AIMP1: multifunctional regulator in physiology and pathology with therapeutic implications

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Gwyn Gould

- Subject Areas

- Cell Biology, Molecular Biology, Neuroscience, Immunology, Neurology

- Keywords

- AIMP1, Cancer, Immunity associated disorders, Neurological diseases

- Copyright

- © 2025 Yuan et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. AIMP1: multifunctional regulator in physiology and pathology with therapeutic implications. PeerJ 13:e20334 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20334

Abstract

Aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex interacting multifunctional protein 1 (AIMP1), also referred to as p43, serves as an auxiliary factor of the macromolecular aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex. Beyond its classical role in the assembling the multisynthetase complex (MSC) for protein translation, growing evidence has elucidated that AIMP1 plays a pivotal role in regulating immune response, brain function and angiogenesis. Furthermore, accumulating studies have demonstrated that AIMP1 is involved in a spectrum of pathological processes, including cancer, immunity associated disorders, and neurological diseases. Herein, we summarize the current research regarding the functions of AIMP1 under both physiological and pathological conditions, with a particular focus on its therapeutic potential in these diseases.

Introduction

Aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex interacting multifunctional protein 1 (AIMP1) was a critical auxiliary component of the macromolecular aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex. Within this complex, AIMP1 worked in conjunction with two other auxiliary factors, AIMP2 (p38) and AIMP3 (p18) (Park et al., 1999; Liang et al., 2015). AIMP1 contained two leucine zipper motifs (LZ1, LZ2) at its N-terminus, which were important for assembling the human multisynthetase complex (MSC). Its LZ1 interacted with AIMP2’s LZ to form part of the arginyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (RARS1)-AIMP1-AIMP2 heterotrimer. LZ2 formed the complex with RARS1’s LZ2. These dynamic interactions helped to stabilize the complex and support its functions (Kim, Lee & Kang, 2024). All three AIMPs acted as scaffolding proteins to maintain the structural integrity and functional efficiency of the MSC, which was primarily recognized for its essential role in cellular translation (Kim, You & Hwang, 2011; Fu, 2014; Kang et al., 2012; Han et al., 2006). While AIMP1’s canonical function established it as a structural component of the MSC, decades of recent research have uncovered more diverse and impactful biological roles for this protein.

The discovery of AIMP1’s extracellular secretion led to an important insight into its function. As an extracellular molecule, AIMP1 acted as a potent regulator of multiple pathological and physiological processes. It modulated inflammatory responses, angiogenesis and dermal regeneration by acting on target cells such as endothelial cells, macrophages and fibroblasts (Ko et al., 2001; Chang et al., 2002; Park et al., 2002). Beyond these functions, studies have linked AIMP1 to three major areas of biomedical research: cancer, immune associated disorders and neurological diseases. For example, in vivo tumor models have demonstrated AIMP1’s anti-tumor activity (Lee et al., 2006). In autoimmunity research, Aimp1-deficient mice exhibited dendritic cells activation and developed lupus-like autoimmune phenotypes (Han et al., 2007), highlighting its role in maintaining immune homeostasis. Furthermore, inhibiting AIMP1 improved cognitive function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), suggesting a protective effect of AIMP1 suppression in AD (Jang et al., 2017).

These discoveries position AIMP1 at a unique and timely crossroads in biomedical research. Unlike many proteins restricted to a single biological pathway or disease context, AIMP1 spans multiple therapeutic areas, emerging as a potential target for cancers, immune dysregulation-driven diseases and neurodegenerative disorders like AD. Furthermore, advances in structural biology such as crystal structure analysis and receptors analysis have provided new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying AIMP1’s dual functions (intracellular scaffolding and extracellular regulation) (Kim, Lee & Kang, 2024; Kwon et al., 2012). Notably, AIMP1 regulated various signaling pathways, such as the TGF-β pathway (Ahn et al., 2016), which played a crucial role in tumors, immune-related diseases, and neurological diseases (Chen et al., 2018; Chun, Tian & Zhang, 2021; Peng et al., 2022). This suggests that AIMP1 may modulate a common pathway to influence the progression of these diverse conditions, offering new perspectives for developing targeted therapeutic drugs.

Given these advances, a comprehensive review integrating these distinct research lines is urgently needed. This review synthesizes the latest findings on AIMP1’s physiological and pathological functions: physiological roles include regulating immune responses, central nervous system (CNS) function, and angiogenesis, while pathological roles encompass cancer, immunity related diseases, and neurodegeneration. We also identify key knowledge gaps such as AIMP1’s cell-type-specific functions, that must be addressed to advance translational applications. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of AIMP1’s multifaceted roles will lay a critical theoretical foundation for future functional studies and the development of AIMP1-targeted therapeutic strategies, potentially addressing unmet medical needs in oncology, immunology, and neurology simultaneously.

Survey methodology

Engines and search terms used: Literature search was conducted using PubMed and Web of Science databases to evaluate AIMP1’s physiological functions and pathological associations. The search strategy incorporated the following key terms: “Aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex interacting multifunctional protein 1/AIMP1/p43”, “aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex”, paired with functional domains (“immune response”, “neurobiology”, “angiogenesis”) and disease categories (“cancer”, “autoimmunity/immunity related diseases”, “neurological disorders”) to ensure specificity.

