The critical relationship between vaginal microecology and Ureaplasma urealyticum: a retrospective study

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Konstantinos Kormas

- Subject Areas

- Gynecology and Obstetrics, Women’s Health

- Keywords

- Ureaplasma urealyticum, Vaginal microecology, Infection, Association

- Copyright

- © 2026 Liu et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. The critical relationship between vaginal microecology and Ureaplasma urealyticum: a retrospective study. PeerJ 14:e19783 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.19783

Abstract

Background

Vaginal microecology can reveal the health of the female reproductive tract directly. Female vaginal microecology reflects the state of female reproductive tract health. This study aimed to utilize a variety of female vaginal microecological indicators to comprehensively assess the relationship between the level of vaginal microecological health and Ureaplasma urealyticum (UU) infection in women.

Methods

A total of 408 participants were included in this study, including 144 UU-positive and 264 UU-negative individuals. Clinical information of the participants was collected, and vaginal microecological indicators (cleanliness, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), leukocyte esterase (LEU), sialidase (SNA), N-acetyl glucosidase (NAG), and β-glucuronidase (GUS)) were tested. The measurement data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s), and the comparison of data between groups was performed using a t-test; count data were expressed as the number of cases (percentage) (n[%]), and the data between groups were compared using the chi-square test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model analyses explored the factors modifying infection with UU.

Results

UU-positive patients exhibited higher rates of cleanliness positivity, H2O2 positivity, LEU positivity, SNA positivity, NAG positivity, and GUS compared to UU negative patients (P < 0.05) . The univariate logistic regression model found that cleanliness, H2O2, LEU, SNA, NAG, and GUS were risk factors for UU infection in women (Cleanliness: odds ratio [OR] = 4.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] [2.79–6.63]); H2O2: OR = 9.01, 95% CI [5.33–15.23]; LEU: OR = 1.88, 95% CI [1.22–2.91]; s SNA: OR = 5.53, 95% CI [2.73–11.19]; NAG: OR = 2.41, 95% CI [1.35–4.30]; and GUS: OR = 1.95, 95% CI [1.21–3.15]) . The multivariate logistic regression model found that the independent risk factors for UU infection in patients were cleanliness (OR = 3.00, 95% CI [1.66–5.43]) and H2O2 (OR = 7.24, 95% CI [4.19–12.51]).

Conclusions

Vaginal cleanliness and H2O2 abnormalities are risk factors for UU infections in women. Therefore, female UU infections can be prevented by maintaining vaginal microecology.

Introduction

Ureaplasma urealyticum (UU) is a bacterium included in the genus Ureaplasma. UU is a commonly found microorganism in the human reproductive tract and is generally associated with reproductive tract infections. Infection with UU manifests itself clinically as an extensive range of symptoms, particularly in women, and may lead to diseases such as vaginitis and pelvic inflammatory disease (Bender & Gundogdu, 2022; Liu et al., 2023). The proportion of UU infections varies in the bacterial vaginosis (BV) and aerobic vaginitis (AV) groups compared to healthy women (Rumyantseva et al., 2018). Thus, vaginal dysbiosis and different flora status reflect different vaginosis in women (Abou Chacra, Fenollar & Diop, 2022). Detection of interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) levels in vaginal specimens from pregnant women in early pregnancy has been associated with UU infection (Doh et al., 2004). However, UU positivity in the female vagina is not associated with abnormal vaginal secretions or pH (Plummer et al., 2021). The female vaginal microecology is a complex and dynamic microecosystem composed of vaginal microorganisms, the endocrine system, and the local immune system, and normal vaginal microbiota is essential for maintaining microecosystem homeostasis. Therefore, the relationship between patients with UU infections and vaginal microecological health status remains to be determined. In the future, to prevent and treat vaginal diseases more effectively, it will be necessary to explore and the impact of UU on the microecology of the female vagina.

