The clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy: a scoping review

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Charles Okpala

- Subject Areas

- Evidence Based Medicine, Kinesiology, Orthopedics, Sports Injury, Sports Medicine

- Keywords

- Tendinopathy, Diagnosis, Achilles, Tendon, Tendinosis, Tendinitis

- Copyright

- © 2021 Matthews et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2021. The clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy: a scoping review. PeerJ 9:e12166 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12166

Abstract

Background

Achilles tendinopathy describes the clinical presentation of pain localised to the Achilles tendon and associated loss of function with tendon loading activities. However, clinicians display differing approaches to the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy due to inconsistency in the clinical terminology, an evolving understanding of the pathophysiology, and the lack of consensus on clinical tests which could be considered the gold standard for diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy. The primary aim of this scoping review is to provide a method for clinically diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy that aligns with the nine core health domains.

Methodology

A scoping review was conducted to synthesise available evidence on the clinical diagnosis and clinical outcome measures of Achilles tendinopathy. Extracted data included author, year of publication, participant characteristics, methods for diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy and outcome measures.

Results

A total of 159 articles were included in this scoping review. The most commonly used subjective measure was self-reported location of pain, while additional measures included pain with tendon loading activity, duration of symptoms and tendon stiffness. The most commonly identified objective clinical test for Achilles tendinopathy was tendon palpation (including pain on palpation, localised tendon thickening or localised swelling). Further objective tests used to assess Achilles tendinopathy included tendon pain during loading activities (single-leg heel raises and hopping) and the Royal London Hospital Test and the Painful Arc Sign. The VISA-A questionnaire as the most commonly used outcome measure to monitor Achilles tendinopathy. However, psychological factors (PES, TKS and PCS) and overall quality of life (SF-12, SF-36 and EQ-5D-5L) were less frequently measured.

Conclusions

There is significant variation in the methodology and outcome measures used to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy. A method for diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy is proposed, that includes both results from the scoping review and recent recommendations for reporting results in tendinopathy.

Introduction

Achilles tendinopathy describes the clinical presentation of pain localised to the Achilles tendon and associated loss of function with tendon loading activities (De Vos et al., 2021; Millar et al., 2021). However, clinicians display differing approaches to the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy due to inconsistency in the clinical terminology, an evolving understanding of the pathophysiology, and the lack of consensus on clinical tests which could be considered the gold standard for diagnosing Achilles tendinopthy (De Vos et al., 2021; Millar et al., 2021; Docking, Ooi & Connell, 2015; Cook et al., 2016). Conversely, when describing the clinical condition of persistent pain and dysfunction of the Achilles tendon in relation to mechanical loading, consensus agreement has identified the preferred terminology to be ‘tendinopathy’ rather than other common terms such as ‘tendinitis’ and ‘tendinosis’ (Scott et al., 2020). However, the consensus agreement for terminology does not provide a clear criteria with which to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy (De Vos et al., 2021).

Additionally, when considering the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy, distinctions can be made between the diagnosis of tendinopathy and clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy. As described by Aggarwal et al. (2015), a diagnosis is based off a broad set of signs and symptoms to reflect all the potential features and severity of a pathology. Whereas, a clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy requires a specific set of signs, symptoms and tests to define a homogenous group of patients across studies and geographical regions (Aggarwal et al., 2015). In the case of Achilles tendinopathy, the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy is determined by the presentation of pain localised to the Achilles tendon and associated loss of function with tendon loading activities (De Vos et al., 2021; Millar et al., 2021). However, this broad description may include other pathological disease processes such as retrocalcaneal bursitis, complete or partial rupture of the Achilles, tarsal tunnel syndrome, neuroma/neuritis of the sural nerve, rupture posterior tibial tendon, or arthritic conditions of the ankle that need to be differentially diagnosed (Hutchison et al., 2013). Thus, it becomes relevant to understand the process to determine a clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy.

The clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy is predominantly derived from patient history, patient reported load related pain, and pain provocation tests (Millar et al., 2021). Patient history, localised Achilles tendon pain and pain on palpation are considered key to diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy (De Vos et al., 2021; Millar et al., 2021) and can all be assessed reliably (Hutchison et al., 2013). Additional pain provoking tests; such as the single leg heel raise, hop test, Royal London Hospital Test or Painful Arc Sign; have been suggested as useful to confirm a clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy (Millar et al., 2021; Hutchison et al., 2013; Reiman et al., 2014). However, many leading researchers disagree on the which clinical tests are essential to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy (De Vos et al., 2021). Conversely, it is agreed that uniform diagnostic criteria would be useful in identifying possible subclassifications of Achilles tendinopathy and thus improving tailored individual treatment programmes or monitoring patient progress (De Vos et al., 2021).

Recently, Vicenzino et al. (2020) identified nine core health domains in tendinopathy following consensus agreement from both health care practitioners and patients. These included patient rating of overall condition, pain on activity or loading, participation, function, psychological factors, disability, physical function capacity, quality of life, and pain over a specified timeframe (Vicenzino et al., 2020). An overview of the nine core health domains of tendinopathy (Vicenzino et al., 2020) are presented in Table 1. Using the determined core health domains, specific measures will need to be identified specific to Achilles tendinopathy (Vicenzino et al., 2020). The introduction of the nine core health domains in tendinopathy (Vicenzino et al., 2020) in addition to previously identified gaps in the literature, including; a lack of consistency in terminology used to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy (De Vos et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2020), lack of a consensus on the clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy (De Vos et al., 2021), and the need for a uniform method with which to clinically diagnose Achilles tendinopathy (De Vos et al., 2021). Thus there is a requirement to identify the methods with which these gaps can be addressed and allow for greater consistency in the clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy in both research and clinical practice.

| Domain | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Patient rating of overall condition | A single assessment numerical evaluation | 0–100% |

| Pain on activity or loading | Patient reported intensity of pain during a tendon loading activity. | VAS, NRS |

| Participation | Patient rating of participation levels in sport or engagement across other areas. | Tegner Activity Scale |

| Function | Patient rating of function and not referring to the intensity of their pain. | Patient Specific Function Scale |

| Psychological factors | Patient rating of psychological impact (e.g. Pain self efficacy, kinesiophobia, catastrophisation) . | PCS |

| Disability | Scores from a combination of patient rated pain and disability due to pain in relation to tendon specific loading activities | VISA-A |

| Physical function capacity | The quantitative measures of physical tasks such as number of hops, number of squats and dynamometry. | Single leg heel raise |

| Quality of life | Patient rating of general wellbeing | EQ-5D |

| Pain over a specified time | Patient reported intensity of pain over a specified time period (e.g. morning, night, 24 h). | VAS, NRS |

Note:

VAS, visual analogue scale; NRS, numerical rating scale; PCS, pain catastrophisation scale; VISA, Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 dimension.

Therefore, the primary aim of this scoping review is to provide a method for clinically diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy that aligns with the nine core health domains. In order to achieve this, specific objectives have been determined that include: (1) identifying the most common clinical tests used to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy, (2) identifying the most common outcome measures used to assess Achilles tendinopathy, and (3) summarising the studies to date.

Methodology

Study design

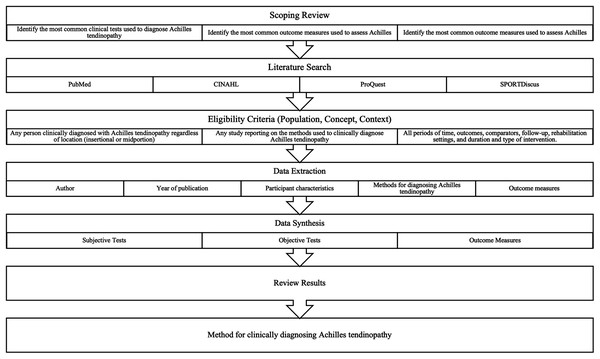

A scoping review was conducted to synthesise available evidence on the clinical diagnosis and clinical outcome measures of Achilles tendinopathy. Due to the wide-ranging nature of the topic, a scoping review was used to facilitate the collection and charting of evidence with the aim of identifying key themes, knowledge gaps and types of evidence currently available. Figure 1 provides an overview of the overall study design and process to answer the primary aim and specific objectives.

Figure 1: Overall study design.

