G-Pro bot: a GraphRAG-powered GIS (Geographical information system) chatbot

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Varun Gupta

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Computer Education

- Keywords

- Chatbot, GraphRAG, Large language model, Geographical information system

- Copyright

- © 2026 Wang and Li

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. G-Pro bot: a GraphRAG-powered GIS (Geographical information system) chatbot. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3520 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3520

Abstract

Generative artificial intelligence (GAI) is gaining increasing popularity, but its applications in the Geographical Information System (GIS) domain remain limited. Consequently, answers to domain-specific questions often lack depth and specialization. GraphRAG presents a promising solution by building a knowledge graph, integrating contextual information from a knowledge base, and generating higher-quality answers. In this study, we use GraphRAG to enhance a pretrained large language model (LLM) through a retrieval-augmented generation framework, presenting a domain-specific chatbot named G-Pro Bot. Our evaluation, which includes both automated and manual evaluation, confirms the strong performance of G-Pro Bot in comprehending GIS knowledge and generating accurate, context-aware responses compared with baseline models. This makes the G-Pro Bot well suited for use in GIS education and decision-support scenarios. To the best of our knowledge, this research represents one of the earliest applications of GraphRAG in the development of a GIS chatbot, and it validates a lightweight, resource-accessible strategy for building high-performing, domain-specific artificial intelligence (AI) systems. The findings provide a valuable blueprint for creating reliable and easily deployable question-answering systems in other professional fields.

Introduction

The emergence of generative artificial intelligence (GAI), such as ChatGPT, Sora, Bard, and QWen, has revolutionized how we approach and solve complex problems across diverse fields (Dwivedi et al., 2023). OpenAI’s GPT-3, which launched in 2020, quickly gained traction across various applications because of its exceptional capabilities in semantic understanding, matching, and generation (Teubner et al., 2023). These advancements have enabled the GAI to excel in specialized domains, such as health care, law, and journalism, where it has been used to generate pathology diagnostic reports, automate contract drafting, and produce news articles (Bhayana, 2024; Williams, 2024; Pavlik, 2023). However, the application of the GAI in highly specialized and interdisciplinary fields, such as geographic information systems (GISs), remains underexplored and faces significant challenges.

In the field of GIS, the application of GAI has demonstrated significant potential (Moreno-Ibarra et al., 2024; Li & Ning, 2023; Wang et al., 2024). Companies such as ESRI and Google have introduced GAI-based assistants to help users query data, perform spatial analysis tasks, and automatically generate maps (Turner, 2024; Maguire, 2024). These tools are highly valuable for GIS professionals, primarily focusing on task automation and operational efficiency for users who already possess foundational GIS knowledge. However, a different but equally important challenge lies in supporting non-experts who are just beginning to navigate the complex, interdisciplinary nature of GIS—which spans geography, computer science, and data analysis (Mansourian & Oucheikh, 2024). This highlights a distinct need for a specialized chatbot focused on knowledge retrieval and explanation, capable of not only answering GIS-related questions but also providing comprehensive context to help users derive insights from spatial data. Such a system would complement existing task-oriented tools by democratizing access to complex GIS knowledge, fostering wider understanding and application.

Current general-purpose GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT and Ernie Bot) face significant limitations in their performance within the GIS domain. Owing to the complexity, specialization, and interdisciplinary nature of GIS knowledge, these tools often struggle to provide in-depth or specific responses to GIS-related queries (Zhang et al., 2024a; Deng et al., 2024). For example, when it is asked about specific GIS software operations, a general-purpose GAI tool may provide vague or incomplete instructions rather than precise commands or parameter details. This limitation highlights a critical gap in the market: the need for a chatbot that can comprehend GIS knowledge and generate more comprehensive and accurate responses.

To address these challenges, we use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), a technique that improves large language models (LLMs) by integrating external knowledge bases to increase the accuracy and professionalism of generated text (Lewis et al., 2020; Ge et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2020). However, the RAG method has limitations, particularly in complex reasoning tasks, where its simple retrieval-generation process struggles to capture the complex interrelationships among pieces of information (Qian et al., 2024a, 2024b; Guo et al., 2024). Recently, emerging GraphRAG has addressed these shortcomings by building a knowledge graph (KG), namely, recognizing entities within the corpus, establishing connections, and building relational networks. This approach enables text retrieval to extend beyond isolated sentences or paragraphs, significantly increasing the depth and coherence of generated responses (Edge et al., 2024; Peng et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2024). In July 2024, Microsoft open-sourced its own GraphRAG project. With its strong performance and accessibility, the project demonstrates its potential for application in specialized fields such as GIS.

On the basis of these advancements, we established a specialized GIS knowledge base and applied Microsoft’s GraphRAG framework to improve a LLM. By constructing a GIS-specific knowledge graph, we developed G-Pro Bot, a chatbot designed to address the unique challenges of the GIS chatbot field. Unlike existing solutions, the G-Pro Bot excels in generating comprehensive, accurate, and contextually rich responses to GIS-related queries. The ability of the G-Pro Bot to bridge the gap between technical complexity and user accessibility makes it a valuable tool for both GIS education and decision-making scenarios.

