Minos-mediated transgenesis in the pantry moth Plodia interpunctella

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Rodrigo Nunes-da-Fonseca

- Subject Areas

- Entomology, Genetics

- Keywords

- Minos, Transgenesis, Pantry moth, Lepidoptera

- Copyright

- © 2025 Shodja et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Minos-mediated transgenesis in the pantry moth Plodia interpunctella. PeerJ 13:e20249 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20249

Abstract

Transposon-mediated transgenesis has been widely used to study gene function in Lepidoptera, with piggyBac being the most commonly employed system. However, because the piggyBac transposase originates from a lepidopteran genome, it raises concerns about endogenous activation, remobilization, and silencing of transgenes, thus questioning its suitability as an optimal tool in Lepidoptera. As an alternative, we evaluated the dipteran-derived Minos transposase for stable germline transformation in the pantry moth, Plodia interpunctella. We injected syncytial embryos with transposase mRNA, along with donor plasmids encoding 3xP3::EGFP and 3xP3::mCherry markers of eye and glial tissues. Across multiple experiments, we found that G0 injectees could transmit Minos transgenes through the germline even in the absence of visible marker expression in the soma, and that large mating pools of G0 founders consistently produced transgenic offspring at efficiencies exceeding 10%. Using these methods, we generated transgenic lines with a dual expression plasmid, using 3xP3::mCherry for driving red fluorescence in eyes and glial tissues, as well as the Fibroin-L promoter expressing the recently developed mBaoJin fluorescent protein in the silk glands. This demonstrated the feasibility of screening two pairs of promoter activity in tissues of interest. Collectively, these results—along with previous findings in the silkworm Bombyx mori—demonstrate that Minos achieves robust germline integration of transgenes in Lepidoptera, offering a valuable pathway to the genetic modification of species where the remobilization or suppression of piggyBac elements might be rampant.

Introduction

There is growing interest in developing new laboratory model systems and methods for the study of functional genomics in Lepidoptera, an enormous insect lineage where the silkworm Bombyx mori has been a focal species for the study of gene function. The pantry moth Plodia interpunctella is a pest of stored food with life history traits that make it suitable for economical and long-term maintenance of genetic lines. We and others have previously established methods for non-homologous repair mediated Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) mutagenesis, CRISPR short edits based on homologous recombination, and piggyBac-mediated transgenesis in this organism (Bossin et al., 2007; Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022; Heryanto et al., 2022; Shirk et al., 2023). So far, we have failed to insert a transgenic cassette of several kilobases using CRISPR-related techniques based on homologous repair and non-homologous plasmid insertion. Transposon-based random insertion of transgenes thus remains a valuable method in Plodia, and we expect that the further optimization of such methods will potentiate fundamental studies of lepidopteran biology, notably because the reagents used in these experiments—the source of transposase mRNA and the transgene donor plasmids—are easy to transfer to new species without modification.

One potential limitation of transgenesis in Lepidoptera as currently implemented, however, is that the favored piggyBac transposase originated from a lepidopteran species, the cabbage looper Trichoplusia ni (Fraser et al., 1985). Several distant lepidopteran species are known to harbor nearly identical piggyBac elements in their genomes, raising concern that their endogenous activity could elicit remobilization of newly inserted cassettes (Zimowska & Handler, 2006; Wu et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010). Consistent with these potential issues, two studies documented that piggyBac transgenes can be remobilized in Bombyx and hinder the interpretability of reporter assays (Wang et al., 2015; Jia et al., 2021). In addition, certain species could have evolved silencing mechanisms to limit piggyBac element invasion and transmission (Zimowska & Handler, 2006), as characterized in Drosophila flies that evolved resistance to P-element transposons (Khurana et al., 2011; Teixeira et al., 2017; Moon et al., 2018). Given these potential concerns, it is important to assess whether transposons originating from more distant lineages work with a similar efficiency in Lepidoptera.

Here we investigated the suitability of an alternative transposon-based method using the Minos transposase. Minos is a Tc1/mariner element derived from the dipteran Drosophila hydei that has has been widely used for transgenesis in insects (Franz & Savakis, 1991; Loukeris et al., 1995; Loukeris et al., 1995; Kapetanaki et al., 2002; Pavlopoulos et al., 2004; Metaxakis et al., 2005), and other invertebrates (Zagoraiou et al., 2001; Hozumi et al., 2010; Kontarakis & Pavlopoulos, 2014; Jackson et al., 2024; Kuo et al., 2024). Importantly, a previous study found that the Minos transposase can mediate efficient germline integration in Bombyx embryos when delivered as an in vitro transcribed mRNA (Uchino et al., 2007). We transferred these methods to Plodia, observed efficient germline transmission of two plasmids, validated the expression of three fluorescent markers, and overall, confirmed that Minos can mediate stable transgenesis in another lepidopteran laboratory system. We discuss strategies for the rapid generation of transgenic lines in Plodia and provide detailed methods to facilitate the use of this technique in other species.

Materials and Methods

Portions of this text were previously published as part of a preprint (Shodja, Livraghi & Martin, 2025). The Institutional Biosafety Committee at the George Washington University administered the approval of Plodia rearing and transgenesis protocols in the Martin lab (protocol #IBC-24-261).

