gllvm 2.0: fast fitting of advanced ordination methods and joint species distribution models

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Viktor Brygadyrenko

- Subject Areas

- Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, Ecosystem Science, Statistics, Environmental Impacts

- Keywords

- Joint modeling, Maximum likelihood, Multivariate abundance data, Nested design, Ordination, Phylogenetic mixed models, R, Software

- Copyright

- © 2025 Korhonen et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. gllvm 2.0: fast fitting of advanced ordination methods and joint species distribution models. PeerJ 13:e20338 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20338

Abstract

Background

Over the past decade, joint species distribution models (JSDMs) and model-based ordination have emerged as powerful tools for the analysis of community ecology data. Generalized linear latent variable models (GLLVMs) offer a flexible framework for multivariate analysis of a wide range of data types, based on including a small number of latent variables to perform dimension reduction while accounting for residual correlation between species.

Fast estimation methods

The R package gllvm implements a wide range of GLLVMs, with estimation performed via fast approximate likelihood-based techniques; including the recently proposed extended variational approximation, which is applicable to almost any combination of response type and link function. Since its original development and accompanying software paper, the gllvm package has undergone a significant overhaul, consolidating its place as a general framework for joint modeling of community ecology datasets.

Expanded functionalities

Some of the key new features of gllvm include model-based constrained and concurrent ordination methods, capacity to account for nested/hierarchical sampling designs, and (phylogenetic) random effects. On top of this, other notable improvements include a great expansion of the response types that it can handle, enhanced capabilities of GLLVM inference, selection and prediction, and an easier-to-use interface for model fitting.

Introduction

The last decade has seen a push for model-based multivariate methods. Such multivariate methods extend generalized linear models to multiple response variables, usually while incorporating correlation between the responses. The correlation structure is induced by latent variables, hence the models are now commonly referred to as “Generalized Linear Latent Variable Models,” or GLLVMs; although, originally, also the term “Generalized Linear Latent and Mixed Models” has been used (Skrondal & Rabe-Hesketh, 2004), serving to perhaps better highlight the place of the framework inside the wider statistical literature.

Although GLLVMs are potentially applicable to a wide range of biological fields, such as morphometrics or quantitative genetics, most of the developments have instead targeted community ecology; a field of study with a rich history of multivariate method development, such as for classical ordination methods in the '80s and '90s (Kenkel & Orlóci, 1986; ter Braak & Prentice, 1988; Philippi, Dixon & Taylor, 1998). In community ecology, the data consist of observations from an assemblage of potentially interacting species (or other taxonomic groupings), usually collected from a set of samples that are spatially and/or temporally structured. The data are often very sparse, because species often occur at few places due to, for example, environmental filtering (Ovaskainen et al., 2017). The potential to study the effects of biotic filtering acted as the catalyst for increasing popularity of GLLVMs in community ecology—as a technical solution for implementing joint species distribution models (JSDMs) (Pollock et al., 2014; Warton et al., 2015). GLLVMs make for a fast and technically efficient tool for implementing JSDMs, but it is in the application of ordination methods that the latent variable approach fully comes to fruition.

Classically, community ecological studies visualize a small number of latent variables—or, in ecological terms, environmental gradients—to describe patterns of species co-occurrence as well as the (dis)similarity of sites, using either indirect/unconstrained or direct/constrained ordination; for more on this distinction, see ‘Scottish ground beetle dataset’. In such a context, and for sparse data, GLLVMs are the perfect tool for multivariate analysis; by reducing the number of parameters in complex statistical models, the framework greatly facilitates community ecological studies. With a flexibility that is unparalleled by any other ordination method, GLLVMs offer a wide range of opportunities to account for the properties of ecological data by specification of a response distribution and potential inclusion of random effects. The models can straightforwardly be adjusted for good correspondence with the ecological processes under study. Above all, GLLVMs provide a single framework that covers an extremely wide class of models for multivariate analysis (Warton et al., 2015; Niku et al., 2021; Van der Veen et al., 2021; Van der Veen et al., 2023).

GLLVMs have been consistently shown to outperform traditional unconstrained ordination techniques such as principal component analysis and non-metric multidimensional scaling, as well as constrained ordination methods such as redundancy analysis or canonical correspondence analysis (Hui et al., 2015; Van der Veen et al., 2023; Korhonen et al., 2024); the many advantages including e.g., more flexibility in specifying the mean-variance relationship, quantification of uncertainty, and availability of tools for model comparison and diagnostics (Warton, Wright & Wang, 2012). In this article, we provide an overview of the functionality that the gllvm R package has accummulated over the last six years, for fast fitting of advanced ordinations and JSDMs.

The R package gllvm (Niku et al., 2025)—available from the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN)—was originally conceived for fast fitting of multispecies models for community ecology, given that at the time of first development the R software landscape (R Core Team, 2016) was lacking; there were few packages that could feasibly fit JSDMs to large datasets with a non-negligible number of species. Its computational efficiency is due to the implementation of likelihood-based methods coupled with a variety of approximation approaches as developed in Niku et al. (2017b) and Hui et al. (2017). However, since its original development and accompanying software article (Niku et al., 2019b), the functionalities of the package have been greatly expanded, so much so that it can now be considered a general framework for joint modeling of community ecology data. A summary of many of the new features since Niku et al. (2019b) is presented in Table 1, but among these they include: capacity to handle a much wider range of response distributions (see Table A1 in Section ‘Response distributions available in gllvm’ in Appendix), advanced model-based constrained and concurrent ordination techniques, the possibility of accounting for correlations both within and between species due to nested/hierarchical sampling designs, phylogenetic random effects models, and greatly enhanced tools for estimation and statistical inference. The goal of this paper is to present this new, significantly overhauled gllvm package, using a number of worked examples to illustrate how the above new features allow ecologists to fit a myriad of multivariate models to community ecology data.