Materials and Methods

G-Pro bot development

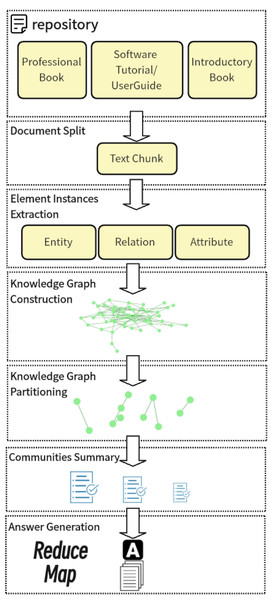

In this section, first, we construct a GIS knowledge base, which includes introductory books, professional books and software operation manuals. Second, we chunk the text for the subsequent steps. We then extract key information, such as entities, relationships, and attributes, from the chunked text. On the basis of this extracted information, we build a knowledge graph (KG)—a structured representation of knowledge using nodes for entities and edges for relationships—and apply the Leiden algorithm to partition the graph into communities. With the LLM, we generate a hierarchical community abstraction. After a query is received, the answer is generated via the abstraction created in the previous step. The development of the G-Pro Bot is completed through the steps outlined above. The overall construction process is based on Microsoft’s GraphRAG project (Microsoft, 2024), which leverages knowledge graphs to structure information, enabling a more comprehensive and precise retrieval of interconnected facts and entities for augmented generation. The development workflow of the G-Pro Bot is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: G-Pro bot developing workflow.

GIS knowledge base construction

The quality of G-Pro Bot’s answer generation, in terms of comprehensiveness, richness, and depth, relies greatly on the documentation that forms the basis of its knowledge. Therefore, we constructed a GIS knowledge base that establishes a balance between breadth and depth. The knowledge base consists of three main components:

- 1.

Software operation manuals: GIS applications are highly reliant on software for tasks ranging from spatial analysis to map visualization. Thus, knowledge related to software operation is crucial. We selected tutorials and user guides for three popular GIS programs—ArcMap, ArcGIS Pro, and QGIS—to ensure that G-Pro Bot incorporates knowledge at the technical operation level.

- 2.

Introductory books: This section includes classic introductory books that address fundamental GIS concepts, with core topics such as entities, spatial analysis, and coordinate systems. These books not only broaden the knowledge base but also serve as key resources for the entities extracted during the KG construction process.

- 3.

Professional books: To further expand the knowledge base and answer interdisciplinary questions, this section presents professional literature on the application of GIS in specific fields, such as criminology and hydrology.

The knowledge base comprises 12 comprehensive documents, totaling approximately 948,758 words. While this collection is not exhaustive, its volume is substantial enough to serve as a robust proof-of-concept for this study. The curated size allows us to rigorously test the GraphRAG methodology within a specialized domain while maintaining a manageable computational burden for deployment and reproducibility. To ensure the quality of this foundation, we selected authoritative and relevant texts. For theory, this includes classic works such as Geographic Information Analysis and Geographic Information Systems in Oceanography and Fisheries, which remain foundational in the field. For practical application, we selected the most up-to-date user guides available for major GIS software. The detailed information of the literature included in the knowledge base is presented in Table 1.

| Title | Type | Author and ISBN |

|---|---|---|

| GIS Tutorial for ArcGIS Desktop 10.8 (Gorr & Kurland, 2021) | 1 | Gorr & Kurland, 2021; ISBN: 9781589486140 |

| GIS Tutorial for ArcGIS Pro 3.1 (Gorr & Kurland, 2023) | 1 | Gorr & Kurland, 2023; e-ISBN: 9781589487406 |

| QGIS-3.34-DesktopUserGuide-en (Utton & Colin, 2021) | 1 | Utton & Colin, 2021 |

| Spatial Analysis Methods and Practice Describe–Explore–Explain through GIS (Grekousis, 2020) | 2 | Grekousis, 2020; ISBN 978-1-108-49898-2 |

| Geographic Information Analysis (O’Sullivan & Unwin, 2002) | 2 | O’Sullivan & Unwin, 2002; ISBN 978-0-470-28857-3 |

| Introducing Geographic Information Systems with ArcGIS A Workbook Approach to Learning GIS (Kennedy, Goodchild & Dangermond, 2011) | 2 | Kennedy, Goodchild & Dangermond, 2011; ISBN 978-1-118-15980-4 |

| Introduction to Geographic Information Systems (Chang, 2019) | 2 | Chang, 2019; ISBN 978-1-259-92964-9 |

| Computing In Geographic Information Systems (Panigrahi, 2014) | 2 | Panigrahi, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4822-2314-9 |

| Geographic Information Systems in Urban Planning and Management (Manish Kumar et al., 2023) | 3 | Manish Kumar et al., 2023; ISBN 978-981-19-7854-8 |

| Geographical Information System and Crime Mapping (Kannan & Singh, 2020) | 3 | Kannan & Singh, 2020; ISBN: 9780367359034 |

| Geographic Information Systems in Oceanography and Fisheries (Valavanis, 2002) | 3 | Valavanis, 2002; ISBN 0-203-30318-0 |

| Geographic Information Systems in Water Resources Engineering (Johnson, 2009) | 3 | Johnson, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4200-6913-6 |

After collection, all documents were standardized into a plain text corpus using a Python script. This preprocessing included removing non-textual content and redacting any potential personally identifiable information (PII) to ensure data privacy and ethical compliance, with the full script available as a Supplemental File.

With respect to sensitive information redaction, this process was performed to safeguard individual privacy and ensure ethical data handling. The categories of sensitive information targeted included, but were not limited to, personally identifiable information (PII), such as personal names, phone numbers, email addresses, home addresses, and specific highly identifiable geographical coordinates or postal codes. This proactive measure is essential because documents, even from publicly accessible sources, may contain PII, risking privacy leakage of generative results (Zeng et al., 2024). This process ensures data anonymization while maintaining the integrity of the core GIS content.