Search strategy

A single researcher (WM) completed a literature search to identify, screen and select studies in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018). A detailed, multistep search of PubMed, CINAHL, ProQuest and SPORTDiscus was conducted between May 2020 and July 2020, before being updated in April 2021. In addition to the electronic database search, reference lists from included articles were reviewed for additional articles. To ensure a broad search, key words were truncated to allow for variations in spelling and combined using Boolean operators in addition to the use of MeSH terms to allow for review of all relevant articles. The full electronic search for the PubMed database is provided in Table 2.

| Database | Search strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“tendineous”[All Fields] OR “tendinopathy”[MeSH Terms] OR “tendinopathy”[All Fields] OR “tendinitis”[All Fields] OR “tendons”[MeSH Terms] OR “tendons”[All Fields] OR “tendinous”[All Fields] OR (“tendinopathy”[MeSH Terms] OR “tendinopathy”[All Fields] OR “tendinosis”[All Fields]) OR (“tendinopathy”[MeSH Terms] OR “tendinopathy”[All Fields] OR “tendinopathies”[All Fields]) OR (“tendinopathy”[MeSH Terms] OR “tendinopathy”[All Fields] OR “tendonopathy”[All Fields]) OR (“tendinopathy”[MeSH Terms] OR “tendinopathy”[All Fields] OR “tendonitis”[All Fields] OR “tendon s”[All Fields] OR “tendonous”[All Fields] OR “tendons”[MeSH Terms] OR “tendons”[All Fields] OR “tendon”[All Fields]) OR (“tendinopathy”[MeSH Terms] OR “tendinopathy”[All Fields] OR “tendonosis”[All Fields])) AND (“diagnosable”[All Fields] OR “diagnosi”[All Fields] OR “diagnosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “diagnose”[All Fields] OR “diagnosed”[All Fields] OR “diagnoses”[All Fields] OR “diagnosing”[All Fields] OR “diagnosis”[MeSH Subheading]) AND (“achiles”[All Fields] OR “achille”[All Fields] OR “achille s”[All Fields] OR “achilles tendon”[MeSH Terms] OR (“achilles”[All Fields] AND “tendon”[All Fields]) OR “achilles tendon”[All Fields] OR “achilles”[All Fields]) | 7,162 |

Eligibility criteria

Methods for data extraction specific to scoping reviews were informed by the Population-Concept-Context framework as recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer’s Manual (Peters et al., 2020). Population was defined as any person clinically diagnosed with Achilles tendinopathy regardless of location (insertional or midportion). Concept included any study reporting on the methods used to clinically diagnose Achilles tendinopathy including subjective measures, objective measures and outcome measures. Context included all periods of time, outcomes, comparators, follow-up, rehabilitation settings and duration and type of intervention.

Eligible articles were full-text and included original research, reviews, scoping reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, case-series and clinical commentaries. Studies were included if they provided adequate information on the method of clinical diagnosis (either subjective measures, objective measures or both subjective and objective measures), and clinical outcome measures used. Studies were excluded if they were non-English, had no description of clinical diagnosis, not specific to Achilles tendinopathy or included asymptomatic Achilles tendon states only.

Data extraction and synthesis

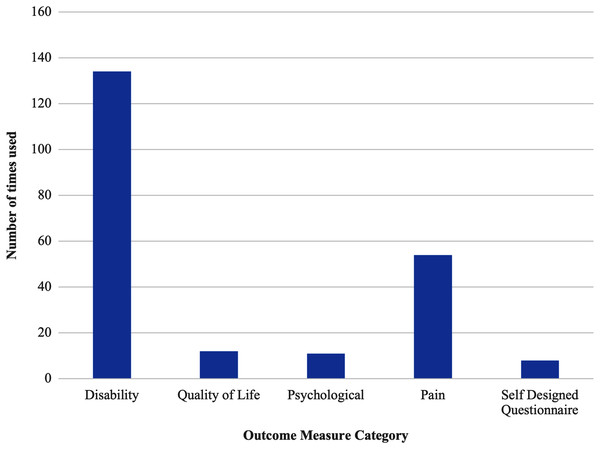

WM extracted data from publications meeting the inclusion criteria into an Excel spreadsheet. Data extraction, grouping and plotting were performed by WM in line with previously published recommendations (Peters et al., 2020), where extracted data included author, year of publication, participant characteristics, methods for diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy and outcome measures. Data was extracted in tabular and graphical forms with results grouped by study design and categorised according to the hierarchy of evidence (Daly et al., 2006; Evans, 2003; Merlin, Weston & Tooher, 2009). Diagnostic criteria were presented in tabular form including year of publication, population, subjective and objective measures. Terminology and outcome measures were presented in graphical form with terminology grouped by publication year and outcome measures grouped by purpose of measure (disability, pain, psychological, quality of life).

Following data extraction, data synthesis was performed according to a previously published methodological framework (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Data was synthesised into the following categories: (1) subjective measures, (2) objective measures and (3) outcome measures. Results were plotted according to publication date, terminology, study design and clinical diagnostic measures. Results were then compared to the nine core health domains of tendinopathy (Vicenzino et al., 2020) to identify areas of overlap and gaps in the current evidence. Studies could be allocated to multiple groups. Quality appraisal was not required as per recommended methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2020; Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

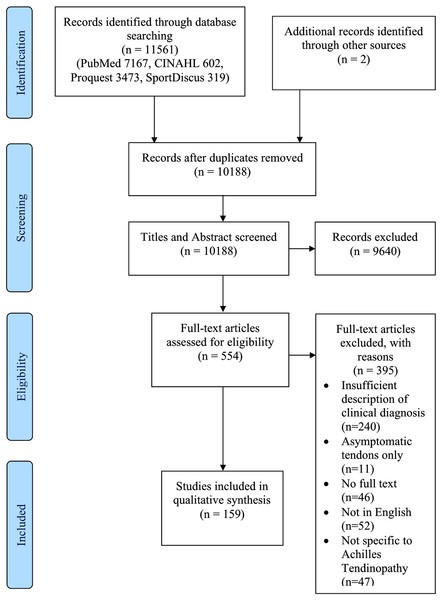

The search results are displayed in the PRISMA Flow Diagram (Fig. 2). The search strategy generated 11,561 results with two further results identified via reference list searching. Following duplicate removal and title and abstract screening, 554 full-text articles were reviewed for inclusion in the study. Of these, 395 were excluded for the following reasons: 240 provided insufficient information on the method of diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy, 11 assessed asymptomatic Achilles tendons only, 46 did not have access to the full text, 52 were not in English and 47 were not specific to Achilles tendinopathy. Thus, 159 articles (Millar et al., 2021; Hutchison et al., 2013; Reiman et al., 2014; Abate & Salini, 2019; Aiyegbusi, Tella & Sanusi, 2020; Aldridge, 2004; Alfredson, 2003; Alfredson & Cook, 2007; Alfredson & Spang, 2018; Aronow, 2005; Asplund & Best, 2013; Azevedo et al., 2009; Bains & Porter, 2006; Barge-Caballero et al., 2008; Barker-Davies et al., 2017; Baskerville et al., 2018; Benazzo, Todesca & Ceciliani, 1997; Benito, 2016; Bhatty, Khan & Zubairy, 2019; Bjordal, Lopes-Martins & Iversen, 2006; Boesen et al., 2017; Borda & Selhorst, 2017; Brown et al., 2006; Carcia et al., 2010; Cassel et al., 2018; Chazan, 1998; Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Chester et al., 2008; Chimenti et al., 2016; Chimenti et al., 2017; Chimenti et al., 2020; Cook, Khan & Purdam, 2002; Coombes et al., 2018; Courville, Coe & Hecht, 2009; Creaby et al., 2017; Crill, Berlet & Hyer, 2014; De Jonge et al., 2011; De Marchi et al., 2018; Den Hartog, 2009; Divani et al., 2010; Docking et al., 2015; Duthon et al., 2011; Ebbesen et al., 2018; Eckenrode, Kietrys & Stackhouse, 2019; Feilmeier, 2017; Finnamore et al., 2019; Florit et al., 2019; Fredericson, 1996; Furia & Rompe, 2007; Gärdin et al., 2016; Gatz et al., 2020; Habets et al., 2017; Hasani et al., 2020; Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2018; Holmes & Lin, 2006; Horn & McCollum, 2015; Hu & Flemister, 2008; Hutchison et al., 2011; Irwin, 2010; Järvinen et al., 2001; Jayaseelan, Weber & Jonely, 2019; Jewson et al., 2017; Jowett, Richmond & Bedi, 2018; Jukes, Scott & Solan, 2020; Kader et al., 2002; Karjalainen et al., 2000; Khan et al., 2003; Knobloch, 2007; Knobloch et al., 2007; Knobloch et al., 2008; Kragsnaes et al., 2014; Krogh et al., 2016; Lakshmanan & O’Doherty, 2004; Leung & Griffith, 2008; Lohrer & Nauck, 2009; Longo et al., 2009; Longo, Ronga & Maffulli, 2009; Maffulli, Giai Via & Oliva, 2015; Maffulli, Giuseppe Longo & Denaro, 2012; Maffulli & Kader, 2002; Maffulli et al., 2003; Maffulli et al., 2011; Maffulli et al., 2020; Maffulli et al., 2012; Maffulli et al., 2008; Maffulli et al., 2019; Maffulli, Sharma & Luscombe, 2004; Maffulli, Via & Oliva, 2014; Maffulli et al., 2008; Mafi, Lorentzon & Alfredson, 2001; Magnussen, Dunn & Thomson, 2009; Mansur et al., 2019; Mansur et al., 2017; Mantovani et al., 2020; Martin et al., 2018; Mayer et al., 2007; McCormack et al., 2015; McShane, Ostick & McCabe, 2007; Murawski et al., 2014; Nadeau et al., 2016; Neeter et al., 2003; Nichols, 1989; De Mesquita et al., 2018; O’Neill et al., 2019; Oloff et al., 2015; Ooi et al., 2015; Paavola et al., 2002; Paavola et al., 2002; Paavola et al., 2000; Paoloni et al., 2004; Papa, 2012; Pedowitz & Beck, 2017; Petersen, Welp & Rosenbaum, 2007; Pingel et al., 2013; Post et al., 2020; Praet et al., 2018; Rabello et al., 2020; Rasmussen et al., 2008; Reid et al., 2012; Reiter et al., 2004; Romero-Morales et al., 2019a; Rompe, Furia & Maffulli, 2009; Rompe et al., 2008; Rompe et al., 2007; Roos et al., 2004; Ryan et al., 2009; Saini et al., 2015; Santamato et al., 2019; Sayana & Maffulli, 2007; Scholes et al., 2018; Scott, Huisman & Khan, 2011; Sengkerij et al., 2009; Sharma & Maffulli, 2006; Silbernagel et al., 2007; Silbernagel et al., 2001; Simpson & Howard, 2009; Solomons et al., 2020; Sorosky et al., 2004; Stenson et al., 2018; Stergioulas et al., 2008; Syvertson et al., 2017; Tan & Chan, 2008; Thomas et al., 2010; Turner et al., 2020; Vallance et al., 2020; Van der Vlist et al., 2020; Van der Vlist et al., 2020; Van Sterkenburg et al., 2011; Verrall, Schofield & Brustad, 2011; Von Wehren et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2017; Welsh & Clodman, 1980; Xu et al., 2019; Zellers et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020; Zhuang et al., 2019; Romero-Morales et al., 2019b) were included in this scoping review.