Selection criteria required: (1) Peer-reviewed original research articles and reviews focusing on AIMP1; (2) experimental models (in vivo, in vitro, clinical); (3) research with a mechanistic or therapeutic focus (clinical investigation, animal experiments, cell and molecular biology studies). Non-peer-reviewed works and irrelevant studies were excluded.

Methodological rigor was assessed through: (1) For experimental studies-sample size justification, controls and statistical methods; (2) for reviews-citation breadth, bias assessment. Data synthesis prioritized clinical evidence (e.g., biomarker validity, therapeutic targeting) and molecular mechanisms (e.g., cytokine-like activity), with a focus on functions in both physiological homeostasis and pathological processes.

Intended audience: This manuscript is intended to appeal to researchers across diverse fields, including those studying ARS-interacting multifunctional proteins, cancer, immunity-associated diseases and neurological diseases.

AIMP1 in physiological conditions

AIMP1 is a widely expressed scaffold protein that can be secreted and targets various cell types including fibroblasts, endothelial cells and macrophages (Park et al., 1999; Giong & Lee, 2022; Jackson et al., 2011). Classically, it acts as an auxiliary factor to stabilize the interaction between aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) and their corresponding tRNAs (Behrensdorf et al., 2000; Park et al., 1999). AIMP1 is also the precursor of endothelial monocyte-activating polypeptide II (EMAP II), generated via proteolytic cleavage of AIMP1 (Behrensdorf et al., 2000; Kim, Han & Kim, 2014). EMAP II has been shown to play a vital role in facilitating tRNA binding (Kim, Han & Kim, 2014). Accumulating evidence further suggests that AIMP1 is involved in key physiological processes: immune responses regulation, maintenance of brain function and angiogenesis (Park et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2017).

AIMP1 in immune response

Immune responses are primarily characterized by immune cell activation and inflammation (Sun et al., 2020). Elevated EMAP II expression has been observed in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung inflammation and instilling EMAP II in rat increased the number of lung monocytes/macrophages (Journeay, Janardhan & Singh, 2007). In monocyte cell line, AIMP1 was phosphorylated upon LPS challenge (Kim, Han & Kim, 2010). Genetic ablation of Aimp1 rendered mice susceptible to lupus-like autoimmunity (Han et al., 2007). AIMP1 induced the expression of inflammation-related factors such as Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1), TLR2, TLR3 and TLR7 in bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BM-DCs), and modulated the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins (Kim et al., 2011; Park et al., 2002) (Fig. 1). Administering AIMP1 to mice significantly elevated blood levels of IL-1β and TNF-α (Han, Myung & Kim, 2010) (Fig. 1). Collectively, these findings suggest that AIMP1 modulates inflammation and immune cell functions via a “sensing stimuli-recruiting immune cells-cytokine networks regulation” pathway. Its expression, phosphorylated state and regulated cytokine profiles might serve as diagnostic markers for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

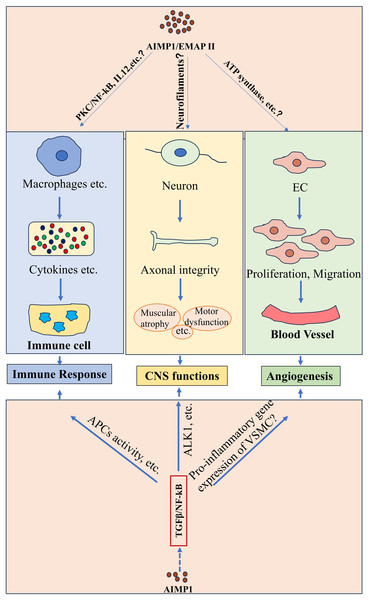

Figure 1: Potential functions of AIMP1/EMAP II in physiological conditions.

AIMP1/EMAP II played important roles under physiological conditions such as immune response, CNS function and angiogenesis. Studies indicated that AIMP1/EMAP II mediated immune response possibly through various of signaling such as PKC/NF-κB signaling. It was indicated that interaction between EMAP II and ATP synthase regulated angiogenesis. In addition, TGFβ/NF-kB signaling was potentially to involve in theses physiological processes regulated by AIMP1.Additionally, AIMP1 elevated the levels of mesenteric lymph node B cells activation markers such as CD19 and CD80. Intravenous administration of AIMP1 in mice upregulated an early activation marker CD69 expression on splenic B cells and enhanced the OVA-specific IgG production, highlighting its role in B cells activation. Further analysis indicated that AIMP1-induced B cells activation was mediated by the protein kinase C (PKC)/NF-κB signaling pathway (Kim & Kim, 2015) (Fig. 1). In macrophages, AIMP1 promoted IL-12 production primarily through NF-κB activation (Kim et al., 2006) (Fig. 1). Notably, AIMP1-stimulated macrophages increased IFN-γ production in keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH)-primed CD4+ T cells. Moreover, the production of AIMP1-enhanced IFN-γ by KLH-primed lymph node cells decreased upon the addition of neutralizing anti-IL-12p40 antibody to cell cultures (Kim et al., 2006), suggesting that AIMP1 may elevate IFN-γ levels in CD4+ T cells via inducing IL-12 in macrophages. These results indicate that AIMP1 modulates B cells and T cells activity through multiple pathways including PKC/NF-κB and IL-12 signaling, coordinating innate and adaptive immunity.