Plasmids

The pMi[3xP3::EGFP-SV40] donor plasmid and the Minos transposase transcription template plasmid pBlueSKMimRNA (Pavlopoulos et al., 2004) were sourced from Addgene (RRID:Addgene_102540; RRID:Addgene_102535). The pMi[3xp3::mCherry-SV40, Plodia-FibL::mBaojin-P10] plasmid was produced using Gibson Assembly, by replacing the EGFP-SV40 section of pMi[3xP3::EGFP-SV40] with a synthetic (mCherry-SV40, FibL::mBaoJin-P10) gene fragment synthesized by Twist Bioscience, and is available from Addgene (RRID:Addgene_240410). The FibL promoter sequence corresponds to 1 kb of sequence upstream of the P. interpunctella FibL gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/?term=LOC128678647).

Preparation of Minos transgenesis reagents

Plasmids were amplified in 50 mL liquid cultures of Luria-Bertani broth with 100 μg/mL Ampicillin, and plasmid DNA was purified with the ZymoPURE II Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Cat# D4200). Plasmids were eluted in 120 μL of elution buffer, yielding concentrations >4,800 ng/μL of plasmid DNA.

To produce Minos transposase mRNA, the pBlueSKMimRNA plasmid was linearized using the NotI-HF restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), purified by gel extraction using the Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA), and further purified using the Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator-25 kit with an elution volume of 13 μL of DNA elution buffer. Subsequently, the HiScribe T7 ARCA mRNA with tailing kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) was used for transcription and capping of Minos transposase mRNA, followed by purification using the MEGAClear Transcription Clean-Up Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The purified mRNA was eluted in 50 μL of the provided elution buffer, which was pre-heated to 65 °C and incubated on the filter column for 10 min in a 65 °C oven. After quantification with Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), the transposase mRNA was divided into >520 ng/μL one-time use aliquots and stored at −70 °C.

Injection mixes were freshly prepared before injection and consisted of 400 ng/μL Minos transposase mRNA, 200 ng/μL donor plasmid, and 0.05% Phenol Red (1:10 dilution of a 0.5% cell-culture grade Phenol Red solution; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), brought to a 5 μL final volume with 1x Bombyx injection buffer (pH = 7.2, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM Na2HPO4, 5 mM KCl).

Plodia strain

The white-eyed wFog laboratory strain of Plodia interpunctella was used to facilitate the screening of 3xP3-driven fluorescence in pupal and adult eyes (Heryanto et al., 2022; Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022). This strain consists in the genome background of the Dundee strain (NCBI genome accession GCA_001368715.1), into which a white gene c.737delC mutation originating from the Piw3 strain (NCBI genome accession: GCA_022985095.1) was introgressed during two generations of backcrossing and several rounds of sib-sib inbreeding (Heryanto et al., 2022).

Plodia husbandry

The wFog strain and the transgenic broods were reared in the laboratory from egg to adulthood in an incubator set at 28 °C with 40–70% relative humidity and a 14:10 h light:dark cycle, following methods made available via the Open Science Framework repository (Heryanto et al., 2025). Briefly, egg laying was induced by CO2 narcosis of adult stocks in an oviposition jar, and a weight boat containing 10–13 mg eggs was placed in a rearing container containing 45–50 g of wheat bran diet with 30% glycerol (Table S1). This life cycle spans 29 days from fertilization to a reproductively mature adult stock at 28 °C.

Microinjection of Plodia syncytial embryos

The general procedure for microinjection as well as a list of suggested equipment is available online (Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022) and summarized below. Minos capped mRNA and the donor plasmid were mixed into a 5 μL aliquot (400:200 ng/μL mRNA:DNA) and kept on ice shortly before the procedure. Eggs were collected in an oviposition jar following CO2 narcosis of a stock of wFog strain adults, aligned on parafilm, and microinjected between 20–50 min after egg laying (AEL) using borosilicate pulled glass needles and an air pressure microinjector. Eggs were then sealed with cyanoacrylate glue and left to develop at 25 °C or 28 °C in a closed tupperware with a wet paper towel.

Fluorescent screening equipment

All life stages were screened under an Olympus SZX16 stereomicroscope equipped with a Lumencor SOLA Light Engine SM 5-LCR-VA lightsource, mounted to a trinocular tube connected to an Olympus DP73 digital color camera. Fluorophore expression was observed using Chroma Technology filter sets ET-EGFP 470/40× 510/20m green fluorescent protein (GFP) and AT-TRITC-REDSHFT 540/25X, 620/60m red fluorescent protein (RFP). Autofluorescence patterns are shown for uninjected individuals, using the GFP and RFP filter sets and exposure times consistent with the other images in this study (Fig. S1). It is worth adding that a yellow fluorescent protein filter set (e.g., Chroma ET-EYFP 500/20× 535/30m) reduces cuticle autofluorescence and can be advantageous to use in addition to a GFP filter set for screening EGFP and mBaoJin expression. For small mosaic clones, or weak fluorescent signals, the YFP filter on its own may lead to false negatives.

Screening of embryos and first instars larvae

To obtain synchronized embryos, mated adults are anesthetized by CO2 narcosis and transferred to a glass jar with a mesh lid insert (Heryanto et al., 2025). CO2 exposure triggers egg release in Plodia, and embryos are collected after 2–4 h, transferred to a glass petri dish, and incubation at 28 °C and saturating humidity (e.g., in a sealed tupperware with a wet paper towel), until time of screening. The screening of embryos is most convenient when using crosses performed in relatively large pools, for example with more than 10 mated females. Screening of transgenic embryos is optimal at 68–74 h AEL if incubated at 28 °C, a time window where 3xP3-driven fluorescence in presumptive glia and ocelli is discernible in the larval head and body. Earlier times of screening show weaker fluorescence and confounding signals, likely due to the episomal expression of residual plasmids in large vitellophages (Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022). Hatching occurs at 78–82 h AEL in uninjected embryos and can be delayed by up to 12 h in G0 embryos, due to injection stress.