| Existing features | New features | |

|---|---|---|

| Model type | Linear, independent LVs; Fourth-corner GLLVM | Correlated LVs; Quadratic LVs; LVs informed by covariates; Random slopes for covariates; (Phylogenetic) random effects; Reduced-rank regression |

| Response type | Continuous; Presence-absence; (Overdispersed) counts; Ordinal; Non-negative continuous | Zero-inflated counts; Positive continuous; Percent cover (with 0% and/or 100% records) |

| Community-level row effects | Single fixed/random | Multiple fixed/random; Correlated/structured effects |

| Ordination analysis | Unconstrained; Residual | Constrained; Concurrent; Partial constrained/concurrent |

| Species associations | Residual correlation | Environmental correlation |

| Inference | Analysis of deviance; Confidence intervals for parameters; Diagnostic residual plots | Fixed-effects covariance matrix; Prediction intervals; Variance partitioning; Capacity to handle missing (MAR) data |

| Visualization | Ordination (bi-)plots; Plots of estimated fixed effects; | Uncertainty regions in ordination; Plots of predicted random effects Variance partitioning plot |

| Model fitting methods | Laplace approximation; Gaussian variational approximation | Extended variational approximation; Parallel computation |

Broadly speaking, gllvm can now fit GLLVMs with one or more of the following three parts: (1) latent variables; (2) species effects; (3) community-level row or sample effects. Each of these components corresponds to a specific formula argument in the package, namely

lv.formula

formula

row.eff The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In Section ‘Core components of the package and Estimation’ we briefly review the core components of GLLVMs as well as methods used for fast model fitting, respectively. Section ‘Worked examples’ illustrates some of the key new functionalities of the gllvm package outlined in Table 1, and how they are executed through the aforementioned three formula arguments. Section ‘Discussion’ closes the paper with some discussion and future outlook. Note, that portions of the text have been published as part of a preprint in Korhonen (2025).

Core components of the package

Let yij denote the record for response (species) j = 1, …, m recorded at sample i = 1, …, n e.g., study sites. We may also have information in the form of k environmental or habitat variables for each sample, denoted here as xi = (xi1, …, xik)⊤, and q trait variables for each species, denoted here as tj = (tj1, …, tjq)⊤. Finally, phylogenetic information may be available on the genetic relationship between the species in question, which arises in the form of a m × m correlation matrix.

For joint species distribution modeling, GLLVMs regress the mean abundance μij = E(yij) of the sample-species record against xi and a small number d ≪ m of latent variables, ui = (ui1, …, uid)⊤. As such, (almost) all models available in the gllvm package can be formulated as (1) with the one exception being GLLVMs where species respond unimodally i.e., in a quadratic manner to the latent variables (Van der Veen et al., 2021). In Eq. (1), g(⋅) denotes a known link function e.g., logit/probit-link for presence-absence data and log-link for count data, β0j denote species-specific intercepts, and αi are optional sample- or community-level effects, which can further be treated via a mixed-effects model as , where zi denotes the ith row of a design matrix corresponding to the random effects term. The inclusion of such a model may be as simple as the need to perform a sample-level total abundance standardization, i.e., to account for known differences in sampling intensity across samples (Hui et al., 2015; Warton et al., 2015), or be more sophisticated such as accounting for temporal or spatial correlation between samples. We will also show later how to specify models for αi with (multiple) structured community-level row effects to account for nested/hierarchical sampling schemes, with potentially covariates at different levels of the hierarchy.

Let βj = (βj1, …, βjk)⊤ and γj = (γj1, …, γjd)⊤ denote the full vectors of species-specific coefficients related to the covariates, and species-specific loadings related to the latent variables, respectively. Note the latent variables ui themselves can be thought of as unmeasured environmental variables, or as sample (site) scores in an ordination, capturing the main drivers of species abundances’ or community composition. In the original work of Warton et al. (2015) and Niku et al. (2017a), the latent variables were assumed to be independent across samples and standard normally distributed, ui ∼ Nd(0, I). However, this assumption can now be relaxed in gllvm by assuming a temporal or spatial correlation structure for the latent variables, or by hierarchically regressing the latent variables against the covariates xi; the latter is similar to a typical constrained ordination.

Finally, the species-specific responses to the covariates βj can be regressed against trait covariates tj in order to explain interspecific variation in environmental responses. This is better known in community ecology as fourth-corner modeling (Niku et al., 2021), and can be formulated as (2) where vector βe = (βe1, …, βek)⊤ denotes the main species-common effects for the covariates, k × q matrix Bet denotes the environment-trait interaction matrix also known as the fourth-corner matrix, and species-specific random effects bj = (bj1, …, bjk)⊤ are included and assumed to follow a normal distribution, bj ∼ Nk(0, Σb). To account for species’ non-independence, Eq. (2) can be generalized to incorporate phylogenetic information (Van der Veen & O’Hara, 2024). We note that the fourth corner GLLVM presented here is an extension on the (non-JSDM) fourth corner models of Jamil & ter Braak (2013) and Brown et al. (2014).