Figure 2: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis flow diagram.

Characteristics of sources of evidence

In grouping the included articles by publication type, narrative reviews were the most common (27.2%) followed by cohort studies (19.6%), case control studies (18.8%), randomised controlled trials (12.7%), cross-sectional studies (10.8%), case reports (3.8%), protocols (3.2%), systematic reviews (1.9%), clinical guidelines (1.9%) and one consensus statement (0.6%). The years of publication of included studies ranged from 1980 to 2021, with 2017 to 2020 producing the most publications. Table 3 provides the general characteristics of the reviewed studies, including year of publication, type of publication, terminology and tendinopathy location.

Note:

n, number; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

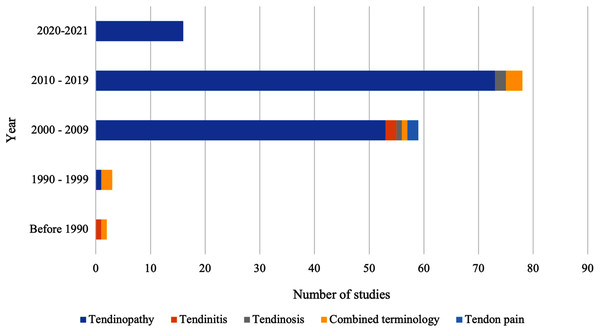

As highlighted in Fig. 3, the terminology used to describe tendon pain varied, with ‘tendinopathy’ being the most prevalent term used to describe tendon pain. Thus, during this scoping review, tendinopathy, will be used to describe pain located in the Achilles tendon that impairs function.

Figure 3: Terminology used to describe the clinical presentation of Achilles tendon pain and impaired function.

Results of individual sources of evidence

Clinical guidelines and consensus statements

Two of the included clinical guidelines (Carcia et al., 2010; Martin et al., 2018) discussed midportion Achilles tendinopathy, with one clinical guideline (Thomas et al., 2010) and one consensus statement (Xu et al., 2019) discussing insertional Achilles tendinopathy (Table 4). Clinical measures used to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy was consistent across the clinical guidelines and consensus statement, with location of pain being the main differentiating factor between diagnosing midportion or insertional tendinopathy. Common methods with which midportion tendinopathy was diagnosed included subjective reporting of pain located in the Achilles tendon 2–6 cm above the calcaneal insertion that is increased with tendon loading and reported tendon stiffness. Similarly, insertional tendinopathy was diagnosed via subjective reporting of pain and swelling at the calcaneal insertion of the Achilles tendon. Pain on palpation was utilised to confirm clinical diagnosis in both midportion and insertional tendinopathy. While additional objective tests for midportion tendinopathy included the ‘Painful Arc Sign’ and ‘Royal London Hospital Test’.

| Author | Year | Location | Subjective history | Clinical tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcia et al. (2010) | 2010 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test Single-leg heel Raise Hopping |

| Thomas et al. (2010) | 2010 | Insertional | Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| Martin et al. (2018) | 2018 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Xu et al. (2019) | 2019 | Insertional | Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with active dorsiflexion Silverskiold Test |

Note:

cm, centimetres.

Systematic reviews

All three included systematic reviews assessed midportion Achilles tendinopathy (Table 5) (Reiman et al., 2014; Hutchison et al., 2011; Magnussen, Dunn & Thomson, 2009). Subjective reporting of pain with tendon loading was included as a diagnostic feature of midportion Achilles tendinopathy in all three systematic reviews (Leung & Griffith, 2008; Hutchison et al., 2011; Magnussen, Dunn & Thomson, 2009). Two of the systematic reviews (Reiman et al., 2014; Hutchison et al., 2011) identified the location of tendon pain as 2–6 cm above the calcaneal insertion, with one (Magnussen, Dunn & Thomson, 2009) defining the location of tendon pain as 2–7 cm above the calcaneal insertion. Palpation of the Achilles tendon, passive dorsiflexion, pain with single-leg heel raise and pain hopping or jumping were included as clinical tests in all included systematic reviews (Reiman et al., 2014; Hutchison et al., 2011; Magnussen, Dunn & Thomson, 2009). Two of the systematic reviews (Reiman et al., 2014; Hutchison et al., 2011) included the ‘Painful Arc Sign’ and ‘Royal London Hospital Test’ as diagnostic measures for midportion Achilles tendinopathy.

| Author | Year | Sample size | Location | Subjective history | Clinical tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnussen, Dunn & Thomson (2009) | 2009 | 677 (M/F = 347/330) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion Single-leg heel raise Hopping |

| Hutchison et al. (2011) | 2011 | 578 (M/F = not specified) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test Reduced dorsiflexion Single-leg heel Raise Jump test |

| Reiman et al. (2014) | 2014 | 31 (M/F = 27/4) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test Pain with dorsiflexion Single-leg heel Raise Hopping |

Note:

cm, centimetres; M, male; F, female.