Screening of pupae and adults

The screening of pupae is ideal to verify the transgenic status of imagos in preparation of a new generation, and can also be the method of choice when screening offspring from small crosses (less than 10 females), where isolating synchronized embryos by CO2 narcosis is not optimal. As pupae can be difficult to isolate from the larval diet, it is helpful to add strips of cardboard to larval containers that contain fifth instar larvae, as the corrugations within this material are the preferred pupation site that facilitates the collection of pupae (Shim & Lee, 2015). Pupae are then isolated from these lodges, as well as from those located within the diet, transferred to tissue culture dishes for screening and sex sorting, and subsequently combined according to the cross design in fresh containers to allow adult emergence and mating prior to initiating the next generation. Fluorescent and brightfield images of pupae were acquired using the same fluorescent microscopy set-up using the Olympus DP74 camera, and overlaid using the Screen blending mode in Adobe Illustrator. Brightfield images of transgenic G2 adult eyes (Fig. 1F) were taken using a Keyence VHX-5000 digital microscope. Pupal stages (%, Figs. 1C, 2G) were estimated based on eye, wing, tarsal, and cuticle pigmentation (Zimowska et al., 1991). Adult moths can be screened in a petri dish held on ice to limit moth activity.

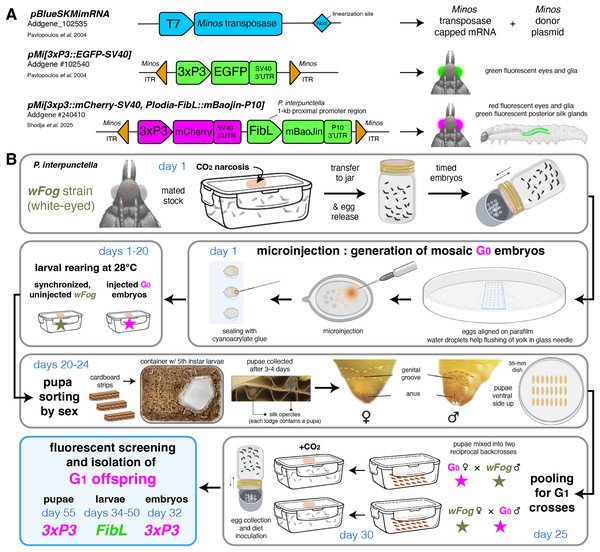

Figure 1: Transgenic Plodia carrying the 3xP3::EGFP cassette via Minos-mediated transgenesis.

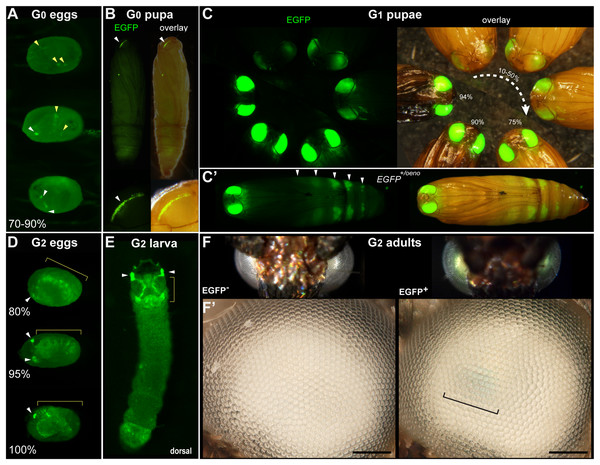

(A) G0 eggs from injections of the donor plasmid pMi[3xP3::EGFP] and Minos transposase mRNA. Three examples of 3xP3 activity are shown at 70–90% of embryonic development. Effects are distinct from uninjected controls (Fig. S1). (B) Example of a mosaic 3xP3::EGFP expression in a G0 pupal eye. Right panels depict an overlay of EGFP and brightfield images taken separately. (C) Non-mosaic expression of EGFP in G1 pupal eyes. EGFP intensity increases with the developmental stage of the pupae. Pupal stages (%) were estimated based on eye, wing, tarsal, and cuticle pigmentation (Zimowska et al., 1991). (C’) Expression of the EGFP +/oeno allele, characterized by ectopic signal in abdominal segments (white arrowheads) in addition to the eyes. This ectopic activity marks oenocytes (Fig. S2) and was stable across subsequent generations. (D) G2 embryos show expected 3xP3::EGFP activity in the developing ocelli and presumptive glia. (E) pMi[3xP3::EGFP] expression in a first instar G2 larva shows strong activity in head glia and lateral ocelli. (F–F’) Adult G2 individuals positive for 3xP3::EGFP have green eyes under normal white light, due to strong EGFP expression. Comparison of an G2 adult negative (left) and positive (right) for 3xP3::EGFP under white light illumination and without fluorescence filters (F’: magnified, lateral views of corresponding eyes). Bracket: visible green tint in inner retina. White arrowheads (A–B, D–E): fluorescent eye/ocelli (white). Yellow arrowheads and brackets (A–B, D–E): fluorescent glial tissues. Scale bars: F’ = 100 μm.Figure 2: Tissue-specific activities of the [3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaojin] transgene following Minos -mediated integration.

