The 67th Symposium on Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy (SVPCA) 2022 (rearranged from the cancelled 2020 meeting) was organised by the Fossil Reptile Research Group at The Natural History Museum in London in September. We welcomed around 160 professional and amateur palaeontologists, biologists, and anatomists from around the world to three days of talks and posters on a variety of interesting topics. Despite the best efforts of COVID-19, the meeting was a great success, with some fascinating new research on display. Through the annual charity auction, we were able to raise over £2,500 to enable those with no financial support to attend future meetings. Highlights included talks on British fossils, global trends in biodiversity, and the evolution of mammals.

Joseph Bonsor, Host Committee Member

*****

James Rule Postdoctoral Researcher, Natural History Museum London, UK.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your research interests?

I am a vertebrate palaeontologist/evolutionary biologists who studies the evolution of aquatic tetrapods. I mostly focus on the evolution of pinnipeds, having completed a PhD looking at the taxonomy, evolution, and biogeography of southern true seals. My current work focuses on the evolution of their sensory biology (particularly their auditory biology). I also occasionally study the evolution of terrestrial tetrapods, particularly marsupials, and occasionally Dinosaurs such as Triceratops.

What first interested you in this field of research?

I have always been interested in palaeontology, ever since I was very young. My more recent interests in pinniped auditory biology began when I was studying my PhD, when I learnt how seal ears “worked”. My current postdoctoral research originated from some preliminary data collected during my PhD, for a project that was excluded from my PhD due to the global pandemic.

What sort of techniques do you use in your research?