LLM integration and enhancement

The state-of-the-art LLM, Llama3.1-8B (Grattafiori et al., 2024), and the embedding model, Nomic-Embed-Text (Nussbaum et al., 2024), were selected to be integrated and improved in conjunction with GraphRAG. Llama3.1-8B is widely used for pretraining tasks because of its multilingual support and outstanding performance. Additionally, its context length of 128K enables it to handle long texts effectively, making it particularly well suited for G-Pro Bot’s knowledge integration and generation tasks. Nomic-Embed-Text, one of the most influential text embedding models, achieves excellent performance in processing both short and long text tasks.

Our selection of Llama3.1-8B was guided primarily by a balance between its demonstrated strong performance in various natural language understanding tasks and its computational efficiency and accessibility. While there are larger parameter models (e.g., 70B parameters or more) that provide impressive capabilities, their deployment typically requires substantial computational resources and entail considerably longer initialization and inference times. By focusing on an 8B parameter model, our study demonstrates the efficacy of the GraphRAG approach within a more resource-accessible framework, making our findings more readily transferable and reproducible for researchers with conventional computational setups. We acknowledge that exploring the performance gains of GraphRAG when they are integrated into even larger foundational models is a valuable direction for future research.

The GraphRAG implementation process was conducted on a computer equipped with an NVIDIA Quadro RTX 8000 GPU with 48 GB of memory.

Together, GraphRAG, Llama3.1-8B, and Nomic-Embed-Text collaborate to facilitate knowledge integration and response generation for G-Pro Bot, as outlined in the process below. To perform the same setup and implementation, please download the project on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/16730421.

- 1.

Source document split: The corpus is divided into text chunks via GraphRAG, which serve as the basis for extracting the knowledge graph. Overlaps between chunks are managed to ensure semantic continuity.

- 2.

Element instances extraction: GraphRAG is employed to identify extraction instances from the text chunks, focusing first on entities (e.g., names, types) and then on relationships between entities and their attributes. These extracted instances are managed as the basis for constructing the knowledge graph.

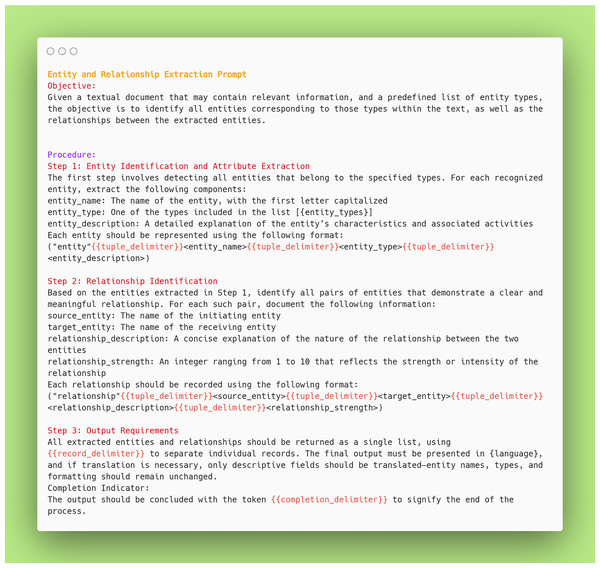

The core extraction methodology for GraphRAG that we used is LLM prompting. Our chosen LLM, Llama3.1-8B, is used for this purpose. For entity extraction, the LLM is prompted with specifically crafted instructions to identify named entities and generate their descriptive attributes from each text chunk. Simultaneously, for relationship extraction, the LLM is prompted to describe the connections and their types between identified entity pairs within each text unit. The specific prompts used for these initial extractions are detailed in Fig. 2. In this generative process, the LLM directly outputs the structured entities and relationships on the basis of its understanding of the provided text and prompt.

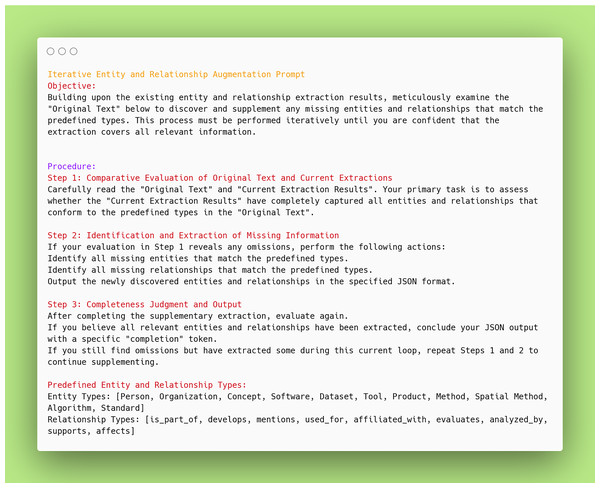

To address the challenge of missing instances, GraphRAG implements an iterative and self-correcting extraction mechanism. After an initial extraction pass, the system can use specific prompts to guide Llama3.1-8B to reevaluate and iteratively extract any remaining missing entities or relationships. The specific prompts used for this iterative re-evaluation and extraction process are also presented in Fig. 3. This multipass approach significantly improves the recall of the extraction process.

- 3.

KG construction: GraphRAG generates a preliminary knowledge graph via the extracted entities and relationships, with entities represented as nodes and relationships as edges.

- 4.

KG partition: The KG is partitioned into communities using a community detection algorithm, which determines the strength of the relationships between nodes. Specifically, we use the Leiden algorithm, which excels at recovering the hierarchical community structure of large-scale graphs. Each community corresponds to a set of semantically related entities and relationships and is mutually exclusive. The hierarchical nature of the community divisions ensures that the G-Pro Bot can provide fine-grained answers ranging from a global scope to a local scope.

- 5.