(A) Mosaic expression of 3xP3::mCherry in G0 embryos, following injections of the donor plasmid pMi[3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaojin] and Minos transposase mRNA. Three examples of 3xP3 activity are shown at 75-85% of embryonic development. Arrowheads indicate 3xP3 specific signals in glia and ocelli. (B–B’) Example of a mosaic [3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaojin] expression in a G0 pupal eye. Arrow (B’): deeper non-retinal expression of 3xP3 in the optic lobe. (C) Dorsal views a G1 embryo (95% stage), showing expected 3xP3::mCherry activity in the developing ocelli and presumptive glia. Brightfield, and autofluorescence in the GFP channel are added underneath. No mBaoJin is detectable in embryos. (D) Aspect of FibL::mBaoJin green fluorescence in silk glands, directly visible through the dorsal epidermis of a G1[mCherry+] first instar larva. (E) FibL::mBaoJin expression in a G1 fifth instar larva in segments A3-A5. (F-F’) Dissected silk gland of a G1 fifth instar larva expressing FibL::mBaojin in the Posterior Silk Gland (green). F’ panels show confocal stacks of the curved region around the MSG-PSG boundary (dotted line). DAPI counterstaining (blue) highlights polyploid branched nuclei (pbn), in the layer of large cells that surround the gland lumen (lu). The mBaojin signal is strongest in the PSG lumen and extends into the MSG lumen. (G–G’) Expression of 3xP3::mCherry in G1 pupal eyes, increasing with the developmental stage of the pupae (shown as %). White arrowheads (A–D): fluorescent eyes/ocelli. Yellow arrowheads and brackets (A, C–D): fluorescent glia. Scale bars: F = 500 μm; F’ = 100 μm.Characterization of silk gland fluorescence

The FibL::mBaojin transgene drives strong silk gland fluorescence visible directly through the cuticle of all larval instars. The silk glands of a G2 FibL::mBaojin transgenic fifth instar larva were dissected, fixed, and mounted following a previously described procedure (Alqassar & Martin, 2025), and imaged on an Olympus SZX16 fluorescence stereomicroscope, as well as on an Olympus FV1200 confocal microscope mounted with a 20x objective.

Results

Somatic and germline transformation of a test Minos donor plasmid

To test for the efficacy of Minos-mediated transgenesis in Plodia embryos, we initially microinjected 1,317 eggs between 20–50 mins AEL, with the pMi[3xP3::EGFP-SV40] test donor plasmid (Pavlopoulos et al., 2004). This injection time window, as well as the microinjection technique and rearing conditions were comparable to our previous experiments using the Hyperactive piggyBac transposase (HyPBase) in Plodia (Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022). The injection mix consisted of capped poly-A tailed Minos mRNA, mixed with a donor plasmid for the integration of the 3xP3::EGFP transgenesis marker cassette.

We conducted three injection trials using the pMi[3xP3::EGFP-SV40] plasmid. All three attempts resulted in detectable activity in a portion of G0 embryos and pupae. Embryonic activity of 3xP3::EGFP, observed as of bright fluorescent puncta in the presumptive glia and larval ocelli (Thomas et al., 2002; Bossin et al., 2007; Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022; Pearce et al., 2024), was respectively detected in 10.3%, 7.8% and 4.3% of G0 embryos in Experiments #1, #2 and #3 (Fig. 1A, Table 1). Pupal activity of 3xP3::EGFP, consisting of bright fluorescent stripes of expression in the pupal eyes of the wFog white-eyed strain used here (Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022), was observed in 7.1%, 15.7%, and 16.7% of pupae in Experiments #1, #2 and #3 (Fig. 1B, Table 1). Overall, these data indicate that Minos transposase can drive transgene insertion into the genome of somatic cells.

| Plasmid | Experiment (injection session) |

G0 embryos | G0 pupae | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injected | 3xP3 somatic transf. | % somatic transf. | Total | 3xP3 somatic transf. | % somatic transf. | ||

| pMi[3xP3::EGFP] | #1 | 341 | 35 | 10.3% | 14 | 1 | 7.1% |

| #2 | 696 | 54 | 7.8% | 51 | 8 | 15.7% | |

| #3 | 280 | 12 | 4.3% | 24 | 4 | 16.7% | |

| Sub-total | 1,317 | 101 | 7.7% | 89 | 13 | 14.6% | |

| pMI[3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaoJin] | #4 | 456 | 13 | 2.9% | 77 | 1 | 1.3% |

| #5 | 396 | 82 | 20.7% | 32 | 5 | 15.6% | |

| Sub-total | 852 | 95 | 11.2% | 109 | 6 | 5.5% | |

| Total | 2,169 | 196 | 9.0% | 198 | 19 | 9.6% | |

Note:

transf, transformants with detectable 3xP3 activity.