Estimation

Fitting GLLVMs is in general a computationally burdensome task. In the literature, many applications have so far employed an Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm (Sammel, Ryan & Legler, 1997; Hui et al., 2015) or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods (Tikhonov et al., 2020b; Pichler & Hartig, 2021). Given the computational intensity of EM and MCMC methods, a more feasible approach is to use methods which approximate the marginal likelihood function in a closed form. We review such methods briefly below, while the more technically oriented reader is directed to Section ‘Further details about likelihood-based estimation in gllvm’ in Appendix for further details.

In the gllvm package, we have implemented a variety of approximation approaches, coupled with automated differentiation techniques (Template Model Builder, Kristensen et al., 2016), that allow efficient model fitting for a plethora of response types and link functions (see Table A1 in Section ‘Response distributions available in gllvm’ in Appendix). In particular, compared with Niku et al. (2019b), a new feature of gllvm is the capacity for nearly universal model fitting, courtesy of the extended variational approximation (EVA) method of Korhonen et al. (2023). EVA presents a solution to a well-known drawback of standard Gaussian variational approximations (VA, e.g., Ormerod & Wand, 2010; Ormerod & Wand, 2012), where a closed-form expression for the variational lower bound is only available for a limited number of response distributions and link functions. For instance, previously in gllvm if one were to fit a GLLVM to say, presence-absence data with logistic link, one had to rely on Laplace’s approximation (LA, Tierney & Kadane, 1986) as closed-form objective function for VA was not available. By contrast, in cases where both LA and a closed-form VA are available e.g., presence-absences using a probit link function, the former has been shown to be both faster and typically more accurate (e.g., Niku et al., 2019a; Korhonen et al., 2023; Korhonen, Nordhausen & Taskinen, 2024).

To overcome the above limitations, EVA applies an additional approximation on the variational objective function in the form of a second-order series expansion. Thus, EVA can be viewed as a blend of the variational and Laplace approximations. Indeed, in the context of machine learning (Wang & Blei, 2013) proposed a similar estimation approach, aptly named delta method variational inference. Critically, the extra approximation step yields closed-form objective functions for practically any response type or link function. At the same time—similar to VA—EVA has been shown to perform well on both simulated and real data, managing to compete and often outperform LA in terms of speed and estimation accuracy (Korhonen et al., 2023; Korhonen et al., 2024; Korhonen, Nordhausen & Taskinen, 2024). In short, EVA has greatly diversified the number of response types and link functions that are available under the variational framework in gllvm, among them the logistic models for presence-absence or percentage data, and most recently the ordered beta distribution of Kubinec (2023) for fitting GLLVMs to sparse percent cover data models. Technical details regarding EVA can be found in Section ‘Extended variational approximations’ in Appendix.

Worked examples

In this section, we provide practical demonstrations using sample code for the overhauled gllvm package, focusing particularly on how to utilize the formula arguments corresponding to the three components of GLLVMs, different types of ordination analysis available, estimation using EVA, and some of the newly supported response types. In Section ‘Scottish ground beetle dataset’, we consider model-based constrained and concurrent ordination in order to extract reduced-rank representations of the environment for zero-inflated overdispersed count data involving lots of covariates. Next, in Section ‘Californian kelp forest data’, we present examples involved with fitting GLLVMs to percent cover data incorporating a nested sampling design, utilizing structured and correlated community-level row effects and latent variables, and leveraging phylogenetic information via a random effects formulation.

The example analyses were conducted in R (v4.4.0, R Core Team, 2016), using the gllvm release v2.0.4, available from https://github.com/JenniNiku/gllvm/releases or https://zenodo.org/records/15720641. Note, that there can exist slight deviations in results depending on the package or R version used. In general, the latest GitHub build can be installed e.g., with devtools (Wickham et al., 2022) by:

> devtools::install_github("JenniNiku/gllvm") From CRAN, the package is available simply with

install.packages("gllvm") Scottish ground beetle dataset

The ground beetle dataset of Ribera et al. (2001) consists of measured counts from m = 68 species of ground beetles collected on n = 87 study sites across the Scottish landscape. Notably, the data contain k = 17 primary environmental covariates, among them e.g.: organic content, soil pH, moisture, canopy height, stem density, flower and fruit biomass, elevation in meters above sea level (m.a.s.l.), and management index score. While it would be possible to fit a multivariate generalized linear model (GLM, Wang et al., 2012) to such data, a useful alternative when the number of covariates is non-negligible and/or when a low-dimensional visual presentation of the species-environment is preferred to investigate a reduced-rank representation of the covariate parameter space (Yee & Hastie, 2003). One may also be interested in ascertaining which environmental covariates drive the gradients of this low-dimensional parameter space, and hence govern community composition (ter Braak & Prentice, 1988; ter Braak & Šmilauer, 2015). The data is included in gllvm and can be loaded with

data("beetle") To address such questions, the gllvm package allows regression models to be formulated for the latent variables and associated species-specific loadings components, also referred to as model-based constrained and concurrent ordination respectively, after Van der Veen et al. (2023). This section provides worked examples to illustrate these new methods, together with the recently added zero-inflated negative binomial response distribution; see also https://jenniniku.github.io/gllvm/articles/vignette6.html for further examples of such ordinations.

