A secure cross-domain federated learning scheme based on blockchain fair payment

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Ankit Vishnoi

- Subject Areas

- Cryptography, Security and Privacy, Blockchain

- Keywords

- Information security, Federated learning, Blockchain

- Copyright

- © 2026 Li et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. A secure cross-domain federated learning scheme based on blockchain fair payment. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3589 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3589

Abstract

Background

Cross-domain federated learning is an innovative machine learning paradigm that allows data owners from different domains to collaboratively train a shared model while preserving data privacy. However, cross-domain federated learning also faces numerous challenges, such as data and system heterogeneity, client reputation management, and potential threats from malicious attackers.

Methods

To address these issues, this article proposes a secure cross-domain federated learning scheme based on blockchain fair payment. The proposed scheme effectively evaluates and updates the reputation of each client through a reputation management mechanism and allocates fair rewards based on their contributions. Additionally, the scheme employs advanced cryptographic technologies such as blockchain and zero-knowledge proofs to ensure the security and fairness of data and transactions. A series of experiments are conducted to evaluate the performance and fairness of the proposed scheme on multiple datasets and models, and comparisons are conducted with other mainstream federated learning algorithms. MNIST Dataset is available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hojjatk/mnist-dataset. Fashion-MNIST Dataset is available at https://github.com/zalandoresearch/fashion-mnist. CIFAR-10 Dataset is available at https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html.

Results

The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed scheme ensures the performance of federated learning while also maintaining its fairness and security. Specifically, the method achieves a test accuracy of 97% on the MNIST dataset, outperforming Federated Averaging (FedAvg) (95%) and Stochastic Controlled Averaging for Federated Learning (SCAFFOLD) (96%). On the FEMNIST dataset, it attains 89% accuracy. In terms of convergence speed, the proposed optimization-based reputation method converges in 26 rounds, which is faster than baseline methods (28–32 rounds). Under data tampering attacks (50-client scenario), the accuracy drop is less than 3%, showing strong robustness. For fairness, the trust difference and reward difference are reduced to 0.10 and 0.08, respectively. The proposed scheme significantly improves the accuracy, convergence speed, robustness, and fairness of cross-domain federated learning, advancing its practical deployment in real-world scenarios. The experimental data is available at: https://zenodo.org/records/15210778.

Introduction

With the proliferation of the Internet and mobile devices, the speed and scale of data generation have continuously increased, providing great opportunities and challenges for the development of artificial intelligence and machine learning. However, due to the increasing challenges of data fragmentation (Castro-Medina, Rodríguez-Mazahua & Abud-Figueroa, 2019), privacy and security issues (Abba Ari et al., 2024), and the complexity of cross-domain learning (Zhu, 2025), traditional centralized machine learning methods are inefficient and impractical in fully utilizing these distributed data resources. To address these challenges, federated learning has emerged as a novel distributed machine learning paradigm, enabling multiple data owners to collaboratively train a unified model without sharing their data (McMahan et al., 2017).

Although federated learning effectively addresses data privacy and fragmentation issues, it still faces numerous challenges, including system heterogeneity (Yuan et al., 2024), client dynamism (Lin et al., 2024), model scalability (Peebles & Xie, 2023), and the design of incentive mechanisms (Hu et al., 2024). Particularly in the context of cross-domain federated learning, data distribution differences and the lack of trust relationships make the solutions even more complex and challenging (Borger et al., 2022). Cross-domain federated learning needs to ensure collaborative training across multiple data owners and datasets while safeguarding the privacy and security of all parties’ data (Parekh et al., 2021).

To address these challenges, this article proposes a blockchain-based secure cross-domain federated learning solution. The solution utilizes the trusted management mechanism of blockchain to dynamically update client reputation values and ensure fair and reasonable benefit distribution. This article combines blockchain and zero-knowledge proof technologies to enhance the security and fairness of cross-domain federated learning.

The main contributions of this article are as follows:

We propose a blockchain-based secure cross-domain federated learning solution, combining reputation management, zero-knowledge proof, and other techniques to solve the privacy, security, and fairness issues in cross-domain federated learning.

We design a comprehensive reputation management mechanism, including reputation calculation, sharing, integration, and optimization tasks, considering multiple attributes of client performance in different domains, and evaluate the privacy and security of the proposed reputation management solution.

We conduct extensive experiments on multiple data sets and models to evaluate the performance and fairness of the proposed solution, and compare it with mainstream federated learning algorithms to verify the practicality and effectiveness of the proposed cross-domain federated learning solution.

Related work

This section reviews the research progress related to our work, primarily including the following aspects: federated learning, reputation management, blockchain, and zero-knowledge proofs.

Federated learning, as a paradigm of distributed machine learning, was first proposed by McMahan et al. (2017). Since then, Brisimi et al. (2018) demonstrated the effectiveness of federated learning in intelligent healthcare models. Xu & Lyu (2020) analyzed the challenges and opportunities of federated learning, proposing an adaptive federated learning method. Klindt et al. (2020) explored the security and privacy issues in federated learning and proposed solutions. Xiong et al. (2022) provided a comprehensive review of federated learning, summarizing the main challenges and directions in this field. Wei et al. (2020) introduced optimization methods for security in federated learning, laying a foundation for subsequent research. Park et al. (2021) proposed a new parallel training algorithm for federated learning, significantly improving training speed. Tang, Chen & Zhang (2019) published a comprehensive review on the progress of federated learning, summarizing the main challenges and opportunities in the field. Cross-domain federated learning, as a special scenario of federated learning, was first proposed by Parekh et al. (2021). Borger et al. (2022) conducted an in-depth analysis of the complexity and challenges of cross-domain federated learning, addressing issues such as data distribution differences and lack of trust relationships. However, existing research primarily focuses on data synchronization and distribution differences, neglecting how to resolve conflicts of interest and fairness issues between different clients while ensuring privacy.

Blockchain technology has also been widely used in federated learning to enhance data security. Li et al. (2021) explored how to enhance data security based on blockchain technology. Mahmood & Jusas (2021) introduced a blockchain-based federated learning architecture. Ali, Karimipour & Tariq (2021) focused on the integration of blockchain with federated learning to address privacy issues. Ayaz et al. (2022) proposed a blockchain-based federated learning scheme to ensure the security of communication paths. Compared to traditional centralized methods, blockchain offers a decentralized, trusted mechanism. However, a comprehensive framework that addresses data privacy, security, trust, and fairness issues in cross-domain federated learning is still lacking.

Reputation management is critical in federated learning. Al-Maslamani et al. (2022) proposed a reputation-based trust management model for distributed systems. Chen, Christensen & Ma (2023) introduced a dynamic reputation evaluation method to enhance the robustness and security of federated learning. Shen et al. (2022) studied the impact of reputation management on the privacy and security of federated learning. Gu et al. (2022) introduced an adaptive reputation evaluation model to ensure the robustness and security of federated learning. Most recently, Fan & Zhou (2023) proposed a reputation-based federated learning model to ensure data security and privacy. While several works have introduced dynamic reputation evaluation methods, these approaches mainly focus on the same-domain federated learning scenario and do not address how to dynamically update client reputations and ensure fairness in cross-domain collaboration.