Community summaries generation: GraphRAG defines the hierarchy of summary generation, from overviews to communities, and manages the semantic information for each community. Llama3.1-8B generates natural language summaries on the basis of the extracted entities, relationships, and community content, ensuring that the summaries are both comprehensive and fluent.

- 6.

Answer generation: With hierarchical community summaries, the answer generation process is conducted in two phases. The first phase, known as the map phase, involves Llama3.1-8B, which generates localized answers on the basis of community summaries relevant to the query. To increase the relevance of the retrieval results, Nomic-Embed-Text is employed to generate vector embeddings for entities, relationships, and community summaries. These embeddings enable the identification of the most relevant communities or entities for a given query on the basis of vector similarity, increasing the accuracy of information retrieval. The second phase, the reduce phase, integrates the localized answers into a comprehensive global response, with Llama3.1-8B refining the linguistic style to align with the user query.

Figure 2: Entity and relationship extraction prompt.

Figure 3: Iterative entity and relationship augmentation prompt.

Implementation details and hyperparameters

After thorough debugging and testing, the following parameters were determined to be optimal for our system performance and are listed in Table 2. A complete and detailed list of all the configuration parameters and hyperparameters used in this study is provided at Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/16730421), in addition to the full codebase.

| Parameter category | Parameter name | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall system | GraphRAG version | 0.5.0 |

| Large language model-deployment & core architecture | Model | Llama3.1-8B |

| API key | Ollama | |

| API Base URL | http://localhost:11434/v1 | |

| Model supports JSON output | TRUE | |

| Hidden size | 4,096 | |

| Intermediate size | 14,336 | |

| Number of attention heads | 32 | |

| Number of hidden layers | 32 | |

| Vocabulary size | 128,256 | |

| Max position embeddings | 131,072 | |

| RoPE Theta | 500,000 | |

| Large language model-generation configuration | Do sample | TRUE |

| Temperature | 0.2 | |

| Top-P sampling | 0.9 | |

| BOS Token ID | 128,000 | |

| EOS Token ID | 128,001 | |

| Embedding model | Model | Nomic-Embed-Text |

| API key | Ollama | |

| API base URL | http://localhost:11434/v1 | |

| GraphRAG framework-core settings | Parallelization stagger delay | 0.3 |

| Async mode | Threaded | |

| GraphRAG framework-text processing | Chunk size | 300 tokens |

| Chunk overlap | 200 tokens | |

| Group type | Sentences | |

| GraphRAG framework-knowledge graph construction | Max gleanings for claim extraction | 1 |

| Max cluster size for community detection | 10 | |

| Embed graph enabled | FALSE | |

| GraphRAG framework-snapshots | GraphML snapshot enabled | TRUE |

| Raw entities snapshot enabled | FALSE |

G-Pro bot evaluation

After we completed the development of G-Pro Bot, we extracted 1–2 key points from each document in the corpus to serve as questioning material. A total of 22 questions were obtained. To evaluate the performance of GraphRAG in terms of contextualization and considering the close relationship between GIS and software operations, we designed four categories of questions: general questions, specific questions, general questions about software, and specific questions about software. The 22 questions and their respective categories are presented in Table 3.

| No. | Category | Question |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | General | What Are Spatial Analysis and Geospatial Analysis? Is There Any Difference Between These Terms? |

| 2 | What Is Classification of Measurement Levels? | |

| 3 | Introduce Kriging and All Members of the Kriging Family. | |

| 4 | What Is Edge Effect and How to Counter It? | |

| 5 | What Are Uses of GIS? | |

| 6 | List the Examples of Applications of Geographic Information Systems in Urban Planning and Management. | |

| 7 | What Are the Applications of GIS in the Field of Crime? | |

| 8 | What Is the Use of GIS in Various Fields of Oceanography? | |

| 9 | List the Fisheries GIS Tools and Initiatives. | |

| 10 | What Are the Types of Data Used for Surface-Water Hydrology Studies? | |

| 11 | I’m Mapping Floodplain, What Kinds of Data Should I Use? | |

| 12 | Specific | What Is Spatial Data? Give Me Some Examples of Data Types Included in Spatial Data. |

| 13 | What Is Map Projection? | |

| 14 | What Is Vectorization and Rasterization? | |

| 15 | What Is the Location Quotient in Spatial Crime Mapping? | |

| 16 | What Is Viewshed Analysis and What Does the Accuracy of Viewshed Analysis Depend On? | |

| 17 | Software-related general | How to Work with File Geodatabases in ArcMap? |

| 18 | Introduce the GUI of QGIS to Me. | |

| 19 | Software-related specific | How to Geocode Data by Zip Code in ArcMap? |

| 20 | How to Manage Plugins in QGIS? | |

| 21 | How to Create Charts in ArcGIS Pro? | |

| 22 | How to Create a TIN Surface in ArcGIS Pro? |

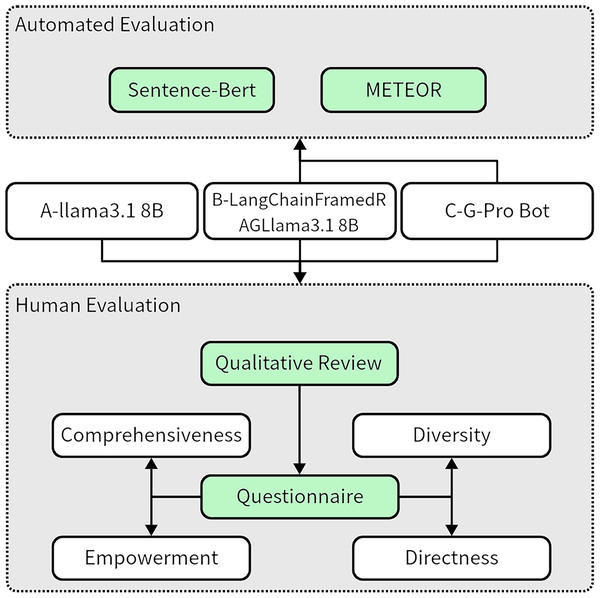

The questions above were used to query three chatbots, including the G-Pro Bot, and the responses were collected and organized, yielding three datasets with a total of 66 responses for subsequent evaluation. The evaluation process is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: G-Pro bot evaluation process.