Randomised controlled trials

Table 6 highlights the characteristics of the included randomised controlled trials. Thirteen of the included studies (Boesen et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2006; Krogh et al., 2016; Mafi, Lorentzon & Alfredson, 2001; Mayer et al., 2007; Paoloni et al., 2004; Petersen, Welp & Rosenbaum, 2007; Rompe, Furia & Maffulli, 2009; Rompe et al., 2007; Roos et al., 2004; Solomons et al., 2020; Stergioulas et al., 2008; Van der Vlist et al., 2020) investigated midportion Achilles tendinopathy, one study (Rompe et al., 2008) investigated insertional Achilles tendinopathy, two studies (Gatz et al., 2020; Knobloch et al., 2007) investigated both insertional and midportion Achilles tendinopathy, and four studies (Bjordal, Lopes-Martins & Iversen, 2006; Ebbesen et al., 2018; Rasmussen et al., 2008; Silbernagel et al., 2001) did not specify a location of interest. All of the included randomised controlled trials used location of pain as a diagnostic feature of Achilles tendinopathy. Eight of the studies (Knobloch et al., 2007; Mafi, Lorentzon & Alfredson, 2001; Paoloni et al., 2004; Petersen, Welp & Rosenbaum, 2007; Rompe, Furia & Maffulli, 2009; Rompe et al., 2008; Roos et al., 2004; Stergioulas et al., 2008) which assessed midportion tendinopathy defined the location of pain as 2–6 cm above the calcaneal insertion, with three studies (Boesen et al., 2017; Krogh et al., 2016; Van der Vlist et al., 2020) defining midportion tendinopathy as 2–7 cm above the calcaneal insertion. Of the included studies, 17 included symptom duration as part of their diagnostic criteria, with various durations including four weeks (Roos et al., 2004), six weeks (Brown et al., 2006), two months (Gatz et al., 2020; Van der Vlist et al., 2020), three months (Boesen et al., 2017; Ebbesen et al., 2018; Mafi, Lorentzon & Alfredson, 2001; Paoloni et al., 2004; Petersen, Welp & Rosenbaum, 2007; Rasmussen et al., 2008; Silbernagel et al., 2001; Solomons et al., 2020) and six months (Mayer et al., 2007; Rompe, Furia & Maffulli, 2009; Rompe et al., 2008; Rompe et al., 2007; Stergioulas et al., 2008). Palpation was the most commonly used objective test, with 15 of the included studies (Bjordal, Lopes-Martins & Iversen, 2006; Boesen et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2006; Gatz et al., 2020; Krogh et al., 2016; Mafi, Lorentzon & Alfredson, 2001; Mayer et al., 2007; Paoloni et al., 2004; Petersen, Welp & Rosenbaum, 2007; Rasmussen et al., 2008; Rompe et al., 2008; Roos et al., 2004; Silbernagel et al., 2001; Stergioulas et al., 2008; Van der Vlist et al., 2020) using palpation to assess pain, localised tendon thickening or localised swelling. Four studies (Ebbesen et al., 2018; Knobloch et al., 2007; Rompe, Furia & Maffulli, 2009; Rompe et al., 2007) used solely subjective history to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy.

| Author | Year | Sample size | Location | Subjective history | Clinical tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mafi, Lorentzon & Alfredson (2001) | 2001 | 44 (M/F = 24/20) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Pain on palpation |

| Silbernagel et al. (2001) | 2001 | 49 (M/F = 36/13) | Not specified | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Pain on palpation Single leg heel raise Hopping Range of motion |

| Paoloni et al. (2004) | 2004 | 65 (M/F = 40/25) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Gradual onset of pain |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Hopping |

| Roos et al. (2004) | 2004 | 44 (M/F = 21/23) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>4 weeks) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Bjordal, Lopes-Martins & Iversen (2006) | 2006 | 7 (M/F = not specified) | Not specified | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Hopping |

| Brown et al. (2006) | 2006 | 26 (M/F = 17/9) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>6 weeks) Gradual onset of pain Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Single-leg heel raise Hopping |

| Knobloch et al. (2007) | 2007 | 20 (M/F = 11/9) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Not specified |

| Mayer et al. (2007) | 2007 | 31 (M/F = 31/0) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>6 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| Petersen, Welp & Rosenbaum (2007) | 2007 | 100 (M/F = 60/40) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Gradual onset of pain Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| Rompe et al. (2007) | 2007 | 75 (M/F = 29/46) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>6 months) Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Not specified |

| Rasmussen et al. (2008) | 2008 | 48 (M/F = 28/20) | Not specified | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with dorsiflexion |

| Rompe et al. (2008) | 2008 | 50 (M/F = 20/30) | Insertional | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Duration of symptoms (>6 months) |

Pain on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Stergioulas et al. (2008) | 2008 | 40 (M/F = 25/15) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>6 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Reduced active dorsiflexion |

| Rompe, Furia & Maffulli (2009) | 2009 | 68 (M/F = 30/38) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>6 months) Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Not specified |

| Krogh et al. (2016) | 2016 | 24 (M/F = 13/11) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| Boesen et al. (2017) | 2017 | 60 (M/F = 60/0) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Single-leg heel raise |

| Ebbesen et al. (2018) | 2018 | 44 (M/F = 25/19) | Not specified | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Not specified |

| Gatz et al. (2020) | 2020 | 42 (M/F = 20/22) | Insertional Midportion | Pain with tendon loading Duration of symptoms (>2 months) Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation |

| Solomons et al. (2020) | 2020 | 52 (M/F = 24/28) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Double leg heel raise Single leg heel raise Jump Hopping |

| Van der Vlist et al. (2020) | 2020 | 91 (M/F = 45/46) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>2 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

Note:

cm, centimetres; M, male; F, female.

Cohort studies

Of the included cohort studies, 21 were prospective cohort studies (Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Chester et al., 2008; Crill, Berlet & Hyer, 2014; Duthon et al., 2011; Jowett, Richmond & Bedi, 2018; Karjalainen et al., 2000; Khan et al., 2003; Knobloch, 2007; Knobloch et al., 2008; Maffulli et al., 2008; Mansur et al., 2019; McCormack et al., 2015; O’Neill et al., 2019; Oloff et al., 2015; Paavola et al., 2002; Paavola et al., 2000; Sayana & Maffulli, 2007; Silbernagel et al., 2007; Syvertson et al., 2017; Zhuang et al., 2019) and 10 were retrospective cohort studies (Alfredson & Spang, 2018; Barge-Caballero et al., 2008; Florit et al., 2019; Murawski et al., 2014; Stenson et al., 2018; Von Wehren et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2017; Welsh & Clodman, 1980; Zellers et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). Midportion Achilles tendinopathy was investigated in 15 studies (Chester et al., 2008; Crill, Berlet & Hyer, 2014; Duthon et al., 2011; Jowett, Richmond & Bedi, 2018; Knobloch et al., 2008; Lakshmanan & O’Doherty, 2004; Maffulli et al., 2008; Murawski et al., 2014; O’Neill et al., 2019; Paavola et al., 2002; Paavola et al., 2000; Sayana & Maffulli, 2007; Silbernagel et al., 2007; Syvertson et al., 2017; Von Wehren et al., 2019), insertional tendinopathy was investigated in eight studies (Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Mansur et al., 2019; McCormack et al., 2015; Stenson et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2017; Zellers et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020; Zhuang et al., 2019), both insertional and midportion tendinopathy was investigated in five studies (Alfredson & Spang, 2018; Karjalainen et al., 2000; Khan et al., 2003; Knobloch, 2007; Welsh & Clodman, 1980), and three studies did not specify tendinopathy location (Table 7) (Barge-Caballero et al., 2008; Florit et al., 2019; Oloff et al., 2015).

| Author | Year | Study design | Sample size | Location | Subjective history | Clinical tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh & Clodman (1980) | 1980 | Retrospective | 50 (M/F = 28/22) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–4 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Karjalainen et al. (2000) | 2000 | Prospective | 100 (M/F = 75/25) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (not specified) |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| Paavola et al. (2000) | 2000 | Prospective | 107 (M/F = 78/29) | Midportion | Pain with tendon loading Duration of symptoms (<6 months) |

Pain on palpation Range of motion Single-leg heel raise Single-leg stance |

| Paavola et al. (2002) | 2002 | Prospective | 42 (M/F = 29/13) | Midportion | Pain with tendon loading | Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Range of Motion Single-leg heel raise |

| Khan et al. (2003) | 2003 | Prospective | 45 (M/F = 27/18) | Insertional Midportion | Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness VISA-A |

Pain on palpation |

| Lakshmanan & O’Doherty (2004) | 2004 | Prospective | 15 (M/F = 12/3) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>6 months) |

Not specified |

| Knobloch (2007) | 2007 | Prospective | 64 (M/F = 39/25) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion)-midportion Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Not specified |

| Sayana & Maffulli (2007) | 2007 | Prospective | 34 (M/F = 18/16) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Silbernagel et al. (2007) | 2007 | Prospective | 37 (M/F = 20/17) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>2 months) Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Counter movement Jump Hopping Heel raise |

| Barge-Caballero et al. (2008) | 2008 | Retrospective | 242 (M/F = 191/51) | Not specified | Pain with tendon loading | Pain on palpation |

| Chester et al. (2008) | 2008 | Prospective | 16 (M/F = 11/5) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Knobloch et al. (2008) | 2008 | Prospective | 121 (M/F = 74/47) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Maffulli et al. (2008) | 2008 | Prospective | 45 (M/F = 29/16) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Duthon et al. (2011) | 2011 | Prospective | 14 (M/F = 11/3) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>1 year) |