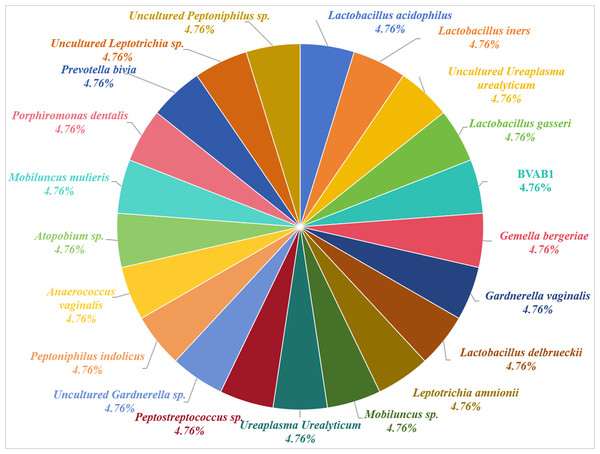

The female vagina is a complex microbial ecosystem. The female reproductive tract’s microbiome reflects the woman’s health, and a healthy microbiome consists mainly of Lactobacillus (Moreno & Simon, 2018). Hernández-Rodríguez et al. (2011) tested vaginal secretions from healthy pregnant women and identified 21 different microorganisms, with the highest positive detection rate of 21% for the UU, which is associated with bacterial vaginosis (Fig. 1). The women’s vaginal microecology changes continuously before, during, and after childbirth during puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause (Shen et al., 2022). Human vaginal microecology imbalances can lead to inappropriate inflammatory responses and abnormal immune responses, leading to a wide range of female reproductive health challenges (Shen et al., 2022). The levels of vaginal hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are associated with the presence of a wide range of microorganisms (Hillier et al., 1993). Several studies have indicated that six indicators such as pH, H2O2, leukocyte esterase (LEU), sialidase (SNA), β-glucuronidase (GUS), and acetylglucosidase assist in understanding vaginal microecology and diagnosing vaginitis and cervical cancer (Feng et al., 2024; Li et al., 2020). Additionally, Wang, Wan & Zhang (2024) found that Systemic Immune Inflammation Index (SII) is associated with Mycoplasma pneumonia, and can be used as a valid indicator for predicting its severity in children. Patients with UU infection are associated with abnormalities in inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin-6, and toll-like receptor 2 (Jacobsson et al., 2009; Hassanein et al., 2012; Noh et al., 2019). Therefore, vaginal microecology may assist in better understanding, studying, and treating UU. Studies have indicated that vaginal microecology may be associated with human papillomavirus, vaginitis, and other female reproductive tract disease infections (Ilhan et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2024; Wei et al., 2022). Always although both vaginal microecology and UU positivity are associated with female diseases, the relationship between them has not been clarified.

Figure 1: Microorganisms in the vagina of women.

The monitoring of vaginal microecology-related and inflammation indicators can assist in the diagnosis and adjuvant treatment of vagina-related diseases in women. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the association between vaginal microecological factors and UU infection to provide new ideas for further research and clinical treatment of UU.

Materials & Methods

General information

Female participants who attended the outpatient clinic of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Tangshan Workers Hospital and Tangshan Fengnan District Hospital from June 2021 to June 2024 were included in this retrospective study. Participants who had received antibiotic treatment in the last month, those with other vaginal pathogenic bacteria infections, and those with missing samples or insufficient sample size were excluded. A total of 408 study participants were finally included, including 144 UU-positive and 264 UU-negative individuals. The study was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Tangshan Fengnan District Hospital (approval number: 2022-05). Each participants provided written informed consent after receiving a detailed explanation of the study purposes and study procedures.

Sample collection

A doctor collected vaginal samples for UU testing (Feng et al., 2024). At the time of the speculum examination of the study subjects, the physician used two sterile disposable swabs to collect vaginal secretions from the subject’s posterior vaginal fornix. One sample was stored in a refrigerator at 2–4 °C and had to be completed on the day of sampling for vaginal microbiology and vaginal cleanliness testing. The other sample was stored at −80 °C for UU testing.

Approximately three mL of peripheral blood of the participants was collected to detect SII.