Next, we assessed whether Minos could efficiently transpose the test insert into the germline, and enable its transmission over subsequent generations. Following Experiment #1, we in-crossed all the 14 G0 adults by pooling them for random mating and rearing in a single container. We recovered 250 G1 pupae, 23.6% of which showed transgene activity (Fig. 1C, Table 2). Following Experiment #2, we similarly in-crossed 41 G0 adults, but then directly screened embryos instead of pupae. This in-cross generated 470 G1 embryos, of which 11.5% were transgenic (Table 2). It is worth noting that in these two crosses, 13 out of 14 of the G0 founders from Experiment #1, and all of the G0 founders from Experiment #2, lacked a detectable somatic activity of 3xP3::EGFP at the pupal stage. For comparison, we out-crossed 5 EGFP+ G0 males from Experiment #2 to 10 females from the uninjected wFog strain, and obtained 10.6% transgenic embryos out of 113 G1 eggs. In summary, both G0 negative and positive individuals can be used as founders for germline transmission of Minos transgenes, as somatic transformants do not necessarily reflect whether germline transformation has occurred.

| Experiment | Gen. | Cross design | Embryos | Pupae | Chi-2: 50% ratio, single insert |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | EGFP+ ocelli & glia |

Total screened |

EGFP+ eyes | EGFP+ oenocytes | ||||

|

pMi[3xP3::EGFP] Experiment #1 |

G1 | Random in-cross of 14 G0 founders (1 EGFP+, 13 EGFP−, sexes n.d.) |

– | – | 250 | 59 (23.6%) | 10 (4%) | n.a. |

| G2 | 4 ☿ wFog × 1 G1 [EGFP+] ♂ | – | – | 24 | 17 (70.8%) | 0 | n.s. | |

| 1 G1 [EGFP+] ☿ × 4 G1 [EGFP−] ♂ | – | – | 104 | 70 (67.3%) | 0 | p < 0.01 | ||

| 4 G1 [EGFP−] ☿ × 1 G1 [EGFP+/oeno] ♂ | – | – | 80 | 43 (53.7%) | 43 (53.7%) | n.s. | ||

| 4 G1 [EGFP−] ☿ × 1 G1 [EGFP+/oeno] ♂ | – | – | 75 | 40 (53.3%) | n.d. (<40) | n.s. | ||

| G3 | 1 G2 [EGFP−] ☿ × 4 wFog ♂ | – | – | 117 | 60 (51.3%) | 0 | n.s. | |

| 1 G2 [EGFP+/oeno] ☿ × 4 wFog ♂ | – | – | 139 | 64 (46.0%) | 64 (46.0%) | n.s. | ||

| G4 | random in-cross of 60 G3 [EGFP+] | – | – | 30* | 30 (100%) | 0 | n.a. | |

| random in-cross of 64 G3 [EGFP+/oeno] | – | – | 70* | 70 (100%) | 70 (100%) | n.a. | ||

|

pMi[3xP3::EGFP] Experiment #2 |

G1 | random in-cross of 41 G0 founders: 29 EGFP− ☿ x 12 EGFP− ♂ |

470 | 54 (11.5%) | × | – | – | n.a. |

| 5 G0 [EGFP+] ♂ x 10 ☿ wFog | 113 | 12 (10.6%) | × | – | – | n.a. | ||

Notes:

Only Experiments #1–2 are shown here, as G0 injectees from Experiment #3 were not crossed to a next generation. The last column indicates the p-value of Chi2 tests for difference to a 50% distribution. Results are in bold for back-crosses to wFog, where a 50% segregation is expected from a single-insertion in the transgenic donors.

Gen, generation; n.a, not applicable (a 50% distribution is not expected in these crosses); n.d., not determined; n.s., not significant (p > 0.05).

Asterisk, number indicates cases where only a fraction of individuals from a line were checked for fluorescence.

×, these experiments were stopped at the embryonic stage.

Stable transgene transmission over several generations

Further examination of the germline-integrate 3xP3::EGFP transgene activity revealed fluorescence patterns identical to the ones previously reported with piggyBac-mediated integration (Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022), consistent with glial expression in embryos, and ocelli expression in larvae (Figs. 1D, 1E, Video S1). In the depigmented eyes from the wFog strain, the retinal expression of EGFP was strong enough to reveal a green tint of the eyes, visible without fluorescent microscopy equipment (Fig. 1F).

In addition, out of the 59 G1 pupae with eye fluorescence generated from Experiment #1, 10 showed an additional, unexpected fluorescence in pupal oenocytes (Stendell, 1912; Shirk & Zimowska, 1997; Makki, Cinnamon & Gould, 2014), visible as ventral metameric belts in the second to seventh abdominal segments (Fig. 1C’, Fig. S2). This activity is likely due to an identical insertion shared between these 11 siblings. Below we refer to this randomly captured oenocyte activity as coming from a single EGFP+/oeno allele, and dub the transgene alleles that lack it EGFP+. To further test the transmissibility of these G1 insertion alleles, we generated four crosses each consisting of a single EGFP+ or EGFP+/oeno G1 founder mixed with four non-transgenic individuals from the opposite sex. These crosses generated 60.2% transgenic G2 offspring individuals on average (Table 2), including transmission of the EGFP+/oeno allele in the two corresponding crosses.

We then continued these experiments over the G3 and G4 generations to further assess transgene stability (Table 2). To obtain G3 offspring, we performed two backcrosses each consisting of one positive G2 female mixed with four non-transgenic white-eyed males, yielding 51.3% [EGFP+] G3 pupae in the first cross, and 46.0% [EGFP+/oeno] pupae in the second cross, each consistent with their donor parent carrying a single copy of a EGFP+ or EGFP+/oeno insertion allele (Chi-square test p > 0.7; no significant deviation from 50% transmission). Pooled in-crossing of positive G3 individuals yielded 100% G4 positive progeny in both cases, with [EGFP+] or [EGFP+/oeno] fluorescent expression patterns consistent with their G2 donor grand-parent. The persistence of ectopic oenocyte activity across four generations suggests that the location of the expression cassette was stable and had not been subjected to re-transposition.