Although numerous studies have attempted to solve trust, privacy, and security issues in cross-domain federated learning, most focus on optimizing a single aspect and lack a comprehensive solution. Specifically, how to balance the interests of all parties and ensure system fairness in a cross-domain environment remains an unresolved challenge. This article proposes a comprehensive solution that combines blockchain and zero-knowledge proofs, effectively addressing trust and privacy issues in cross-domain learning. It also dynamically adjusts client reputation values and ensures fair distribution of benefits in cross-domain federated learning.

Preliminary knowledge

To construct a secure cross-domain federated learning scheme based on blockchain fair payment, this section will detail the relevant preliminary knowledge. This includes the basic principles and practice of federated learning, the core structure and functionality of blockchain technology, and the concept and implementation of blockchain fair payment, as well as the mathematical representation of related vectors (DR vector) and zero-knowledge proofs.

Blockchain fair payment

In blockchain fair payment, all-or-nothing proof protocols and Bitcoin’s timed commitment schemes play crucial roles.

- 1.

All-or-Nothing Proof Protocols: This is a protocol to ensure the integrity of transactions. Suppose there is a set of data , the all-or-nothing proof protocol can verify the integrity of the data through the following cryptographic operations: using encryption to encrypt each element of the data set; i.e., , . The completeness is verified by computing the hash value of the concatenated encrypted data and comparing it with the pre-stored hash value: (1)

- 2.

Bitcoin Timed Commitment Schemes: This is a type of cryptographic protocol based on blockchain, where a proposer S locks certain information (such as a secret) until specific conditions (such as a specified time) are met. The scheme involves three main phases:

• Commit Phase : The proposer S makes a commitment and deposits a guarantee amount , used to ensure S will reveal the commitment at a specified time . Before , S must keep the commitment secret. Here, CS refers to the “Commitment Scheme,” a cryptographic protocol used to lock the information until the specified condition is met.

• Open Phase : If S reveals the secret before , S retrieves the guarantee amount .

• Fine Phase : If S fails to reveal the secret before , the guarantee amount is transferred to C. This phase ensures the penalty is executed only if the open phase is not completed on time.

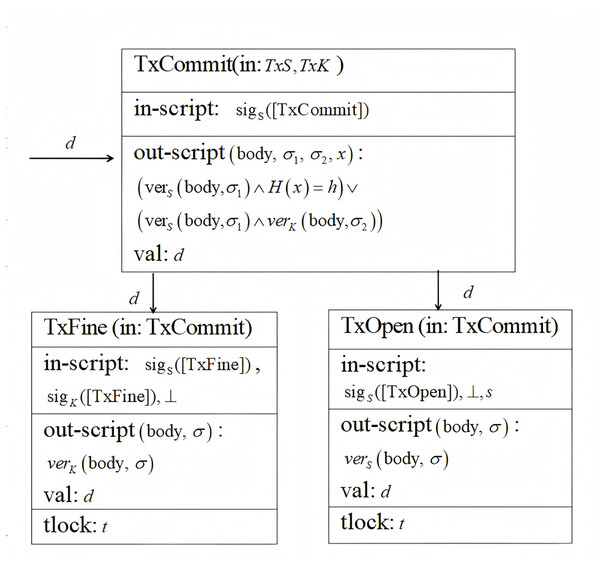

An example structure: is used for the commit phase, including input, output script, and the guarantee amount . is used for the open phase, including input, output script, and the returned guarantee amount . is used for the fine phase, and if S fails to reveal, is transferred, allowing C to execute the transaction.

Directed relationship vector (DR vector)

A directed relationship vector is a mathematical structure used to represent directed relationships between objects. In distributed learning and federated learning, the DR vector is used to represent the mutual relationships and weight distribution between clients. By adjusting the weights, the balance between global objectives and local objectives can be achieved. The directed relationship vector is an N-dimensional vector, where N is the total number of clients. Each element of the vector represents the weight of client towards client . It can be represented as:

(2)

The weight can be allocated in various ways, such as based on similarity, credibility, or other criteria. A common weight allocation formula is:

(3) where is a similarity function, which can be cosine similarity or Euclidean distance.

Cryptographic knowledge

Zero-knowledge proof (ZKP)

A zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) allows the prover to convince the verifier that a statement P is true without revealing any specific details. Zero-knowledge succinct non-interactive argument of knowledge (ZK-SNARK) is a special type of ZKP, enabling one party to prove knowledge of a secret value satisfying a condition without revealing the value.

The basic workflow involves three phases:

- 1.

Setup Phase: Public parameters and key pairs are generated: (4) where is the proving key, is the verifying key, and is the security parameter.

- 2.

Proof Generation: The prover uses public parameters and a secret value to generate a proof: (5) where is the public input and is the secret witness. The prover may also use a random value to commit to the secret, ensuring the proof remains valid without revealing the secret. and simulate a random challenge-response interaction between the prover and verifier, ensuring the proof’s soundness and zero-knowledge properties.

- 3.

Proof Verification: The verifier uses the public parameters and the proof to verify the statement: (6)

Secret sharing

Secret sharing is a method that allows a secret to be divided into multiple parts so that only a specific number of parts can be used to reconstruct the original secret. Shamir’s threshold secret sharing scheme is a common solution, where represents the minimum number of shares needed to reconstruct the secret, and represents the total number of shares. This scheme ensures that the secret can be reconstructed only when at least shares are available.

Secret Establishment Process: Choose a polynomial of degree :

(7) where is the secret to be protected, and are randomly chosen coefficients. Then generate the shares by selecting different points and computing:

(8)

These points are distributed to different participants.

Secret Reconstruction Process: Collect shares and use Lagrange interpolation to reconstruct the secret:

(9)

Cross-domain federated learning scheme

To explore the practical application of a secure cross-domain federated learning scheme based on blockchain fair payment, this section provides a detailed explanation of the proposed system model, the federated learning workflow, and privacy protection in personalized cross-domain model training. The objective is to construct a cross-domain federated learning scheme that ensures fair transactions and user privacy protection.

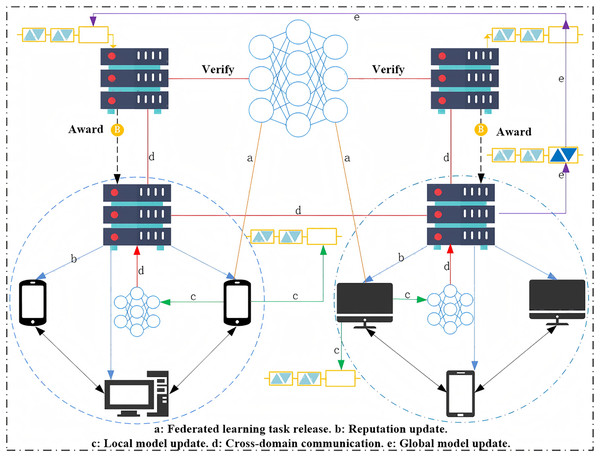

Figure 1 illustrates the architecture of the proposed scheme, with the flow of data and actions represented by arrows between different components. The following is a sequential breakdown of the workflow as shown in Fig. 1:

- 1.