Reduced-rank regression and constrained ordination

Consider first the case of using a standard multivariate GLM with only species-specific intercepts β0j, and species-specific coefficients βj. With the k = 17 covariates X in the ground beetle dataset, then the resulting model (3) involves 68⋅(17 + 1) = 1,224 regression coefficients. Given the large number of parameters relative to the information available in the data, a reduced-rank regression (RRR) model (i.e., constrained ordination) significantly reduces the number of parameters to estimate, alleviates potential overfitting issues, and additionally offers the opportunity to construct a lower dimensional visualization (i.e., an ordination). In the constrained ordination, we introduce a k × d matrix of reduced-rank or canonical coefficients B, along with species-specific loading vectors denoted by γj, and impose the following structure on the regression coefficients βj in Eq. (3): (4)

Alternatively, the constrained ordination model resulting from substituting Eqs. (4) into (3) can be written as a special case of the GLLVM in Eq. (1), by defining d-vector latent variables of the form ui = B⊤xi. Note that the identifiability constraints needed in order to fit such a model are quite different from a standard GLLVM where the ui are random effects; see Van der Veen et al. (2023) for technical details. Regardless, the latent variables (or site scores) ui are then said to be constrained by the environmental covariates xi i.e., so that we target only the part of the covariation in the species records that can be filtered by the covariates. In gllvm, such a constrained GLLVM can be fitted as follows:

> X <- scale(beetleEnv) # scale and center the environmental covariates

> ftConstOrd <- gllvm(y=beetle, X=X, family="negative.binomial", num.RR=2). The familiar

summary

plot(summary(ftConstOrd)) Figure 1: Top row: coefficient plots of the reduced-rank approximated species-specific covariate effects corresponding to reproductive biomass (left) and elevation in m.a.s.l. (right), for 34 of the total of 68 species.

Bottom left: model-based constrained ordination of the site scores; longer arrows indicate covariates with the largest relative effect, while arrows for which the 95% confidence interval of the associated slope in B excludes zero, are shown in a darker red color. Bottom right: point estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the canonical coefficients B. The plots are obtained based on fitting a negative binomial GLLVM with d = 2 constrained latent variables and k = 17 covariates.In the code snippet above, the argument

num.RR

randomB

randomB="LV"

randomB="P"

lv.formula

randomB="P"

randomB="single" After fitting the GLLVM, constrained ordination plots (Fig. 1 lower left) along with coefficient plots for species-specific loadings (Fig. 1 top row) can be constructed as follows:

> ordiplot(ftConstOrd, symbols=TRUE, jitter=TRUE)

> coefplot(ftConstOrd, which.Xcoef=c("Reprobiom", "Elevation"), ind.spp=c(1:34)) where the argument

jitter

ind.spp Concurrent ordination

In the constrained GLLVM Eq. (4), it is assumed that the latent variables are driven solely by the measured covariates. This is often unrealistic in practice, and so to simultaneously account for both measured and unmeasured drivers of species covariation we can instead fit a concurrent ordination GLLVM. That is, we can perform simultaneous constrained and unconstrained ordination by incorporating an additional set of “residual” latent variables, (5) where ϵi ∼ N(0, Σ) and Σ = diag(σ2) is a diagonal d × d matrix with variances σ2 as the diagonal elements. Critically, note the same vector of loadings, γj, is related to both rank-d terms: this allows us to alternatively formulate a regression model for the latent variables as ui = B⊤xi + ϵi. To contrast between unconstrained ui’s in Eq. (1), and the fully constrained latent variables in Eq. (4), we refer to the ui’s in Eq. (5) as informed latent variables, meaning they are influenced but not fully constrained by the measured covariates. In the gllvm package, a concurrent ordination GLLVM can be fitted by using the argument

num.lv.c

> ftConcOrd <- gllvm(y=beetle, X=X, family="ZINB", num.lv.c=2, n.init=5) Afterward, the ordination can be visualized with a call to

ordiplot()

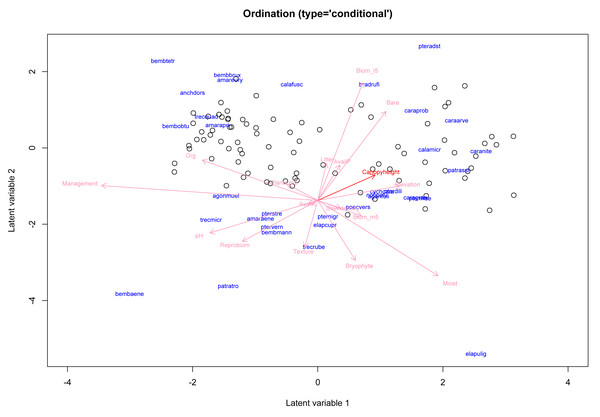

biplot=TRUE Figure 2: Model-based concurrent ordination of the ground beetle dataset, based on fitting a zero-inflated negative binomial GLLVM with d = 2 informed latent variables and k = 17 covariates.

Longer arrows indicate covariates with larger relative effects, while arrows for which the 95% confidence interval of the associated element in B excludes zero in both dimensions are shown in a darker red color—here meaning only the coefficients for canopy height. Estimates for the loadings γj are illustrated using the species’ labels in blue. Note, that the argument ind.spp was used to only plot the loadings for 34 of the species.Being a more complex type of model, concurrent ordination may sometimes benefit from the use of the argument

n.init

n.init=5

starting.val="zero"

optimizer As an aside, the assumption that the two terms in Eq. (5) share the same species-specific loadings γj, can be relaxed in gllvm by combining constrained and unconstrained ordination terms via joint usage of the arguments

num.RR

num.lv Partial concurrent or constrained ordination

In some scenarios, one may wish to include full-rank effects for a subset of the environmental covariates while using a low-rank presentation for the remaining set. This may be thought of as “conditioning” the ordination on some of the measured xi’s, effectively removing their effect from the ordination. Such a “partial ordination” can be constructed in gllvm as in the following example: suppose we wanted to employ full-rank effects for canopy height and reproductive biomass, but a reduced-rank structure for the remaining 15 covariates. Then we can achieve this via the

