Bioinformatics-based identification of RAS disequilibrium involved in post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph return-mediated acute kidney injury in mice

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Vladimir Uversky

- Subject Areas

- Biochemistry, Nephrology, Urology, Histology

- Keywords

- Hemorrhagic shock, Acute kidney injury, Renin-angiotensin system, Angiotensin converting enzyme, Mesenteric lymph

- Copyright

- © 2025 Jin et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Bioinformatics-based identification of RAS disequilibrium involved in post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph return-mediated acute kidney injury in mice. PeerJ 13:e20359 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20359

Abstract

Post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph (PHSML) return plays a critical role in the development of acute kidney injury (AKI). However, the molecular mechanism underlying PHSML-mediated AKI remains unclear. In this study, bioinformatics analysis identified key common targets of hemorrhagic shock and AKI, revealing significant enrichment in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). To further investigate the role of RAS in PHSML-mediated AKI, we established mesenteric lymph duct ligation (MLDL) technology in mice and confirmed that MLDL alleviated hemorrhagic shock-induced AKI. Subsequently, male C57BL/6 mice subjected to hemorrhagic shock were treated with the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril, angiotensin (1-7) (Ang (1-7)), and angiotensin II (Ang II) type 1 receptor (AT1R) inhibitor losartan. Additionally, mice with hemorrhage and MLDL were treated with Ang II, the Mas receptor (MasR) inhibitor A-779, or subjected to Ace2 knockout. Renal histomorphology, expression of ACE, ACE2, AT1R, and MasR, and levels of Ang II and Ang (1-7) were assessed 4 h after resuscitation. The results demonstrated that hemorrhagic shock upregulated ACE and AT1R, while downregulating ACE2 and MasR, accompanied by elevated Ang II and reduced Ang (1-7). These adverse effects were partially reversed by MLDL, enalapril, Ang-(1-7), or losartan. Conversely, the beneficial role of MLDL was abolished by Ace2 deficiency and the administration of Ang II and A-779. Collectively, these findings indicate that disequilibrium between the ACE-AngII-AT1R and ACE2-Ang (1-7)-MasR axes is implicated in PHSML-mediated AKI.

Introduction

Hemorrhagic shock, triggered by various pathogenic factors, such as trauma, peptic ulcers, and intraoperative hemorrhage, is a critical clinical condition associated with high morbidity and mortality (Cannon, 2018). Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication following hemorrhagic shock and ischemia/reperfusion (Gröger et al., 2022; Xue et al., 2021), exacerbating systemic disturbances and significantly increasing mortality rates (Gröger et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2020). Therefore, attention should be paid to changes in renal function during severe hemorrhagic shock. Data from rat models indicate that post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph (PHSML) return is involved in hemorrhagic shock-induced AKI, and blockage of PHSML return alleviates AKI by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress (Han et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016; Niu et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2014). To further investigate the potential mechanism of PHSML-induced AKI, bioinformatic analysis identified key common targets of hemorrhagic shock and AKI, revealing significant enrichment in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). RAS contains two main axes: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-angiotensin (Ang) II-Ang II 1 receptor (AT1R) and ACE2-Ang (1-7)-Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor (MasR) (Zhang et al., 2018). Activation of ACE-Ang II-AT1R increases Ang II synthesis and leads to vasoconstriction, reabsorption of water and sodium, hypertension, inflammation, and fibrosis in renal tissue, resulting in AKI (Fisler et al., 2024). Ang II leads to kidney injury through AT1R and AT2R activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling and pro-inflammatory genes, promoting monocyte aggregation and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (Alique et al., 2015). Moreover, upregulated ACE2 expression improves the ACE/ACE2 imbalance and alleviates AKI (Shirazi et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2012). In addition, the imbalance of ACE/ACE2 is involved in AKI caused by tourniquet-induced ischemia-reperfusion in the hind limbs, which also appears in Ace2-/- mice along with the upregulated expression of ACE/Ang II (Yang et al., 2012). However, it remains unclear whether ACE/ACE2 imbalance is involved in the occurrence of PHSML return-induced AKI. Recent studies have highlighted the potential interaction between the ACE/ACE2/AT1R axis and vascular regulation pathways as well as their involvement in inflammation during shock-induced organ injury. Therefore, we investigated the role of the ACE/ACE2 imbalance in PHSML-mediated kidney injury using drugs related to the ACE/ACE2 axis and gene knockout mice.