Sample testing

This study used real-time fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect UU in the samples. Ureaplasma urealyticum Fluorescent Polymerase Chain Reaction Diagnostic Kit (Daan Gene Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) was used in this study. Concentrations of U. urealyticum DNA ≥500 copies/ml were considered positive (Yoshida et al., 2022).

The vaginal microecological balance of the participants was observed by the Vaginitis Diagnostic kit (Zhuhai Lituo Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Zhuhai China), which included H2O2 (H2O2 results were determined as H2O2 (negative) when H2O2 ≥2 µmol/L in vaginal secretions, indicating normal microbial function in the vagina; otherwise, the results were positive), LEU, SNA, N-acetyl glucosidase (NAG), GUS (Feng et al., 2024).

Vaginal cleanliness (Zheng et al., 2019a; Zheng et al., 2019b): Vaginal discharge was observed microscopically and vaginal cleanliness was categorized as I. to IV based on the number of bacilli, epithelial cells and white blood cells (WBC). Grade I–II indicates normal vaginal cleanliness, and grade III–IV indicates abnormal vaginal cleanliness. Grade I is the presence of a large number of Lactobacillus vaginalis, epithelial cells, and no other bacteria in the vaginal discharge observed under the microscope, with a white blood cell count of 0–5/HP. Grade II is the presence of some Lactobacillus and vaginal epithelial cells, some pus cells, and other bacteria observed microscopically in vaginal discharge with a WBC of 10–15/HP. Grade III is the presence of a few Lactobacillus, pus cells, and other bacteria observed microscopically with a WBC of 15–30/HP. Grade IV is the presence of no Lactobacillus but pus cells and other bacteria observed microscopically with a WBC of more than 30/HP. Grade V is the absence of Lactobacillus, but pus cells and other bacteria were observed microscopically with a WBC of more than 30/HP.

Neutrophil, lymphocyte, and platelet counts were measured using a BC-3200 automatic blood cell analyzer. SII was calculated, SII = (platelet count × neutrophils count)/lymphocytes count.

Statistical analysis

The data of participants were analyzed using SPSS23.0 software. Among them, the measurement data were expressed as mean ±standard deviation (x ±s). Moreover, the t-test was used for the data between groups; the count data were expressed as cases (percentage) (n [%]), and the chi-square test was used. The factors influencing infection with UU were explored through univariate and multivariate logistic regression model analyses. The test level was set at α = 0.05, and differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Study population

A total of 408 female participants, including 144 UU-positive and 264 UU-negative, were included. As illustrated in Table 1, the percentage of UU-positive participants with high vaginal cleanliness (34.03%) was lower than the UU-negative population (68.94%, P < 0.05); the percentage of UU-positive participants with vaginal H2O2 positivity (85.42%) was higher than the UU-negative population (39.39%, P < 0.05); the percentage of UU-positive participants with LEU-positive participants (71.53%) accounted for a higher proportion than the UU-negative population (57.20%, P < 0.05); SNA-positive participants (20.83%) accounted for a higher proportion of UU-positive participants than the UU-negative population (4.55%, P < 0.05); NAG-positive participants (20.14%) was higher than the UU-negative population (9.47%, P < 0.05); and the percentage of UU-positive participants with GUS positivity (29.17%) was higher than the UU-negative population (17.42%, P < 0.05). The comparison of data in the age, age of menarche, number of pregnancies, number of miscarriages, and SII groups between the two groups of participants demonstrated no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05).