AIMP1 downregulated TGF-β signaling by stabilizing smurf2 (Lee et al., 2008), and AIMP1 downregulation restored chondrogenic properties of degenerated chondrocytes by enhancing TGF-β pathway (Ahn et al., 2016). TGF-β regulated various immune cell functions, such as modulating naive T cell activation, inhibiting Th1/Th2 differentiation, and suppressing B cell proliferation in response to stimuli like immunoglobulin M ligation (Chen, 2023; Sanjabi, Oh & Li, 2017; Tamayo, Alvarez & Merino, 2018). Moreover, TGF-β-NF-κB signaling has been indicated to regulate activity of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and T cells (Ghafoori et al., 2009; Tu et al., 2018), highlighting its critical role in mediating immunity cell activity (Fig. 1). These results collectively suggest that AIMP1 may regulate immunity through the modulation of TGF-β signaling (Fig. 1).

AIMP1 in central nervous system (CNS)

Current evidence identifies AIMP1 as a crucial regulator of brain functions. It interacted with cytoskeletal proteins such as α-tubulin and cingulin, indicating its potential role in regulating the maintenance and remodeling of cellular architecture (Jackson et al., 2011). Notably, Aimp1-deficient mice exhibited profound neurological abnormalities, including axonal degeneration in motor neurons, muscular atrophy, and motor dysfunction. Collectively, these pathophysiological observations underscored the important role of AIMP1 in maintaining axonal integrity and neuronal function within the CNS (Zhu et al., 2009) (Fig. 1).

As noted earlier, AIMP1 modulated TGF-β signaling (Lee et al., 2008), which was critical for CNS homeostasis. TGF-β1 induced cell cycle exit in cortical ventricular zone (VZ) by regulating cell cycle associated protein (Siegenthaler & Miller, 2005). TGF-βs were essential for ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons development (Farkas et al., 2003; Roussa, Farkas & Krieglstein, 2004). Furthermore, TGF-β promoted neurogenesis in neural stem cells and glioblastoma microtube formation via Thrombospondin 1 (Battista et al., 2006; Joseph et al., 2022). TGF-β1 protected neurons from injury via NF-κB activation mediated by the ALK1 pathway (Konig et al., 2005) (Fig. 1). These findings suggest that AIMP1 may influence both the physiological and pathological processes in the brain through TGF-β signaling (Fig. 1).

AIMP1 in angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature (Bhat et al., 2021; Carmeliet & Jain, 2011), plays a vital role in both physiological and pathological conditions (e.g., embryonic development and wound healing), driven by endothelial cells proliferation and migration (Odell & Mannion, 2022; Luo et al., 2023). Earlier studies demonstrated that EMAP II inhibited endothelial cell growth, an effect alleviated by soluble α-ATP synthase, indicating a potential interaction between EMAP II and the α subunit of ATP synthase. Notably, anti-α-ATP synthase antibodies mimicked the EMAP II’s effects on endothelial cells (Chang et al., 2002). These studies suggest that interaction between EMAP II and ATP synthase is pivotal for regulating endothelial cells proliferation and angiogenesis (Fig. 1).

Interestingly, AIMP1 exerted bidirectional effects on angiogenesis depending on its concentration. Low doses promoted endothelial cells migration associated with extracellular signal-regulating kinase (ERK) activation, while high concentrations induced endothelial cells apoptosis accompanied by Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation (Park et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2006) (Fig. 1). TGF-β regulated the proliferation and migration of endothelial and smooth muscle cell (critical for cardiovascular homeostasis) (Goumans & Dijke, 2018), and mediated hypoxia-preconditioned microglia-derived vesicle-induced angiogenesis in stroke mice (Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, transforming growth factor-induced protein promoted angiogenesis mediated by NF-κB via αvβ3 integrins in postnatal lung development (Liu et al., 2021). Furthermore, TGF-β1 suppressed the pro-inflammatory gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC), at least in part by inhibiting the STAT3 and NF-κB pathways (Gao et al., 2018), highlighting the important role of TGF-β/NF-κB signaling in angiogenesis. These data indicate that AIMP1 may modulate angiogenesis through the TGF-β signaling cascade (Fig. 1).

AIMP1 in pathological conditions

AIMP1 in cancer

Cancer is a major global health challenge and the second leading cause of death worldwide (Tewari et al., 2022). Growing evidence shows AIMP1 and its derivative EMAP II play key roles in tumors, with functions varying by cancer type. AIMP1 was found in the conditioned medium of growth hormone (GH)-secreting pituitary adenomas (Bottoni et al., 2005). Notably, AIMP1 levels were higher in smaller GH-secreting pituitary adenomas, indicating a negative link between AIMP1 secretion and tumor size. Further experiments found a negative correlation between AIMP1 secretion and arginyl-tRNA synthetase (RARS) expression (Bottoni et al., 2005). Later research elucidated that RARS overexpression impaired AIMP1 secretion, while proteasome inhibition damaged EMAP II production in cancer cell, underscoring RARS and proteasomes’ role in regulating AIMP1/EMAP II secretion in cancer (Bottoni et al., 2007) (Fig. 2A). Immunohistochemistry analysis showed a marked decrease in AIMP family (AIMP1, AIMP2, AIMP3) proteins levels in gastric and colorectal cancer tissues (Fig. 2B), though these changes did not correlate with clinicopathological features (Kim et al., 2011). In glioblastoma, bioinformatic analysis identified eight genes with strong prognostic value (Cheng et al., 2016). Among these genes, AIMP1, ZBTB16 and FOXO3 were highly expressed in low-risk patients, while IL-6, MMP9, IL-10, CCL18 and FCGR2B were elevated in high-risk patients (Cheng et al., 2016).