Materials & Methods

Materials

Ang II (10271406) and Ang (1-7) (32GGAM12G1) were purchased from Enzo (Farmingdale, NY, USA). Enalapril (CDS020548) and Losartan Potassium (LRAA4718) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). A779 (P14701408) was purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Anti-ACE (ab11734), Anti-ACE2 antibody (ab108252), and Anti-AT1R antibody (ab124505) antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Anti-Mas1R antibody (AV51197) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Immunohistochemical kits were obtained from Boster (Wuhan, China). The BCA kit was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). ELISA kits for Ang II and Ang (1-7) were purchased from Huiying Biological Technology (Shanghai, China).

Methods

Screening of targets related to hemorrhagic shock and acute kidney injury

We utilized “Hemorrhagic shock” and “Acute kidney Injury” as search terms respectively, conducting searches in databases including GeneCards, OMIM, and TTD.1 In the GeneCards database, the screening criteria were set as a score of ≥10. After summarizing the screening results and eliminating duplicates, we separately obtained gene sets related to hemorrhagic shock and acute kidney injury. By taking the intersection of these two gene sets, we identified the genes associated with both hemorrhagic shock and acute kidney injury.

Construction of protein-protein interaction network

The intersection gene set obtained in the previous step was input into the STRING database, with the protein species set to “Homo sapiens” and the minimum interaction threshold set to 0.4. The PPI network data of the intersecting genes were retrieved and imported into Cytoscape for visualization. The MCODE plugin in Cytoscape was used to analyze the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and identify tightly connected sub-networks.

Enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed on the intersection gene set using the Bioconductor bioinformatics package in R software (P-value <0.05, Q-value <0.05). The results were presented in a bubble plot format.

ACE expression validation

To validate the expression of ACE in AKI, we analyzed the GSE225349 dataset obtained from the GEO database. This dataset includes proteomic data from plasma samples of COVID-19 inpatients, with the AKI group consisting of those with stage 2 or 3 COVID-induced AKI, and the control group including patients with stage 1 AKI or those without AKI. The raw expression data for ACE were extracted from the dataset and compared between the AKI and control groups using the R software. After preprocessing the data, box plots were generated using the SangerBox platform to visualize the differential expression of ACE in the two cohorts.

Animal and experimental group

Healthy male wild-type C57 mice (25 ± 2 g) were obtained from the Academy of Military Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). Ace2-/- mice were obtained from the North China University of Science and Technology. After adaptive feeding, all mice were randomly divided into nine groups (n = 6). First, Sham, Shock, Shock+ligation mice were used to observe the effect of mesenteric lymph duct ligation (MLDL) on hemorrhagic shock. Second, Shock+Enalapril, Shock+Losartan, Shock+Ang (1-7) were used to confirm the inhibitory effects of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis on hemorrhagic shock. Third, Shock+ligation+Ace2-/-, Shock+ligation+Ang II, and Shock+ligation+A-779 were used to verify the effects of ACE2/Ang (1-7)/MasR axis inhibition on MLDL. The mice were fasted for 12 h and allowed to drink freely before the experiment. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Hebei North University (approval number: 2015-1-0-03).

Hemorrhagic shock model

Mice were subjected to hemorrhagic shock as previously described (Yue et al., 2021), maintaining a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 40 ± 2 mmHg for 60 min, followed by resuscitation with shed whole blood and an equal volume of Ringer’s solution. The same procedure was performed without hemorrhage or resuscitation in the sham group. MLDL was measured as soon as the end of resuscitation in the shock +ligation, shock + ligation+Ace2-/-, Shock+ligation+Ang II, and Shock+ligation+A-779 groups. The ACE inhibitor Enalapril, Ang II antagonistic substance Ang (1-7), and AT1R inhibitor Losartan Potassium were administered at doses of 10 mg/kg (Seifi et al., 2024), 1 × 10−7 mol/kg (Jadli et al., 2023), and 50 mg/kg and resuscitation was performed in the Shock+Enalapril, Shock+Ang (1-7), and Shock+Losartan groups, respectively. In addition, parts of mice with hemorrhage plus MLDL were treated with Ang (1-7) antagonistic substance Ang II (1 × 10−7 mol/kg), MasR inhibitor A-779 (0.1 mg/kg), and resuscitation, respectively. Murine kidneys were collected 4 h after resuscitation or at corresponding time points for further research. The left kidney of each mouse was used for histopathological observation and immunohistochemistry and the right kidney was used for ELISA.

