The Slavcleft: a three-center study of the outcome of treatment of cleft lip and palate. Nasolabial appearance

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Spyridon Papageorgiou

- Subject Areas

- Dentistry, Pediatrics, Surgery and Surgical Specialties

- Keywords

- Cleft lip and palate, Nasolabial appearance, Esthetics, Slavs

- Copyright

- © 2021 Stebel et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2021. The Slavcleft: a three-center study of the outcome of treatment of cleft lip and palate. Nasolabial appearance. PeerJ 9:e10631 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10631

Abstract

Background

There is a multitude of protocols of treatment of cleft lip and palate (CLP) worldwide differing in number of operations, surgical techniques, and timings of surgeries. Despite, facial appearance in subjects with CLP is rarely ideal and residual stigmata are easy to notice in many patients irrespective of the protocol. The prospective controlled investigations are optimal for comparing effectiveness of treatment protocols. Because prospective studies are very challenging to perform in CLP field, it is reasonable to retrospectively assess different surgical protocols to identify the promising ones and then to test them in a prospective way.

Methods

Our objective was to assess the nasolabial appearance in a preadolescent Slavic population with unilateral cleft lip and palate (UCLP) by using the 0–200 numeric scale with reference photographs. Patients treated in Warsaw, Poland (n = 32), Prague, Czech Republic (n = 26) and Bratislava, Slovakia (n = 17) were included in this retrospective study. Each cleft center used a unique surgical protocol. Two panels of professional raters (n = 7) and laypeople (n = 10) scored blindly the nasolabial esthetics on cropped frontal and profile images with cropped reference photograph present on the same slide. Intra- and inter-rater agreement was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha, intraclass correlation coefficients, t-tests, and Bland–Altman plots. Inter-group differences were evaluated with one-way ANOVA and regression analysis.

Results

The agreement within and between raters was acceptable. We found that patients treated in Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava showed comparable nasolabial appearance on frontal and profile photographs when judged by both professional raters (p > 0.05) and laypeople (p > 0.05). Regression analysis did not identify influence of gender, group (i.e., Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava), age at lip repair, surgeon, and age at photographic assessment on esthetic outcome (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

This study showed that none of the surgical protocols showed superiority to produce good nasolabial appearance.

Introduction

Many children and teenagers with cleft lip and palate (CLP) are confronted with comments, questions, staring and teasing related to poor facial appearance and/or speech problems. These behaviors can lead to worse self-perception, lower self-esteem and psychological problems in individuals with CLP (Hunt et al., 2005).

One of the goals of treatment of CLP is to improve facial esthetics and function. However, an association between facial appearance and self-perception or satisfaction with treatment is complex. For example, participants of the Eurocleft study who were most satisfied with their treatment did not demonstrate the best esthetic outcome measured objectively by independent judges (Semb et al., 2005). Meyer-Marcotty & Stellzig-Eisenhauer (2009) showed, in turn, that the self-perception of patients affected by CLP did not correlate with objective results or with how others perceived them. Kuijpers et al. (2021) found that objectively rated nasolabial esthetics was weakly associated with the extent of deformation of nasolabial shape. Despite complexity of the relationship between facial appearance and psychosocial well-being, it is widely recognized that assessment of effectiveness of different protocols of treatment of CLP should include evaluation of nasolabial appearance (Brattström et al., 2005; Mercado et al., 2011). Therefore, the main objective of the current part of the Slavcleft is comparison of nasolabial esthetics in patients with complete unilateral cleft lip and palate treated in three cleft centers—Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava—using different surgical protocols. The H10 hypothesis was that the nasolabial esthetics in all groups was comparable. An additional objective of the study was to compare results of esthetic rating carried out by professionals and laypeople. The H20 hypothesis was that rating of professionals and laypeople was comparable.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

The institutional bioethics committees of (1) Institute of Mother and Child (IMC), Warsaw, (2) Medical Faculty of Charles University, Prague, and (3) University Hospital, Bratislava approved this investigation. The reference numbers are respectively: (1) 30/2016, (2) EK-VP/O1/0/2020, and (3) EK/O15/2O2O. All subjects writtenly consented to participate in this study.