| Characteristics | All (n = 408) |

UU-Negative (n = 264) |

UU-Positive (n = 144) |

x2/t | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 36.48 ± 11.55 | 36.11 ± 12.07 | 37.15 ± 10.56 | −0.87 | 0.383 | |

| Age of menarche (year) | 13.51 ± 1.11 | 13.51 ± 1.04 | 13.52 ± 1.23 | −0.08 | 0.938 | |

| Number of pregnancies | <=1 | 104 (25.49) | 65 (24.62) | 39 (27.08) | 0.30 | 0.586 |

| >1 | 304 (74.51) | 199 (75.38) | 105 (72.92) | |||

| Number of miscarriages | <=1 | 171 (41.91) | 108 (40.91) | 63 (43.75) | 0.31 | 0.578 |

| >1 | 237 (58.09) | 156 (59.09) | 81 (56.25) | |||

| SII | Low | 204 (50.00) | 136 (51.52) | 68 (47.22) | 0.69 | 0.407 |

| High | 204 (50.00) | 128 (48.48) | 76 (52.78) | |||

| cleanliness | I or II | 231 (56.62) | 182 (68.94) | 49 (34.03) | 46.24 | <0.001 |

| III or IV | 177 (43.38) | 82 (31.06) | 95 (65.97) | |||

| H2O2 | Negative | 181 (44.36) | 160 (60.61) | 21 (14.58) | 79.96 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 227 (55.64) | 104 (39.39) | 123 (85.42) | |||

| LEU | Negative | 154 (37.75) | 113 (42.80) | 41 (28.47) | 8.14 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 254 (62.25) | 151 (57.20) | 103 (71.53) | |||

| SNA | Negative | 366 (89.71) | 252 (95.45) | 114 (79.17) | 26.77 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 42 (10.29) | 12 (4.55) | 30 (20.83) | |||

| NAG | Negative | 354 (86.76) | 239 (90.53) | 115 (79.86) | 9.24 | 0.002 |

| Positive | 54 (13.24) | 25 (9.47) | 29 (20.14) | |||

| GUS | Negative | 320 (78.43) | 218 (82.58) | 102 (70.83) | 7.59 | 0.006 |

| Positive | 88 (21.57) | 46 (17.42) | 42 (29.17) | |||

Notes:

- H2O2

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- LEU

-

Leukocyte esterase

- SNA

-

sialidase

- NAG

-

N-acetyl glucosidase

- GUS

-

β-glucuronidase

- P-value

-

probability value

Univariate logistic analysis of the association between vaginal microecology and UU

Univariate logistic regression analyses of participants basic clinical information, SII, and vaginal microecology were conducted to find risk factors for UU infection in women. As shown in Table 2, participants with low cleanliness (III or IV) had a significantly higher risk of UU infection than that in those with high cleanliness (I or II) (odds ratio [OR ] = 4.30, 95% confidence interval [CI ] [2.79–6.63], P < 0.001); H2O2-positive participants had a significantly higher risk of UU infection compared to H2O2-negative participants (OR = 9.01, 95% CI [5.33–15.23], P < 0.001); LEU-positive participants had a significantly higher risk of UU infection compared to LEU-negative participants (OR = 1.88, 95% CI [1.22–2.91], P < 0.001); SNA-positive participants had a significantly higher risk of UU infection compared to SNA-negative participants (OR = 5.53, 95% CI [2.73–11.19], P < 0.001); NAG-positive participants had a significantly higher risk of UU infection than NAG-negative participants (OR = 2.41, 95% CI [1.35 to −4.30], P = 0.003); GUS-positive participants had a significantly higher risk of UU infection than GUS-negative participants (OR = 1.95, 95% CI [1.21–3.15], P = 0.006). However, no significant association was observed between age, age of menarche, number of pregnancies, number of miscarriages, and SII and infection with UU in women (P > 0.05).

| Characteristics | All (n = 408) |

UU-Negative (n = 264) |

UU-Positive (n = 144) |

OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 36.48 ± 11.55 | 36.11 ± 12.07 | 37.15 ± 10.56 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.382 | |

| Age of menarche (year) | 13.51 ± 1.11 | 13.51 ± 1.04 | 13.52 ± 1.23 | 1.01 (0.84–1.21) | 0.934 | |

| Number of pregnancies | <=1 | 104 (25.49) | 65 (24.62) | 39 (27.08) | Reference | Reference |

| >1 | 304 (74.51) | 199 (75.38) | 105 (72.92) | 0.88 (0.55–1.40) | 0.586 | |

| Number of miscarriages | <=1 | 171 (41.91) | 108 (40.91) | 63 (43.75) | Reference | Reference |