Histopathology observation

Left renal tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, paraffin-embedded samples were cut into 4 µm sections, conventionally deparaffinized, and stained with H&E. The tissues were observed under an optical microscope.

Immunohistochemistry assay

After the samples were cut into 4 µm sections, they were incubated with the primary antibody (ACE, 1:50; ACE2, 1:200; AT1R, 1:400; MasR, 1:200) at 4 °C overnight. Sections were subsequently incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies. Nuclei were stained with hematoxylin. The sections were observed under an optical microscope.

ELISA assay

Renal Ang II and Ang (1-7) levels were measured using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Proteins were detected using a BCA kit for standardization. The optical density of each well was measured at 450 nm using a multiscan spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M3; Molecular Devices).

Data presentation and statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± SD or mean ± SE and analyzed with SPSS 22.0 software. Differences among different groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the SNK test. The Tamhame2 T2 test was used for comparisons among different groups with heterogeneity of variance. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

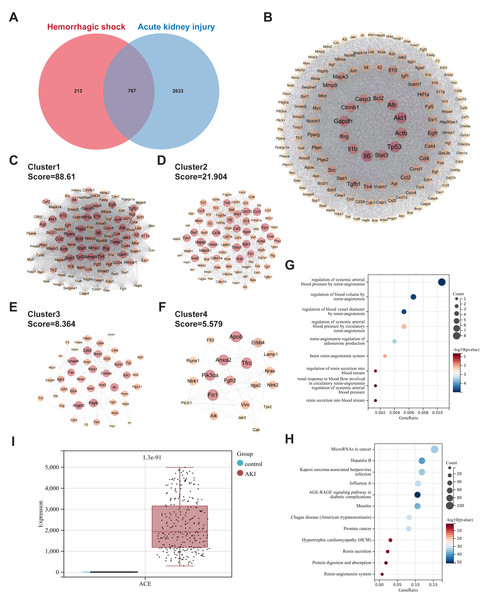

Identification of common targets and pathway analysis in hemorrhagic shock and acute kidney injury

Using “Hemorrhagic shock” as the search term, 980 targets were identified after deduplication across the three databases (GeneCards, OMIM, TTD). For “Acute Kidney Injury”, 3400 targets were retrieved, resulting in 767 overlapping genes (Fig. 1A). The protein-protein interaction network contained 690 nodes and 24503 edges (Fig. 1B). MCODE clustering analysis revealed four sub-networks with the following network scores: MCODE Cluster 1 Score = 88.61, MCODE Cluster 2 Score = 21.90, MCODE Cluster 3 Score = 8.36, and MCODE Cluster 4 Score = 5.57 (Figs. 1C–1F). GO enrichment analysis revealed that the intersection gene set was enriched in the regulation of systemic arterial blood pressure by the renin-angiotensin system, regulation of blood volume by the renin-angiotensin system, and regulation of blood vessel diameter by the renin-angiotensin system (Fig. 1G). KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that the intersection gene set was significantly enriched in pathways, such as microRNAs in cancer, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection, and the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications (Fig. 1H). Analysis of the GSE225349 dataset revealed significant upregulation of ACE expression in the AKI group compared to that in the control group (Fig. 1I).

Figure 1: Common targets and functional analyses of hemorrhagic shock and acute kidney injury.