formula

> ftPartOrd <- gllvm(y=beetle, X=X, family="ZINB", num.lv.c=2,

formula=~Canopyheight + Reprobiom,

lv.formula=~Texture + Org + pH + AvailP + AvailK + Moist

+ Bare + Litter + Bryophyte + Plants.m2

+ Stemdensity + Biom_l5 + Biom_m5 + Elevation

+ Management, randomB="P", n.init=5). In the above, we used

randomB="P"

lv.formula=~(0 + Texture + Org + pH + AvailP + AvailK + Moist

+ Bare + Litter + Bryophyte + Plants.m2 + Stemdensity

+ Biom_l5 + Biom_m5 + Elevation + Management|1). Furthermore, the full-rank effects can be treated as random slopes (e.g., Nussey, Wilson & Brommer, 2007) by instead using

formula=~(0 + Canopyheight|1) + (0 + Reprobiom|1)

formula=~(0 + Canopyheight + Reprobiom|1)

> round(cbind(ftPartOrd$params$LvXcoef,

ftConcOrd$params$LvXcoef[-c(11,15),]), digits=5)

CLV1 CLV2 CLV1 CLV2

Texture 0.01627 0.02919 0.35606 0.38039

Org -0.04452 0.17585 -0.82587 0.35149

pH -0.00795 0.64358 -0.15316 0.79692

AvailP -0.01660 -0.32597 -0.22125 -0.35552

AvailK -0.00001 0.00000 -0.00914 0.07170

Moist 0.06890 -0.24147 1.15432 -0.14245

Bare -0.02380 -0.48900 -0.50632 -0.96130

Litter -0.01490 -0.15635 -0.29376 -0.29661

Bryophyte 0.03446 -0.02939 0.68243 0.19831

Plants.m2 -0.01499 0.02439 -0.26844 0.05678

Stemdensity 0.00834 -0.00030 0.15938 -0.07107

Biom_l5 -0.03822 -0.59255 -0.85311 -1.02737

Biom_m5 0.00003 -0.00001 0.31475 -0.13100

Elevation 0.00892 -0.48093 0.20535 -0.53644

Management -0.06214 1.17037 -1.01267 1.06269. In Section ‘Species correlations due to random covariate effects in Appendix’, we also demonstrate how to use the function

getEnvironCor() To summarize, gllvm now permits a wide variety of GLLVMs based on “mixing-and-matching” various latent variable configuration of the

formula

lv.formula

num.lv

num.RR

num.lv.c

quadratic Zero-inflation and model selection

The model-based ordinations produced in Section ‘Concurrent ordination’ and Section ‘Partial concurrent or constrained ordination’ assumed zero-inflated count distributions for the ground beetle species records (Lambert, 1992; Greene, 1994). In particular, the zero-inflated Poisson and zero-inflated negative binomial distributions are now available in gllvm, and are suited to situations where a standard count model is not capable of explaining the observed rate of zero records for one or more species. Briefly, these distributions are defined by the probability mass function: where p(⋅) denotes the assumed distribution for the (potentially overdispersed) count process i.e., a Poisson or negative binomial distribution, and πj are species-specific parameters controlling the level of zero-inflation for species j = 1, …, m. The choice between the zero-inflated Poisson versus zero-inflated negative binomial models is similar to the choice of the standard Poisson versus negative binomial distributions. That is, the latter (already) accommodates overdispersion by including additional species-specific dispersion parameters ϕj (these can also be shared; see the examples in the following section). We refer to Feng (2021) and references therein for general discussion on zero-inflated models.

Finally, while for model-based ordination it is natural to employ d = 2 to 3 latent variables for the purposes of visualization, gllvm now offers some data-driven procedures for selecting on the final model, whether this is the choice of d, the covariates to retain in various parts of the GLLVM, the usage of zero-inflated versus standard counts distribution, and among other decisions. Specifically, the Akaike, corrected Akaike, and Bayesian information criteria (e.g., Burnham & Anderson, 2002) are available by calling either

AIC()

AICc()

BIC()

num.lv.c | family | num.lv.c | AIC | AICc | BIC | df | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ”Poisson” | 2 | 107,706.96 | 107,726.66 | 109,284.72 | −53,617.480 | 236 |

| 3 | 75,212.17 | 75,248.18 | 77,331.44 | −37,289.083 | 317 | |

| 4 | 53,562.34 | 53,619.31 | 56,209.76 | −26,385.168 | 396 | |

| ”ZIP” | 2 | 69,545.43 | 69,578.48 | 71,577.80 | −34,468.716 | 304 |

| 3 | 49,521.64 | 49,575.39 | 52,095.53 | −24,375.822 | 385 | |

| 4 | 38,601.79 | 38,680.95 | 41,703.82 | −18,836.895 | 464 | |

| ”negative.binomial” | 2 | 18336.45 | 18,369.50 | 20,368.82 | −8,864.225 | 304 |

| 3 | 18,107.78 | 18,161.52 | 20,681.66 | −8,668.888 | 385 | |

| 4 | 17,959.43 | 18,038.59 | 21,061.46 | −8,515.713 | 464 | |

| ”ZINB” | 2 | 18,438.87 | 18,488.94 | 20,925.85 | −8,847.436 | 372 |

| 3 | 18,214.12 | 18,289.42 | 21242.61 | −8,654.058 | 453 | |

| 4 | 18,030.58 | 18,135.93 | 21,587.22 | −8,483.288 | 532 |

In addition to the information criteria, it is advisable to visually inspect the residuals after fitting the model. In gllvm this can be done simply by calling the function