Baseline

To comprehensively evaluate the G-Pro Bot (C-Model), we selected two baseline models for comparison, each serving a distinct purpose in our evaluation design.

The first baseline is Llama3.1-8B (A-Model). This LLM, developed by Meta AI, features 8 billion parameters and is capable of performing a wide range of natural language processing tasks (Shui et al., 2024). According to the original study, Llama3.1-8B has performed well compared with its counterparts in generalization, coding, mathematics, and reasoning through comprehensive automated and manual evaluations (Grattafiori et al., 2024). In our study, we use Llama3.1-8B without any RAG integration to represent the performance of a powerful, general-purpose LLM when faced with domain-specific queries. The second baseline, LangChainFramedRAG Llama3.1-8B (B-Model), was specifically constructed to compare the performance of our GraphRAG approach with that of a conventional RAG implementation. Using the LangChain framework (LangChain, 2024), we built this model to access the same GIS knowledge base as our G-Pro Bot, allowing for a direct comparison of the retrieval and synthesis capabilities.

Our evaluation strategy utilizes these models differently across its two stages. The human evaluation includes all three models (A-Model, B-Model, and C-Model) to gain a holistic view of user-perceived quality. In contrast, the automated evaluation focuses exclusively on the two corpus-aware models (B-Model and C-Model), as it measures performance against standard answers derived directly from our knowledge base.

While some commercial GIS-specific AI tools, such as those offered by ESRI or Google, are highly valuable for the GIS community, they typically focus on understanding and automating direct, straightforward GIS analytical tasks or operations based on explicit commands. In contrast, the G-Pro Bot is designed as a conversational chatbot that is focused primarily on knowledge retrieval and synthesis from a specialized GIS knowledge graph, providing comprehensive and contextually rich textual answers to natural language queries. Because of this fundamental difference in their operational paradigms—task automation vs. conversational knowledge Q&As—these commercial tools were not directly comparable baselines for our knowledge-based chatbot.

Evaluation methodology

Automated evaluation methodology

Our automated evaluation assesses the semantic similarity between model-generated responses and a set of standard answers. Crucially, these standard answers were generated directly from our processed GIS corpus to ensure factual grounding and comprehensiveness. Therefore, this evaluation is specifically designed to compare the performance of the two models that utilize this corpus: our G-Pro Bot (C-Model) and the LangChainFramedRAG Llama3.1-8B (B-Model). The A-Model (plain Llama3.1-8B) was excluded from this part of the evaluation, as it does not have access to the knowledge base, and comparing it against corpus-derived answers would be inappropriate. On this basis, we analyze the discrepancies between the chatbot-generated responses and the standard answers.

The standard answers used for the automated evaluation were established through a rigorous two-stage process to ensure their accuracy and comprehensiveness. First, initial answers were generated directly from our processed GIS corpus using the ChatGPT-4.0 API. Subsequently, these machine-generated answers underwent a critical review by multiple independent experts holding master’s degrees in GIS from our institute. The experts unanimously confirmed that the answers fully addressed the questions without factual errors, thus validating them as a robust ground truth for our evaluation.

Afterward, we evaluated the responses generated by the two corpus-aware models against the standard answers. To ensure a comprehensive and objective assessment, we employed two automated methods: Sentence-BERT (SBERT) (Reimers & Gurevych, 2019) for its high efficiency and strong performance in measuring semantic similarity (Ha et al., 2021; Joshi et al., 2022), and METEOR (Banerjee & Lavie, 2005) for its accuracy and sensitivity in evaluating text generation quality by incorporating recall and fragmentation penalties.

Human evaluation methodology

As part of the comprehensive human evaluation, a preliminary qualitative review of all the generated responses was conducted by multiple independent experts who hold master’s degrees in GIS from our institution. This review identified general performance patterns and potential error types, including hallucination, omission, irrelevant detail, and lexical redundancy.

To complement the qualitative review and obtain a quantified and diverse set of subjective opinions, we subsequently employed a comprehensive questionnaire. For this evaluation, we collected and assessed the responses generated by all three chatbots: the baseline Llama3.1-8B (A-Model), the LangChainFramedRAG Llama3.1-8B (B-Model), and our G-Pro Bot (C-Model). This questionnaire was administered to a broader pool of users to collect their evaluations of the responses generated by the three chatbots across four dimensions. This systematic approach allowed us to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the chatbots quantitatively from multiple perspectives.

1. Questionnaire design

The questionnaire is structured as follows: (a) Preface: This section introduces the purpose and organization of the questionnaire to the respondents. (b) Personal information: This section collects data on the teaching level and academic background of the respondents, which are used to analyze the evaluations of chatbots from users with different profiles. (c) Chatbot responses: This section presents the responses generated by the three chatbots to various questions. The respondents are asked to carefully read these answers and select the optimal answer on the basis of four specific dimensions. An example of the questionnaire interface is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Example of the questionnaire survey interface.