(A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of genes related to hemorrhagic shock and acute kidney injury. (B) PPI network of the intersecting genes. (C–F) Sub-networks identified by MCODE clustering analysis of the PPI network. (G) GO enrichment analysis of biological processes associated with common gene sets. (H) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the common gene set. (I) Validation of ACE expression in the GSE225349 dataset.Mesenteric lymph duct ligation alleviated renal tissue injury in mice after hemorrhagic shock

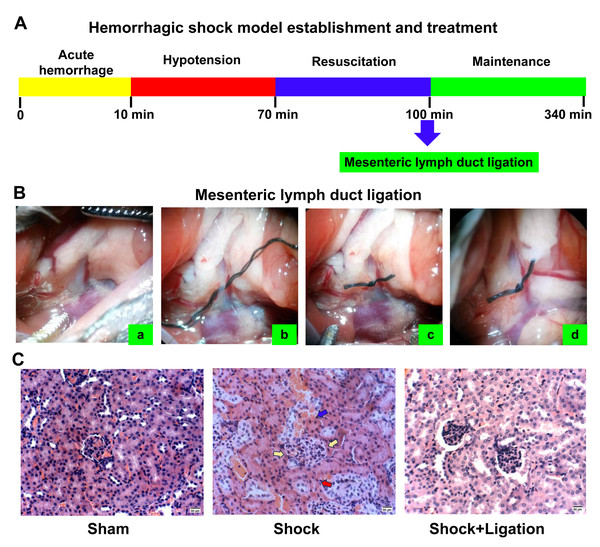

Figure 2C shows that hemorrhagic shock induces pathological injury in the kidneys. Compared to the sham group, mesangial cells were proliferating, the basement membrane was ruptured, glomeruli were compressed, renal tubular epithelial cells showed high edema, and even extended into the vessel cavity. Renal tubules exhibited luminal dilation with epithelial flattening due to severe edema, accompanied by intraluminal protein casts. Compared with the shock group, the kidneys in the shock+ligation group showed less severe pathological changes. Mesangial cells proliferated, but glomeruli without compression, renal tubular epithelial cells showed edema, renal tubules were slightly narrowed, and exfoliative protein of the renal tubular epithelium was observed.

Figure 2: Experimental procedure and renal morphological observations.

(A) Procedure for establishing the hemorrhagic shock model. (B) Mesenteric lymph duct (MLD) ligation. Location of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and MLD (A); threading under MLD (B); MLD ligation (C); MLD four hours after MLD ligation (D). (C) Representative images of renal tissue obtained from mice following hemorrhagic shock (bar = 50 µm). Yellow arrows indicate glomerular compression, red arrows denote basement membrane rupture, and blue arrows highlight epithelial–vascular extension.MLDL restored the balance of ACE and ACE2 axis in the kidney of mice after hemorrhagic shock

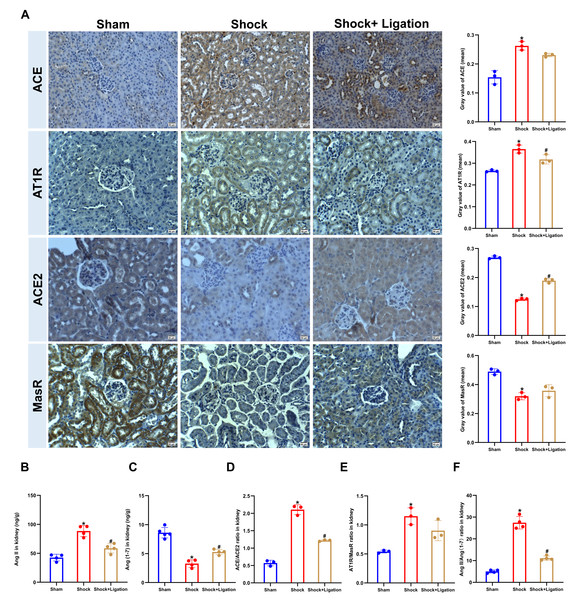

Compared to the sham group, ACE and AT1R protein expression and Ang II levels in the kidneys of mice were significantly increased in the shock group (Figs. 3A–3B), along with decreased ACE2, MasR, and Ang (1-7) (Figs. 3A, 3C). Meanwhile, MLDL decreased ACE and AT1R expression and Ang II levels in the kidneys of mice following hemorrhagic shock, and increased ACE2 and MasR expression and Ang (1-7) level. Moreover, MLDL restored the ratios of ACE/ACE2 and Ang II/Ang (1-7) (Figs. 3D–3F).