plot() Californian kelp forest data

In the second worked example, we consider a kelp forest dataset from the Santa Barbara Coastal Long Term Ecological Research site (SBC LTER, Reed & Miller, 2023), comprising measurements of percent cover of m = 130 species of marine macroalgae and sessile invertebrates collected between years 2000–2020 along a total of 44 permanent transect lines nested inside 11 observational sites. The data are very sparse, with 88% of the records being zeroes, while the largest recorded cover is 97%. Also, some of the sites were located on islands, while others were located across the coast. The dataset can be accessed within gllvm with the command

data("kelpforest") In contrast to the first example, we can see that kelp forest data involves a nested sampling design, which needs to be accounted for in the process of building a JSDM. More broadly, it is generally assumed that species records collected closer to each other in time and/or space will be more similar to each other. Analogously, species which are closely related in terms of their evolutionary history may respond similarly to a given environment. Through a worked example then, the kelp forest dataset allows us to demonstrate a number of newer features present in gllvm including but not limited to structured models for community-level row effects and latent variables, phylogenetic random effects, and response families for sparse percent cover data.

Structured and correlated community-level row effects

To account for transects nested within sites and years as part of the SBC LTER study, we can fit a GLLVM containing community-level row effects for sampling year, site and transect ID i.e., αi = αyear(i) + αsite(i) + αtran(i) in Eq. (1). In gllvm, accounting for such a nested design is possible via the argument

row.eff

> ftStrucRow <- gllvm(y=Ysess, X=Xenv, num.lv=0, family="orderedBeta",

formula=~logKELP_FRONDSsc + PERCENT_ROCKYsc,

studyDesign=Xenv[,c("SITE","TRANSECT","YEAR")],

row.eff=~(1|SITE/TRANSECT) + YEAR,

method="EVA", link="logit", disp.formula=shapeForm,

setMap=setMap, zetacutoff=c(0,20)). In addition to a fixed effect per sampling year, the syntax

row.eff=~(1|SITE/TRANSECT) + YEAR

studyDesign

disp.formula

zetacutoff

setMap

family="orderedBeta"

method="EVA" To further account for sampling variability, one may instead wish to replace the fixed effect of year with a random effect, where species compositions expressed by a given habitat are more similar to each other for years closer together e.g., the community-level row effects exhibit some sort of autoregressive correlation. Such a temporal correlation structure can be imposed using

row.eff=~(1|SITE/TRANSECT) + corAR1(1|YEAR)

corAR1

corCS

corExp

corMatern

dist Structured and correlated latent variables

Similarly to community-level row effects, the latent variables can also be structured and/or correlated, reflecting, e.g., presumed similarities regarding the unobserved environmental factors driving community composition, between observations in proximity in terms of time or space. For example, if

num.lv=2

lvCor=corAR1(1|YEAR)

> ftCorrLV <- gllvm(Ysess, Xenv, num.lv=2, family="orderedBeta",

formula=~logKELP_FRONDSsc + PERCENT_ROCKYsc,

studyDesign=Xenv[,c("SITE","TRANSECT","YEAR")],

row.eff=~SITE/TRANSECT, method="EVA", link="logit",

disp.formula=shapeForm, lvCor=~corAR1(1|YEAR),

zetacutoff=c(0,20), starting.val="zero", setMap=setMap)

> ftCorrLV$params$rho.lv # estimates for the AR(1) coefficients

rho.lv1 rho.lv2

0.9134419 0.9433707. As can be seen, the estimated autoregressive terms (

rho.lv1

rho.lv2

distLV

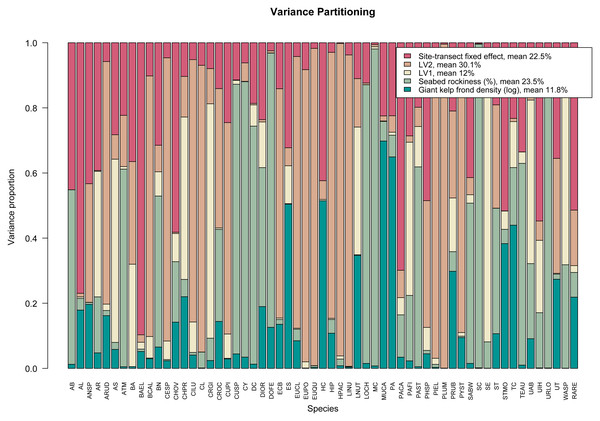

varPartitioning()

plotVP()

> varPart <- varPartitioning(ftCorrLV, groupnames=c("Giant kelp frond

density (log)", "Seabed rockiness (%)", "LV1", "LV2",

"Site-transect fixed effect")) # more descriptive naming

> plotVP(varPart, xlab="Species", las=2, cex.names=0.7, # plot() also works

args.legend=list(cex=0.9), col=hcl.colors(5,"TealRose")). The resulting variance partitioning plot can be seen in Fig. 3. On average, the latent variables specific to sampling year explain ∼42% of the total covariation, the (log) number of giant kelp fronds contribute a relatively small amount except for a few species, while seabed rockiness and site-transect fixed effects each account for approximately 23% of the total species covariation.

Figure 3: Variance partitioning based on fitting an ordered beta GLLVM with d = 2 correlated latent variables (year), fixed structured community-level row effect specific to each site-transect pair, and k = 2 environmental covariates, to the kelp forest data.