| >1 | 237 (58.09) | 156 (59.09) | 81 (56.25) | 0.89 (0.59–1.34) | 0.578 | |

| SII | Low | 204 (50.00) | 136 (51.52) | 68 (47.22) | Reference | Reference |

| High | 204 (50.00) | 128 (48.48) | 76 (52.78) | 1.19 (0.79–1.78) | 0.407 | |

| cleanliness | I or II | 231 (56.62) | 182 (68.94) | 49 (34.03) | Reference | Reference |

| III or IV | 177 (43.38) | 82 (31.06) | 95 (65.97) | 4.30 (2.79–6.63) | <0.001 | |

| H2O2 | Negative | 181 (44.36) | 160 (60.61) | 21 (14.58) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 227 (55.64) | 104 (39.39) | 123 (85.42) | 9.01 (5.33–15.23) | <0.001 | |

| LEU | Negative | 154 (37.75) | 113 (42.80) | 41 (28.47) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 254 (62.25) | 151 (57.20) | 103 (71.53) | 1.88 (1.22–2.91) | <0.001 | |

| SNA | Negative | 366 (89.71) | 252 (95.45) | 114 (79.17) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 42 (10.29) | 12 (4.55) | 30 (20.83) | 5.53 (2.73–11.19) | <0.001 | |

| NAG | Negative | 354 (86.76) | 239 (90.53) | 115 (79.86) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 54 (13.24) | 25 (9.47) | 29 (20.14) | 2.41 (1.35–4.30) | 0.003 | |

| GUS | Negative | 320 (78.43) | 218 (82.58) | 102 (70.83) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 88 (21.57) | 46 (17.42) | 42 (29.17) | 1.95 (1.21–3.15) | 0.006 | |

Notes:

- H2O2

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- LEU

-

Leukocyte esterase

- SNA

-

sialidase

- NAG

-

N-acetyl glucosidase

- GUS

-

β-glucuronidase

- P-value

-

probability value

- CI

-

confidence interval

- OR

-

odds ratio

Multivariate logistic analysis of the association between vaginal microecology and UU

To explore the independent risk factors for UU infection risk, statistically significant variables (P < 0.05) in the univariate logistic regression analysis in the subsequent multivariate logistic regression analyses were included (Table 3). The endpoint dependent variable was whether the patient was infected with UU (negative = 0, positive = 1) and multivariate logistic analysis was performed with cleanliness (negative = 0, positive = 1), H2O2 (negative = 0, positive = 1), LEU (negative = 0, positive = 1), SNA (negative = 0, positive = 1), NAG (negative = 0, positive = 1), and GUS (negative = 0, positive = 1) as independent variables for multivariate logistic analysis. Cleanliness (OR = 3.00, 95% CI [1.66–5.43], P < 0.001) and H2O2 (OR = 7.24, 95% CI [4.19–12.51], P < 0.001) were independent risk factors for UU infection in participants. However, the remaining vaginal microecological factors (LEU, SNA, NAG, GUS) have not shown an independent risk of UU infection (P > 0.05).

| Characteristics | All (n = 408) |

UU-Negative (n = 264) |

UU-Positive (n = 144) |

OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cleanliness | I or II | 231 (56.62) | 182 (68.94) | 49 (34.03) | Reference | Reference |

| III or IV | 177 (43.38) | 82 (31.06) | 95 (65.97) | 3.00 (1.66–5.43) | <0.001 | |

| H2O2 | Negative | 181 (44.36) | 160 (60.61) | 21 (14.58) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 227 (55.64) | 104 (39.39) | 123 (85.42) | 7.24 (4.19–12.51) | <0.001 | |

| LEU | Negative | 154 (37.75) | 113 (42.80) | 41 (28.47) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 254 (62.25) | 151 (57.20) | 103 (71.53) | 0.86 (0.48–1.53) | 0.611 | |