Localised tendon thickening on palpation Range of Motion Plantarflexion strength Silfverskiold test |

| Crill, Berlet & Hyer (2014) | 2014 | Prospective | 25 (M/F = not specified) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–4 cm above calcaneal insertion) | Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Single-leg heel raise |

| Murawski et al. (2014) | 2014 | Retrospective | 32 (M/F = 21/11) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon Stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| McCormack et al. (2015) | 2015 | Prospective | 15 (M/F = 4/11) | Insertional | Location of pain (distal 2 cm) Duration of symptoms (>6 weeks) Pain with tendon loading VISA-A |

Pain on palpation |

| Oloff et al. (2015) | 2015 | Prospective | 26 (M/F = not specified) | Not specified | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>6 months) |

Not specified |

| Cheng, Zhang & Cai (2016) | 2016 | Prospective | 42 (M/F = 29/13) | Insertional | Location of pain (distal 2 cm) Duration of symptoms (>6 months) Swelling Pain with tendon loading |

Not specified |

| Syvertson et al. (2017) | 2017 | Prospective | 11 (M/F = 4/7) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation |

| Wei et al. (2017) | 2017 | Retrospective | 68 (M/F = 53/15) | Insertional | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>6 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Alfredson & Spang (2018) | 2018 | Retrospective | 771 (M/F = 481/290) | Insertional Midportion | Pain with tendon loading VISA-A |

Not specified |

| Jowett, Richmond & Bedi (2018) | 2018 | Prospective | 26 (M/F = 13/13) | Midportion | Location of pain Localised swelling Duration of symptoms (>6 months) |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| Stenson et al. (2018) | 2018 | Retrospective | 664 (M/F = 312/352) | Insertional | Location of pain (insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Range of motion |

| Florit et al. (2019) | 2019 | Retrospective | 110 (M/F = 103/7) | Not specified | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Pain with tendon loading tests (not specified) |

| Mansur et al. (2019) | 2019 | Prospective | 19 (M/F = 11/8) | Insertional | Location of pain (distal 2 cm) | Pain on palpation |

| O’Neill et al. (2019) | 2019 | Prospective | 16 (M/F = 11/5) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Von Wehren et al. (2019) | 2019 | Retrospective | 50 (M/F = 27/23) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>6 weeks) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Zellers et al. (2019) | 2019 | Retrospective | 56 (M/F = 25/31) | Insertional | Location of pain (insertion) | Pain on palpation |

| Zhuang et al. (2019) | 2019 | Prospective | 28 (M/F = 17/11) | Insertional | Location of pain (insertion) | Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Pain with resisted plantarflexion Reduced plantarflexion strength Heel raise test |

| Zhang et al. (2020) | 2020 | Retrospective | 33 (M/F = 31/2) | Insertional | Location of pain (insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Not specified |

Note:

cm, centimetres; M, male; F, female; VISA-A, Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles.

Location of pain was the most prominent diagnostic feature, with 26 studies (Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Chester et al., 2008; Crill, Berlet & Hyer, 2014; Duthon et al., 2011; Florit et al., 2019; Jowett, Richmond & Bedi, 2018; Karjalainen et al., 2000; Knobloch, 2007; Knobloch et al., 2008; Lakshmanan & O’Doherty, 2004; Maffulli et al., 2008; Mansur et al., 2019; McCormack et al., 2015; Murawski et al., 2014; O’Neill et al., 2019; Oloff et al., 2015; Sayana & Maffulli, 2007; Silbernagel et al., 2007; Stenson et al., 2018; Syvertson et al., 2017; Von Wehren et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2017; Welsh & Clodman, 1980; Zellers et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020; Zhuang et al., 2019) using it as a criteria to diagnose both midportion and insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Midportion tendinopathy was defined as an area 2–4 cm above the calcaneal insertion in two studies (Crill, Berlet & Hyer, 2014; Welsh & Clodman, 1980), 2–6 cm above the calcaneal insertion in six studies (Chester et al., 2008; Knobloch, 2007; Knobloch et al., 2008; Maffulli et al., 2008; Sayana & Maffulli, 2007; Syvertson et al., 2017), and 2–7 cm above the calcaneal insertion in one study (Murawski et al., 2014). Insertional tendinopathy was defined as the distal 2 cm in three studies (Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Mansur et al., 2017; McCormack et al., 2015), and the Achilles ‘insertion’ in five studies (Knobloch, 2007; Stenson et al., 2018; Zellers et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020; Zhuang et al., 2019). Pain with tendon loading was utilised as a diagnostic criteria in 18 studies (Alfredson & Spang, 2018; Barge-Caballero et al., 2008; Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Florit et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2003; Knobloch, 2007; Maffulli et al., 2008; McCormack et al., 2015; Murawski et al., 2014; O’Neill et al., 2019; Paavola et al., 2002; Paavola et al., 2000; Sayana & Maffulli, 2007; Silbernagel et al., 2007; Syvertson et al., 2017; Von Wehren et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2017; Welsh & Clodman, 1980), and duration of symptoms was utilised in 16 studies (Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Chester et al., 2008; Duthon et al., 2011; Jowett, Richmond & Bedi, 2018; Karjalainen et al., 2000; Knobloch et al., 2008; Lakshmanan & O’Doherty, 2004; McCormack et al., 2015; O’Neill et al., 2019; Oloff et al., 2015; Paavola et al., 2000; Silbernagel et al., 2007; Stenson et al., 2018; Von Wehren et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). Duration of symptoms varied significantly with studies defining tendinopathy as symptoms lasting less than 6 months (Paavola et al., 2000), more than 6 weeks (McCormack et al., 2015; Von Wehren et al., 2019), more than 2 months (Silbernagel et al., 2007), more than three months (Chester et al., 2008; Knobloch et al., 2008; O’Neill et al., 2019; Stenson et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020), more than six months (Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Jowett, Richmond & Bedi, 2018; Lakshmanan & O’Doherty, 2004; Oloff et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2017), and more than 1 year (Duthon et al., 2011). As with the previous studies, the most common objective test for diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy was palpation, with 23 studies utilising it as a diagnostic criteria (Barge-Caballero et al., 2008; Chester et al., 2008; Crill, Berlet & Hyer, 2014; Duthon et al., 2011; Florit et al., 2019; Jowett, Richmond & Bedi, 2018; Karjalainen et al., 2000; Khan et al., 2003; Knobloch et al., 2008; Maffulli et al., 2008; Mansur et al., 2019; McCormack et al., 2015; Murawski et al., 2014; O’Neill et al., 2019; Paavola et al., 2002; Paavola et al., 2000; Sayana & Maffulli, 2007; Syvertson et al., 2017; Von Wehren et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2017; Welsh & Clodman, 1980; Zellers et al., 2019; Zhuang et al., 2019). Six studies used only subjective measures for diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy (Alfredson & Spang, 2018; Cheng, Zhang & Cai, 2016; Knobloch, 2007; Lakshmanan & O’Doherty, 2004; Oloff et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2020).