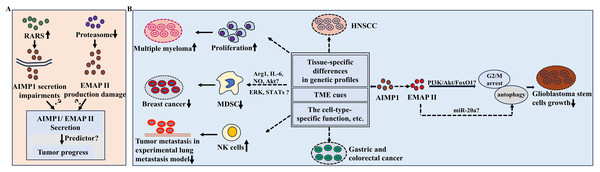

Figure 2: Potential functions of AIMP1/EMAP II in cancer.

(A) RARS overexpression led to the impairment of AIMP1 secretion and proteasome suppression resulted in EMAPII production damage in cancer cell lines. (B) AIMP1 exerted different functions in various cancers. For example, AIMP1 significantly decreased in gastric cancer and colorectal cancer tissues, while increased in HNSCC sample; AIMP1 increased in multiple myeloma and promoted cell proliferation; In mice model of breast cancer, AIMP1 negatively regulated the suppressive functions of MDSC, which was possibly mediated by various of molecules and signaling pathways such as ERK pathway. In addition, AIMP1 inhibited the tumor metastasis through activating natural killer cells in a lung metastasis experimental model. These distinct roles may associate with tissue-specific differences in genetic profiles, TME cues, cell-type-specific function of AIMP1, etc.AIMP1 might also be a prognostic and diagnostic biomarker for HNSC (Li & Liu, 2022). Notably, recent research highlighted the therapeutic potential of targeting immune-related genes including AIMP1 in HNSC patients in immunotherapy triggered by periodontal disease (Fu & Zheng, 2023). In HNSCC, AIMP1 expression increased and was associated with worse survival rate. Furthermore, AIMP1 was more abundant in malignant cells than immune cells, and the high-expression group had lower immune, stroma and microenvironment scores (Li & Liu, 2022) (Fig. 2B), indicating the important roles of AIMP1 in regulating tumor microenvironments (TME). In multiple myeloma, AIMP1 was consistently upregulated, promoting cell proliferation (Fig. 2B). Conversely, knockdown of AIMP1 effectively attenuated multiple myeloma progress (Wei et al., 2022) (Fig. 2B). Bioinformatics analysis revealed cancer patients with elevated AIMP1 levels showed an obvious survival advantage (Liang et al., 2017). In a lung metastasis experimental model, AIMP1 potently inhibited tumor metastasis by activating natural killer (NK) cells (Kim et al., 2017) (Fig. 2B). In mice model of breast cancer, AIMP1suppressed tumor by negatively modulating myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) functions (Hong et al., 2016). It reduced the MDSCs’ suppressive functions by inhibiting Arginase-1 (Arg-1) expression and the production of IL-6 and nitric oxide (NO) (Hong et al., 2016) (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, mechanism analysis indicated that attenuated activation of Akt, ERK and STATs signaling pathways might mediate AIMP1-induced downregulation of MDSCs functions (Hong et al., 2016) (Fig. 2B).

Moreover, it is noteworthy that AIMP1 exerted different functions in various cancers exhibiting tumor-suppressive properties in breast cancer versus pro-malignant in multiple myeloma (Wei et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2016). Such context-dependent functional switching may stem from several interconnected factors (Fig. 2B): (1) Tissue-specific differences in genetic profiles: Breast cells had the potential high basal activity of the estrogen receptor pathway, while the IL-6/JAK-STAT signaling pathway has been a key research focus in multiple myeloma, implying the possible high activity of this signaling pathway (Reiner et al., 1984; Cao et al., 2023; Monaghan et al., 2011). (2) Divergent TME cues, such as differential cytokine profiles between solid breast tumors and hematopoietic bone marrow niches: Breast cancer patients had higher levels of cytokines (including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, etc.), while IL-1β and IL-17A showed no significant difference; in contrast, multiple myeloma patients had significantly higher serum levels of cytokines such as G-CSF, IL-1β and IL-17A than those without multiple myeloma (Demir et al., 2024; Robak et al., 2020). (3) The cell-type-specific functional molecular mechanisms of AIMP1 as supported by prior findings: In breast cancer, AIMP1 targeted MDSCs; in multiple myeloma, AIMP1 interacts with ANP32A to regulate histone H3 acetylation, thereby promoting tumor malignancy (Wei et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2016).

EMAP II also plays important roles in tumors. Previous studies found it inhibited neovascularization in mice, a process key for tumor growth and metastasis. It also slowed breast carcinoma and primary Lewis lung carcinomas growth, underscoring its tumor-suppressive and antiangiogenic effects (Schwarz et al., 1999). In glioblastoma stem cells, EMAP II-mediated growth inhibition involved G2/M arrest and autophagy dysfunction, which were regulated via PI3K/Akt/FoxO1 pathway (Liu et al., 2014) (Fig. 2B). Low-dose EMAP II promoted autophagy in glioma cells by downregulating miR-20a (Chen et al., 2016) (Fig. 2B). Collectively, these cumulative findings provide evidence that EMAP II may modulate glioblastoma progression through autophagy-related pathways (Fig. 2B).

