Celebrating Open Access Week 2014 affords an opportunity to study and promote all aspects of ‘Open.’ One of the things that we are most proud of at PeerJ is the feature for reviewers to name themselves, and for authors to optionally publish the back-and-forth dialogue of their manuscript’s review history.

Otherwise known as ‘open review,’ this isn’t entirely unique to PeerJ, but the specific way that it has been implemented might be at this point. While some journals require the full history to be published and reviewers to be named (i.e. it is not optional), most journals provide no option to do so at all. PeerJ is somewhat unique in that it is all optional – the author and the reviewer have a choice. At this moment in time, where changes are happening everywhere in academia, we think this is a good transitional path that is working for our audience – your mileage may vary of course! This post is an attempt to shed some light on why we introduced optional open review and what the early take up looks like so far.

Life is harsh, but it’s better than the alternative

Human beings are a capricious bunch. On the one hand we tend to think that the grass is greener on the other side, whilst simultaneously we quite enjoy maintaining the status quo. Is this really cognitive dissonance, or is there some logic to it? Like many other long established traditions and bureaucracies we love to complain ad nauseam that the current system of peer review is rife with problems, is broken, is biased and is holding us back. At the same time we don’t like change because there can be benefits to the current system. In other words, the system is terrible – but it is the best one we’ve got and the alternative may be worse!

Some of the problems we rail against include: reviewer bias, difficulties in blinding authors/reviewers, opaqueness or subjectiveness of reviews, invitation for undue criticism with blind reviews, and even a question of whether any review was done at all! That last item in particular has become a talking point for many opposed to Open Access. The recent ‘Bohannon sting,’ which solely targeted Open Access journals, didn’t help the OA cause much – let’s just admit that. (And the title of this blog post is a tongue-in-cheek of Bohannon’s article title in case you didn’t catch that) Yes, it was unfair to test the review practices of journals already known to be bad apples by the academic community, but it also highlighted the fact that we have loads of outreach to do to tell the good stories within Open Access. There are many good apples in Open Access. The silver lining to the Bohannon report was that known brands like PLOS ONE, which PeerJ shares an editorial model with, were excellent in spotting fake or poor manuscripts.

In truth, the issues with peer review listed above can and do happen whether the journal is Open Access or a traditional subscription journal. The quality of peer review is independant of the price to read an article. Indeed, there are plenty of problems with peer review happening within subscription journals that predate Open Access, but focusing on the mode of scholarly communication is a distraction to the underlying cause. And we must not throw the baby out with the bathwater just because there are problems with peer review. Peer review has its benefits, as do experiments testing a post-publication peer review model. Post-publication review is another conversation though and not the focus of this post.

Discovering the middle ground

We often forget that there is usually a third choice in any debate – a middle ground. We don’t necessarily need to throw peer review out the window and start over, and we don’t need to stick with exactly what we have either. ‘Open Review’ is a third option. There doesn’t seem to be a widely accepted definition of open review just yet, but at PeerJ when we use the phrase ‘open review’ we’re speaking of two things:

- Reviewers ‘sign’ their reports (making their names known).

- Authors publish the review history alongside the accepted publication.

Note: Open review can also refer to post-publication review, where the manuscript is first published and then reviews take place publicly. However, as stated previously we do not practice this at PeerJ, although authors can choose to ‘preprint’ a manuscript before submitting for formal peer review to take place behind the scenes. (Further reading on the difference between preprints and peer-review).

At PeerJ open review is optional and up to the reviewer and author to decide. There do exist a few radical journals that make this mandatory and there is certainly a niche for that. We chose a transitional approach to open review and offer the incentive of DOIs for the reviews and recognition elsewhere. Open review is a rapidly developing concept that is gaining acceptance within the academic community. Through anecdote, data analysis, personal communication, and public broadcasts we’ve been seeing a growing appreciation for PeerJ articles that choose open reviews.

The benefits of those choosing open review that we’ve seen thus far have included:

- More civil discussion behind the scenes

- A perceived, if not real, reduction in reviewer bias

- More thorough back-and-forth dialogue

- It’s helped answer several reader questions of 1) why research was done in the first place and 2) what quality of review was behind the decision to accept

- Countless mentions of the review history being used as a pedagogy tool in the classroom and as case studies for current referees to use as guides.

- Review histories have helped incoming manuscripts from both new and seasoned researchers. They have a study guide of what constitutes an acceptable manuscript.