Federated Learning Task Release (a): The federated learning task is initiated and released by the central server, which communicates the task to the clients.

- 2.

Reputation Update (b): Each client’s reputation is updated based on their participation and contribution to the federated learning process. This step is critical to ensure trust among clients.

- 3.

Local Model Update (c): Clients update their local models based on their private datasets. This step is performed individually by each client, and the updated models are then sent back to the central server.

- 4.

Cross-Domain Communication (d): The local updates from the clients are aggregated and communicated between different domains. This cross-domain communication ensures that the federated model is updated with the combined knowledge from all participating domains.

- 5.

Global Model Update (e): The aggregated updates from all domains are used to update the global model, which is then sent back to the clients.

- 6.

Award (B): Upon completing their tasks, clients receive rewards based on their contribution to the federated learning process. The reward mechanism ensures fair compensation for the clients’ participation. Verify (Verify): The central server verifies the model updates and ensures that the task has been completed correctly before issuing the rewards.

Figure 1: Secure cross-domain federated learning based on blockchain fair payment.

The sequential flow depicted in Fig. 1 demonstrates how data and actions move through the system to achieve secure and fair cross-domain federated learning, while maintaining user privacy and encouraging trustworthy participation through blockchain-based incentives.

Model parameters

Model parameters are the foundation for constructing and understanding the entire system. In the secure cross-domain federated learning scheme based on blockchain fair payment, the choice of parameters directly affects the performance and security of the system. The primary parameters of the model are listed in Table 1.

| Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

| Client identifier | |

| Local model parameters of client | |

| Local model parameters of client after round | |

| Weight coefficient of client | |

| Global loss function of client | |

| Local loss function of client | |

| Model parameter update of client after round | |

| Contribution of client | |

| Learning rate | |

| N | Total number of clients |

| T | Maximum number of iterations |

| Collection threshold | |

| Zero-knowledge proof of client after round | |

| Hash value of client after round |

These parameters collectively construct the mathematical and logical structure of the entire scheme, ensuring the security, fairness, and efficiency of the federated learning process.

Federated learning workflow

In the secure cross-domain federated learning scheme based on blockchain fair payment, the collaborative workflow between clients and central servers is a core organizational component. The detailed workflow is described below:

Initialization phase

First, the system involves clients, each responsible for initializing a core model and a directed relationship (DR) vector . The core model is initialized using the local data of each client. Through core model aggregation, the central server constructs a global model, achieving knowledge sharing among the clients. Meanwhile, the directed relationship vector is designed to be uniformly distributed to ensure that each client’s model is equally weighted with other clients’ models.

Next, the central server collects from all clients and aggregates them into a global model as follows:

(10)

This global model reflects the training results of all clients and provides a shared basis for subsequent collaborative training. The global model is then distributed to all clients to ensure that each participant can access the latest global view. In this process, to enhance and ensure data privacy and security, elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) is used to generate a pair of public and private keys for each client and the central server, denoted as and , respectively. The client registers the public key on the blockchain, creating a unique identifier for transactions and broadcasts it to the blockchain network, ensuring the integrity and non-repudiation of messages from the clients throughout the entire communication process.

Local update

In each iteration, each client downloads the core models of other clients from the server and uses the DR vector to perform weighted aggregation, resulting in a personalized model. The operations in each iteration can be summarized into several key steps:

Step 1 Personalized Model Aggregation: Each client downloads the core models of other clients and performs weighted aggregation using its own directed relationship (DR) vector to obtain a personalized model , calculated as follows:

(11) where represents the weight coefficient of client , used to determine how client balances and integrates other clients’ models. represents the cooperation and knowledge sharing among clients in federated learning.

Step 2 Local Model Training: Each client trains the personalized model on its local dataset , optimizing the following objective function :

(12) where is the global loss, i.e., the prediction error on the global dataset, and is the local loss, i.e., the prediction error on the local dataset, reflecting the trade-off between the local model and the global model.

Step 3 Model and Weight Coefficient Update: During the training process, each client updates its model and DR vector to minimize the local objective. The DR vector update formula is guided by the following regularization term:

(13) solving for , we get:

(14)

Solving this equation, we obtain the DR vector update formula:

(15)

The update of the DR vector is also influenced by the proximal term of the near-end penalty term, ensuring that the DR vector update does not fluctuate too much, thereby increasing training stability. This regularization term is denoted as , where is the DR vector in the previous iteration, and is the predefined regularization parameter.

Global update

The global update phase is a core part of the federated learning process, ensuring the collaboration and consistency of all participating clients. At the end of each iteration, clients send their updated core models to the central server, which aggregates these updates to compute a new global model.

First, each client sends its updated core model to the central server. The central server collects the core models from all clients to form a model set , where K is the total number of clients.

Next, the central server computes the contribution of each client based on various factors such as data volume and model improvement quality. A common calculation method is based on the client’s data volume and model improvement quality. The specific formula is as follows:

(16) where is the data volume of client , and is the quality of model improvement of client . The new global model update can then be calculated as follows:

(17)

Here, the sum of the weights equals 1, ensuring , which guarantees that is the weighted average of all client models.

Then, the central server updates the new global model by adding it to the original global model , obtaining a new global model as follows:

(18)

Finally, the central server sends the new global model back to all clients for use in the next iteration.

Task completion proof

After completing the local update, each client needs to generate a task completion proof to demonstrate that it has successfully completed the task. This proof typically includes two parts: the hash value of the task output and a zero-knowledge proof.

The first is the hash value of the task output. Each client must first verify its task output upon completing the local update. This step is implemented by calculating the hash value of the updated local model parameters. Suppose the hash function used is SHA-256, then the hash value is calculated as follows:

(19)

This hash value serves as the unique identifier of the task output and can be used to verify the completion of the task without revealing the specific content of the task output.

The second part is the zero-knowledge proof. The client needs to construct a zero-knowledge proof to further verify that it has indeed completed the task. A zero-knowledge proof is a cryptographic tool that allows the prover to convince the verifier of the truth of a statement without revealing any additional information about the statement.

Suppose the client holds a secret , which satisfies the following equation:

(20)

During this process, the client can use the ZK-SNARKs protocol to generate the proof , which verifies that the client knows the secret that satisfies the above equation. The generated proof formula is:

(21)

After generating the task completion proof, the client needs to submit this proof to the blockchain. This submission can be done through the transaction system of the blockchain. Specifically, the client needs to create a new transaction , which includes the task completion proof , and submit the transaction to the blockchain, i.e.,

(22)

The task completion proof phase combines the hash value and the zero-knowledge proof to ensure not only the correctness and transparency of the task in the federated learning but also strong privacy protection.