EMAP II enhanced the blood-tumor barrier (BTB) permeability, potentially associated with downregulation of claudin-5, occludin and zonula occluden-1 (ZO-1) (Xie et al., 2010). Another study linked this effect to the RhoA/Rho kinase/PKC-α/β/PP1 pathway and PP1/PP2A-mediated occludin dephosphorylation (Li et al., 2015). Additionally, miR-429 levels were decreased in glioma vascular endothelial cells and glioma tissues. In an in vitro BTB model, EMAP II significantly upregulated miR-429 levels in glioma vascular endothelial cells. Furthermore, miR-429 was found to decrease the phosphorylation levels of p70S6K and S6, contributing to BTB permeability enhancement (Chen et al., 2018). These cumulative findings suggest that EMAP II may regulate cancer growth via miR-429.

Angiogenesis was a prerequisite for solid tumor growth and metastasis (Bhat et al., 2021). TGF-β signaling was critical for angiogenesis. Notably, AIMP1 has been identified as a mediator of TGF-β pathway and angiogenesis (Chang et al., 2002; Jackson et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2021). Future studies should aim to clarify the specific molecular mechanisms and functional significance of AIMP1/TGF-β signaling in angiogenesis regulation.

AIMP1 in inflammation and immune associated diseases

Inflammation is a defensive immune response to diverse stimuli such as tissue injury and infection, triggering a series of biochemical cascades to preserve homeostasis (Woodburn, Bollinger & Wohleb, 2021; Medzhitov, 2008). Accumulating evidence highlights AIMP1’s critical involvement in regulating immune responses and inflammation, with implications for multiple immune-related disorders. For instance, AIMP1 antibody reduced cytokines and inflammatory cells like macrophages, alleviating asthmatic inflammation (Kim et al., 2024), underscoring the critical role of AIMP1 in asthma pathophysiology. Genetic ablation studies in mice further revealed that Aimp1 deficiency exacerbated airway hyperreactivity by promoting TH2 immune responses (Hong et al., 2012) (Fig. 3A). In cocultured system, absence of Aimp1 in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells impaired TH1 polarization of T cells (Liang et al., 2017) (Fig. 3A), indicating the important role of AIMP1 in regulating the activity of dendritic cells as well as the T cells (Kim et al., 2006, 2008, 2019).

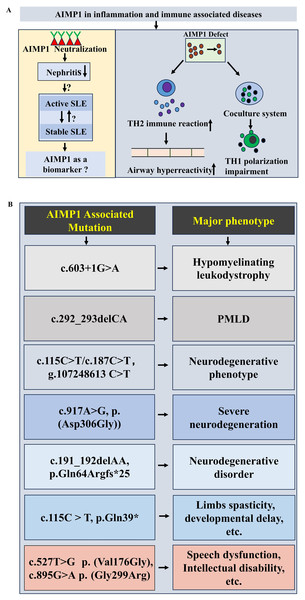

Figure 3: Potential functions of AIMP1 in immune associated diseases and neurological diseases.

(A) Potential functions of AIMP1in immune associated diseases. For example, AIMP1 deficiency induced the enhancement of airway hyperreactivity via increasing TH2 immune reaction. (B) AIMP1 associated m utations in neurological diseases.Notably, clinical investigations have linked AIMP1 to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Median serum AIMP1 levels were significantly higher in SLE patients than in healthy controls. More interestingly, AIMP1 levels were elevated in those with active SLE compared to stable SLE, suggesting a correlation between AIMP1 expression and SLE disease activity (Ahn et al., 2018) (Fig. 3A). Given that lupus nephritis (LN) represented a major SLE complication, studies in (NZB/NZW) F1 mice showed that AIMP1 neutralization markedly attenuated nephritis, implying that targeting AIMP1 could represent a novel immune-modulating strategy for LN (Mun et al., 2019) (Fig. 3A). These findings collectively support AIMP1’s involvement in the pathophysiology of immune-associated diseases, mediated through its regulation of T cell and dendritic cell function.