Subjects

Nasolabial appearance was evaluated on frontal and profile images of 75 children with complete unilateral cleft lip and palate (UCLP) who were treated in three centers (Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava) using different surgical protocols. The images were taken between 2000 and 2012 under standardized conditions for each cleft center (i.e., conditions such as the use of the same background or lightning were standardized within the center; conditions between centers were not standardized). Information about the type of camera, lenses and settings was missing. Description of treatment protocols was presented in the 1st part of Slavcleft study—Table 1.

| Procedure | Warsaw | Prague | Bratislava |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant orthopedics | no | no | yes (in some patients) |

| Lip closure | 9 months* | 7 months | 4 months |

| Palatal closure | 36 months | 12 months | |

| Alveolar bone grafting | 8–11 years | 8–11 years | 8–11 years |

Note:

In summary, 32 patients from the Warsaw Cleft Center affiliated with IMC were treated with a one-stage repair of the cleft. Tennison–Randall technique was used for lip repair. One surgeon performed all operations. The mean age when photographs were taken was 10.9 years (SD = 1.4; range: 7.5–14). Gender proportion was: males 71.4%, females 28.6%.

A total of 26 children from the Prague Cleft Center affiliated with Faculty Hospital Royal Vineard underwent a two-stage repair. Millard technique was used for lip repair. Four surgeons performed all operations. The mean age of record taking was 9.9 years (SD = 1.7; range: 6.6–13.5). Gender proportion was: males 65%, females 35%.

A total of 17 children from the Bratislava Cleft Center affiliated with the Clinic of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Comenius University, were treated with a two-stage repair. Millard technique was used for lip repair. Four surgeons performed all operations. The mean age of record taking was 8.5 years (SD = 1.6; range: 4.9–11.5). Gender proportion was: males 75%, females 25%.

Methods

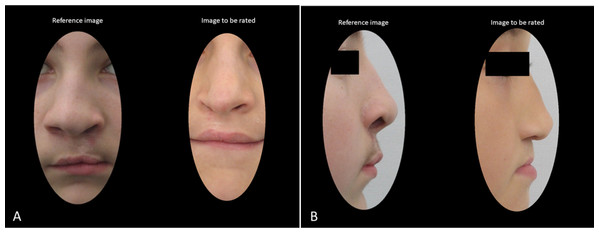

A 0–200 numeric scale with reference photographs, as recommended by Fudalej et al. (2017), was used. Thus, appearance of nasolabial area was rated on cropped frontal and profile images of the affected area with cropped reference photograph of a boy or girl present. The background of the slides was standardized. The images from Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava were loaded into PowerPoint in a random order for rating. Each slide comprised the frontal (or profile) view of one patient, a reference frontal (or profile) view photograph matched for sex, and a random number assigned (Fig. 1). Reference photographs selected by Fudalej et al. (2017) were used in the current study. The reference photograph had an a priori assigned score of 100. An image to be rated was compared with the reference photograph and scored above 100, if considered more esthetic than the reference, or below 100, if considered less esthetic than the reference.

Figure 1: An example of two slides presented during rating session of (A) cropped frontal and (B) cropped profile images with a reference photograph and an image to be rated.

Seventeen observers (7 professionals and 10 laypeople) rated all photographs. A professional rater was a doctor involved in treatment of CLP. Otherwise a rater was considered lay. All professional raters were orthodontists, pedodontists, and general dentists involved in treatment of patients with the cleft. Of them, 3 were males (age between 26 and 30 years) and 4 were females (age between 25 and 36 years). Professional raters were not involved in the treatment of study participants. Of 10 laypeople, 4 were males (age between 20 and 70 years) and 6 were females (age between 24 and 55 years). Four laypeople were dental technicians and six laypersons had no professional link to medical field. Before rating, a calibration exercise was carried out, so that the raters could familiarize themselves with the rating scale. There was no time limit for rating an image.

In order to assess intra-rater reliability, the 2nd rating session was organized after more than 2 weeks. During the 2nd session, 20 images were rated again.

Statistical analysis

Subjective assessment of esthetics of facial features produces considerable variation among raters, that is, individual scores can be quite different between raters. To reduce variability the scores for the professionals and the scores for laypeople can be averaged provided there is sufficient coherence among the observers. High coherence means that ranking of images is similar among observers despite variability of individuals scores. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients and intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to evaluate inter-rater coherence (agreement). If an inter-observer coherence was adequate, the mean scores of observers were used in the “Result” section.