Taken together, the two latent variables explain around two fifths of the total species covariation, although the relative contributions of the measured covariates and community-level row effects vary across species.Phylogenetic random effect model

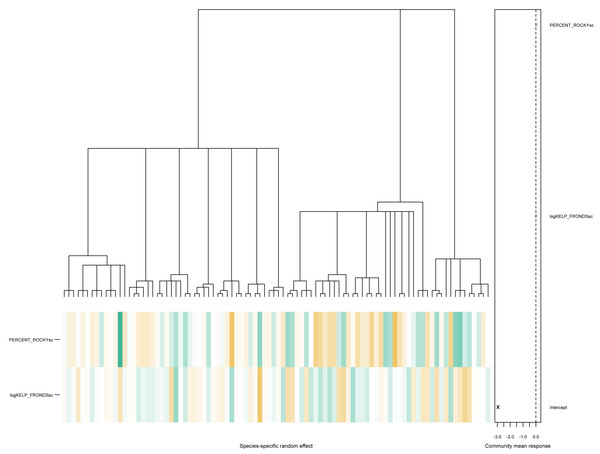

Another feature of the kelp forest data is that it contains taxonomic classifications, allowing us to construct a phylogenetic tree for the species. Following Van der Veen & O’Hara (2024), we demonstrate how phylogenetic random effect GLLMs can be fitted in gllvm. Structurally, such a model builds upon the fourth-corner formulation in Eq. (2) as follows: focusing on the full kelp forest data, consider dummy variables tj which indicate whether species j belongs to the group of sessile invertebrates (tj = 1) or macroalgae (tj = 0).

In a phylogenetic GLLVM then, for covariate l = 1, …, k and given a phylogenetic covariance matrix C, we have (6) where ρl ∈ [0, 1] denotes the phylogenetic signal parameter for the l-th covariate, and noting gllvm allows this to be shared i.e., ρl = ρ for all l = 1, …, k covariates. If the signal ρl is estimated to be close to zero (one), then there is less (more) evidence that species responses are phylogenetically structured. Phylogenetic GLLVMs can be particularly useful when dealing with very sparse data, as rare species can borrow strength from more prevalent species which are closely (evolutionary) related in order to improve their estimation and prediction performance (Ovaskainen et al., 2017; Matsuba et al., 2024). Indeed, recall the kelp forest data is very sparse with over 80% of the species records being exactly zeros, making it a prime use case.

To fit a phylogenetic GLLVM using gllvm, we first have to build the phylogenetic tree and the covariance and distance matrices based on the taxonomic classifications of the species in the data. These are referred to as

tree

colMat

dist

> TMB::openmp(n=parallel::detectCores()-1, autopar=TRUE) where for illustration, we have used the maximum number of threads available minus one.

Suppose we order the species in the kelp forest data according to their distance from the root of the phylogenetic tree (stored in the variable

order

nn.colMat=10

> ftPhylo <- gllvm(y=Yphyl[,order], X=Xenv, TR=Trphyl[order,, drop=FALSE],

formula=~(logKELP_FRONDSsc + PERCENT_ROCKYsc) +

(logKELP_FRONDSsc + PERCENT_ROCKYsc): (GROUP),

randomX=~logKELP_FRONDSsc + PERCENT_ROCKYsc, colMat=list(colMat[order,order], dist=dist[order,order]),

colMat.rho.struct="term", nn.colMat=10, beta0com=TRUE,

method="EVA", link="logit", family="orderedBeta",

n.init=3, disp.formula=shapeForm, zetacutoff=c(0,20),

setMap=setMap, optim.method="L-BFGS-B", num.lv=0)

> summary(ftPhylo)

AIC: 11969.85 AICc: 11970.86 BIC: 13781.04 LL: -5789 df: 196

Informed LVs: 0

Constrained LVs: 0

Unconstrained LVs: 0

Formula: ~logKELP_FRONDSsc+PERCENT_ROCKYsc+logKELP_FRONDSsc:GROUPINVERT

+PERCENT_ROCKYsc:GROUPINVERT

LV formula: ~ 0

Row effect: ~ 1

Random effects:

Name Signal Variance Std.Dev Corr

logKELP_FRONDSsc 0.0032 0.0395 0.1989

PERCENT_ROCKYsc 0.1073 0.0542 0.2327 -0.4436

Coefficients predictors:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

logKELP_FRONDSsc 0.021611 0.034766 0.622 0.534

PERCENT_ROCKYsc 0.052367 0.059213 0.884 0.376

logKELP_FRONDSsc:GROUPINVERT 0.005584 0.047398 0.118 0.906

PERCENT_ROCKYsc:GROUPINVERT 0.112491 0.080530 1.397 0.162. As seen above, there is little evidence of phylogenetic signals in this particular data, with the estimated values of and . The associated community effects from the estimated phylogenetic GLLVM together with the associated tree is visualized in Fig. 4, obtained via the command

phyloplot(ftPhylo,tree) Figure 4: A phylogenetic tree for species in the kelp forest data, together with the predicted species-specific random effects, based on fitting an ordered beta phylogenetic GLLVM model with two covariates and one functional trait.