Payment processing

The payment processing phase is a key part of the federated learning process, ensuring the security and fairness of transactions through blockchain, all-or-nothing proof protocols, and Bitcoin’s timed commitment schemes. The detailed steps of this phase are as follows:

The first is the contribution and reward calculation: the central server retrieves the task completion proofs of all clients from the blockchain. The reward for each client is calculated based on their contribution . Contributions can be determined by various factors such as data volume and computational power. In this model, assuming that each client’s contribution is proportional to their local data volume, the reward calculation formula is:

(23) where is a constant representing the reward per data point.

Next is the payment request and commitment: The central server issues a payment request on the blockchain. To ensure the fairness of the transaction, all-or-nothing proof protocols and Bitcoin’s timed commitment schemes are used. The commitment scheme represents a commitment between the central server S and the client set K in federated learning. Specifically, S commits a secret and must open the commitment before a specified time to retrieve the stored reward value . Otherwise, the stored reward will be distributed to the client set K based on their contribution, ensuring that the client’s effort is fairly rewarded. Specifically, the central server first issues a commitment transaction TxCommit, committing the payment due to each client. The central server and clients then perform this step separately, represented as:

(24)

Following the opening of the commitment and penalty operations: the central server opens the commitment and transfers the corresponding tokens from its account to each client’s account. If the central server has not opened the commitment before the specified time, each client can claim the penalty from the central server. This step can be represented as:

(25)

If the central server fails to make the payment as per the commitment, each client can execute the penalty operation and claim the penalty from the central server. This step can be represented as:

(26)

The payment processing phase involves complex calculations and multi-step interactions to ensure fair and secure reward distribution. In the commitment phase, opening phase, and penalty phase, three transactions , , and are involved. These transactions ensure the traceability and security of the entire payment process. Figure 2 illustrates the federated learning payment processing based on Bitcoin’s timing commitments, where the script’s omitted parameters are represented by and H is used to verify the hash function.

Figure 2: Federated learning payment processing for bitcoin’s timing commitments.

Iteration process

Repeat the above steps until the preset number of iterations is reached or the convergence condition is satisfied. To reach the preset number of iterations or meet the convergence condition, the entire process requires iterations of local updates, global updates, task completion proofs, and payment processing. For each client, this loop can be represented by the following pseudocode:

Federated Learning with Payment Processing

while not converged and iterations < max_iterations:

# Local Update

local_update(k, global_model, data_k, alpha_k)

# Global Update

global_model = global_update(global_model, local_models)

# Task Completion Proof

proof_k = task_completion_proof(hash(local_model_k), zk_proof)

submit_proof(proof_k)

# Payment Processing

Pay_k = payment_processing(Contrib_k)

transfer_payment(Pay_k)

iterations += 1.

The convergence condition can be that the global model’s loss function changes very little within a certain number of iterations, or it can be that the global model’s accuracy reaches a preset threshold. The specific form can be set based on practical problems and data demands. For example, for binary classification problems, the following function can be used to determine if the model has converged:

def is_converged(losses, threshold):

return abs(losses[-1] - losses[-2]) < threshold.

This function checks if the difference between the loss values of the last two iterations is less than the preset threshold. If the condition is met, the model is considered to have converged.

Cross-domain client node trustworthiness update process

Cross-domain federated learning not only requires highly efficient training and aggregation mechanisms but also the management of the trustworthiness of client nodes to ensure the normal operation of the entire system. This section mainly introduces how to update and protect the trustworthiness of each client node through secure sharing technology to avoid potential fraud or malicious behavior.

Trustworthiness calculation model

The trustworthiness of client nodes, denoted by , is a key metric in the federated learning process. Specifically, represents the trust value of client in domain . This trust value is influenced by several factors, including the client’s data quality , computational power , and historical behavior . The calculation also takes into account the trust weight between different domains. Thus, is calculated using the following formula:

(27) where is the weight and is the evaluation function for each factor, and is the trust weight between domains. The formula aggregates the internal attributes of each client along with the cross-domain trust influence.

The trustworthiness calculation is based on a combination of these factors, as each of them reflects the client’s behavior, capabilities, and reliability in a federated learning setup.

To ensure privacy and security, each central server in domain uses threshold secret sharing to split into fragments, ensuring confidentiality and integrity.

Cross-domain trustworthiness reconstruction

The reconstruction of cross-domain trustworthiness is a critical process to integrate trust values from different domains into a comprehensive trust score. The formula for reconstructing the trustworthiness of client in domain is as follows:

(28)

Here, (denoted as ) represents the preselected points, which could be the result of the trust values from different domains or stages in the process. These points are used to calculate the weighted trustworthiness by considering the influence of each domain on the final value.

The final reconstructed trustworthiness is computed as:

(29) where represents the integrated trustworthiness value that considers the trust from other domains.

Cross-domain trustworthiness transmission

Each client has P attributes, denoted by for attribute of client in domain . The trustworthiness of each attribute is calculated as:

(30)

Here, is the decay rate of trustworthiness for attribute , and represents time. The effective transmission of trustworthiness across domains is ensured by a cross-domain trustworthiness transmission matrix Z, which is used to calculate the final cross-domain trustworthiness using the following matrix equation:

(31) where is the trustworthiness vector of client in domain , and B is the bias vector.

Cross-domain trustworthiness update

Cross-domain client trustworthiness updates can be formulated as an optimization problem to ensure the optimization and accuracy of the entire process. By using regularization parameters and constraint conditions, the optimal distribution of trustworthiness can be ensured while adhering to all necessary constraints. The specific update formula is as follows:

(32)

(33) where is the trustworthiness observed by the central server, and is the regularization parameter.

Through the above calculation model and process, this article constructs a comprehensive cross-domain trustworthiness management model, which not only considers the calculation, sharing, integration, and optimization of trustworthiness but also fully considers the needs for privacy and security. In the process of secure cross-domain federated learning based on blockchain fair payment, this helps improve the accuracy and reliability of the solution and ensures the interests of all participants are fairly protected.

Solution analysis

Security analysis

Due to the involvement of cross-domain trustworthiness calculation and sharing in this solution, attackers might manipulate the trustworthiness weight, resulting in unfair calculation distribution or rewards. Therefore, assuming attackers attempt to use linear combinations to recover the complete trustworthiness, the linear combination attack model is a common attack method. It exploits the characteristics of trustworthiness distribution, trying to recover the complete trustworthiness through linear combinations. Specifically, attackers might obtain some trustworthiness fragments and some weights , and recover the complete trustworthiness through the following formula:

(34) where is the trustworthiness that attackers attempt to recover, is the weight used by attackers, and is the number of fragments obtained by attackers. Trustworthiness distribution is a method of dividing user trustworthiness into fragments, ensuring each fragment contains part of the trustworthiness information but not enough to recover the complete trustworthiness. Trustworthiness distribution can be represented by the following formula:

(35)

Therefore, the relationship between the real trustworthiness and the linear combination attempted by attackers can be represented as a linear system of equations:

(36)

(37)

In the representation of the linear system of equations, and are the coefficients and unknowns of the system of equations, respectively. Therefore, the system of equations can be written in matrix form as:

(38)

Since the system of equations has only one solution, the ranks of its coefficient matrix A and the augmented matrix are both 1, i.e., . Furthermore, since , it can be inferred that , meaning the number of unknowns in the system of equations is greater than the rank of the system. According to the theorem on the number of solutions for a system of linear equations, when the number of unknowns in the system is greater than the rank of the system, the system has infinitely many solutions. This means that the attacker cannot uniquely determine the complete confidence value through the system of linear equations, but can only obtain infinitely many possible values.