The two images on the left show the desktop version of the interface, while the two images on the right display the mobile version.The evaluation dimensions are based on the GraphRAG article (Edge et al., 2024) and include four aspects: comprehensiveness, diversity, empowerment, and directness.

Comprehensiveness assesses whether the answer addresses all aspects of the question, adequately addressing the key points. Diversity focuses on whether the answer presents diverse perspectives and insights. Empowerment evaluates whether the answer offers effective guidance or reference for the decision-making or judgment of the user. Directness assesses whether the answer clearly and concisely addresses the question without unnecessary elaboration.

To increase the robustness and generalizability of our results, a manual evaluation of the performance of the G-Pro Bot was conducted on all 22 questions and their corresponding three sets of responses.

2. Respondent selection and bias minimization

Owing to the specialization of the GIS and to validate the questionnaire results, we prioritized participants with backgrounds in geography-related majors. The respondents for this study were faculty members and graduate students from the Institute of International Rivers and Eco-Security at Yunnan University. This selection was based on a convenience sampling approach. The primary rationale for choosing individuals from a specific institute is their specialized knowledge and advanced understanding of a GIS, ensuring that the evaluations of model-generated responses are authoritative and discerning.

To reduce potential biases and ensure the objectivity of the human evaluation, several key measures were implemented:

Blind evaluation: All evaluations were conducted blindly to prevent any preconceived notions or favoritism toward specific chatbot identities. The identities of the three chatbot models were completely anonymized within the questionnaire. In the preface of the questionnaire, the respondents were explicitly informed as follows: ‘Please note that the chatbot identities have been anonymized, and your selections should be based solely on the content of the responses rather than the chatbot’s identity.’

Standardized evaluation criteria: The respondents were given clear and consistent guidelines for assessing responses across the four specified dimensions (comprehensiveness, diversity, empowerment, and directness), as indicated in the preface of the questionnaire. This standardized approach reduced subjective variability among the respondents.

Attention check question: An attention check question was included, and it was GIS related and involved three responses generated by ChatGPT-4 (as shown in Table 4), with increasing levels across the four dimensions. If a participant selected the least comprehensive, informative, and insightful response, their submitted questionnaire was considered invalid. The purpose of this step was to ensure evaluator attentiveness and to filter out careless responses, further mitigating potential bias from inattentive participation.

| Attention check question | Response A | Response B | Response C |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is Spatial Autocorrelation and its importance to geographical problems? | Spatial autocorrelation refers to the extent to which a phenomenon in a specific area is correlated with phenomena in surrounding areas. Positive spatial autocorrelation indicates that similar phenomena tend to cluster together, while negative spatial autocorrelation suggests that dissimilar phenomena are spatially separated. Its significance in geographic studies lies in its ability to help identify spatial patterns and distributions of phenomena, thereby optimizing resource allocation. | Spatial autocorrelation refers to the spatial correlation between phenomena within a geographic area. It helps us understand whether certain phenomena are distributed in a spatially patterned manner. Understanding this is valuable for the study of geographic issues. | Spatial autocorrelation refers to the correlation between the value of a phenomenon in a geographic space and the values of phenomena in its neighboring areas. Specifically, spatial autocorrelation can be categorized into positive and negative types. Positive spatial autocorrelation indicates that similar values tend to cluster together. For example, in certain areas, regions with high pollution concentrations are often adjacent to other areas with similarly high pollution levels. Negative spatial autocorrelation, on the other hand, implies that dissimilar values are spatially separated, such as different types of land use being distributed more dispersedly in space. Analyzing spatial autocorrelation is crucial for understanding the spatial distribution of geographic phenomena. By studying spatial autocorrelation, researchers can identify and explain the spatial patterns of certain phenomena, which is of significant importance for solving geographic problems. For example, in urban planning, by analyzing the land use patterns of different areas, policymakers can more effectively plan the layout of urban functional zones, ensuring the rational allocation of resources. In the field of public health, spatial autocorrelation analysis can reveal patterns of disease transmission, helping public health authorities implement more precise control measures. Furthermore, spatial autocorrelation analysis has broad applications in various fields such as environmental science, criminology, and socioeconomics. It aids researchers in identifying spatial hotspots or anomalous areas, providing strong data support for decision-making. Through spatial autocorrelation, researchers can not only uncover the spatial patterns of a phenomenon itself but also explore the interactions between different phenomena, revealing potential causal relationships. Therefore, spatial autocorrelation is not only an important tool in spatial data analysis but also a fundamental tool in multidisciplinary research. |

This study, which involves human participants, was reviewed and approved retrospectively by the Academic Committee of the Institute of International Rivers and Eco-security. An informed consent waiver was granted by the same committee due to the anonymous nature of the survey and the minimal risk involved.

Results

Automated evaluation results

We evaluated the generated responses via SBERT (a sentence embedding method for measuring semantic similarity) and METEOR (an evaluation metric for text generation that considers recall and multilevel matching). The SBERT similarity and METEOR scores for the generated responses of Model B and Model C (G-Pro Bot) are shown in Table 5. Model C outperforms Model B in terms of both evaluation metrics.

- 1.

SBERT similarity:

The G-Pro Bot outperforms Model B on 15 out of 22 questions, whereas Model B performs better on only seven questions. Notably, G-Pro Bot achieved significantly higher similarity scores (defined as a difference ≥ 0.1) in Q6, Q11, and Q15, whereas it scored significantly lower in Q4.

Focusing on general questions, the G-Pro Bot performed well for eight questions compared with only five questions for Model B.

- 2.