Case-control studies

Of the 30 case-control studies, one (Chimenti et al., 2016) investigated insertional Achilles tendinopathy, 15 studies (Hutchison et al., 2013; Abate & Salini, 2019; Azevedo et al., 2009; Creaby et al., 2017; Gärdin et al., 2016; Lohrer & Nauck, 2009; Maffulli et al., 2003; Nadeau et al., 2016; Neeter et al., 2003; Pingel et al., 2013; Reid et al., 2012; Romero-Morales et al., 2019a; Ryan et al., 2009; Sengkerij et al., 2009; Romero-Morales et al., 2019b) investigated midportion Achilles tendinopathy, nine studies (Chimenti et al., 2020; Coombes et al., 2018; Eckenrode, Kietrys & Stackhouse, 2019; Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2018; Ooi et al., 2015; Rabello et al., 2020; Reiter et al., 2004; Verrall, Schofield & Brustad, 2011; Zhang et al., 2017) investigated both insertional and midportion Achilles tendinopathy, with five studies (Cassel et al., 2018; Holmes & Lin, 2006; Jewson et al., 2017; Leung & Griffith, 2008; De Mesquita et al., 2018) not specifying tendinopathy location (Table 8). As with the previous study types, the most commonly used diagnostic feature was location of pain, which was utilised in 27 of the case-control studies (Hutchison et al., 2013; Abate & Salini, 2019; Chimenti et al., 2016; Chimenti et al., 2020; Coombes et al., 2018; Creaby et al., 2017; Eckenrode, Kietrys & Stackhouse, 2019; Gärdin et al., 2016; Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2018; Holmes & Lin, 2006; Jewson et al., 2017; Leung & Griffith, 2008; Lohrer & Nauck, 2009; Nadeau et al., 2016; Neeter et al., 2003; De Mesquita et al., 2018; Ooi et al., 2015; Pingel et al., 2013; Rabello et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2012; Reiter et al., 2004; Romero-Morales et al., 2019a; Ryan et al., 2009; Sengkerij et al., 2009; Verrall, Schofield & Brustad, 2011; Zhang et al., 2017; Romero-Morales et al., 2019b). Insertional tendinopathy was defined as the distal 2 cm of the Achilles tendon in three studies (Chimenti et al., 2020; Rabello et al., 2020; Verrall, Schofield & Brustad, 2011). Midportion tendinopathy was defined as 2–6 cm above the calcaneal insertion in eight studies (Hutchison et al., 2013; Chimenti et al., 2020; Neeter et al., 2003; Rabello et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2009; Verrall, Schofield & Brustad, 2011; Zhang et al., 2017), 2–7 cm above the calcaneal insertion in three studies (Gärdin et al., 2016; Lohrer & Nauck, 2009; Sengkerij et al., 2009), and the middle third of the tendon in one study (Nadeau et al., 2016). Additionally, duration of symptoms was commonly used to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy, with variations in the criteria. Achilles tendinopathy was defined as duration of symptoms of less than three months in one study (Neeter et al., 2003), greater than four weeks in two studies (Jewson et al., 2017; Nadeau et al., 2016), greater than two months in one study (De Mesquita et al., 2018), greater than three months in eight studies (Chimenti et al., 2020; Coombes et al., 2018; Eckenrode, Kietrys & Stackhouse, 2019; Ooi et al., 2015; Romero-Morales et al., 2019a; Ryan et al., 2009; Verrall, Schofield & Brustad, 2011; Romero-Morales et al., 2019b), and greater than six months in three studies (Gärdin et al., 2016; Leung & Griffith, 2008; Pingel et al., 2013). Pain with tendon loading was included as a diagnostic criteria in 18 studies (Abate & Salini, 2019; Azevedo et al., 2009; Cassel et al., 2018; Chimenti et al., 2016; Chimenti et al., 2020; Creaby et al., 2017; Eckenrode, Kietrys & Stackhouse, 2019; Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2018; Holmes & Lin, 2006; Jewson et al., 2017; Lohrer & Nauck, 2009; Reid et al., 2012; Reiter et al., 2004; Romero-Morales et al., 2019a; Ryan et al., 2009; Sengkerij et al., 2009; Verrall, Schofield & Brustad, 2011; Romero-Morales et al., 2019b). One study did not specify a subjective criteria to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy (Maffulli et al., 2003). Similar to previous study designs, palpation was the most common clinical test to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy, with it being used in 26 studies (Hutchison et al., 2013; Abate & Salini, 2019; Azevedo et al., 2009; Cassel et al., 2018; Chimenti et al., 2016; Chimenti et al., 2020; Coombes et al., 2018; Creaby et al., 2017; Eckenrode, Kietrys & Stackhouse, 2019; Gärdin et al., 2016; Holmes & Lin, 2006; Leung & Griffith, 2008; Lohrer & Nauck, 2009; Maffulli et al., 2003; Nadeau et al., 2016; Neeter et al., 2003; De Mesquita et al., 2018; Ooi et al., 2015; Pingel et al., 2013; Reid et al., 2012; Reiter et al., 2004; Romero-Morales et al., 2019a; Sengkerij et al., 2009; Verrall, Schofield & Brustad, 2011; Zhang et al., 2017; Romero-Morales et al., 2019b). Four studies relied only on subjective measures to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy (Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2018; Jewson et al., 2017; Rabello et al., 2020; Ryan et al., 2009).

| Author | Year | Sample size | Location | Subjective history | Clinical tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maffulli et al. (2003) | 2003 | 24 (M/F = 24/0) | Midportion | Not specified | Pain on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Neeter et al. (2003) | 2003 | 25 (M/F = 15/10) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (<3 months) |

Pain on palpation Range of motion Single-leg heel raise |

| Reiter et al. (2004) | 2004 | 35 (M/F = 30/5) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading VISA-A |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| Holmes & Lin (2006) | 2006 | 82 (M/F = 44/38) | Not specified | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Leung & Griffith (2008) | 2008 | 71 (M/F = 31/40) | Not specified | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>6 months) |

Pain on palpation Localised thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Azevedo et al. (2009) | 2009 | 42 (M/F = 32/10) | Midportion | Gradual onset of pain Tendon stiffness Swelling Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Painful Arc Sign |

| Lohrer & Nauck (2009) | 2009 | 119 (M/F = not specified) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Ryan et al. (2009) | 2009 | 48 (M/F = 48/0) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Not specified |

| Sengkerij et al. (2009) | 2009 | 25 (M/F = 16/9) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Verrall, Schofield & Brustad (2011) | 2011 | 190 (M/F = 108/82) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (distal 2 cm) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Reid et al. (2012) | 2012 | 36 (M/F = not specified) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Hutchison et al. (2013) | 2013 | 21 (M/F = 9/12) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test Pain with dorsiflexion Single-leg heel raise Hopping |

| Pingel et al. (2013) | 2013 | 18 (M/F = 10/8) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>6 months) |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Ooi et al. (2015) | 2015 | 240 (M/F = 180/60) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Chimenti et al. (2016) | 2016 | 40 (M/F = 20/20) | Insertional | Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Gärdin et al. (2016) | 2016 | 30 (M/F = 12/18) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>6 months) |

Pain on palpation |

| Nadeau et al. (2016) | 2016 | 43 (M/F = 30/13) | Midportion | Location of pain (middle third) Duration of symptoms (>4 weeks) VISA-A |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion Pain with resisted plantarflexion Single-leg heel raise Hopping |

| Creaby et al. (2017) | 2017 | 25 (M/F = 25/0) | Midportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Hopping |

| Jewson et al. (2017) | 2017 | 35 (M/F = 22/13) | Not specified | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>4 weeks) Pain with tendon loading |

Not specified |

| Zhang et al. (2017) | 2017 | 37 (M/F = 26/11) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (insertion) |

Pain on palpation Pain with resisted plantarflexion |

| Cassel et al. (2018) | 2018 | 182 (M/F = 113/69) | Not specified | Pain with tendon loading | Pain on palpation |

| Coombes et al. (2018) | 2018 | 67 (M/F = 37/30) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) |

Pain on palpation Single-leg heel raise |

| Hernández-Sánchez et al. (2018) | 2018 | 210 (M/F = 148/62) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Not specified |

| De Mesquita et al. (2018) | 2018 | 67 (M/F = 41/26) | Not specified | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>2 months) |

Pain on palpation |

| Abate & Salini (2019) | 2019 | 64 (M/F = 40/24) | Midportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Eckenrode, Kietrys & Stackhouse (2019) | 2019 | 41 (M/F = 19/22) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Single-leg heel raise |

| Romero-Morales et al. (2019a) | 2019 | 141 (M/F = 116/25) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Romero-Morales et al. (2019b) | 2019 | 143 (M/F = not specified) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Chimenti et al. (2020) | 2020 | 46 (M/F = 30/16) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (distal 2 cm) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation |

| Rabello et al. (2020) | 2020 | 46 (M/F = 30/16) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (distal 2 cm) |

Not specified |

Note:

cm, centimetres; M, male; F, female; VISA-A, Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles.

Cross-sectional studies

Table 9 provides an overview of the 17 included cross-sectional studies, with 10 studies (De Jonge et al., 2011; De Marchi et al., 2018; Divani et al., 2010; Finnamore et al., 2019; Maffulli et al., 2008; Praet et al., 2018; Santamato et al., 2019; Scholes et al., 2018; Van der Vlist et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2012) investigating midportion Achilles tendinopathy, four studies (Docking et al., 2015; Kragsnaes et al., 2014; Turner et al., 2020; Vallance et al., 2020) investigating both insertional and midportion Achilles tendinopathy, and three studies (Aiyegbusi, Tella & Sanusi, 2020; Longo et al., 2009; Mantovani et al., 2020) not specifying tendinopathy location. Once again, location of pain was the most common subjective measure to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy, with 12 studies utilising it as a diagnostic criteria (De Jonge et al., 2011; De Marchi et al., 2018; Kragsnaes et al., 2014; Maffulli et al., 2008; Mantovani et al., 2020; Praet et al., 2018; Chester et al., 2008; Scholes et al., 2018; Turner et al., 2020; Vallance et al., 2020; Van der Vlist et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2012). Midportion Achilles tendinopathy was defined as 2–6 cm above the calcaneal insertion in four studies (De Marchi et al., 2018; Maffulli et al., 2008; Praet et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2012), and 2–7 cm above the calcaneal insertion in one study (Van der Vlist et al., 2020). Similarly, 12 studies included duration of symptoms as a diagnostic criteria, with durations of symptoms including greater than four weeks (Santamato et al., 2019), greater than two months (Praet et al., 2018; Van der Vlist et al., 2020), greater than three months (Finnamore et al., 2019; Maffulli et al., 2008; Mantovani et al., 2020; Scholes et al., 2018; Turner et al., 2020; Vallance et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2012), greater than four months (Kragsnaes et al., 2014), and greater than six months (De Marchi et al., 2018). Pain with tendon loading was the next most common subjective diagnostic measure, with nine studies including it as a diagnostic measure (De Marchi et al., 2018; Docking et al., 2015; Finnamore et al., 2019; Maffulli et al., 2008; Scholes et al., 2018; Turner et al., 2020; Vallance et al., 2020; Van der Vlist et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2012). One study (Divani et al., 2010) did not report subjective measures to confirm the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy. The most common clinical test included palpation, with nine studies using palpation to clinically diagnose Achilles tendinopathy (Divani et al., 2010; Finnamore et al., 2019; Kragsnaes et al., 2014; Longo et al., 2009; Maffulli et al., 2008; Mantovani et al., 2020; Praet et al., 2018; Van der Vlist et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2012). Four studies (Aiyegbusi, Tella & Sanusi, 2020; Longo et al., 2009; Santamato et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2012) included the Royal London Hospital Test as a clinical measure of Achilles tendinopathy, with four studies (De Jonge et al., 2011; De Marchi et al., 2018; Scholes et al., 2018; Turner et al., 2020) not specifying the clinical tests utilised to confirm the diagnosis.