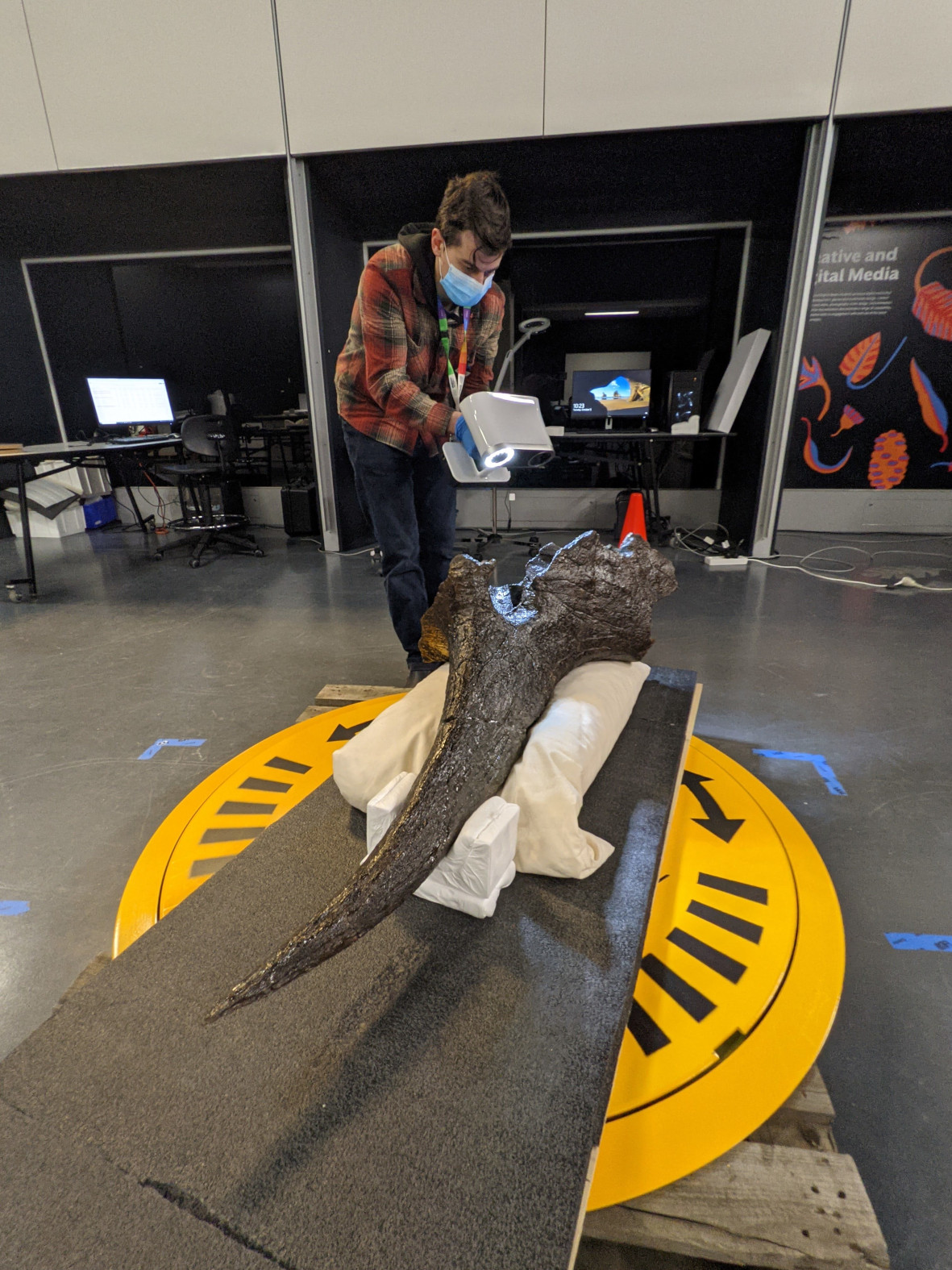

I often use CT and surface scanning to examine the sensory morphology of animals. I also do a lot of taxonomic and phylogenetic based work, including Bayesian phylogenetic inference and phylogenetic comparative methods, to investigate the biology and biogeography of animals.

I often use CT and surface scanning to examine the sensory morphology of animals. I also do a lot of taxonomic and phylogenetic based work, including Bayesian phylogenetic inference and phylogenetic comparative methods, to investigate the biology and biogeography of animals.

Can you briefly explain the research you presented at SVPCA 2022?

Seals have an ability unique among mammals: the ability to hear in-air and underwater. Amphibious hearing is meant to be physically impossible due to the mammalian ears reliance on air; but seals overcome this problem by matching the density of water using a cavernous sinus in their ear. My research used CT scanning to look at the extent of this sinus in a Leopard seal’s ear. By comparing the osteology of extant and fossil taxa, I investigated any osteological correlates that could be used to explore the evolution of underwater hearing in seals.

How will you continue to build on this research?

I have just started a Marie Curie postdoctoral research project to investigate the evolution of underwater hearing in seals. During this project I plan to microCT scan extant and fossil pinniped specimens, and supplement that data with dissections of wet specimens. I will also implement phylogenetic comparative methods to investigate how pinniped hearing evolved through time.

Credit: Peter Trusler

Zixiao Yang Postdoctoral Researcher, University College Cork, Ireland.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your research interests?

I have always been fascinated by how ancient creatures have survived millions of years and come to tell their very own life stories that were written in not just bones but also delicate flesh and feathers. Therefore I consider myself very lucky to be able to study the Mesozoic Yanliao and Jehol biotas in China, which have yielded thousands of exquisite fossils of early birds, feathered dinosaurs, pterosaurs and early mammals, among others. Particularly I am interested in the possible mechanisms responsible for their famous exceptional soft-tissue preservation (e.g. feathers, hair, skin, gill arches, eyespots, etc.), and the potentially rich biological and evolutionary information enclosed within the soft-tissue remains. Currently, my colleagues and I are exploring the question of how feathers have evolved through time by looking at some of the fantastic fossils from these biotas.

What first interested you in this field of research?

I was born in Nanyang (Henan Province, China), a small town but a popular nesting site for dinosaurs – the incredibly abundant dinosaur egg fossils discovered in this region have made it one of the richest dinosaur egg sites in the world. So I was no stranger to dinosaur skeletons and egg shells when growing up. After I got into college, however, I was really shocked to learn that dinosaurs and other ancient creatures could be preserved in more than just bones (although I was disappointed with the reality that Jurassic Park probably won’t happen). Since then, studying exceptionally preserved fossils has been my one and only fascination.

Can you briefly explain the research you presented at SVPCA 2022?

DThe work I presented at SVPCA 2022 was a close collaboration between the Maria McNamara Research Group at University College Cork and Prof. Baoyu Jiang from Nanjing University. The aim of the study was to better understand the skin modifications in the evolutionary transition from scale to feathers. We investigated a new specimen of Psittacosaurus (Jehol Biota), a non-avian dinosaur known to preserve feathers on the tail and scales in other body regions. The key question was whether the feather-related skin modifications were confined to feathered regions, such that the non-feathered regions were essentially reptile-style scaled skin; or alternatively, had the non-feathered regions also been modified? By comparing the fossilised skin ultrastructure with that of modern crocodiles and birds, we found that Psittacosaurus probably retained the primitive condition of its scaled ancestors in non-feathered regions. Such highly localized skin modifications suggest spatial partitioning of gene expression, which is also known in the development of modern feathers.

What are your next steps?

Aside from the amazing anatomical details preserved in this new Psittacosaurus specimen, the taphonomy of this specimen is also fascinating. The fossil skin is replicated in silica; this is, to our knowledge, the first known example of cellular-level preservation of vertebrate soft tissue via silicification. So we are hoping to learn more about the potential mechanisms that led to such amazing preservation. On the topic of scale-feather transition, we are also looking at other dinosaurs in order to ultimately trace how skin structures have co-evolved with feathers.