The FibL promoter enables fluorescent marking of the silk glands

Next, to provide an alternative marker to eye/glia in future experiments, we designed a new donor plasmid aimed at labeling the silk glands. In Bombyx, the promoter of the Fibroin-L silk gene (FibL) drives fluorescent protein expression in the posterior region of the silk glands, enabling detection through the cuticle. This promoter has notably been used as a transgenesis marker in experiments where the labeling of neural tissues is unwanted (Imamura et al., 2003; Fujiwara et al., 2014). To implement a similar strategy, we cloned a 1 kb fragment of the Plodia FibL proximal promoter to drive the expression of mBaoJin—a recently developed monomeric fluorophore with remarkable brightness and photostability (Zhang et al., 2024) followed by a P10 3′UTR sequence (Xu et al., 2022). This cassette was cloned upstream of a 3xP3::mCherry red fluorescence eye marker in order to monitor successful integrations.

Injections of the resulting Minos donor plasmids yielded positive hatchling larvae and pupae expressing distinguishable mosaic patches of 3xP3::mCherry expression in the eye/glia (Figs. 2A, 2B). We conducted two independent injections trials using this plasmid, Experiments #4 and #5. Experiments #4 generated only one somatic transformant out of 77 pupae (Table 1), and random in-crossing of this large pool of founders successfully generated transgenic 22 transgenic G1 larvae, out of more than a hundred screened larvae (we failed to record an exact number of screened larvae, and can not provide a germline transmission rate in this experiment). These G1 individuals successfully transmitted transgenes into G2 backcrosses in a pattern consistent with the segregation of single-copies (Table 3). In Experiment #5, five out of 32 G0 pupae showed mosaic 3xP3::mCherry expression (Table 1), but these somatic transformants failed to pass a transgene into a G1 generation, confirming that somatic mosaicism in the pupal eyes is a poor indicator of germline transformation. In contrast, a pooled in-cross of the 17 remaining negative G0 individuals yielded a high-rate of germline transmission, with 51 out 518 embryos showing strong 3xP3 activity (Fig. 2C, Table 3).

| Experiment | Gen. | Cross design | Embryos | Larvae | Chi-2: 50% ratio, single insert |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | mCher+ | Total | mCher+ | mBaoJ+ | ||||

|

pMi[3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaoJin] Experiment #4 |

G1 | Random in-cross of 77 G0 founders: 1 mCherry+, 76 mCherry−, sexes n.d. | – | – | n.d. (>100) | 22 | 22 | n.a |

| G2 | 4 wFog ☿ × 1 G1 [mCherry+] ♂ | – | – | 0 | – | – | ||

| 4 wFog ☿ × 1 G1 [mCherry+] ♂ | – | – | 145 | 69 (47.5%) | 69 (47.5%) | n.s. | ||

| 1 G1 [mCherry+] ☿ × 4 wFog ♂ | – | – | 242 | 114 (47.1%) | 114 (47.1%) | n.s. | ||

| 1 G1 [mCherry +] ☿ × 4 wFog ♂ | – | – | 195 | 94 (48.2%) | 94 (48.2%) | n.s. | ||

| 6 G1 [mCherry+] ☿ × 8 G1 [mCherry+] ♂ | 74* | 65 (87.8%) | 65 (87.8%) | n.a | ||||

|

pMi[3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaoJin] Experiment #5 |

G1 | Random in-cross of 27 G0 founders: 13 [mCherry−] ☿ × 14 [mCherry−] ♂ | 518 | 51 (9.8%) | × | – | – | n.a |

| 4 wFog ☿ × 1 [mCherry+] ♂ | 168 | 0 (0%) | – | – | – | – | ||

| 4 [mCherry+] ☿ × 7 wFog ♂ | 160 | 0 (0%) | – | – | – | – | ||

Notes:

The last column indicates the p-value of Chi-square tests of difference to a 50% distribution. Results are in bold for back-crosses to wFog, where a 50% segregation is expected from a single-insertion in the transgenic donors.

Gen., generation; mCher+, mCherry-positive; mBaoJ+, mBaoJin-positive; n.a., not applicable (a 50% distribution is not expected in these crosses); n.d., not determined; n.s., not significant (p > 0.05).

Asterisk, number indicates cases where only a fraction of individuals from a line were checked for fluorescence.

×, these experiments were stopped at the embryonic stage.

In G1 larvae, we detected FibL::mBaojin activity in sections of two inner tubes on either side of the gut, spanning the A3-A6 segments, directly screenable through the cuticle (Figs. 2C, 2D, Videos S2). Dissected glands show that FibL::mBaoJin fluorescence is confined to the Posterior Silk Gland (PSG, Figs. 2F, 2F’). This compartment of the silk gland is specialized in the expression of the fibroin genes FibL and FibH (Figs. 2F, 2F’), and is thus consistent with the FibL promoter recapitulating its endogenous expression in Plodia (Alqassar et al., 2025). Notably, in G1 larvae, FibL expression in the PSG was also visible when screening with an RFP filter (Video S3), suggesting that the FibL promoter may be interacting with mCherry in addition to mBaojin, which could be due to the absence of insulator sequences between the two expression cassettes. G1 donor successfully established G2 lines in controlled crosses, including in four backcrosses where segregation ratios indicate that a single-insertion allele is present. Even in these G2 individuals carrying a single-copy of the transgene, fluorescence of both the mCherry and FibL markers provided extremely bright signals that enable fast screening (Videos S4, S5).