AIMP1 in neurological diseases

Evidence has established the critical role of AIMP1 in neuronal maintenance and function, with implications for both neurodevelopmental processes and the pathogenesis of diverse neurological conditions. Earlier studies demonstrated that Aimp1 knockout mice developed muscular and motor dysfunction, accompanied by axonal degeneration of motor neuron, implicating the AIMP1’s vital role in preserving axon integrity and neurofilaments assembly (Zhu et al., 2009). Beyond animal models, human genetic investigations have linked AIMP1 variants to multiple neurological disorders. Genetic investigation identified a novel splice site variant, c.603+1G>A in AIMP1 gene, linking it to hypomyelinating leukodystrophy (Quental et al., 2023) (Fig. 3B). Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-like disease (PMLD), classified as hypomyelinating leukodystrophies type 2, has been associated with AIMP1 homozygous mutation (c.292_293delCA) (Georgiou et al., 2017; Singh & Samanta, 2025; Feinstein et al., 2010) (Fig. 3B). AIMP1 mutations also contributed to neurodegenerative phenotypes. A family with a homozygous AIMP1 mutation (g.107248613 C > T, c.115C > T/ c.187C > T ) exhibited neurodegeneration (Armstrong et al., 2014) (Fig. 3B). Exome sequencing revealed a novel AIMP1 gene mutation c.917A>G (p. (Asp306Gly)) associated with severe neurodegeneration symptoms including developmental delays, progressive microcephaly, etc. (BoAli et al., 2019) (Fig. 3B). A rare neurodegenerative disorder was linked to a AIMP1 homozygous mutation (c.191_192delAA, p.Gln64Argfs*25) (Accogli et al., 2019) (Fig. 3B). A homozygous nonsense mutation of AIMP1 (NM_004757.3: c.115C > T: p.Gln39*) was identified in a patient with limbs spasticity, profound developmental delay and failure to thrive (Hori et al., 2021) (Fig. 3B). Additionally, Aimps (including Aimp1) showed dynamic expression pattern in peripheral nerve injury (increased during degeneration but decreased in regeneration phases) (Kim et al., 2019). Notably, AIMP1 variants are also associated with neurodevelopmental disorders independent of neurodegeneration. Mapping and sequencing of consanguineous families with speech dysfunction, development delay and intellectual disability (without neurodegeneration), identified two missense AIMP1 mutations: c.527T>G, p. (Val176Gly) and c.895G>A, p. (Gly299Arg) (Fig. 3B), suggesting a distinct role for AIMP1 in neurodevelopment (Iqbal et al., 2016). Collectively, these results highlight the multifaceted involvement of AIMP1 in both neurodevelopment and the pathogenesis of diverse neurological diseases.

Therapeutic potential of AIMP1 in treating associated diseases

Cancer

The hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/c-mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (c-MET) signaling pathway contributed to melanoma cell proliferation and invasive capacity (Czyz, 2018; Ferraro et al., 2006; Otsuka et al., 1998; Recio & Merlino, 2002). TGF-β signaling was activated by TGF-β binding to its receptors, triggering canonical (SMAD-mediated, regulating target gene expression) and non-canonical (SMAD-independent, involving ERK, JNK, etc., controlling cell metabolism, etc.) signaling cascades (Peng et al., 2022; Deng et al., 2024; Tzavlaki & Moustakas, 2020; Derynck et al., 1985; Derynck & Zhang, 2003; Zhang et al., 1996). While TGF-β signaling has been found to inhibit HGF/c-Met cascades in glioblastoma and suppress tumor metastasis by antagonizing this pathway in tumor epithelial cells (Cheng et al., 2007; Papa et al., 2017). Building on these pathway crosstalk findings, enhancing TGF-β signaling via targeted AIMP1 inhibition may suppress tumor metastasis by modulating HGF/c-MET pathway, offering a potential strategy to mitigate malignant progression (Fig. 4).

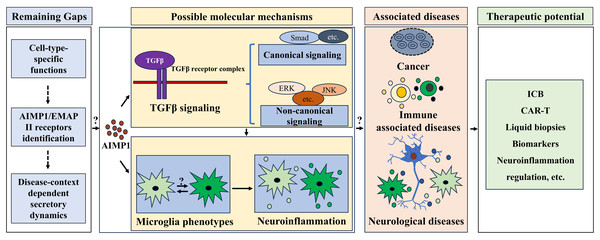

Figure 4: Therapeutic potential of AIMP1 in treating associated diseases.

AIMP1 was involved in regulating TGF-β signaling and microglial phenotypes. Microglial phenotype was important in modulating neuroinflammation. AIMP1 has been indicated to involve in cancer, immune associated diseases and neurological diseases. Thus, AIMP1 might be an effective therapeutic target for treating these diseases via modulating TGF β signaling and microglial associated neuroinflammation, although some gaps including cell-type-specific functions, AIMP1/EMAP II receptors identification, and disease-context dependent secretory dynamics remain unclear.MDSCs were critical for modulating immune response of TME (Hong et al., 2016). Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles acted as key mediators of cancer cells biology and TME remodeling, thereby regulating tumor progression, metastasis, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance (Chen et al., 2023; Kalluri & McAndrews, 2023; Marar, Starich & Wirtz, 2021). Given AIMP1 can be secreted and mediates cell-cell interactions, it is reasonable to speculate that AIMP1 may modulate TME immune responses by regulating tumor-derived extracellular vesicles. Additionally, TME regulated immune checkpoint responses primarily through myeloid cells (e.g., MDSCs) that express checkpoint molecules (e.g., PD-1) and secreted suppressive factors that reshaped the microenvironment to hinder T cell infiltration and activation, mediating response and resistance to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) (Aliazis et al., 2025). AIMP1’s regulation of the MDSCs function in breast cancer (Hong et al., 2016), further suggests its potential role in modulating this myeloid cell-driven ICB response axis such as regulating checkpoint molecules expression (Fig. 4). Moreover, tumor’s immunosuppressive microenvironment exerted an impact on chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) efficacy and safety. Thus, improving the infiltration ability of CAR-T cells and addressing the immunosuppressive reactions in the TME might enhance the anti-tumor outcome (Xia et al., 2024). Notably, in HNSC, it is indicated that AIMP1 overexpression reduced immune infiltration (Li & Liu, 2022), suggesting it might modulate CAR-T efficiency via regulating TME immunosuppressive function (Fig. 4).

