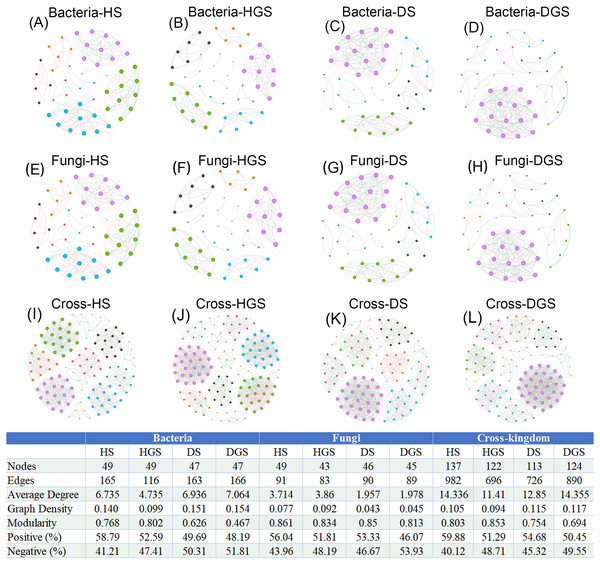

(A–C) represent endophytic bacterial networks of HR, DRH, and DRR, respectively; (D–F) represent endophytic fungal networks of HR, DRH, and DRR, respectively; (G–I) represent endophytic cross-kingdom networks of HR, DRH, and DRR, respectively. Different node colors indicate distinct modules. Red edges represent positive correlations, while blue edges indicate negative correlations. Abbreviations: HR, healthy rhizome; DRH, healthy layer of diseased rhizome; DRR, rot layer of diseased rhizome.In the co-occurrence networks of soil bacteria, the average degree (HS: 4.735, HGS: 6.735) and network density (HS: 0.099, HGS: 0.140) of healthy soils were lower than the average degree (DS: 6.936, DGS: 7.064) and network density (DS: 0.151, DGS: 0.154) of diseased soils (Figs. 9A–9D). In contrast, for soil fungal networks, the average degree (HS: 3.714, HGS: 3.860) and network density (HS: 0.077, HGS: 0.092) in healthy soils were higher than the average degree (DS: 1.957, DGS: 1.978) and network density (DS: 0.043, DGS: 0.045) in diseased soils (Figs. 9E–9H). Moreover, the cross-kingdom microbial co-occurrence network revealed that the nodes (137), edges (982), average degree (14.336), and modularity (0.803) in diseased rhizosphere soil (DGS) were lower than the nodes (113), edges (726), average degree (12.850), and modularity (0.754) in healthy rhizosphere soil (HS) (Figs. 9I–9L).

Figure 9: Co-occurrence networks of soil bacteria, fungi and cross-kingdom microorganisms in L. chuanxiong under different pathological stages.

(A, B) represent bacterial networks of healthy rhizosphere and non- rhizosphere soils; (C, D) bacterial networks of diseased rhizosphere and non- rhizosphere soils; (E, F) fungal networks of healthy rhizosphere and non- rhizosphere soils; (G, H) fungal networks of diseased rhizosphere and non- rhizosphere soils; (I, J) cross- kingdom networks of healthy rhizosphere and non- rhizosphere soils; (K, L) cross- kingdom networks of diseased rhizosphere and non- rhizosphere soils. Different node colors represent distinct modules. Red edges indicate positive correlations, while blue edges represent negative correlations. Abbreviations: HS, healthy rhizosphere soil; HGS, healthy non- rhizosphere soil; DS, diseased rhizosphere soil; DGS, diseased non- rhizosphere soil.In summary, endophytic bacteria and soil fungi presented increased network complexity and cohesion in healthy L. chuanxiong samples, whereas endophytic fungi and soil bacteria presented increased activity in decay-stage samples. Notably, the cross-kingdom interactions of endophytic and rhizosphere soil microbiomes were more stable in healthy plants, with greater microbial community activity and resilience than in diseased microbiomes. Under pathogen stress, endophytic microbiota shifted toward predominantly mutualistic relationships, while competitive and antagonistic interactions were significantly attenuated.

Discussion

The plant microbiome has long been recognized as an essential part of plant ecosystem and is closely associated with plant growth and disease resistance (Cordovez et al., 2019). Under pathogen stress, plants can use their root exudates to recruit beneficial microbes from the environment to increase their ability to combat the stress (Liu et al., 2020). These exudates often include organic acids, amino acids, phenolic compounds, and other secondary metabolites, which serve as nutrients or antimicrobial agents that facilitate the colonization of beneficial rhizosphere bacteria (Chen & Liu, 2022). Beyond root exudates, microbe-derived metabolites are also recognized as a promising source of functional compounds in the rhizosphere. Compounds such as carbohydrates, siderophores, exopolysaccharides, and malate, released by microbes, help establish a close association between the plant and its surrounding rhizosphere microbiome, mitigating various adverse conditions (Fan et al., 2025). This adaptive modification of the plant-associated microbiota, often described as a plant “cry for help” response, constitutes a positive ecological strategy to mitigate stress. For instance, Yin et al. (2021) reported that wheat plants continuously exposed to pathogenic fungi can reshape their rhizosphere microbial communities, particularly by recruiting beneficial microbes to suppress soil-borne fungal pathogens and promote plant growth. Similar plant-driven assembly of disease-suppressive microbiomes had also been observed in tomato crops, underscoring the broader relevance of this phenomenon across different plant species (Peng et al., 2025). Collectively, these dynamic shifts in microbial community composition hold potential for addressing agronomic challenges related to plant diseases.