Figure 3: Effect of MLDL on ACE, ACE2, and related signaling molecules in renal tissue of mice following hemorrhagic shock.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical staining images (ACE, ATIR, ACE2, MasR, bar = 50 µm) and corresponding quantification (mean grayscale values). (B) Renal Ang II levels (ELISA). (C) Renal Ang (1-7) levels (ELISA). (D–F) Ratios of ACE-ACE2, ATIR/MasR and Ang II/Ang (1-7). Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3–5). *P < 0.05, compared with the sham group; #P < 0.05, compared with the shock group.Inhibition of ACE/Ang II/ AT1R axis alleviated renal tissue injury and decreased ACE and AT1R expressions in mice after hemorrhagic shock

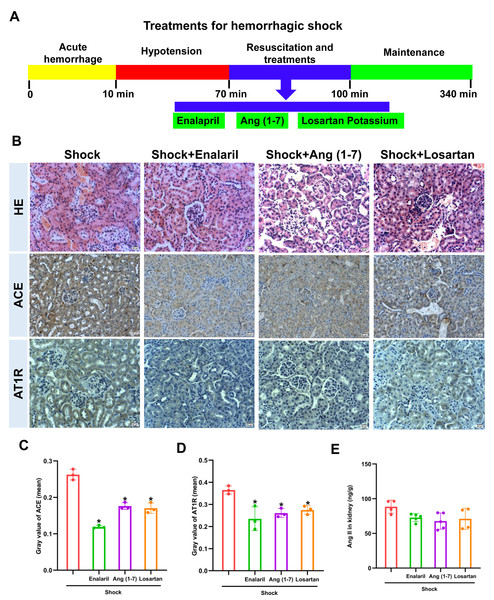

The treatments of enalapril, Ang (1-7), and losartan were performed as Fig. 4A, and alleviated the renal tissue injury in mice following hemorrhagic shock, which were characterized by slight proliferation of mesangial cells and mild edema of renal tubular epithelial cells (Fig. 4B). In addition, treatment with enalapril, Ang (1-7), and losartan decreased ACE and AT1R protein expression, but had no obvious effect on Ang II levels in the kidneys of mice following hemorrhagic shock (Figs. 4C, 4D, 4E).

Figure 4: Effect of enalapril, Ang (1-7), and losartan on renal injury and ACE/AT1R expression in the renal tissue of mice following hemorrhagic shock.

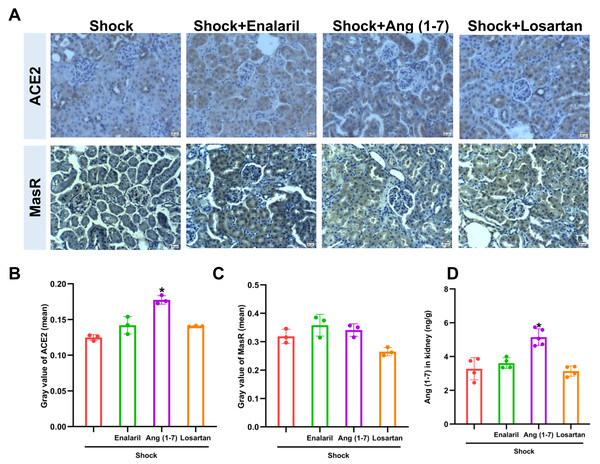

(A) Treatment timeline for enalapril, Ang (1-7), and losartan. (B) Representative HE-stained and immunohistochemically stained renal sections (bar = 50 µm). (C) Quantification of ACE expression in renal tissue (mean grayscale values). (D) Quantification of AT1R expression in renal tissue (mean grayscale values). (E) Ang II levels in renal tissue. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3–5). *P < 0.05, compared with the Shock group.Inhibition of ACE/Ang II/ AT1R axis partially regulated the ACE2 axis in mice after hemorrhagic shock

Ang (1-7) administration enhanced ACE2 expression and Ang (1-7) level in mice that underwent hemorrhagic shock, but had no effect on MasR expression (Fig. 5). In addition, treatment with enalapril and losartan did not affect ACE2, AT1R, or Ang (1-7) in mice subjected to hemorrhagic shock.