| Author | Year | Sample size | Location | Subjective history | Clinical tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maffulli et al. (2008) | 2008 | 50 (M/F = 50/0) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Longo et al. (2009) | 2009 | 178 (M/F = 110/68) | Not specified | VISA-A | Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Divani et al. (2010) | 2010 | 26 (M/F = 17/9) | Midportion | Not specified | Pain on palpation |

| De Jonge et al. (2011) | 2011 | 107 (M/F = 51/56) | Midportion | Location of pain (above calcaneal insertion) | Not specified |

| Wang et al. (2012) | 2012 | 17 (M/F = 17/0) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading VISA-A |

Pain on palpation Royal London Hospital Test |

| Kragsnaes et al. (2014) | 2014 | 50 (M/F = 27/23) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>4 months) |

Pain on palpation |

| Docking et al. (2015) | 2015 | 21 (M/F = 20/1) | Insertional Midportion | Pain with tendon loading | Single-leg heel raise Hopping |

| De Marchi et al. (2018) | 2018 | 27 (M/F = 19/8) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>6 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Not specified |

| Praet et al. (2018) | 2018 | 20 (M/F = 13/7) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>2 months) |

Pain on palpation |

| Scholes et al. (2018) | 2018 | 21 (M/F = 21/0) | Midportion | Location of pain (midportion) Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Not specified |

| Finnamore et al. (2019) | 2019 | 25 (M/F = 12/13) | Midportion | Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Santamato et al. (2019) | 2019 | 12 (M/F = 7/5) | Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>4 weeks) |

Reduced ROM Pain during AROM Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Aiyegbusi, Tella & Sanusi (2020) | 2020 | 85 (M/F = 56/29) | Not specified | VISA-A | Royal London Hospital Test |

| Mantovani et al. (2020) | 2020 | 19 (M/F = 13/6) | Not specified | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) VISA-A (<80) |

Pain on palpation |

| Turner et al. (2020) | 2020 | 15 (M/F = 8/7) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Gradual onset of pain Pain with tendon loading |

Not specified |

| Vallance et al. (2020) | 2020 | 86 (M/F = 86/0) | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Duration of symptoms (>3 months) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Single-leg heel raise Hopping |

| Van der Vlist et al. (2020) | 2020 | 28 (M/F = 16/12) | Midportion | Location of pain (2–7 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms (>2 months) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

Note:

cm, centimetres; M, male; F, female; VISA-A, Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles.

Narrative reviews

Of the 43 narrative reviews included in the scoping review, seven studies investigated insertional Achilles tendinopathy (Aldridge, 2004; Benazzo, Todesca & Ceciliani, 1997; Chimenti et al., 2017; Den Hartog, 2009; Hu & Flemister, 2008; Irwin, 2010; Maffulli et al., 2019), 18 studies investigated midportion Achilles tendinopathy (Alfredson, 2003; Alfredson & Cook, 2007; Bains & Porter, 2006; Courville, Coe & Hecht, 2009; Feilmeier, 2017; Järvinen et al., 2001; Kader et al., 2002; Longo, Ronga & Maffulli, 2009; Maffulli & Kader, 2002; Maffulli et al., 2012; Maffulli, Sharma & Luscombe, 2004; Maffulli, Via & Oliva, 2014; McShane, Ostick & McCabe, 2007; Paavola et al., 2002; Scott, Huisman & Khan, 2011; Sharma & Maffulli, 2006; Simpson & Howard, 2009; Tan & Chan, 2008), 13 studies investigated both insertional and midportion Achilles tendinopathy (Aronow, 2005; Asplund & Best, 2013; Bhatty, Khan & Zubairy, 2019; Chazan, 1998; Cook, Khan & Purdam, 2002; Fredericson, 1996; Furia & Rompe, 2007; Horn & McCollum, 2015; Jukes, Scott & Solan, 2020; Maffulli, Giai Via & Oliva, 2015; Maffulli et al., 2020; Pedowitz & Beck, 2017; Saini et al., 2015), and five studies did not specify tendinopathy location (Table 10) (Millar et al., 2021; Baskerville et al., 2018; Maffulli, Giuseppe Longo & Denaro, 2012; Nichols, 1989; Sorosky et al., 2004). The most common subjective diagnostic criteria for diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy was pain with tendon loading, with all 43 included reviews utilising as a diagnostic criteria (Millar et al., 2021; Aldridge, 2004; Alfredson, 2003; Alfredson & Cook, 2007; Aronow, 2005; Asplund & Best, 2013; Bains & Porter, 2006; Baskerville et al., 2018; Benazzo, Todesca & Ceciliani, 1997; Bhatty, Khan & Zubairy, 2019; Chazan, 1998; Chimenti et al., 2017; Cook, Khan & Purdam, 2002; Courville, Coe & Hecht, 2009; Den Hartog, 2009; Feilmeier, 2017; Fredericson, 1996; Furia & Rompe, 2007; Horn & McCollum, 2015; Hu & Flemister, 2008; Irwin, 2010; Järvinen et al., 2001; Jukes, Scott & Solan, 2020; Kader et al., 2002; Longo, Ronga & Maffulli, 2009; Maffulli, Giai Via & Oliva, 2015; Maffulli, Giuseppe Longo & Denaro, 2012; Maffulli & Kader, 2002; Maffulli et al., 2020; Maffulli et al., 2012; Maffulli et al., 2019; Maffulli, Sharma & Luscombe, 2004; Maffulli, Via & Oliva, 2014; McShane, Ostick & McCabe, 2007; Nichols, 1989; Paavola et al., 2002; Pedowitz & Beck, 2017; Saini et al., 2015; Scott, Huisman & Khan, 2011; Sharma & Maffulli, 2006; Simpson & Howard, 2009; Sorosky et al., 2004; Tan & Chan, 2008). Location of pain was included as a diagnostic criteria of Achilles tendinopathy in 31 studies, with midportion tendinopathy defined as ‘midportion’ in two studies (Saini et al., 2015; Tan & Chan, 2008), distal 5 cm of the Achilles tendon in one study (Nichols, 1989), 2–5 cm above the calcaneal insertion in three studies (Bains & Porter, 2006; Furia & Rompe, 2007; Simpson & Howard, 2009), 2–6 cm above the calcaneal insertion in 13 studies (Alfredson, 2003; Asplund & Best, 2013; Feilmeier, 2017; Fredericson, 1996; Horn & McCollum, 2015; Kader et al., 2002; Longo, Ronga & Maffulli, 2009; Maffulli, Giai Via & Oliva, 2015; Maffulli & Kader, 2002; Maffulli, Sharma & Luscombe, 2004; Maffulli, Via & Oliva, 2014; Pedowitz & Beck, 2017; Sharma & Maffulli, 2006), and 4–6 cm above the calcaneal insertion in one study (Maffulli et al., 2012). The third most common subjective criteria reported was tendon stiffness, with 24 studies including it as a diagnostic criteria (Millar et al., 2021; Alfredson, 2003; Alfredson & Cook, 2007; Asplund & Best, 2013; Bains & Porter, 2006; Baskerville et al., 2018; Benazzo, Todesca & Ceciliani, 1997; Chazan, 1998; Chimenti et al., 2017; Cook, Khan & Purdam, 2002; Courville, Coe & Hecht, 2009; Feilmeier, 2017; Fredericson, 1996; Hu & Flemister, 2008; Irwin, 2010; Jukes, Scott & Solan, 2020; Kader et al., 2002; Maffulli, Giuseppe Longo & Denaro, 2012; Maffulli et al., 2020; Maffulli et al., 2019; McShane, Ostick & McCabe, 2007; Nichols, 1989; Pedowitz & Beck, 2017; Tan & Chan, 2008). As with previous study types, the most common clinical test used to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy was palpation, with all 43 included reviews including it as a clinical measure (Millar et al., 2021; Aldridge, 2004; Alfredson, 2003; Alfredson & Cook, 2007; Aronow, 2005; Asplund & Best, 2013; Bains & Porter, 2006; Baskerville et al., 2018; Benazzo, Todesca & Ceciliani, 1997; Bhatty, Khan & Zubairy, 2019; Chazan, 1998; Chimenti et al., 2017; Cook, Khan & Purdam, 2002; Courville, Coe & Hecht, 2009; Den Hartog, 2009; Feilmeier, 2017; Fredericson, 1996; Furia & Rompe, 2007; Horn & McCollum, 2015; Hu & Flemister, 2008; Irwin, 2010; Järvinen et al., 2001; Jukes, Scott & Solan, 2020; Kader et al., 2002; Longo, Ronga & Maffulli, 2009; Maffulli, Giai Via & Oliva, 2015; Maffulli, Giuseppe Longo & Denaro, 2012; Maffulli & Kader, 2002; Maffulli et al., 2020; Maffulli et al., 2012; Maffulli et al., 2019; Maffulli, Sharma & Luscombe, 2004; Maffulli, Via & Oliva, 2014; McShane, Ostick & McCabe, 2007; Nichols, 1989; Paavola et al., 2002; Pedowitz & Beck, 2017; Saini et al., 2015; Scott, Huisman & Khan, 2011; Sharma & Maffulli, 2006; Simpson & Howard, 2009; Sorosky et al., 2004; Tan & Chan, 2008). There was then significant variation in other clinical tests used to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy, with nine studies including the Painful Arc Sign (Millar et al., 2021; Aronow, 2005; Feilmeier, 2017; Horn & McCollum, 2015; Kader et al., 2002; Longo, Ronga & Maffulli, 2009; Maffulli, Giuseppe Longo & Denaro, 2012; Maffulli & Kader, 2002; Maffulli et al., 2020), seven studies including reduced range of motion (Bhatty, Khan & Zubairy, 2019; Chazan, 1998; Chimenti et al., 2017; Furia & Rompe, 2007; Hu & Flemister, 2008; Maffulli et al., 2012; Nichols, 1989), six studies including the Royal London Hospital Test (Millar et al., 2021; Feilmeier, 2017; Horn & McCollum, 2015; Jukes, Scott & Solan, 2020; Longo, Ronga & Maffulli, 2009; Maffulli et al., 2020), and six studies including pain whilst hopping as a clinical diagnostic criteria (Millar et al., 2021; Alfredson & Cook, 2007; Bains & Porter, 2006; Cook, Khan & Purdam, 2002; Feilmeier, 2017; Nichols, 1989).