Intra-rater agreement was assessed with ICCs, paired t-tests, and Bland–Altman plots (Bland & Altman, 1986). Comparisons among results achieved in 3 cleft centers were carried out with one-way ANOVA tests. Additionally, regression models with gender, group, age at lip repair, age when photograph was taken, and surgeon as independent variables and esthetic score as dependent variable. Four models were made, for esthetic score obtained on frontal and profile photograph and obtained by professionals and laypeople. Statistical significance was established for p < 0.05.

Results

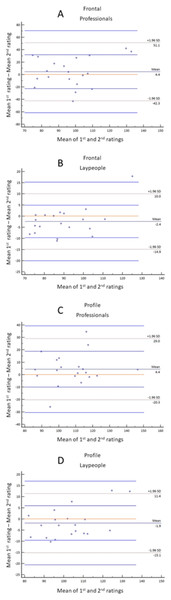

Reliability

Values of Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and ICCs (Table 2) indicated good and very good coherence for frontal and profile ratings among the professional raters and laypeople. The ICCs coefficients and Bland–Altman plots (Fig. 2) showed good intra-rater reliability. Thus, mean scores of the professional and lay raters could be presented in the “Result” section. Additionally, Table 3 shows that the mean results of 1st and 2nd ratings were comparable.

| Cronbach’s alpha | ICC average | ICC single | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI, LL | Coefficient | 95% CI, LL | Coefficient | 95% CI, LL | ||

| En face | Lay raters | 0.911 | 0.883 | 0.860 | 0.796 | 0.380 | 0.281 |

| Professionals | 0.883 | 0.845 | 0.824 | 0.737 | 0.401 | 0.286 | |

| Profile | Lay raters | 0.89 | 0.856 | 0.809 | 0.717 | 0.298 | 0.202 |

| Professionals | 0.827 | 0.771 | 0.733 | 0.611 | 0.282 | 0.183 | |

Note:

CI, confidence interval; LL, lower limit.

Figure 2: Bland–Altman plots for intra-rater agreement for frontal images rated by professionals (A) and laypeople (B) and profile images rated by professionals (C) and laypeople (D).

| 1st rating | 2nd rating | Difference | p value | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| En face | Laypeople | 88.48 | 15.89 | 90.92 | 12.78 | −2.44 | 0.102 | [−0.53 to 5.42] |

| Professionals | 99.1 | 22.27 | 94.67 | 17.68 | 4.43 | 0.416 | [−15.59 to 6.72] | |

| Profile | Laypeople | 102.04 | 15.57 | 103.9 | 12.38 | −1.86 | 0.234 | [−1.31 to 5.03] |

| Professionals | 109.88 | 16.27 | 105.52 | 14.87 | 4.36 | 0.138 | [−10.25 to 1.53] | |

| ICC average | ICC single | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI, LL | Coefficient | 95% CI, LL |

| 0.942 | 0.898 | 0.462 | 0.316 |

| 0.877 | 0.782 | 0.339 | 0.204 |

| 0.932 | 0.88 | 0.406 | 0.268 |

| 0.838 | 0.712 | 0.27 | 0.15 |

Note:

CI, confidence interval; LL, lower limit.

Treatment outcome

Table 4 demonstrates the results of evaluation of the esthetics of the nasolabial area in Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava groups. There were no inter-group differences for frontal and profile views (p > 0.1). The professional raters were less critical (i.e., assigned more favorable scores) than laypeople and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.005 and p < 0.001, for frontal and profile views, respectively; scores for Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava groups combined). Regression analysis (Table 5) demonstrates no effect of the gender, cleft center, age at lip repair, age when photographs were taken, and surgeon who repaired the cleft lip on the esthetic outcome.

| Warsaw (n = 32) | Prague (n = 26) | Bratislava (n = 17) | p value | paired differences |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| En face | Lay raters | 87.81 | 15.44 | 86.43 | 11.62 | 82.97 | 11.81 | 0.504 | – |

| Professionals | 93.62 | 20.73 | 97.12 | 15.07 | 89.35 | 19.18 | 0.422 | – | |

| Profile | Lay raters | 101.43 | 13.07 | 104.09 | 17.76 | 96.88 | 15.26 | 0.327 | – |

| Professionals | 112.90 | 16.46 | 112.34 | 16.06 | 114.78 | 17.66 | 0.890 | – | |

| Coefficient | SE | p value | 95% CI, LL | 95% CI, UL | p value of the model | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| En face, Professional raters | ||||||||