METEOR scores:

Compared with Model B, the G-Pro Bot achieved higher METEOR scores for 16 out of 22 questions, whereas Model B outperformed the G-Pro Bot by just six questions. Significant advantages for the G-Pro Bot were observed for Q2, Q5, Q7, Q11, Q15, Q16, Q17, and Q21, whereas Q10 and Q18 had significantly lower scores for the G-Pro Bot. In the subset of general questions, G-Pro Bot performed better for nine questions, whereas Model B was better for only four questions.

| SBERT similarity | METEOR score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question No. | B model | C model | B model | C model |

| 1 | 0.930458 | 0.93094 | 0.33125 | 0.328509 |

| 2 | 0.72232 | 0.8142 | 0.078286 | 0.27562 |

| 3 | 0.80941 | 0.80677 | 0.162252 | 0.21122 |

| 4 | 0.68934 | 0.322928 | 0.136863 | 0.19378 |

| 5 | 0.840437 | 0.88866 | 0.05571 | 0.17017 |

| 6 | 0.522691 | 0.65274 | 0.123057 | 0.12612 |

| 7 | 0.886166 | 0.91565 | 0.034439 | 0.17898 |

| 8 | 0.80561 | 0.799203 | 0.14381 | 0.23868 |

| 9 | 0.662738 | 0.69057 | 0.1634 | 0.118939 |

| 10 | 0.67137 | 0.605935 | 0.2617 | 0.050251 |

| 11 | 0.599683 | 0.77078 | 0.032258 | 0.14293 |

| 12 | 0.889897 | 0.90514 | 0.106342 | 0.19918 |

| 13 | 0.92017 | 0.928 | 0.239189 | 0.28329 |

| 14 | Not Applicable. Attention Check Question. | |||

| 15 | 0.723353 | 0.88158 | 0.079817 | 0.25221 |

| 16 | 0.88195 | 0.89411 | 0.209803 | 0.3392 |

| 17 | 0.816736 | 0.85897 | 0.133365 | 0.31896 |

| 18 | 0.552651 | 0.57211 | 0.20495 | 0.064312 |

| 19 | 0.64445 | 0.590234 | 0.121931 | 0.1834 |

| 20 | 0.763855 | 0.79796 | 0.176993 | 0.21978 |

| 21 | 0.59891 | 0.532614 | 0.131042 | 0.2363 |

| 22 | 0.562821 | 0.6233 | 0.22633 | 0.20323 |

| 23 | 0.7018 | 0.697412 | 0.28114 | 0.229776 |

Human evaluation results

In our initial qualitative review, evaluators observed distinct performance patterns: Model A produced clear but shallow instructional answers; Model B generated short and often incorrect responses; and G-Pro Bot delivered comprehensive, coherent explanations with strong reasoning, albeit with some verbosity. To complement this preliminary assessment and quantify these observed patterns, a structured error breakdown was conducted based on the error types identified during the initial review. Each model’s response to the 22 questions was manually examined for four distinct error types: Hallucination (generating factually incorrect or non-existent information), Omission (failing to include key information present in the source), Reasoning Error (making logical fallacies), and Irrelevant Detail (including information not pertinent to the question, contributing to verbosity). The results are presented in Table 6 and Table S1.

| Error type | A-model | B-model | C-model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hallucination | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| Omission | 10 | 21 | 5 |

| Reasoning error | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Irrelevant detail | 4 | 7 | 5 |

The findings provide a quantitative confirmation of G-Pro Bot’s superiority. Overall, G-Pro Bot (C-Model) committed the fewest error, compared to the baseline. A breakdown of key error types reveals:

- 1.

Omission: G-Pro Bot produced only five omission errors (Q11, Q12, Q16, Q18, Q22), compared to 10 for the A-Model and 21 for the B-Model.

- 2.

Hallucination: G-Pro Bot had two instances of hallucination (Q11, Q22), which was significantly lower than the B-Model’s six instances.

- 3.

Irrelevant detail: The five instances of irrelevant detail for G-Pro Bot provide a quantitative measure for its previously noted verbosity.

- 4.

Of its 12 total errors, G-Pro Bot committed only 2 on the 13 general questions, with the remaining 10 occurring on the five specific questions.

G-Pro Bot’s primary advantage lies in its significant reduction of Omission errors. It produced only 5 such errors, a stark improvement over the A-Model (10) and the B-Model (21). Furthermore, while not entirely immune to Hallucination, G-Pro Bot (two instances) demonstrated better factual grounding than the B-Model (six instances). Notably, the B-Model underperformed across all categories.

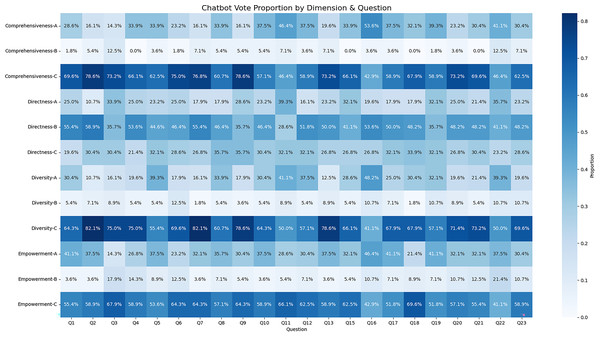

To complement this objective error analysis, we examine the quantitative data collected through the questionnaire. A total of 62 questionnaires were collected according to the methodology described in the Human Evaluation Methodology section. After the responses were filtered out with a completion time of less than 10 min, those with identical answers for all options and those for which the attention check question failed, a total of 56 valid questionnaires were retained. The results of the questionnaire analysis are presented in Fig. 6.

- 1.