We conclude this part of the worked example with a few remarks. First, as

num.lv

num.lv=0

colMat.rho.struc="term"

colMat.rho.struct="single"

optim.method="L-BFGS-B"

beta0com=TRUE Models for sparse percent cover data

In the worked examples to the kelp forest data throughout Section ‘Structured and correlated community-level row effects’ to Section ‘Phylogenetic random effect model’, we fitted GLLVMs assuming an ordered beta distribution (Kubinec, 2023) for the species records yij. This was used to accommodate the sparse, percent cover nature of the responses i.e., continuous data that can take any value between and including zero and one, with a large percentage (over 80%) of zeros. The ordered beta GLLVM, together with the beta and hurdle beta hurdle GLLVMs, were introduced in the gllvm package through the recent work of Korhonen et al. (2024), and in doing so addressed an important gap regarding the how to fit JSDMs for multivariate sparse percent cover data. In this section, we briefly review these models and their availability within the package.

In ecology, percent cover data e.g., covers of sessile organisms as in the kelp forest data shown above, plant cover data (Elo et al., 2016; Elo et al., 2024), are typically sparse with a large percentage of zero records. This presents a problem for the standard beta GLLVM i.e., a latent variable model that assumes the responses come from the beta distribution(available in gllvm via

family="beta" As a more systematic alternative for multivariate sparse percent cover data, gllvm fits GLLVMs assuming a hurdle beta distribution for the responses by setting

family="betaH" Yet another alternative available in the gllvm package is the ordered beta distribution, as available via the argument

family="orderedBeta"

zeta.struc="common"

zeta.struc="species" Finally, as used throughout the application above, the argument

zetacutoff

> setMap <- list(zeta=c(1:ncol(Yphyl),rep(NA,ncol(Yphyl)))). This is generally recommended to avoid volatile estimation of the upper cutoff parameter in the absence of exact 100% records in the data. Similar options are available for the dispersion parameters ϕj, using the setting

disp.formula

disp.formula=shapeForm

> shapeForm <- ifelse(Traits$GROUP=="INVERT",1,2) to demonstrate how to share one shared dispersion parameter for invertebrates, and another for seaweed species.

Discussion

In this paper, we presented the newly overhauled gllvm R-package that can be used to address many contemporary questions in modeling community ecology data in a computationally efficient manner. The package has been greatly updated to include a plethora of tools for appropriately modeling and visualizing typical community ecological datasets, a much wider range of distributions for common data types (see also Table A1 in Section ‘Response distributions available in gllvm’ in Appendix), and the capacity to accommodate complex study designs through (for instance) unconstrained ordination at the group-level, incorporating one or more random intercepts to account for pseudo-replication, and by specifying correlation functions across the sampling units due to potential spatial and/or temporal structures. The suite of model-based ordination methods in gllvm has also been extended substantially, including (among others) constrained and concurrent ordination methods that can readily be combined with the community-level effects, ordinations with the aforementioned capabilities to handle nested/hierarchical study designs, and with species-specific effects considered as fixed or (phylogenetically structured) random effects. As demonstrated in this paper, one way in which the last functionality can be useful is when effects need to be “taken out” of the ordination, i.e., the ordination needs to be conditioned on some variable(s). The package also includes other functionalities, e.g., the quadratic response model of Van der Veen et al. (2021) for ordination, which are not covered in this article; these are provided in various vignettes accompanying the package.

gllvm is in continuous development, and there remain many many avenues for further expanding the presented framework and the hence the package. As noted for example in Hui et al. (2023), there remain outstanding challenges in fitting JSDMs to large datasets with many correlated effects (e.g., simultaneous phylogenetic structured species effects and spatio-temporal latent variables, say). Also, the phylogenetic GLLVMs supported by the current version of the package assumes that traits evolve following a Brownian motion. In the future, these models could be extended to support other models for trait evolution, such as the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck Gaussian process model (Uhlenbeck & Ornstein, 1930). Moreover, such models currently rely on a nearest neighbor approximation for computationally scalable estimation, and the authors are currently in the process of adapting the same approximation to scalably fit spatio-temporal GLLVMs (see Tikhonov et al., 2020a for related work using Bayesian estimation). Yet another straightforward but important extension is to handle mixed responses i.e., where the response distributions are allowed to be of mixed type (e.g., Huber, Ronchetti & Victoria-Feser, 2004). Finally, although the gllvm package is able to fit models in parallel, the additional option of being able to utilize GPU resources would further enhane its computational efficiency (see also, Pichler & Hartig, 2021; Rahman et al., 2024).

While this paper’s focus is not a comparison with other packages out there capable of fitting GLLVMs, at this point we do want to acknowledge the increasingly popular glmmTMB R-package (Brooks et al., 2017), which can fit certain types of GLLVMs, although to the best of our knowledge models involving correlated latent variables, correlated random canonical coefficients, phylogenetically structured random slope effects, or quadratic and concurrent GLLVMs have yet to be incorporated into glmmTMB at the time of writing. In the future, gllvm could also learn from glmmTMVB and be extended to include a more general interface to handle zero-inflated and hurdle GLLVMs, although implementation challenges arise if we want to, say, make the latent variables between the zero- and count-component of the model the same or correlated, in order to incorporate correlation between the two model components. Finally, future research could expand the suite of model-based ordination methods available, e.g., by hierarchically modeling the loadings in an ordination (O’Hara & van der Veen, 2024) or by clustering the loadings using a Dirichlet process (e.g., Taylor-Rodríguez et al., 2017; Bystrova et al., 2021). However, likelihood-based estimation of such GLLVMs is (even) more challenging in such extended models, and it may be difficult to find the optimum of the (approximated) likelihood surface due to issues with multimodality and potentially overfitting. Along these lines, gllvm may need to be modified to allow/encourage the use of various penalties to stabilize the fitting process e.g., analogous to the use of weakly informative priors in the Bayesian setting or regularizing penalties to handle complete separation in binary responses (Lemoine, 2019; Clark et al., 2023).