| SNA | Negative | 366 (89.71) | 252 (95.45) | 114 (79.17) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 42 (10.29) | 12 (4.55) | 30 (20.83) | 1.81 (0.80–4.09) | 0.156 | |

| NAG | Negative | 354 (86.76) | 239 (90.53) | 115 (79.86) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 54 (13.24) | 25 (9.47) | 29 (20.14) | 1.47 (0.75–2.86) | 0.263 | |

| GUS | Negative | 320 (78.43) | 218 (82.58) | 102 (70.83) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive | 88 (21.57) | 46 (17.42) | 42 (29.17) | 1.08 (0.60–1.97) | 0.795 | |

Notes:

- H2O2

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- LEU

-

Leukocyte esterase

- SNA

-

sialidase

- NAG

-

N-acetyl glucosidase

- GUS

-

β-glucuronidase

- P-value

-

probability value

- CI

-

confidence interval

- OR

-

odds ratio

Discussion

UU, as a common reproductive tract pathogen, has become a critical threat to women’s health (Noh et al., 2019; Cicinelli et al., 2008). The factors contributing to UU infection in women were explored. The proportion of UU-positive participants who were cleanliness-positive, H2O2-positive, LEU-positive, SNA-positive, NAG-positive, or GUS-positive populations was higher than that of UU-negative populations. Cleanliness and H2O2 were found to be risk factors for UU infection in women. Consequently, to reduce vaginal microecological abnormalities and the incidence of UU infection and other diseases in women, more education should be imparted on healthy living for women.

UUs are pathogenic microorganisms that attach to various types of cells, such as epithelial and germ cells, and primarily colonize the mucosal surfaces of the genitourinary tract in adults. UU infections not only lead to reproductive tract inflammation but also to infertility and adverse outcomes of pregnancy, such as preterm premature rupture of the membrane (Li et al., 2010). This study found that a higher percentage of UU-positive participants had lower vaginal cleanliness than the UU-negative participants. No study has directly demonstrated the association between UU and vaginal cleanliness. However, cervical cancer and bacterial vaginosis are associated with abnormal vaginal cleanliness in patients (Zhang et al., 2023; Shen et al., 2024). Differences in the degree of vaginal cleanliness lead to differences in the abundance of vaginal microbial composition. Moreover, abnormalities in vaginal microbiota can cause diseases such as vaginitis (Liao et al., 2022). Thus, the vaginal microbiome plays a critical role in women’s health. UU-positive participants had a higher percentage of vaginal H2O2 positivity compared to the UU-negative participants. Although H2O2 is produced by probiotics such as lactobacilli, it can be used to assess vaginal health status, and abnormally normal levels of H2O2 may be associated with immune cytokines in vaginal secretions (Jacobsson et al., 2009; Hassanein et al., 2012; Noh et al., 2019; Mei & Li, 2022; Cai et al., 2022). Vaginal microecology, a complex system, is mediated by multiple factors, including normal anatomy, microflora, endocrine changes, and local immune responses (Ye & Qi, 2023). This is in accordance with the findings of our study that found a higher percentage of UU-positive participants with positive vaginal LEU, SNA, NAG, and GUS. Autoimmune status and viral infections were significantly associated with vaginal microbiota involved in the regulation of the immune system of the female lower genital tract, suggesting that the vaginal microflora dysbiosis may be a risk factor affecting persistent infections in the female genital tract (Pino et al., 2021). Therefore, vaginal cleanliness must be maintained, and vaginal microecology must be stable for women’s health.