Overall, these data further confirm the efficiency of Minos transgenesis for a second donor plasmid, and the FibL::mBaoJin cassette provides a marker that is easily screenable in Plodia throughout the entire larval stage (Fig. 3A). The FibL promoter could be used in the future to drive the expression of other fluorescent markers or ectopic silk factors in the Plodia Posterior Silk Gland.

Figure 3: Minos transgenesis tools and procedure for the isolation of single-copy G1 transgenic founders.

(A) Plasmids used in this study. (B) Suggested procedure for isolating single-copy transgenicheterozygotes at the G1 generation, using reciprocal back-cross pools of G0 and uninjected males and females. Alternatively, the G0 injected stock can be randomly in-crossed if multiple transgene copies are acceptable or preferable, as performed in this study (Tables 2, 3). Chronology is indicated in days for a 28 °C rearing temperature. Full rearing procedures are available online (Heryanto et al., 2025).Discussion

Recommendations for successful transgenesis in Plodia and beyond

The feasibility of transgenesis experiments depends not only on the germline integration rate of the transposase system, but also on other logistic criteria such as the injection, rearing and crossing efforts. Below, we elaborate on these aspects and provide experimental considerations with the overarching goal to facilitate implementation in Plodia and other lepidopteran organisms.

We detected lower rates of G0 mosaic fluorescence with Minos compared to previous HyPBase experiments, with 9.0% of the G0 injected eggs and 9.6% of surviving pupae showing a 3xP3-driven signal, compared to 22% of injected eggs and 32% of surviving pupae with HyPBase (Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022). However, here we established that G0 injectees devoid of visible somatic activity are effective germline carriers of the transgene. As a consequence, we propose that the random in-crossing of these negative G0 injectees, performed in pools of adults, offers a practical route to the generation of transgenic lines. For example, in Experiment #1, 341 embryos were microinjected (an effort of only 3 h for two experimenters). In order to establish a G1 line, all 14 surviving adults from the injected batch were transferred to a larval diet container and allowed to randomly mate. This approach generated a large proportion of G1 individuals with 3xP3-driven fluorescence, with 23.6% of 250 screened pupae showing EGFP expression in their eyes, which were then used to establish two transgenic lines (EGFP+ and EGFP+/oeno). In other words, we recommend in-crossing all G0 individuals to ensure germline transmission and the generation of G1 transformants. Indeed, crossing of small numbers of G0 individuals can be time-consuming or yield unsuccessful matings, and selecting G0 somatic transformants as founders entails the risk that the transgene has not been integrated into the germline. This approach is supported by our results from in-crossing all phenotypically G0 negative individuals across several experiments, which all resulted in large G1 cohorts with >10% transgenic individuals to select from to establish stable lines (Tables 2, 3). In contrast, backcrosses of positive G0 individuals was successful in Experiment #2, but failed to produce any G1 transformants in Experiment #5.

The pooled G0 crossing scheme presents some caveats. First, not being able to trace how many individuals reproduced, we could not accurately measure germline integration rates as previously done in other insects, including our report of successful transgenesis in Plodia using the Hyperactive piggyBac transposase (Gregory et al., 2016; Heryanto, Mazo-Vargas & Martin, 2022). With the current data, it is unclear which of the Minos or Hyperactive piggyBac transposases drives the highest rates of germline transformation. Second, pooling G0 siblings risks creating G1 individuals inheriting several insertion sites. While having several insertions segregating in a line is not always an issue, e.g., if a transgene is designed to fluorescently label structures for qualitative imaging, or for testing the ability of select promoters to drive tissue specific expression (e.g., the FibL promoter), this could be a concern for quantitative or expression-reporter assays that may be influenced by positional effects. In such cases, we recommend sorting G0 pupae by sex (Heryanto et al., 2025), and mix a pool of G0 males to an equivalent number of uninjected females, and vice-versa (Fig. 3B). Generating a synchronized stock can facilitate this, simply by leaving a portion of the collected embryos uninjected at the beginning of the experiment.

Alternatively, if G1 broods originate from an in-cross of pooled G0 siblings, mixing single G1 transgenic individuals with non-transgenic individuals should generate a majority of G2 lines where a single transgene insert is segregating. It is worth noting that while we observed 50% segregation ratios consistent with single-inserts among our G2-to-G4 generations (Tables 2 and 3), we have not determined whether these lines include transcriptionally silent transgene copies, which might exist if Minos-mediated insertions can occur in heterochromatin regions. Inverse/splinkerette polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or sequencing techniques could be used in the future to map the position of inserts in the genome (Potter & Luo, 2010; Pavlopoulos, 2011; Stern, 2016).