Additionally, AIMP1 also served as a dual biomarker in HNSC (Li & Liu, 2022): diagnostic (ROC AUC = 0.759) and prognostic (higher expression correlates with worse survival, with 3/5/10-year time-dependent ROC AUCs = 0.651/0.653/0.756) to stratify patients for targeted therapy. Tumor biomarker discovery supported drug development throughout key phases. Preclinically, it identified predictive biomarkers for responsive populations, assessed prevalence for trial design, and validated models matching human tumor biology; in clinical trials, it aided Phase I companion diagnostics (CDx) development for patient selection, optimized Phase II/III efficacy evaluation and streamlined trials via CDx versatility (McBrearty, Bahal & Platero, 2024). This required rigorous validation of biomarker prevalence, reliable scoring systems, and cross-laboratory reproducibility. For AIMP1, its confirmed pro-malignant role in HNSC underscores the necessity of developing HNSC-tailored CDx, which would support AIMP1-targeted therapy research and translate preclinical findings to clinic, although clinical validation of such therapies’ efficiency remains pending.

Liquid biopsies, as reviewed by Jahangiri (2024) for neuroblastoma, offered a minimally invasive alternative to tissue biopsies by analyzing circulating tumor DNA, circulating tumor RNA, and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from peripheral blood, addressing unmet needs in early detection, minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring, and relapse prediction. Notably, our recent work demonstrated that AIMP1 was detectable in peripheral blood (Wang et al., 2025), positioning it as a promising liquid biopsy marker (Fig. 4). Incorporating AIMP1 into detection panels could enable two critical clinical goals: “longitudinal monitoring of pathway activation” (via circulatory changes reflecting tumor signaling dynamics) and “tumor early diagnosis” (as an early presence indicator). Additionally, AIMP1 may aid targeted therapy selection (identifying AIMP1 inhibitor-responsive patients) and relapse monitoring (detecting AIMP1 elevation before radiological evidence of recurrence), directly addressing core needs improved MRD and relapse detection in high-risk tumors (Jahangiri, 2024). These applications underscore AIMP1’s potential to bridge mechanism research and clinical practice via liquid biopsy.

SLE

As described in section of “AIMP1 in immune associated diseases”, AIMP1 acted as an important regulator of immune cell homeostasis and was implicated in the pathogenesis of immunity related diseases such as SLE (Kim et al., 2011; Kim & Kim, 2015; Ahn et al., 2018). Accumulating evidence pointed to TGF-β pathway impairment in active SLE patients (Rekik et al., 2018). Specially, the TGF-β1 T869C polymorphism was indicated to associate with aseptic necrosis and autoantibodies development in SLE (Wang et al., 2007). Notably, serum TGF-β1 levels were lower in SLE patients with LN than in those without LN, and declining levels correlated with kidney tissues damage and SLE activity progression (Gomez-Bernal et al., 2022; Rashad et al., 2019). Serum TGF-β1 levels were indicated to be an early non-invasive marker for LN diagnosis in SLE populations (Rashad et al., 2019) (Fig. 4). Moreover, TGF-β1 was linked to subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in SLE patients, further highlighting its multifaceted role in disease pathogenesis (Gomez-Bernal et al., 2023). Given these observations, modulating AIMP1 to restore TGF-β pathway homeostasis may represent a promising therapeutic paradigm for autoimmune disorders (Fig. 4), with particular translational relevance for SLE management.

AD

Substantial research confirms the involvement of TGF-β signaling in AD pathogenesis. Genetic association studies linked TGF-β1 polymorphism to AD (Arosio et al., 2007). Cerebrospinal fluid TGF-β1 levels were elevated in AD patients (Zetterberg, Andreasen & Blennow, 2004). Hippocampal distribution of phosphorylated SMADs differed between AD patients and healthy individuals (Ueberham et al., 2006). Functionally, TGF-β1 enhanced microglial amyloid-β (Aβ) clearance (Wyss-Coray et al., 2001). Inhibition of TGF-β signaling increased Aβ production and neuritic degeneration in neuroblastoma cells (Wyss-Coray et al., 2001; Tominaga & Suzuki, 2019; Tesseur et al., 2006). Reducing neuronal TGF-β signaling exacerbated dendritic loss and Aβ accumulation in AD mice (Tesseur et al., 2006). Given that AIMP1 acted as a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling, therapeutic strategies targeting AIMP1 to potentiate TGF-β signaling may represent a novel and promising intervention approach for AD management (Fig. 4).

