The 2021 annual congress of the Association Paléontologique Française (APF) brought together more than forty researchers, postdoctoral academics, PhD students and amateur palaeontologists to the French medieval city of Troyes (Champagne), between August 30th and September 3rd. The congress was organized by the Association Géologique Auboise (AGA), who celebrated their 50 year anniversary during the meeting. Three days were devoted to the presentation of oral communications and posters; the fourth was dedicated to the field trip: discovering the different regions around Troyes and their geological composition from the Upper Jurassic to the Lower Cretaceous; the day ended with a champagne tasting at a local winemaker!

The winner of this years PeerJ Award is Bastien Mennecart from the Natural History Museum in Basel, Switzerland, for his excellent presentation on the evolution of the inner ear of ruminant mammals over 35 million years.

Nathalie Bardet (organiser)

*****

Bastien Mennecart Associate researcher at the Natural History Museum in Basel.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your research interests?

I have been studying in France at the Universities of Orléans, Poitiers, and Montpellier. After defending my PhD in Switzerland, I received postdoc grants to work in Paris, Munich, Vienna, and Basel museums.

I am a specialist in early ruminant evolution. This is an interesting group of highly diversified mammals, with more than 200 living species. Everybody knows ruminants bearing cranial appendages like the giraffes, deer, antelopes, goat … but fewer know that 10% of the extant ruminant species – and all the ruminants earlier than 18 millions years ago – are sabre-toothed. My work is basically to do taxonomy, biostratigraphy, and paleoecology of these early ruminants to better understand the various processes involved in their diversification. I also work with CT-data, mostly on the ear region, in collaboration with colleagues from all around the world. This is a pretty interesting organ being at the origin of the balance and audition but also being very conservative in shape.

What first interested you in this field of research?

What I really love in science, generally speaking, is to answer questions and lots of questions remain about this group of mammal. When and where is the temporal and special origin of their success, and which processes were involved in it? What are the relationships between the different taxonomic families, including to those still living? What is the origin of their fancy cranial appendages? These research topics lead me to work in the USA, Mongolia and China, and to clarify the connection between Asia and Europe during the Cenozoic, describing new mammalian events (Bachitherium dispersal event and Microbunodon event) and new mammal species. These collaborations are the base of a scientific work, working together to go further. We have, for example, just described with my colleagues the oldest modern ruminant and a new species of ruminant with proto-horn that may shed a light on the origin of the bovid horns.

You won the Best Early Career Researcher Presentation award at APF 2021, can you briefly explain the research you presented?

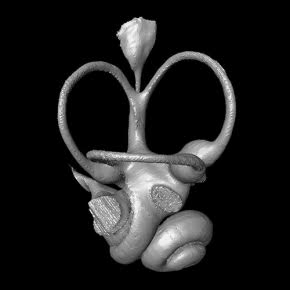

My presentation was entitled “35 million years of major events seen through the inner ear of ruminants”. This presentation was a synthesis of seven years of research on the bony labyrinth (the bony capsule protecting the inner ear). Three hundred bony labyrinths from 200 extant and extinct ruminant species have been studied. We have determined that the bony labyrinth is a structure that fully ossifies early during the foetus stages (at the mid-gestation), that is specific, and sheds light on the phylogeny of the studied group. However, using large datasets, we could not find that the shape of this organ could predict the head posture or the environment (excepted in extreme cases), contrary to what it is often published. The observed shape differences and trends show that the evolutionary rates of this structure reflects the broad evolution at the family level. Indeed, the variation of evolutionary rates of the bony labyrinth morphology through time correlates with the evolutionary potential of the various clades.

I would like to give thanks to my presentation co-authors, Loïc Costeur and Laura Dziomber, and to numerous collaborators around the world.

How will you continue to build on this research?

Now that, thanks to the bony labyrinth, we have a better picture of the broad ruminant story, it will be interesting to focus on some intriguing stories like the insular evolution and the domestication. Moreover, all these 3D reconstructed bony labyrinths are new to science and should be published to show the specific morphology and shape diversity of this structure. I would like also to continue to go on the field, finding fossils and describing them, and to continue having fun and enjoying my job!