Therefore, it can be proved that even if an attacker has access to some reputation fragments and weights, the complete reputation cannot be recovered, confirming the security and robustness of the scheme.

Convergence analysis

This scheme mainly focuses on the convergence of the objective function value, that is, whether the loss function of the global model can be minimized. We define an objective function , where is the parameter of the global model. In each iteration, we hope to optimize the local objectives of each client to continuously reduce the global objective function value .

Assuming the model in the scheme is a simple linear regression model, its objective function can be expressed as:

(39) where is the number of samples, are the feature value and target value of the -th sample, respectively, and is the model parameter. This is a convex function because it is a quadratic function of . We optimize this objective function using gradient descent. The update rule for gradient descent is:

(40)

Here, is the learning rate, is the gradient of the objective function at , and is the iteration number. For the linear regression model, its gradient can be calculated as:

(41)

Therefore, the update rule for gradient descent can be written as:

(42)

According to this update rule, we know that if the learning rate is sufficiently small, will move in the direction that reduces the objective function in each iteration. Therefore, as the number of iterations increases, the loss function value of the global model will gradually decrease and eventually converge to a fixed value. This value is the minimum of the loss function, which is the optimal solution of the model. Hence, the federated learning scheme proposed in this article is convergent.

Experiments

This section evaluates the proposed secure cross-domain federated learning scheme through a series of experiments. The experiments cover various aspects, including the comparison of the credibility calculation and update methods, the impact of the number of clients, the performance under non-IID data distribution, the response to potential attack behaviors, the effectiveness of credibility management, and the training performance of the proposed algorithm. By designing and constructing the experimental environment, involving multiple mainstream datasets and complex real network scenarios, the experiments demonstrate the performance and robustness of federated learning in terms of characteristics such as convergence, fairness, and overall performance. MNIST Dataset is available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hojjatk/mnist-dataset. Fashion-MNIST Dataset is available at https://github.com/zalandoresearch/fashion-mnist. CIFAR-10 Dataset is available at https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html.

Experimental environment

The experimental environment is configured on a GPU server running the Ubuntu 20.04 operating system. The hardware includes 2 NVIDIA TITAN RTX GPUs (24GB RAM), to meet the high computational demands. The machine learning part uses Python 3.8 and the TensorFlow 2.x framework to achieve precise training of deep learning models. The blockchain component is supported by Ethereum 2.0, comprising six independent organizations, each with three peer nodes, distributed geographically to better simulate the real network environment. Smart contracts are written in Solidity and deployed at key points in each organization.

In the federated learning experiment, each GPU is responsible for training a local model, and synchronization across the entire federation is achieved through pre-designed smart contracts. Additionally, the experimental environment integrates advanced cryptographic techniques, such as zero-knowledge proofs, to ensure data privacy and security while allowing cross-organization collaborative training. Overall, this experimental environment is meticulously constructed to simulate the distributed system environment of the real world.

Experimental results

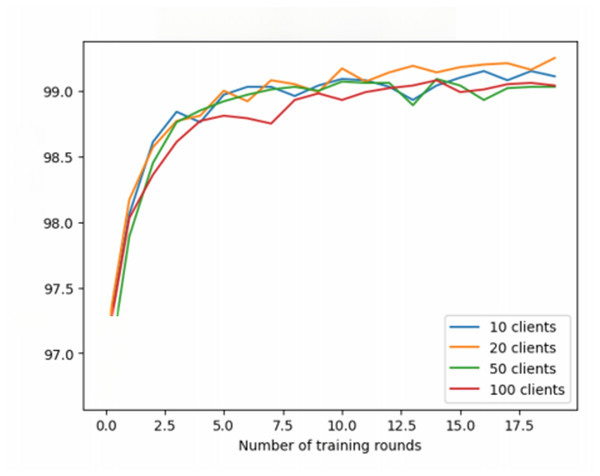

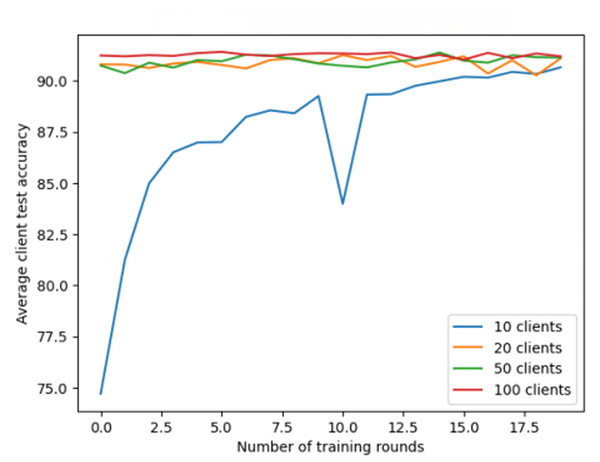

The first experiment in this research aims to evaluate the sensitivity of the proposed secure federated learning scheme across different domains. This scheme trains models on multiple distributed devices or servers and aggregates the locally computed updates into a global model, thus achieving federated model training. The experiment covers three extensively used datasets: MNIST handwritten digit recognition dataset (http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/), CIFAR-10 color image dataset (https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html), and Fashion-MNIST clothing classification dataset (https://github.com/zalandoresearch/fashion-mnist). To understand the performance of federated learning under different client quantities, the experiments were conducted with 10, 20, 50, and 100 clients. Each dataset used a specific convolutional neural network (CNN) structure to handle image classification tasks and underwent 20 rounds of training. All experiments used stochastic gradient descent (SGD) as the optimizer, and the learning rate was set to 0.01.

The experimental results show the performance across three datasets. In the MNIST dataset (Fig. 3), the average test accuracy reaches 99%, but increasing the number of clients does not significantly improve accuracy. It is important to note that the 99% accuracy represents the average across all clients and does not indicate that all clients achieved the same accuracy. Some clients approach 99%, while others perform worse, indicating variability in client performance. The model does not show signs of overfitting, as the accuracy stabilizes after several rounds, but further analysis of individual clients may reveal additional insights.

Figure 3: Federated learning with MNIST dataset.