Neuroinflammation, defined as immune-associated changes within the nervous system, relied on microglia and astrocytes as pivotal immunomodulators (Woodburn, Bollinger & Wohleb, 2021; Glass et al., 2010). As the first line of immune defense and initiators of neuroinflammation, microglia played a critical role in brain disorders driven by neuroinflammation, including AD and Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Woodburn, Bollinger & Wohleb, 2021; Glass et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2023; Chen & Yu, 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Activated microglia exhibited two polarization states: the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype (Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2021). Shifting microglia from M1 to M2 held significant therapeutic potential for neuroinflammation-associated brain disorders (Darwish et al., 2023; Guo, Wang & Yin, 2022; Okada et al., 2022). Microglia-mediated neuroinflammation constituted a fundamental pathological hallmark of AD (Leng & Edison, 2021). For instance, scoparone promoted M2 microglial transition by suppressing TLR4 associated signaling pathway, ameliorating neurodegeneration in an AD rat model (Ibrahim et al., 2023). Notably, exosomes derived from M2 microglia, modulated by light, improved cognition in AD mice (Chen et al., 2023). These findings underscore the importance of maintaining M1/M2 microglial balance in AD progression. Critically, AIMP1 has been identified as a potent inducer of M1 microglial activation via the p38/NFκB and JNK signaling pathways, highlighting its key role in regulating neuroinflammation (Oh et al., 2022).

Beyond AD, M1/M2 microglia dynamics have been implicated in other neurodegenerative disorders such as PD (Guo, Wang & Yin, 2022). Our recent work showed elevated levels of blood AIMP1 in PD. Furthermore, AIMP1 potentiated M1 microglial activation via CD23, ultimately contributing to the dopaminergic neuronal degeneration in PD (Wang et al., 2025), indicating that AIMP1/CD23 signaling played an important role in PD and related neurological diseases. These results established AIMP1 as a critical modulator of microglial polarization, which was also regulated by TGF-β signaling (Zhou, Spittau & Krieglstein, 2012). Thus, targeting AIMP1 to attenuate M1 microglial activity and enhance M2 responses may yield novel therapeutic opportunities for inflammatory neurological disorders (Fig. 4). Additionally, microglia associated neuroinflammation was an important pathological feature in animal models of leukodystrophy (Georgiou et al., 2017). Mutation in AIMP1 gene was linked to PMLD (Feinstein et al., 2010; Biancheri et al., 2011), suggesting that targeting AIMP1-mediated microglial activation could benefit PMLD treatment. However, further mechanistic investigations are needed to systematically delineate the distinct functional roles of different microglial activation states during disease progression, which will advance our understanding and facilitate the development of precisely targeted treatment strategies.

Translational Challenges and Future Directions

Based on the role and therapeutic potential of AIMP1 in the aforementioned diseases, current evidence indicates that AIMP1 presents significant translational value as a therapeutic target, particularly in three key dimensions: therapeutic specificity, biomarker potential and mechanistic elucidation.

Regarding cancer contexts, as comprehensively reviewed by Sonkin, Thomas & Teicher (2024) most tumors possessed multiple oncogenic modifications with a marked level of intra-tumoral and inter-tumoral heterogeneity. Treatments for cancer have evolved from early therapies like surgery and radiation to targeted approaches (Sonkin, Thomas & Teicher, 2024). AIMP1’s pathological functional switching (tumor-suppressive in breast cancer, pro-malignant in multiple myeloma) might be associated with dysregulation of its physiological roles in angiogenesis, TME modulation, and TGF-β signaling. The key challenge lies in translating this context-dependence into precision medicine: preclinical data showed AIMP1 interacts with MDSCs in breast cancer and ANP32A in multiple myeloma, while clinical studies linked its overexpression to poor prognosis in HNSCC. To advance therapy, research must validate cancer-type-specific biomarkers and develop companion diagnostics (CDx) that stratify patients for AIMP1-targeted interventions.

In the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, the alterations in AIMP1 levels indicated a correlation with the disease course of SLE (Ahn et al., 2018). This, to some extent, supported its potential as a diagnostic marker for SLE, albeit requiring further validation in large cohorts. Additionally, in neurological diseases, translational barriers center on stage-specific mechanistic clarity: its precise role in neurodevelopment (such as speech dysfunction from missense mutations) and neurodegeneration (Aβ clearance impairment in AD), yet the timing of therapeutic intervention (e.g., targeting AIMP1 before irreversible neuronal loss) remains undefined. Prioritizing phase-specific analyses of AIMP1-TGF-β pathway or AIMP1-microglial polarization pathways will be key to identifying actionable therapeutic windows.

Across disease areas, shared gaps persist that tie to AIMP1’s basic biology: defining how its cell-type-specific functions (e.g., neuronal vs. immune cell dynamics) shape pathology, identifying definitive AIMP1/EMAP II receptors (essential for decoding extracellular signaling), and mapping secretory regulation (e.g., proteasome/RARS control in tumors vs. inflammatory tissues). Resolving these via integrated clinical and preclinical studies will enable translating AIMP1’s therapeutic potential into precise treatments across oncology, immunology, and neurology.

Conclusions

As a critical auxiliary component of the macromolecular aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex, AIMP1 plays an important role in protein translation. Accumulating evidence established its involvement in diverse diseases such as cancer, immune dysregulation syndromes and neurological disorders, potentially mediated by regulating the TGF-β pathway, immune responses, and neuroinflammation. Nevertheless, key knowledge gaps regarding AIMP1 persist, particularly in terms of its specific functions across diverse cell types, the identification of its receptors, and the context-dependent secretory dynamics of AIMP1 in pathological settings (Fig. 4). Future studies (including comprehensive clinical and animal research) focusing on these unresolved issues will pave the way for developing targeted therapeutic strategies, offering precise treatments for AIMP1-associated diseases across oncology, immunology, and neurology.