- Authors are less worried about revealing themselves within the body of their manuscripts, and likewise reviewers within their review text.

- Authors want to publish in journals with constructive criticism and have been encouraged to submit simply because they’ve seen the quality of peer review in their colleague’s publications.

The biggest benefit is perhaps that the entire research lifecycle from hypothesis > experiment > publication is being improved through the choice of open review. At PeerJ we launched with optional open review thinking it would help answer the quality myth about Open Access and being a new journal. We’re now marvelling that open review is having a direct impact on the research itself.

How open are academics?

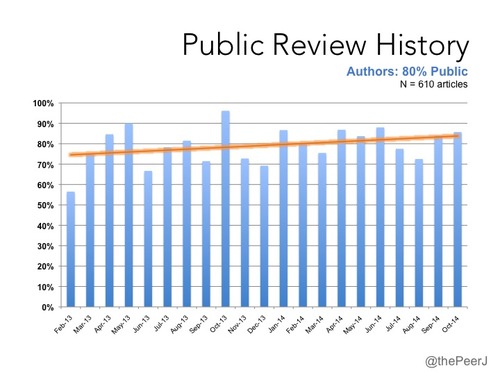

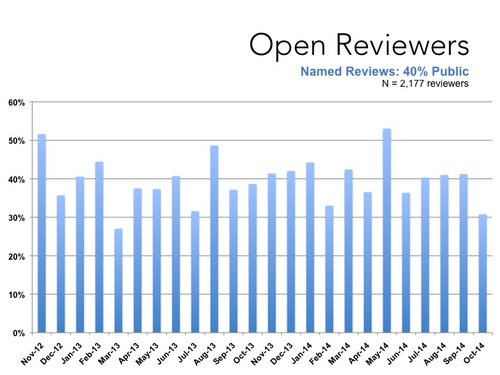

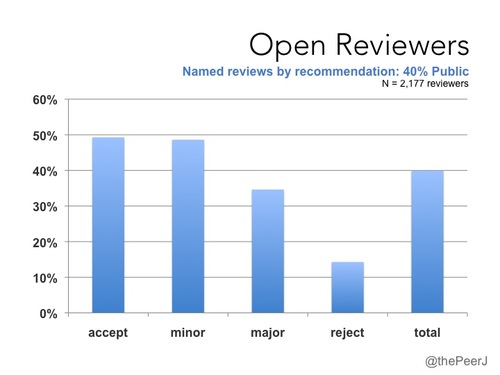

What’s the use in talking about optional open review and not showing what it actually looks like?! So, let’s dig into some of the data at PeerJ. Since signing reviews and making the review history available are optional we are able to do a study on how open academics tends to be. As of October 13th, 2014 when we checked this data we had published 610 peer-reviewed articles (first article Feb 2013) with ~2,400 authors and had performed 2,177 reviews in 94 subject areas. That reviewer number includes both accepted and rejected manuscripts.

Some key observations:

- 80% of authors choose to publish the full peer review history – and that percentage is growing.

- 40% of reviewers choose to sign their reviews (i.e. make their name known to the author).

- The most open subjects tend to be about science education and have a computational basis.

- The most published subject areas tend to have more signed reviews. In contrast, there is little correlation between the most published subject areas and authors making the review history public. Put another way, the more open subject areas are not necessarily the same depending on the role of author versus reviewer.

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, fewer reviewers recommending a ‘reject’ choose to sign their reports.

- We don’t yet have segmentation for seniority of reviewers and authors and how that might correlate with the decision to be more or less open.

When PeerJ launched we could not have anticipated what fraction of reviewers and authors would go the open route if given the choice. It could have gone either direction. The data below suggest that the life science and medical communities might be more ready for ‘open’ than common belief holds. Kudos must go of course to these early adopters of a more open process and for recognizing the immediate and long-term benefits that open review brings. Still, we welcome those who are not quite ready for the open review path, as we understand some situations may prevent taking it up. We’re progressing together as an academic community and we think they are steps in the right direction. We wish you a very happy Open Access Week.

Captions:

Figure 1 (below): Percentage of PeerJ authors choosing to make the manuscript review history public since the journal launch.

Figure 2 (below): Percentage of articles by subject area choosing to publish the review history.

Figure 3 (below): Percentage of reviewers opting to sign their reviews since PeerJ started accepting submissions (Nov 2012).

Figure 4 (below): Percentage of articles by subject area with signed reviews

Figure 5 (above): Percentage of signed reviews by recommendation.