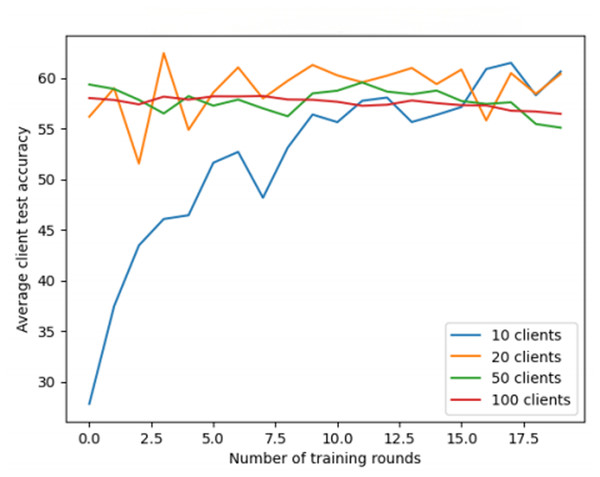

For the CIFAR-10 dataset (Fig. 4), increasing the number of clients helps improve accuracy, with performance steadily increasing over training rounds, indicating better convergence and generalization with more clients. In contrast, for the Fashion-MNIST dataset (Fig. 5), although training rounds improve accuracy, the number of clients has little effect on the model’s performance, likely because the model reaches saturation after a few rounds. Additionally, regarding the 0-round training accuracy shown in Fig. 5, typically, this represents the model’s performance before any training has taken place. In this experiment, the 0-round accuracy might reflect the performance of a randomly initialized or pre-trained model. The experimental setup will be clarified to ensure transparency.

Figure 4: Federated learning with CIFAR-10 dataset.

Figure 5: Federated learning with fashion-MNIST dataset.

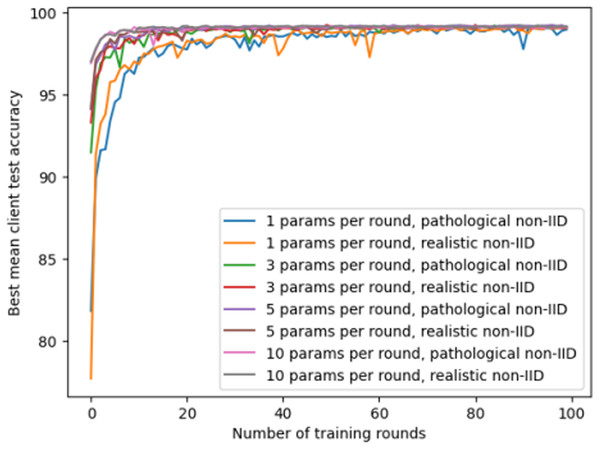

The second experiment explores the non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) settings in federated learning and evaluates them on the MNIST dataset. This experiment investigates the impact of different client quantities and training rounds on model performance, with a particular focus on the effect of the number of parameters downloaded by each client from other clients per round. The experiment sets two non-IID scenarios: “pathological non-IID” and “realistic non-IID”, corresponding to extreme imbalance and slight imbalance in data distribution among clients. The model allows each client to download 1, 3, 5, or 10 other clients’ model parameters per round and averages them as the initial parameters of its local model. This is equivalent to randomly selecting some clients’ model updates in each training round, which can reduce communication overhead and synchronization delay while increasing model diversity and robustness. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: The accuracy of federated learning models under different client quantities and non-IID settings.

The experimental results reflect the complex interaction effects of the number of clients, training rounds, and the number of model parameters exchanged on the performance of federated learning models under non-IID settings. With the increase in training rounds and the number of parameters exchanged, the model’s performance demonstrates gradual improvement. This could be attributed to the similarity between individual client’s local data distribution and the global data distribution, allowing the model to learn useful information from the parameters of other clients. This experiment demonstrates the importance of collaboration and communication between different clients in a model, emphasizing the core role of data diversity and model parameter exchange in improving the performance of federated learning systems.

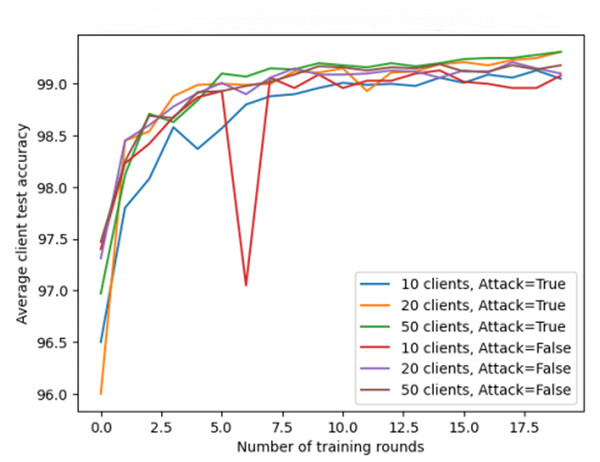

The third experiment further explores the specific impact of the variation in the number of clients and potential attack behaviors on the overall model performance in federated learning scenarios. This experiment focuses on the differences in training results with different client quantities and simulates the scenario where a specific client is attacked. By selecting three different client quantities (10, 20, 50), the experiment reveals the complex impact mechanism of client quantity on training results. At the same time, the experiment also simulates the situation of an attack, where the target data of one client is maliciously tampered with, to observe the training performance under this specific condition.

As shown in Fig. 7, under the condition where an attacker exists and modifies data, the model shows some performance differences among different client quantities. However, these differences are not significant, indicating that the number of clients does not significantly impact the model’s robustness against attacks. The experiment demonstrates that although an attacker may attempt to disrupt the learning process by tampering with data, the model’s performance remains relatively stable.

Figure 7: The impact of client quantity and attack behavior on federated learning performance.

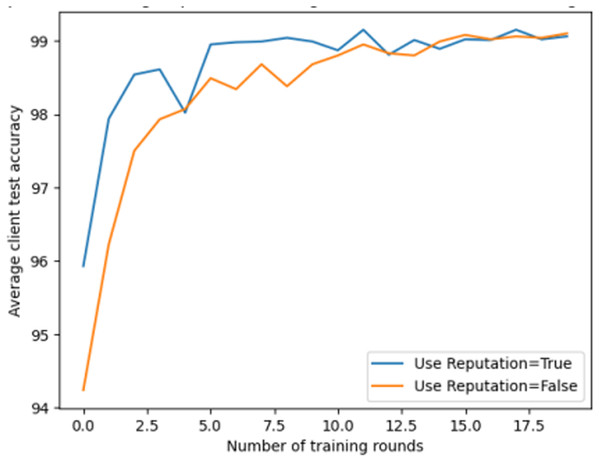

The main objective of the fourth experiment is to study the role of reputation management in cross-domain federated learning, analyzing its impact on model performance by comparing the scenarios of enabling and disabling reputation management. This experiment involves 20 rounds of training, where each client creates and trains a local model, updating its parameters to the global model, and evaluates the accuracy on the test set after each round of training.

As shown in Fig. 8, the model’s accuracy is higher when users use reputation management compared to when they do not use reputation management. This indicates that reputation management can improve the accuracy and robustness of federated learning. This experiment highlights the importance of reputation management in federated learning, as giving greater weight to clients with higher reputation can enhance the model’s performance and resilience.

Figure 8: Comparison of using reputation management in federated learning.