| gender (1, male; 2, female) | 3.46 | 5.42 | 0.526 | −7.38 | 14.29 | 0.886 | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| group (1, Warsaw; 2, Prague; 3, Bratislava) | −0.65 | 4.12 | 0.874 | −8.89 | 7.59 | |||

| age at lip repair | −2.68 | 7.40 | 0.719 | −17.49 | 12.13 | |||

| surgeon | 0.01 | 1.23 | 0.996 | −2.46 | 2.47 | |||

| age at photo assessment | 1.63 | 1.58 | 0.305 | −1.53 | 4.79 | |||

| Constans | 76.68 | 23.13 | 0.002 | 30.40 | 122.95 | |||

| En face, Laypeople | ||||||||

| gender (1, male; 2, female) | 2.53 | 3.61 | 0.486 | −4.70 | 9.76 | 0.731 | 0.05 | −0.04 |

| group (1, Warsaw; 2, Prague; 3, Bratislava) | −3.09 | 2.75 | 0.266 | −8.58 | 2.41 | |||

| age at lip repair | −2.03 | 4.94 | 0.682 | −11.91 | 7.85 | |||

| surgeon | 0.24 | 0.82 | 0.776 | −1.41 | 1.88 | |||

| age at photo assessment | 0.48 | 1.05 | 0.649 | −1.63 | 2.59 | |||

| Constans | 84.30 | 15.43 | 0.000 | 53.43 | 115.17 | |||

| Profile, Professional raters | ||||||||

| gender (1, male; 2, female) | 5.85 | 4.76 | 0.224 | −3.68 | 15.38 | 0.670 | 0.05 | −0.03 |

| group (1, Warsaw; 2, Prague; 3, Bratislava) | 1.99 | 3.62 | 0.584 | −5.25 | 9.24 | |||

| age at lip repair | −3.47 | 6.51 | 0.596 | −16.49 | 9.55 | |||

| surgeon | −1.34 | 1.08 | 0.221 | −3.51 | 0.83 | |||

| age at photo assessment | 0.8 | 1.39 | 0.567 | −1.98 | 3.57 | |||

| Constans | 101 | 20.34 | 0.000 | 60.31 | 141.69 | |||

| Profile, Laypeople | ||||||||

| gender (1, male; 2, female) | −2.52 | 4.45 | 0.573 | −11.42 | 6.38 | 0.733 | 0.05 | −0.04 |

| group (1, Warsaw; 2, Prague; 3, Bratislava) | −2.08 | 3.38 | 0.541 | −8.85 | 4.69 | |||

| age at lip repair | −0.3 | 6.08 | 0.961 | −12.47 | 11.87 | |||

| surgeon | 0.79 | 1.01 | 0.441 | −1.24 | 2.81 | |||

| age at photo assessment | 0.85 | 1.30 | 0.515 | −1.74 | 3.44 | |||

| Constans | 97.44 | 19 | 0.000 | 59.42 | 135.45 | |||

Discussion

In this part of the Slavcleft study we compared naolabial appearance in subjects treated with different protocols including surgical management of the cleft lip—centers from Warsaw and Prague used Tennison–Randall technique, while the center from Bratislava used Millard technique. Moreover, we requested 2 groups of raters—professionals and laypeople—to assess blindly frontal and profile photographs. We found that the esthetic outcome achieved in Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava was comparable (the H10 hypothesis was confirmed) despite significant differences in facial morphology (Urbanova et al., 2016) and dental arch relationship (Fudalej et al., 2019). This seeming inconsistency of the results was also found in the Eurocleft and Americleft studies—participating cleft centers differed considerably for morphological and occlusal outcomes while the nasolabial appearance of the patients treated with various therapeutical protocols was less diversified (Shaw et al., 2005; Russell et al., 2011). There could be several explanations for this phenomenon. First, facial morphology and dental arch relationship were directly affected by deficiency in the growth of hard tissues, whereas the effect of skeletal morphology on the appearance of the nasolabial area could have been modified by deformation of soft tissues of the nose and upper lip. Second, previous studies demonstrated that assessment of esthetics is associated with significant variability of the scores inflating standard deviation from the mean in evaluated groups (Bongaarts et al., 2008; Mercado et al., 2011). As a result, large samples are required to identify inter-group differences, possibly higher than these available in the current study. Finally, esthetics of the area affected by the cleft changes with age, particularly during the growth spurt. However, the subjects evaluated in this study were predominantly before the growth spurt. Thus, it is possible that the inter-group differences would be detectable at later age.