This study investigated shifts in the microbial communities among healthy L. chuanxiong plants, the healthy layer of diseased plants, and the decayed layer. At the phylum level, we observed significant depletion of Chloroflexi and Myxococcota in diseased rhizomes and surrounding soil. These phyla include diverse predatory bacterial groups capable of consuming various bacteria and fungi, while possessing antimicrobial secondary metabolite biosynthesis potential, making them agriculturally valuable for biological control (Du et al., 2023; Xian, Zhang & Li, 2020). At the genus level, as disease severity increased, the relative abundances of potentially beneficial microbes, including Bacillus (0.03%), Trichoderma (0.89%), and Beauveria (0.29%), declined markedly, all falling below 1%. Notably, Bacillus and Trichoderma species are widely utilized as biocontrol agents against plant fungal pathogens (Zanon et al., 2024; Harman, 2008), while the entomopathogen Beauveria promotes plant growth and suppresses Fusarium-induced crown rot in wheat (Jaber, 2018). Conversely, the abundance of pathogenic and potentially pathogenic genera, including Gibberella and Pectobacterium, significantly increased. Gibberella represents the sexual reproductive stage of certain Fusarium species, that were originally identified in rice bakanae disease (Crous et al., 2022). Many members of these genera are recognized plant pathogens (Zhang et al., 2023), including F. oxysporum, F. solani, and F. asiaticum, which have been implicated in L. chuanxiong root rot (Li et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2022). Pectobacterium, a broad-host-range bacterial pathogen, primarily causes soft rot diseases through critical virulence factors like cell wall-degrading enzymes (Li et al., 2019). Importantly, our findings corroborate previous studies identifying Bacillus and Trichoderma as key differential taxa between healthy and diseased L. chuanxiong rhizosphere microbiomes (Sun et al., 2024), highlighting their promising potential for developing biocontrol strategies against root rot.

Notably, the “transition phase” (the healthy layer of diseased rhizomes) exhibited dual-phase microbial community shifts during root rot progression. This ecotone harbored an increased abundance of potentially pathogenic fungi, including Ceratocystis, the primary causal agent of sweet potato black rot (Wang, Tian & Liu, 2023; Wang, TIian & Liu, 2023), and Plectosphaerella, which is associated with stunting disease in tomato and pepper crops (Raimondo & Carlucci, 2017). In contrast to the fungal community shifts, the bacterial community structure at this transition phase more closely resembled that of healthy rhizomes, showing selective enrichment of potentially beneficial taxa: Microbacterium, Variovorax, Allorhizobium-Neorhizobium-Pararhizobium-Rhizobium, Flavobacterium, and Chryseobacterium. In addition, Microbacterium demonstrates remarkable environmental adaptability across wide temperature, salinity, and pH ranges, aiding plant stress tolerance (Zhao et al., 2024); Variovorax modulates phytohormone homeostasis to maintain root architecture development (Finkel et al., 2020); while Rhizobium spp. exhibit high nitrogenase activity and serve as effective biofertilizers (Shameem et al., 2022). Additionally, Flavobacterium and Chryseobacterium have demonstrated antagonistic activity against sugar beet wilt and rice blast diseases, respectively (Carrión et al., 2019; Kumar et al., 2021). Overall, the enrichment of beneficial bacteria in the healthy layer of diseased L. chuanxiong rhizomes suggests that, during the early pathogen invasion, the plant may actively restructure its microbiome to recruit and accumulate advantageous bacteria, thereby enhancing resistance and delaying disease progression. These findings are consistent with those of Carrión et al. (2019) who showed that pathogen-induced endophytic bacteria suppress fungal diseases through activation of specific biosynthetic gene clusters, as confirmed by transcriptomic analyses. Therefore, future studies on synthetic microbial consortia for combating L. chuanxiong root rot should incorporate these beneficial bacterial taxa to validate their role in enhancing host resistance. Such efforts will not only advance our understanding of plant-microbe interactions but also provide a theoretical foundation for developing novel biocontrol strategies leveraging beneficial bacteria.