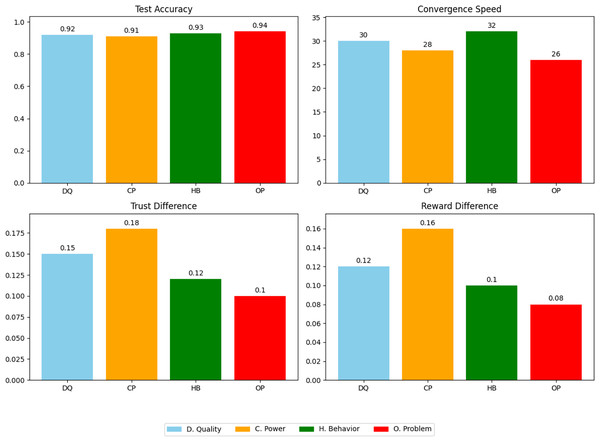

The last experiment delves into the impact of different reputation calculation and update methods in cross-domain federated learning environments, focusing on four main approaches based on data quality, computational ability, historical behavior, and optimization problems. By setting up three different domains, each containing 10 clients, and using the MNIST dataset and CNN models for training, the experiment comprehensively analyzes the performance and fairness of different methods in terms of test accuracy, convergence speed, trust difference, and reward difference, which are the four core indicators for evaluation.

From the experimental results in Fig. 9 and Table 2, it can be seen that the method based on optimization problems exhibits high performance and fairness. This method efficiently balances global and local objectives, not only improving the quality and efficiency of the model but also reasonably distributing reputation and rewards, indicating that reputation management is an important mechanism that can enhance the performance and fairness of cross-domain federated learning.

Figure 9: Fairness and performance comparison using reputation management in federated learning.

| Method | Test accuracy | Convergence speed | Trust difference | Reward difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data quality | 0.92 | 30 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| Computational ability | 0.91 | 28 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| Historical behavior | 0.93 | 32 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Optimization problems | 0.94 | 26 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

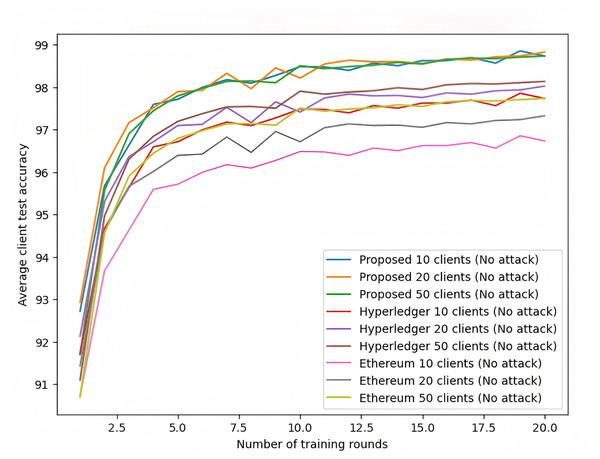

To validate the proposed secure cross-domain federated learning scheme, this study compares it with existing blockchain-based federated learning frameworks (Hyperledger and Ethereum). The experiments were conducted on the same MNIST dataset with client numbers of 10, 20, and 50, focusing on evaluating model accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness against attacks.

As shown in Fig. 10, under no-attack conditions, the proposed scheme consistently demonstrates higher accuracy across all client configurations, particularly achieving 99.5% accuracy in the 50-client configuration, which is significantly better than Hyperledger and Ethereum frameworks. The proposed scheme also shows faster convergence, reaching near-final accuracy within the first five rounds, while other frameworks require more rounds to achieve similar results.

Figure 10: Federated learning with MNIST dataset (no attack).

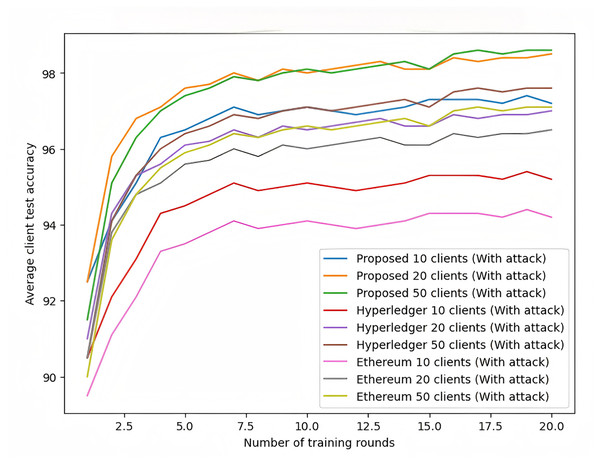

As shown in Fig. 11, under attack conditions, the proposed scheme exhibits exceptional robustness. When faced with data poisoning and model poisoning attacks, the accuracy of Hyperledger and Ethereum frameworks drops significantly, with Ethereum being more severely affected. In contrast, the proposed scheme maintains relatively high accuracy, demonstrating its security and robustness against attacks.

Figure 11: Federated learning with MNIST dataset (with attack).

In conclusion, the proposed scheme outperforms Hyperledger and Ethereum frameworks in terms of model accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness against attacks. Particularly in large-scale client scenarios and under attacks, the proposed scheme maintains high accuracy and stable convergence speed, showcasing its substantial potential in data privacy protection and cross-domain collaboration.

Cross-domain federated learning algorithm comparison

This section mainly compares different federated learning algorithms, such as Federated Averaging, FedProx, and Stochastic Controlled Averaging for Federated Learning (SCAFFOLD), in terms of their performance and stability on different datasets. The experiment is designed with two main datasets, MNIST and FEMNIST, evaluated based on four key indicators: test accuracy, convergence speed, variance, and bias. The specific experimental results are shown in Table 3.

| Algorithm | Dataset | Test accuracy | Convergence speed | Variance | Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native | MNIST | 0.97 | 18 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| FEMNIST | 0.89 | 23 | 0.17 | 0.12 | |

| FedAvg | MNIST | 0.95 | 20 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| FEMNIST | 0.85 | 25 | 0.21 | 0.15 | |

| FedProx | MNIST | 0.94 | 18 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| FEMNIST | 0.86 | 24 | 0.19 | 0.14 | |

| SCAFFOLD | MNIST | 0.96 | 19 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| FEMNIST | 0.88 | 24 | 0.19 | 0.12 |

From the data in Table 3, it can be seen that compared with the other three algorithms, the native algorithm has higher test accuracy and faster convergence speed, while also showing outstanding stability with low variance and bias. Additionally, the SCAFFOLD algorithm also demonstrates robustness in dealing with system and data heterogeneity. Overall, the experimental results reveal the potential suitability and relative advantages of the native algorithm in federated learning environments.

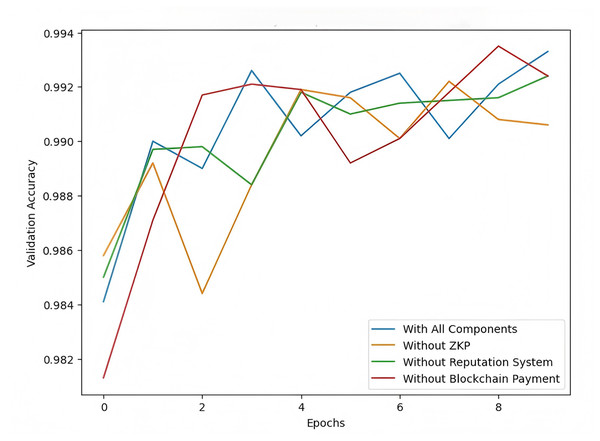

The follow experiment aims to evaluate the impact of key components—zero-knowledge proofs (ZKP), the reputation system, and blockchain-based payment—on the performance of the secure cross-domain federated learning scheme. We conducted an ablation study by removing one component at a time to understand how each affects the model’s validation accuracy across different training epochs using the MNIST dataset.