| Author | Year | Location | Subjective history | Clinical tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nichols (1989) | 1989 | Not specified | Location of pain (Distal 5 cm) Tendon stiffness Pain with tendon loading Gradual onset of pain Change in activity |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Reduced ROM Hopping |

| Fredericson (1996) | 1996 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Benazzo, Todesca & Ceciliani (1997) | 1997 | Insertional | Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation |

| Chazan (1998) | 1998 | Insertional Midportion | Gradual onset of pain Tendon stiffness Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion Pain with resisted plantarflexion Reduced ROM |

| Järvinen et al. (2001) | 2001 | Midportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Cook, Khan & Purdam (2002) | 2002 | Insertional Midportion | Gradual onset of pain Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness Change in activity VISA-A |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Single-leg heel raise Hopping |

| Kader et al. (2002) | 2002 | Midportion | Gradual onset of pain Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms Tendon stiffness Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Painful Arc Sign |

| Maffulli & Kader (2002) | 2002 | Midportion | Gradual onset of pain Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Duration of symptoms Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Painful Arc Sign |

| Paavola et al. (2002) | 2002 | Midportion | Pain with tendon loading Duration of symptoms |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Alfredson (2003) | 2003 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Aldridge (2004) | 2004 | Insertional | Pain with tendon loading | Pain on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion |

| Maffulli, Sharma & Luscombe (2004) | 2004 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Sorosky et al. (2004) | 2004 | Not specified | Gradual onset of pain Pain with tendon loading Change in training |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion Pain with resisted plantarflexion |

| Aronow (2005) | 2005 | Insertional Midportion | Pain with tendon loading | Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion (insertional) Painful Arc Sign (midportion) Single-leg Heel Raise |

| Bains & Porter (2006) | 2006 | Midportion | Gradual onset of pain Location of pain (2–5 cm above calcaneal insertion) Tendon stiffness Pain with tendon loading Change in training VISA-A |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Hopping on the spot Forward hopping 6m hop test |

| Sharma & Maffulli (2006) | 2006 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Alfredson & Cook (2007) | 2007 | Midportion | Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Localised swelling on palpation Single-leg Heel Raise Hopping on the spot Forward hopping |

| Furia & Rompe (2007) | 2007 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–5 cm above calcaneal insertion) - midportion Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion (insertional) Reduced ROM |

| McShane, Ostick & McCabe (2007) | 2007 | Midportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Single-leg heel raise |

| Hu & Flemister (2008) | 2008 | Insertional | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion Reduced ROM Silfverskiold test |

| Tan & Chan (2008) | 2008 | Midportion | Location of pain (midportion) Duration of pain (>2 weeks) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Single-leg heel raise |

| Courville, Coe & Hecht (2009) | 2009 | Midportion | Pain with tendon loading Location of pain Tendon stiffness Change in activity |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Den Hartog (2009) | 2009 | Insertional | Gradual onset of pain Duration of symptoms Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Longo, Ronga & Maffulli (2009) | 2009 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Simpson & Howard (2009) | 2009 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–5 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Swelling Change in activity |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Reduced flexibility in hamstring and calf |

| Irwin (2010) | 2010 | Insertional | Location of pain (calcaneal tuberosity) Swelling Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Scott, Huisman & Khan (2011) | 2011 | MIdportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Swelling |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation |

| Maffulli et al. (2012) | 2012 | Midportion | Location of pain (4–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading Swelling Change in activity |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Reduced ROM |

| Maffulli, Giuseppe Longo & Denaro (2012) | 2012 | Not specified | Gradual onset of pain Tendon stiffness Pain with tendon loading Swelling VISA-A |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Painful Arc Sign |

| Asplund & Best (2013) | 2013 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Maffulli, Via & Oliva (2014) | 2014 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Single-leg heel raise |

| Horn & McCollum (2015) | 2015 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Localised swelling on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Maffulli, Giai Via & Oliva (2015) | 2015 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (insertion) Swelling Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation |

| Saini et al. (2015) | 2015 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (midportion) Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with dorsiflexion and plantarflexion |

| Chimenti et al. (2017) | 2017 | Insertional | Location of pain (distal 2 cm) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion Pain with resisted plantarflexion Reduced ROM |

| Feilmeier (2017) | 2017 | Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Swelling Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness Change in activity VISA-A |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test Single-leg Heel Raise Hopping |

| Pedowitz & Beck (2017) | 2017 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain (2–6 cm above calcaneal insertion) Location of pain (insertion) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Single leg heel raise |

| Baskerville et al. (2018) | 2018 | Not specified | Gradual onset of pain Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Pain with passive and active movement Reduced strength |

| Bhatty, Khan & Zubairy (2019) | 2019 | Insertional Midportion | Pain with tendon loading | Pain on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Pain with passive dorsiflexion (insertional) Pain with resisted plantarflexion Reduced ROM |

| Maffulli et al. (2019) | 2019 | Insertional | Location of pain (distal 2 cm) Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation |

| Jukes, Scott & Solan (2020) | 2020 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness Duration of symptoms |

Pain on palpation Localised tendon thickening on palpation Localised swelling on palpation Royal London Hospital Test Silfverskiold test |

| Maffulli et al. (2020) | 2020 | Insertional Midportion | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Localised swelling Tendon stiffness |

Pain on palpation Painful Arc Sign Royal London Hospital Test |

| Millar et al. (2021) | 2021 | Not specified | Location of pain Pain with tendon loading Tendon stiffness |