This week we published the study RNA expression and disease tolerance are associated with a “keystone mutation” in the ochre sea star Pisaster ochraceus by V. Katelyn Chandler and John P. Wares. Using RNA sequencing methods, the researchers identified a number of differences between two variants of the same sea star species. We interviewed John Wares about the findings and how the identified DNA mutation may affect the species’ tolerance to stress, disease, and environmental change. We were deeply saddened to hear of the passing of co-author Katelyn Chandler who was part of the student team at the University of Georgia undertaking this research.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

I study cryptic variation – what can’t easily be seen by the eye, but which may be really important to understand how connected populations of an organism are, or how they are responding to distinct environments. Most of my work is on marine organisms, and I identify cryptic diversity within these species using a variety of DNA markers. This helps us understand how ocean currents move offspring around, and how cryptic diversity may be associated with particular environments or habitats. In some cases this even allows us to diagnose new species or interactions.

Can you briefly explain the research you published in PeerJ?

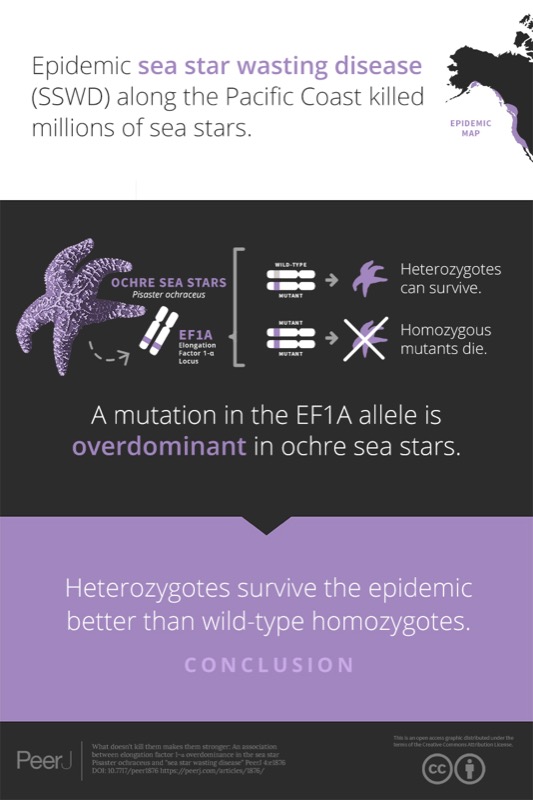

We wanted to examine two variants of the sea star Pisaster ochraceus, which are distinguished by whether they carry a copy of a single particular DNA mutation or not. This mutation is associated with some form of tolerance to a devastating disease (Wares & Schiebelhut 2016, PeerJ). So, we used RNA sequencing to understand what genes might be more abundantly expressed in one of the two types than the other. It turns out that the two variants are not just distinguishable by whether they carry a mutant allele; they appear to regulate a large number of genes differently, and this looks like it affects an individual’s tolerance for heat stress.

Do you have any anecdotes about this research?

When I think about this research, I mostly think of the students who were involved – some at the Friday Harbor Laboratories, where the behavioral work and tissue sampling was done as part of a class experiment; and the students who helped me genotype, sequence the RNA, and analyze the data back at the University of Georgia. They have all been phenomenal to work with and took the work really seriously – but seemed to have fun at the same time. In particular, I will always remember my co-author Katelyn Chandler who was brilliant and energetic and inquisitive but unfortunately passed away only weeks after we submitted this manuscript.

What kinds of lessons do you hope the public takes away from the research?

This sea star is perhaps one of the best-known intertidal invertebrates, largely thanks to Bob Paine and his many contributions to community ecology starting over 50 years ago. When an organism has been intensely studied for so long, it is easy to assume that we know all that we need to know – but I think we are entering a whole new era of understanding how individuals vary in tolerance to stress, disease, and environmental change, not just in these gorgeous echinoderms but in all species – even humans.

How did you first hear about PeerJ, and what persuaded you to submit to us?

I can’t remember how I first heard about PeerJ, but I was intrigued by the publishing model. I appreciate that the work can stand on its own merits, not just on decisions that editors make based on a handful of ad hoc reviews and concerns about page limitations in their journal. Plus I knew a lot of really good colleagues who had joined the editorial board, so I took the new journal and format seriously.

How would you describe your experience of our submission/review process?

Incredibly professional. Not only has the peer review process typically been quick, but one of my papers I actually got an apology from the editor when the handling time was longer than usual. For many of us, getting our work out quickly aids in showcasing our work, competing for funding, and simply being relieved to have something completed. Some society journals have led to delays of greater than a year between the time of submission and the time of publication for my work. Either way, the peer review process results in great improvements to my work, and I think publishing the reviews can be really useful to increase the transparency of science as well.

Would you submit again, and would you recommend that your colleagues submit?

Absolutely. This is my 7th PeerJ paper and I’ve always been pleased with the process and the final product. PeerJ really helps me reach a larger audience with their promotional skills, both in terms of social media as well as ‘graphical abstracts’ for some papers (Wares & Schiebelhut 2016). I also consider myself a biologist with pretty diverse interests so I appreciate putting my work in a journal that covers so many facets of the biological sciences.

Anything else you would like to add?

Thanks for this opportunity!