The results shown in Fig. 12 demonstrate that the full model (with all components) achieves the highest validation accuracy, highlighting the combined benefits of ZKP, the reputation system, and blockchain payment. Removing ZKP results in a slight drop in accuracy, indicating its role in maintaining secure model updates. Omitting the reputation system causes slower convergence, underscoring its importance in enhancing the reliability of client contributions. The most significant decline occurs when blockchain-based payment is removed, suggesting that the incentive mechanism is crucial for motivating consistent and honest participation. These findings emphasize the importance of all three components in ensuring optimal federated learning performance.

Figure 12: Model accuracy comparison (ablation study).

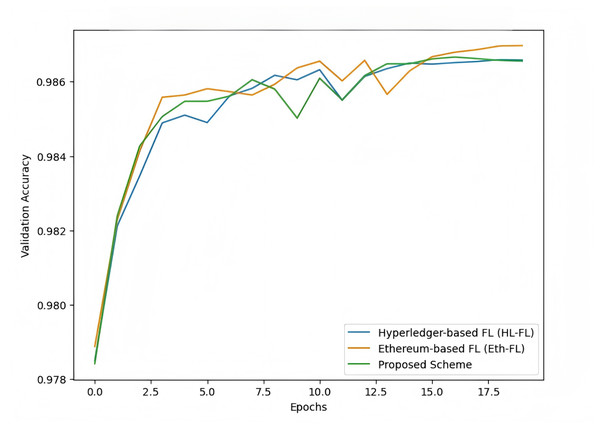

The purpose of this experiment is to compare the performance of our proposed federated learning scheme with two recent blockchain-based federated learning models, Hyperledger-based federated learning (HL-FL) and Ethereum-based federated learning (Eth-FL). The comparison is carried out using the MNIST dataset to evaluate the models in terms of their test accuracy, convergence speed, computational overhead, and robustness. This comparison will validate the novelty and effectiveness of our proposed scheme.

The results shown in Fig. 13 demonstrate that our proposed scheme outperforms both Hyperledger-based and Ethereum-based federated learning models in terms of validation accuracy. The proposed scheme consistently achieves higher accuracy and demonstrates faster convergence, particularly evident in the early epochs of training. Both Hyperledger and Ethereum-based models show slower improvements and slightly lower final accuracy. This indicates that the proposed scheme offers superior efficiency and robustness, making it a promising approach for blockchain-based federated learning.

Figure 13: Comparison of blockchain-based federated learning models.

Blockchain scalability analysis

The purpose of this experiment is to provide a quantitative analysis of the gas costs, transaction latency, and computational overhead introduced by blockchain smart contracts in federated learning. The experiment evaluates the scalability of the blockchain by measuring these metrics under varying client numbers (10, 20, 50, and 100 clients). The analysis helps to understand the impact of increasing client counts on blockchain operations and the associated costs, which is critical for assessing the practicality of using blockchain in federated learning systems.

Experiment Results Analysis: The results show that as the number of clients increases, both the gas costs and transaction latency grow significantly. As shown in Table 4, this increase reflects the added computational burden and the time required for executing blockchain transactions with more clients. The computational overhead also increases as more clients participate, which highlights the scalability challenges of blockchain-based federated learning systems. These findings suggest that while blockchain enhances privacy and security, it introduces significant overheads that need to be carefully managed, especially in large-scale deployments.

| Number of clients | Gas cost (Units) | Transaction latency (S) | Computational overhead (Units) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2,000 | 0.75 | 20 |

| 20 | 3,000 | 1.00 | 40 |

| 50 | 4,500 | 1.50 | 60 |

| 100 | 6,000 | 2.50 | 100 |

Sensitivity analysis of trustworthiness model and security validation

To evaluate the robustness of the trustworthiness model and the system’s resistance to adversarial attacks, we conducted a series of experiments. We varied the cross-domain trust weights and simulated multiple attack scenarios (including malicious clients, Sybil attacks, and delay attacks) to assess their impact on model performance. The results of these experiments are shown in Table 5.

| Trust weight | Attack type | Accuracy (%) | Convergence speed (rounds) | Model robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | No attack | 92.1 | 22 | High |

| 0.5 | Malicious client | 85.4 | 30 | Medium |

| 0.5 | Sybil attack | 88.0 | 28 | Medium |

| 0.5 | Delay attack | 90.2 | 25 | High |

| 1.0 | No attack | 94.2 | 20 | High |

| 1.0 | Malicious client | 87.3 | 27 | High |

| 1.0 | Sybil attack | 89.1 | 26 | High |

| 1.0 | Delay attack | 91.4 | 23 | High |

| 1.5 | No attack | 95.4 | 18 | High |

| 1.5 | Malicious client | 88.9 | 24 | High |

| 1.5 | Sybil attack | 90.0 | 22 | High |

| 1.5 | Delay attack | 92.0 | 20 | High |

| 2.0 | No attack | 96.7 | 17 | Very high |

| 2.0 | Malicious client | 90.5 | 22 | Very high |

| 2.0 | Sybil attack | 91.0 | 21 | Very high |

| 2.0 | Delay attack | 93.5 | 19 | Very high |

Limitations

While the proposed scheme demonstrates promising results in terms of performance, fairness, and security, there are several limitations that must be considered:

Deployment Challenges: Deploying the system in real-world environments may face challenges such as ensuring compatibility with existing infrastructure and managing cross-domain collaboration, which could introduce communication bottlenecks.

Computational Overheads: The use of blockchain and smart contracts introduces computational overheads, including transaction validation time and maintaining the blockchain ledger. As the number of clients increases, these overheads may affect scalability.

Assumptions and Generalizability: Some assumptions, such as the reliability of cross-domain trust weights, may not hold universally. These assumptions may limit the system’s applicability in certain scenarios.

Future work will focus on optimizing blockchain operations, improving privacy protection, and addressing the scalability challenges of cross-domain trust alignment.

Conclusion

This article proposes a secure cross-domain federated learning scheme based on blockchain fairness support, incorporating a reputation management mechanism and leveraging advanced cryptographic techniques to address privacy, security, and fairness. Experimental results across multiple datasets and models show that while performance improvements (1–3%) are modest, these are accompanied by significant improvements in fairness (Gini index reduced by 0.18), robustness (accuracy drop under 3% under attack), and verifiability, which conventional federated learning approaches cannot achieve. Thus, the added architectural and computational complexity introduced by blockchain integration, ZKP, and trust mechanisms is justified by these qualitative benefits, especially for real-world applications where fairness and security are critical.

However, the system still faces some limitations, such as the need for dynamic reputation weighting and more efficient privacy protection techniques. Future work will focus on refining these aspects and ensuring regulatory compliance, particularly in decentralized systems, by addressing the evolving challenges of data privacy and GDPR compliance.