Flexible marker choice using 3xP3 and FibL drivers and various fluorophores

The 3xP3:EGFP and 3xP3:mCherry markers provide a reliable labeling on larval ocelli, glial tissue, and eyes across insects, including the hemimetabolous crickets and firebrats (Gonzalez-Sqalli, Caron & Loppin, 2024; Inada, Ohde & Daimon, 2025). This signal was strong enough to be screened throughout the cuticle throughout the entire larval stage of the Plodia wFog strain, in which a white gene null mutation not only results in white eyes but also in increase translucency of the larval cuticle (Heryanto et al., 2022). In species where opaque cuticle may block fluorescence, or where a white-eyed mutant line is not available, it is still be possible to screen for 3xP3 activity in the larval lateral ocelli (Thomas et al., 2002), or in early pupal eyes before melanization occurs (Özsu et al., 2017).

This said, these features make the 3xP3 constraining to use, and we expect FibL-driven fluorescence to provide an interesting alternative in some species, particularly those with a reasonably translucent or clear cuticle in the first larval instars. And not only FibL may be more convenient to screen, it may also be preferred for experimental reasons, particularly in neurogenetics studies where tagging neural tissues may be undesirable (Fujiwara et al., 2014).

Last, we tested mBaoJin for the first time in a lepidopteran insect, as a monomeric version of the StayGold fluorophores, which show improved photostability and brightness over existing green fluorescent proteins (Zhang et al., 2024). Its successful tagging of the silk gland makes it a promising tool as a fusion-protein or expression reporter for Lepidoptera in-vivo studies. A plasmid carrying Minos repeats, 3xP3:mCherry, and the Plodia-derived FibL:mBaoJin marker is available on the Addgene repository for academic use (Addgene #240410).

Conclusions

Our data, together with a previous report in Bombyx (Uchino et al., 2007), show that Minos transgenesis is applicable to lepidopteran systems, provided it is possible to inject early syncytial embryos and maintain relatively inbred lines. Given the risks of transgene remobilization and instability associated with piggyBac transposases of lepidopteran origin, we urge researchers interested in developing transgenesis in moths or butterflies to consider using Minos-based tools.

Supplemental Information

Control autofluorescence and fluorescent screening examples.

(A) Autofluorescence of an uninjected control egg (left), larva (middle), and pupa (right), imaged separately under the GFP and RFP filter sets. (B) Examples of G2 embryos positive for 3xP3::EGFP activity in different orientations (from Experiment #1). (C) G2 embryos and hatchlings positive (arrowheads) and negative (asterisks) for 3xP3::EGFP activity (from Experiment #1). (D) Side by side comparison of G0 positive mosaics for 3xP3::EGFP (arrowheads) with their negative siblings, separated by sex. (E) G1 positive (arrowheads) and negative embryos for 3xP3::mCherry (from in-cross of G0 negatives from Experiment #5). Arrowheads (B-E): bright cellular expression of transgene markers not observed in controls

A stable transgenic line with ectopic oenocyte expression of pMi[3xP3::EGFP] in a portion of G1 progeny.

(A) 10 out of 59 (17%, Experiment #1) G1 pupae positive for 3xP3::EGFP showed fluorescent activity in metameric belts of cells restricted to the abdominal segments A2 to A7 (white arrowheads). This oenocyte-marking activity, likely derived from a specific insertion site, has been maintained over 3 subsequent generations (G2–G4), attesting to the stability of this EGFP+/oeno insertion allele without remobilization. (B) Dissection of the pupal cuticle with internal tissues and fat body partially removed. Fluorescence is detected in large cells embedded under the cuticle and in proximity to tracheal projections. These cells have been described as oenocytes in the closely related phycitine moth Ephestia kuehniella (Stendell, 1912). Abbreviations: tr, trachea ; fb, fat body; oe, oenocytes.

Control experiments assessing the effect of mock injections on egg hatching rates.

Mock injections consisted of injections conditions identical to the transgenesis Experiments #1 to #3, minus the presence of transposase mRNA.

Fluorescent detection of the 3xP3::EGFP transgene in G2 hatchlings.

pMi[3xP3::EGFP] fluorescence activity in G2 first-instar larvae shortly before (left) and during hatching (right), imaged using an EGFP filter set. Shown at real-time speed.

Fluorescent detection of the FibL::mBaojin marker in a transgenic G1 hatchling.

FibL::mBaojin expression in a pMi[3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaojin] G1 fifth-instar larva, imaged using an EYFP filter set. Shown at real-time speed.

Fluorescent detection of the 3xP3::mCherry marker in a transgenic G1 fifth instar larva.

3xP3::mCherry expression in a pMi[3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaojin] G1 fifth-instar larva, imaged using an RFP filter set. Bright expression of 3xP3::mCherry is detected in the central brain, ocelli, and in isolated ganglia along the body length. Visible expression in the silk glands is likely due to cross-over activity of the FibL promoter. Shown at real-time speed.

Fluorescent detection of the FibL::mBaojin and 3xP3::mCherry markers in transgenic G2 larvae.

FibL::mBaojin (blue/green, GFP filter set) and 3xP3::mCherry (red, RFP filter set) are shown consecutively at normal speed, followed by a zoom in the RFP channel at 0.3X speed highlighting the expression of mCherry in the larval heads and ocelli.

Fluorescent detection of the FibL::mBaojin marker in transgenic G2 larvae.

FibL::mBaojin (blue/green, GFP filter set) is shown at normal speed across a few larvae to highlight its bright fluorescence and ease of screening.

![Tissue-specific activities of the [3xP3::mCherry, FibL::mBaojin] transgene following Minos -mediated integration.](https://dfzljdn9uc3pi.cloudfront.net/2025/20249/1/fig-2-1x.jpg)