Microbial community structure and function are dynamically regulated by interaction networks, where increased network complexity typically correlates with enhanced metabolic activity and ecosystem resilience (Gao et al., 2021; Wagg et al., 2019). In this study, root rot infection in L. chuanxiong substantially destabilized rhizosphere microbial networks across kingdoms, coinciding with reduced bacterial functional activity and fungal community transition toward saprotrophic dominance. These findings highlight microbiome stability as a critical determinant of plant health. Concurrently, microbial networks in diseased rhizomes showed increased positive correlations, reflecting pathogen enrichment alongside opportunistic colonizers of necrotic tissue. While this pattern implies strengthened cooperative interactions among surviving microbiota (Herren & McMahon, 2017), established ecological theory posits that competitive networks typically promote community stability and stress resistance (Coyte, Schluter & Foster, 2015). The observed reduction in competitive interactions within the diseased L. chuanxiong microbiome likely explains both the network instability and functional dysbiosis, potentially creating favorable conditions for pathogen expansion. It should be noted that functional predictions derived from genus-level taxonomy (via PICRUSt2/FUNGuild) represent hypothetical capacities rather than demonstrated activities. Experimental validation remains essential to confirm these metabolic inferences. Nevertheless, our findings reinforce that maintaining plant health relies on the assembly of a diverse and intricate microbial community, rather than the simple introduction of one or a few microbial taxa (Wang et al., 2024b). In summary, this study elucidates the shifts in endophytic and soil microbial communities during the onset and progression of L. chuanxiong root rot, highlighting the disease-suppressive potential of endophytic bacterial assemblages in the early stages of infection. Future research should focus on designing targeted synthetic consortia of beneficial bacteria based on pathogen-induced microbial shifts, followed by validation of their disease-suppressive effects through pot experiments and long-term field trials.

Conclusion

This study elucidates the response characteristics of microbial communities during the progression of Ligusticum chuanxiong root rot, providing a theoretical foundation for developing microecological control strategies against this disease. Under pathological conditions, the imbalance of endophytic and soil microecosystems in L. chuanxiong is accompanied by decreased bacterial diversity and functional activity, along with weakened stability of cross-kingdom bacterial-fungal interaction networks and reduced competitive constraints. Comparative analysis revealed significant depletion of potentially beneficial microbial taxa in diseased plants (e.g., endophytic Bacillus and Trichoderma, soil-dwelling Candidatus_Solibacter and Beauveria) alongside enrichment of potential pathogens (e.g., soil-borne Pectobacterium and Gibberella). Notably, rhizome-rotted L. chuanxiong did not completely lose beneficial microbiota. During the health-to-disease transition phase, endophytic communities exhibit dualistic dynamics: bacterial communities demonstrate disease-suppressive potential with increased beneficial taxa (e.g., Microbacterium and Variovorax), while fungal communities shift toward pathogenicity with enriched deleterious species (e.g., Ceratocystis and Plectosphaerella). These findings suggest that endophytic bacteria may play more protective roles than fungi in terms of root rot resistance. Crucially, the holistic assembly of microbial communities rather than individual species mainten L. chuanxiong health.

Supplemental Information

Microbial alpha diversity indices in healthy and root rot-infected L. chuanxiong

Different lowercase letters within the same sample type indicate statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05). Abbreviations: HR, healthy rhizome; DRH, healthy layer of diseased rhizome; DRR, rot layer of diseased rhizome ; HS, healthy rhizosphere soil; HGS, healthy non- rhizosphere soil; DS, diseased rhizosphere soil; DGS, diseased non- rhizosphere soil.

Validation of surface sterilization efficacy for L. chuanxiong rhizome tissues

The LB agar plate was spread with the final rinse water obtained after the three washes during the surface sterilization of L. chuanxiong tissues, verifying the aseptic condition of the sample surfaces.

Morphological characteristics of pathogen isolates (Fusarium solani andF. oxysporum).

(a) Front and reverse colony morphology of F. oxysporum; (b) Macroconidia of F. oxysporum; (c, d) Microconidia of F. oxysporum; (e) Chlamydospores of F. oxysporum; (f) Sporulating cells of F. oxysporum. (g) Front and reverse colony morphology of F. solani; (h) Macroconidia of F. solani; (i, j) Microconidia of F. solani; (k) Chlamydospores of F. solani; (l) Hyphae of F. solani.

Rarefaction curves of bacterial (a) and fungal (b) sequencing in L. chuanxiong

Hierarchical clustering analysis of endophytic and soil microbial community structures of L. chuanxiong at different pathological stages.

(a) Endophytic bacteria; (b) Rhizosphere soil bacteria; (c) Non-rhizosphere soil bacteria; (d) Endophytic fungi; (e) Rhizosphere soil fungi; (f) Non-rhizosphere soil fungi.

Taxonomic composition and relative abundance of endophytic and soil microbial communities in L. chuanxiong at the genus level

Composition of dominant bacterial genera in endophytes (a) and soil bacteria (b); composition of dominant fungal genera in endophytes (c) and soil fungi (d).