In this investigation we used a numeric scale with reference photographs to determine nasolabial esthetics. Our method was not the most commonly used in the research. Instead, most evaluations were carried out with the aid of a 5-point esthetic index developed for the Eurocleft study by Asher-McDade et al. (1991) or VAS scale without reference images (Sharma et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2016). Mosmuller et al. (2015) suggested that Asher-McDade esthetic index was superior to the other scoring systems. Nevertheless, the study by Fudalej et al. (2017) in which three methods of scoring nasolabial appearance—5-point esthetic index, 100 mm VAS, and 0 to 200 numerical scale with reference photographs—were directly compared, demonstrated that methods using reference images produced more reproducible results than did VAS or the esthetic index.

As mentioned before, 2 groups of raters—professionals and laypeople—judged nasolabial esthetics of all subjects. We requested persons involved in treatment of the orofacial clefts (professionals) and those without experience in therapy of the cleft deformity (laypeople) because previous studies showed the disagreement between scores assigned by professionals and laypeople—the first group was more, equal, or less critical in its judgements than the second group (Zhu, Jayaraman & Khambay, 2016). In the present study professional raters were significantly less critical than laypeople during evaluation of both types of images—frontal and profile ones. Our findings agree with results of Gkantidis et al. (2013) and Eichenberger et al. (2014) but disagree with Offert et al. (2013) and Foo et al. (2013). Although one can only speculate regarding the cause of this disagreement, it should be noted that despite the different level of criticism, both rater groups were in concordance that nasolabial appearance in patients treated in Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava was comparable.

It is widely accepted that operator’s skill is related with the outcome of surgery. In the CSAG study (Bearn et al., 2001) the surgeons performing primary lip and palate repair were split into high- and low-volume groups, using operations of five infants with UCLP per year as the cut-off point. According to Bearn et al. (2001) five cases with UCLP is equivalent to an annual caseload of 15 new referrals for primary surgery of all cleft types. The findings of CSAG demonstrated that 5-year-olds operated by high-volume surgeons had better speech and nasal appearance. The effect of surgeon on esthetic outcome, however, disappeared in 12-year-olds. In this investigation, one surgeon with >10 years’ experience in cleft surgery and large annual workload (>50 primary cleft surgeries per year) operated all subjects in Warsaw, while several surgeons were involved in operations of patients in Prague and Bratislava. Therefore, it was particularly interesting to explore the relationship between surgeon’s experience and esthetics outcome. We found no effect of surgeon on the nasolabial appearance as demonstrated by regression models. Thus, our results are in agreement with findings of Bearn et al. (2001).

Initially, we planned to explore the relationship between esthetic and morphological outcomes, that is, between nasolabial appearance and morphology of the face. It was logical to assume that deficient growth of the face could lead to impaired appearance. Unfortunately, we were faced with a common problem in the cleft research, namely, inconsistency of record taking. The dates when lateral cephalograms, diagnostic models, and photographs were made significantly differed for so many subjects that it was impossible to carry out this assessment. Moreover, basal (worm’s-eye) view of the nose—helpful in evaluation of nasal symmetry—was available only for minority of participants and was not therefore included in the study. This study has also other limitations such as relatively small sample size and assessment of non-consecutive patients in Prague and Bratislava groups. Moreover, retrospective study design, commonly met in the cleft research, is associated with higher risk of bias in comparison to prospective studies.

In summary of the whole project, the results of the Slavcleft were similar to the outcomes of the Eurocleft and Americleft—centers did not perform equally well, although the differences were not dramatic. Better performance was not universal, that is, it did not concern all outcomes, but it was limited to morphological (cephalometric and occlusal) ones. Nasolabial appearance was comparable in all groups and this fact can matter much because, after all, acceptable nasolabial esthetics is likely more important for a patient than skeletal or dental morphology. In this short round-up, we would also like to express a certain dissatisfaction because the problems such as inability to collect consecutively operated patients, inconsistency of record taking, or missing precise information on secondary surgeries weakened our conclusions. Despite, it was worth carrying out this inter-center comparison because it allowed Warsaw, Prague, and Bratislava cleft centers to view ones’ results against a background of other participants.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study we conclude that none of the surgical protocols showed superiority to produce good nasolabial appearance.