An interdependence and mutual constraint exist between vaginal microecological-related factors, forming a dynamic balance system (Buggio et al., 2019). An imbalance in the vaginal microecosystem can be recognized when there is an alteration in indicators such as the number, species, dominant bacteria, pathogenic microorganisms, pH, and Lactobacillus function in the vagina (Wang et al., 2022; Ge et al., 2023). The analysis was performed between vaginal microecology and UU susceptibility. This study found that cleanliness was an independent risk factor for UU infection in patients. Similar to this study’s findings, several studies have identified the association of vaginal cleanliness with female reproductive diseases, including polycystic ovary syndrome and postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction (Hong et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2022). The route of UU infection in the female genital tract is primarily through the vagina; therefore, extensive vaginal cleansing is critical. A low vaginal cleanliness grade indicates that a woman has a large number of Lactobacillus and epithelial cells in her vagina. Still, fewer leukocytes, and the vaginal microecology is in a healthy state. In a healthy female vagina, Lactobacillus produces H2O2, which protects the vagina. Garza et al.’s study found that the percentage of patients with UU infection who were positive for Lactobacillus in the vagina was lower than the percentage of Lactobacillus positivity in the healthy control population. Combined with our findings that high vaginal cleanliness is a risk factor for UU infection in patients, we hypothesize that Lactobacillus in the vagina and the Lactobacillus product, H2O2, may be essential factors in reducing UU infection in women. In the future, this study will further explore the mechanisms by which vaginal cleanliness level affects UU infection in women. In this study, H2O2 (OR = 7.24, 95% CI [4.19–12.51], P < 0.001), another indicator of vaginal microecology, was found to be an independent risk factor for UU infection in patients. Consistent with the above results, Li et al. found that abnormal levels of H2O2 could lead to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical squamous cell carcinoma (Zheng et al., 2019a; Zheng et al., 2019b). Stoyancheva found that H2O2-producing Lactobacillus has a vital role in protecting the vaginal microecological balance (Stoyancheva, Danova & Boudakov, 2006). Women who were negative for Lactobacillus vaginalis were more likely to be infected with Mycoplasma hominis, UU et al. than those who were positive for Lactobacillus in the vagina (Hillier et al., 1993). Vaginal H2O2 is mainly derived from Lactobacillus, so we hypothesized that H2O2 may be detrimental to UU infection in female patients. In the future, we will also explore the mechanism by which vaginal H2O2 reduces UU infection in women. Therefore, maintenance of vaginal microecological stability is critical to improve women’s health.

In addition, LEU, SNA, NAG, and GUS were found to be risk factors for UU infection in women in the univariate logistic analysis of this study. still, multivariate logistic analysis found that LEU, SNA, NAG, and GUS had no significant effect on UU infection in women. First, the results of univariate analysis are affected by other confounding factors, while multifactorial analysis corrects for the effects of other confounding factors, making the results more plausible. second, it is possible that whether LEU, SNA, NAG, or GUS is positive or not is indirectly related to UU infection in women. Finally, it may be that the sample size of this study is insufficient, and we will continue to collect samples for validation afterward. This study conducted a correlation analysis between SII and UU infection in women, but the results showed no significant correlation between SII and UU infection in women. However, it has been shown that there is an increase in polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) in the vagina of women with UU infection (Bender & Gundogdu, 2022). Afterward, we will test to examine further the relationship between other inflammatory markers and UU infection and analyze the role of inflammation in UU infection.

This study systematically investigated the association between vaginal microecology and UU infection. However, it has several limitations. First, the study population is primarily concentrated in northern China. Genetic differences, environmental factors, and cultural factors are all critical factors that may influence the results of the study, so in the future, we may also improve the generalizability of our findings through multicenter collaboration and cross-population comparisons for different populations to enhance the accuracy of our findings. Second, the exploration of potential mechanisms is insufficient. Vaginal cleanliness and H2O2 content are both associated with Lactobacillus in the vagina, so we hypothesized that Lactobacillus and Lactobacillus products such as H2O2 may be detrimental to UU infection in female patients. In the future, we will explore the mechanism of vaginal cleanliness and H2O2 content on UU infection in women for this speculation to further validate and improve our findings.

In conclusion, we found that UU-positive patients exhibited higher rates of cleanliness, H2O2, and other studied factors compared to UU negative patients. In addition, cleanliness and H2O2 were identified as independent risk factors for UU infection in women. Therefore, vaginal microecological examination should be strengthened in women to prevent UU infection caused by the abnormalities of the vaginal microecology.