Figure 5: Effects of ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis inhibition on ACE2 expression and Ang (1-7) levels in mice following hemorrhagic shock.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical staining images for ACE2 and MasR (bar = 50 µm). (B) Quantification of ACE2 expression in renal tissue (mean grayscale values). (C) Quantification of MasR expression in renal tissue (mean grayscale values). (D) Ang (1-7) levels in renal tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3–5). *P < 0.05, compared with the Shock group.Inhibition of ACE2/Ang (1-7)/MasR axis partially abolished the MLDL beneficial effects on mice after hemorrhagic shock

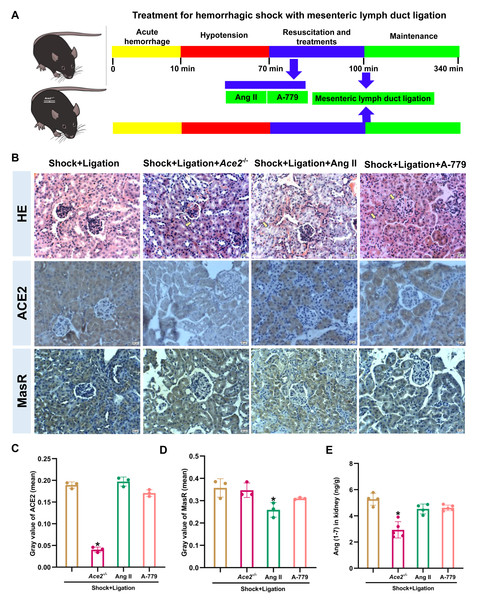

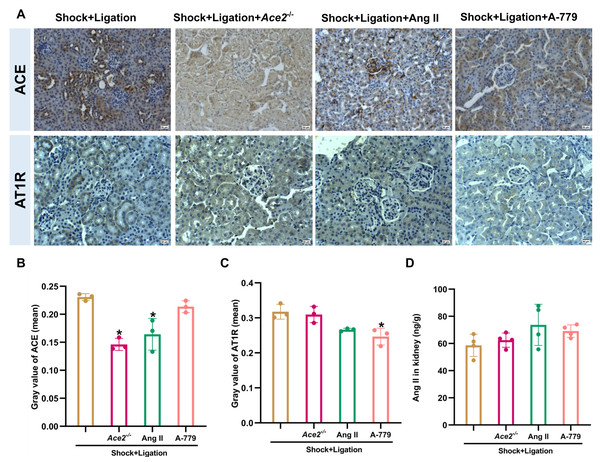

The Ace2 knockout and Ang II and A-779 administrations were executed as shown in Fig. 6A, and induced more severe pathological injury in the kidneys of mice following hemorrhagic shock plus MLDL (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, Ace2 knockout reduced ACE2, Ang (1-7), and ACE expression or levels; Ang II administration decreased MasR and ACE expression; and A-779 treatment reduced AT1R expression in the kidneys of mice following hemorrhagic shock plus MLDL (Fig. 7).

Figure 6: Disruption of the ACE2/Ang (1-7)/MasR axis exacerbates kidney injury and alters key molecular expression in rats after hemorrhagic shock treated with MLDL.

(A) Experimental timeline for Ace2 knockout, Ang II, and A-779 treatment in combination with MLDL. (B) Representative HE-stained and immunohistochemically stained renal sections (bar = 50 µm). Arrows indicate representative areas of tubular necrosis, glomerular atrophy/necrosis, and tubular swelling. (C) Quantification of ACE2 expression in renal tissue (mean grayscale values). (D) Quantification of MasR expression in renal tissue (mean grayscale values). (E) Ang (1-7) levels in the kidney. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3–5). *P < 0.05, compared with the shock + ligation group.Figure 7: Changes in ACE, AT1R, and Ang II levels in the renal tissue of mice following hemorrhagic shock.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical staining images of ACE and AT1R expression (bar = 50 µm). (B–C) Quantification of ACE and AT1R expression (mean grayscale values). (D) Ang II levels in renal tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3–4). *P < 0.05, compared with the shock + ligation group.Discussion

In this study, we identified a set of common genes related to both hemorrhagic shock and AKI, followed by a functional analysis to explore their potential roles in AKI. Our PPI network and enrichment analysis revealed that these genes are significantly involved in processes such as the regulation of systemic arterial blood pressure, blood volume, and blood vessel diameter, all of which are tightly regulated by the renin-angiotensin system. These biological processes are highly relevant to the pathophysiology of AKI, and endothelial dysfunction and impaired vascular regulation often contribute to kidney injury and dysfunction.

Notably, our analysis suggests that genes related to the ACE/ACE2 axis are among the potential key players in this network. ACE, a critical component of the renin-angiotensin system, is known to promote vasoconstriction and inflammation, and exacerbate AKI (Yi et al., 2023). In contrast, ACE2, through the conversion of Ang II to Ang (1-7), plays a protective role by mitigating these harmful effects (Xu, Chen & Yu, 2022). The enrichment of pathways such as the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications further supports the involvement of ACE/ACE2 in modulating renal injury. ACE2’s protective effects are believed to counteract the damaging effects of ACE and may be particularly relevant in conditions such as AKI, where both inflammatory and oxidative stress responses are heightened.

Furthermore, the subnetworks identified in the PPI analysis highlighted tightly connected clusters of genes that may serve as additional targets for modulating the ACE/ACE2 pathway. These sub-networks could potentially represent new molecular mechanisms by which ACE and ACE2 influence the pathogenesis of AKI, further emphasizing their crucial roles in kidney homeostasis and the injury response.

The current study investigated the role of ACE/ACE2 in PHSML-mediated AKI based on previous studies. Hemorrhagic shock induced RAS imbalance in mice, which was characterized by ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis upregulation and ACE2-Ang (1-7)-MasR axis downregulation. ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis inhibition and MLDL reduced kidney injury through the reestablishment of the RAS balance. Conversely, inhibition of ACE2-Ang (1-7)-MasR abolished the beneficial effects of MLDL in alleviating kidney injury. These results suggest that an imbalance in RAS is involved in kidney injury mediated by PHSML.

As the mice were euthanized at 4 h post-resuscitation, we did not assess blood urea nitrogen (BUN) or serum creatinine levels, since these serologic markers may not yet be elevated at such an early time point. Instead, we focused on histopathological changes, which have been reported to occur prior to detectable changes in serum markers during the early stages of AKI. Therefore, histological assessment served as the main criterion for evaluating kidney injury in this study. One limitation of this study is that histological scoring was based on three fields per sample due to constraints in tissue sectioning and image capture. Although efforts were made to minimize bias through blinded and standardized selection, we recognize the need for more extensive sampling and will address this in future research.

Histological observations showed that hemorrhagic shock induces severe renal injury, which is consistent with the results of a previous study (Choi et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2024). The injury was significantly alleviated after treatment with Enalapril, Ang (1-7), and losartan. MLDL alleviated kidney injury in mice following hemorrhagic shock. Intervention with Ang II, A-779, and Ace2 knockout abolished the beneficial effects of MLDL. The results preliminarily showed a relationship between hemorrhagic shock-induced kidney injury and ACE/ACE2 imbalance in mice, with similar changes in hindlimb ischemia-reperfusion-induced AKI (Yang et al., 2012) and sepsis-associated AKI (Garcia et al., 2023).

ACE is an important component of RAS, which is expressed in the glomeruli and tubules. The expression of ACE in the kidney increases significantly and participates in the process of kidney injury in sepsis (Rice et al., 1983). Our study showed that hemorrhagic shock significantly increased ACE and AT1R protein expression and Ang II levels in the kidneys, which was reversed by the administration of Enalapril, Losartan and Ang (1-7), respectively. These results indicate that changing the balance of ACE/ACE2 in mice could not only change the expression of ACE in the kidney but also alleviate kidney injury by regulating the expression of downstream receptors; however, the detailed mechanism remains to be further investigated. Excessive Ang II leads to water-sodium retention, increased intraglomerular pressure, mesangial cells, and mesangial matrix increase, causing the downregulation of renal function. This mechanism is related to the activation of AMPK/mTOR, TLR4/NF-κB, and TGF-β signaling (Fujihara et al., 2017; Mehta et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2016).

ACE2 is a newly discovered carboxypeptidase in recent years, which converts Ang II into protective Ang (1-7), which acts on MasR to effect. Our data demonstrated that hemorrhagic shock significantly decreased ACE2 protein expression in the kidney, which was significantly increased by the administration of Enalapril, Losartan, and Ang (1-7), accompanied by increased MasR expression and Ang (1-7) level. Previous studies have shown that enalapril upregulates ACE2 expression and downregulates ACE expression in the hearts of spontaneously hypertensive rats (Yang et al., 2013). Klimas et al. reported that losartan upregulated ACE2 and MasR expression in the kidneys of spontaneously hypertensive rats (Klimas et al., 2015). These findings suggest that the above drugs can upregulate ACE2 and MasR expression in the kidney, while downregulating ACE expression. A possible mechanism is inhibition of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-κB signaling (Li et al., 2015a; Li et al., 2015b). However, the specific mechanism requires further investigation.

Previous experiments have confirmed that PHSML is an important factor in organ injury, and blocking PHSML return can reduce organ injury (Liu et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). In this study, mesenteric lymphatic ligation abolished hemorrhagic shock-induced increases in ACE and AT1R expression and Ang II levels, and increased the expression of ACE2, MasR, and Ang (1-7), which revealed the favorable role of PHSML blockage. After the administration of Ang II and the MasR blocker A-779, the pathological changes in the kidney in the mesenteric lymphatic ligation group were significantly more severe than those in the shock group, accompanied by a decrease in ACE2 and MasR and an increase in ACE and AT1R. In addition, Ace2-/- mice showed more severe histopathological changes than MLDL-treated mice after hemorrhagic shock. This exacerbated renal injury was associated with disrupted ACE/ACE2 balance (see elevated ACE and Ang II in Fig. 7), thereby suppressing MasR activation. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the absence of shock-only and shock+MLDL groups within Fig. 6 restricts direct visual comparison in that figure, although these conditions were shown in earlier figures. To address this, arrows have been added in the revised images to highlight representative tubular injury. Second, slight ACE2 immunostaining observed in Ace2-/- kidney sections is most likely attributable to non-specific background or antibody cross-reactivity rather than residual protein expression. Third, as the mice were euthanized at 4 h post-resuscitation, we did not measure BUN or serum creatinine, since these serologic markers often remain within normal ranges at early time points; histopathological assessment was therefore prioritized as an early indicator of AKI. In addition, histological scoring was based on three fields per sample due to technical constraints, and the relatively small number of animals (three to four per group) may limit the generalizability of our results, although consistent findings across groups support the reliability of our conclusions. Finally, this study focused on the ACE-Ang II-AT1R and ACE2-Ang (1-7)-MasR axes, without assessing the role of AT2R, another RAS component with potential renoprotective effects. Moreover, expression analyses relied solely on immunohistochemistry, which provides spatial resolution but lacks quantitative validation; future work should incorporate complementary approaches such as Western blotting, ELISA, or qPCR. Future studies with larger cohorts and additional methodologies will be required to strengthen and extend our findings.

Collectively, the current investigation showed that hemorrhagic shock induced ACE/ACE2 imbalance in murine kidneys and AKI, whereas ACE/Ang II/AT1R inhibition and MLDL alleviated PHSML-mediated kidney damage and recovered the balance of ACE/ACE2. These results indicate that ACE/ACE2 imbalance is involved in PHSML-mediated kidney injury, which is beneficial for elucidating the mechanism of PHSML-mediated kidney injury and exploring the treatment of kidney injury after hemorrhagic shock in the future.

Conclusions

The imbalance between the ACE-Ang II-AT1R and ACE2-Ang (1-7)-MasR axes is a key mechanism in PHSML-mediated AKI. Targeting RAS may offer a novel therapeutic strategy for AKI following hemorrhagic shock.