Comprehensiveness: Model C (G-Pro Bot) was able to provide comprehensive answers for most questions (Q1–Q10, Q12–Q15, and Q17–Q23), outperforming both Model A and Model B. However, on Q11 and Q16, as shown in Fig. 6, compared with Model A, the G-Pro Bot exhibited the same and slightly lower performance.

- 2.

Diversity: In terms of diversity, the G-Pro Bot outperformed the other two models across all the questions, with the exception of Q16, where it was marginally inferior to Model A.

- 3.

Empowerment: The G-Pro Bot achieved the highest scores in empowerment across all the questions, with the exception of Q16.

- 4.

Directness: Model A and Model B performed well in directness across different questions.

- 5.

Performance on general questions: For the general GIS questions (Q1–Q11, Q18, and Q19), compared with Models A and B, the G-Pro Bot achieved significantly better overall performance.

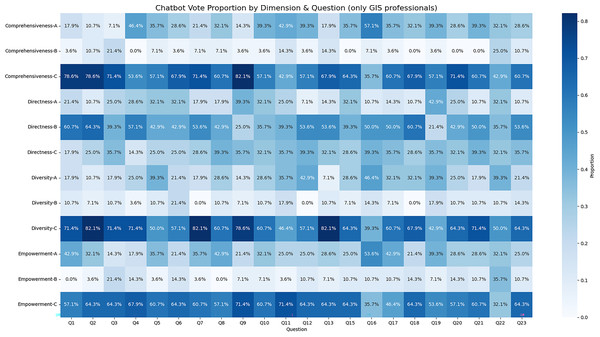

- 6.

Expert evaluations The responses from GIS professionals were consistent with the overall findings, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 6: Heatmap of three models’ performance across four dimensions in 22 questions.

The horizontal axis represents the 22 questions (Q1–Q22), while the vertical axis corresponds to the models and evaluation dimensions (e.g., comprehensiveness-A denotes Model A’s performance on the comprehensiveness dimension). In the heatmap, deeper blue indicates a higher number of votes. The percentage shown in each cell reflects the proportion of votes that a given model received in that dimension.Figure 7: Heatmap of three models’ performance across four dimensions in 22 questions (GIS professionals only).

This shows a heatmap similar to Figure, with data shown are from respondents with GIS-related backgrounds only. The horizontal axis represents the 22 questions (Q1–Q22), while the vertical axis corresponds to the models and evaluation dimensions (e.g., comprehensiveness-A denotes Model A’s performance on the comprehensiveness dimension). In the heatmap, deeper blue indicates a higher number of votes. The percentage shown in each cell reflects the proportion of votes that a given model received in that dimension.Validating the reliability of automated evaluation

This section assesses the reliability of SBERT and METEOR as automated evaluation metrics by examining their alignment with human assessments. To elucidate this relationship, we focus on questions where compared with other models, the G-Pro Bot model received notably higher or lower SBERT or METEOR scores (see Table 7). This targeted comparison elucidates how variations in automated scores indicate perceived response quality.

| Question no. | SBERT performance | METEOR performance | Human evaluation-comprehensiveness | Human evaluation–diversity | Human evaluation–empowerment | Human evaluation-directness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | / | Significantly higher | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 4 | Significantly lower | / | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 5 | / | Significantly higher | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 6 | Significantly higher | / | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 7 | / | Significantly higher | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 10 | / | Significantly lower | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 11 | Significantly higher | Significantly higher | Similar vote as model A | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 15 | Significantly higher | Significantly higher | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 16 | / | Significantly higher | Underperformed other models | Underperformed other models | Underperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 17 | / | Significantly higher | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 18 | / | Significantly lower | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

| 21 | / | Significantly higher | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Outperformed other models | Underperformed other models |

Our analysis reveals a nuanced relationship between automated metrics and human evaluation. We found that SBERT and METEOR scores strongly correspond with human judgments on content-focused dimensions: comprehensiveness, diversity, and empowerment. For instance, in responses to questions like Q2, Q5, Q6, Q7, Q15, Q17, and Q21, G-Pro Bot’s significantly higher automated scores were mirrored by superior human ratings in these three areas. This indicates that these metrics are effective at identifying semantically rich and informative answers.

However, the evaluation also highlighted the irreplaceable role of human judgment in capturing nuances that automated metrics miss. For example, for questions Q4, Q10, and Q18, G-Pro Bot received lower automated scores, yet was still preferred by human evaluators. This suggests that our model can deliver valuable content in ways not fully captured by similarity-based metrics, reinforcing the need for a complementary human assessment.

The most significant limitation of the automated metrics appeared in the evaluation of stylistic qualities, particularly directness. Across nearly all questions, G-Pro Bot was rated lower on directness by human evaluators, even when its SBERT and METEOR scores were high. This pattern confirms that semantic similarity metrics are not designed to measure conciseness. While a response can be comprehensive and contextually relevant (leading to a high automated score), it may simultaneously be verbose and lack the brevity that users value.

These findings underscore the need for more holistic evaluation frameworks that integrate both automated and human perspectives. Such future frameworks would benefit from validation across a larger, more diverse question set and with evaluators from multiple institutions to strengthen the generalizability of the results.

Discussion

This section comprehensively discusses the performance of the G-Pro Bot, integrating insights from both automated and human evaluations. We analyze its strengths and weaknesses, contextualize our findings by comparing them with the literature, and outline the practical implications of our research.

Strengths of the G-Pro bot

The evaluation results consistently highlight the excellent performance of the G-Pro Bot across multiple dimensions, revealing the significant advantages of the GraphRAG approach.

Enhanced semantic comprehension: The superior performance in automated metrics is not merely a statistical victory; it reflects a fundamental advantage of the GraphRAG architecture. By organizing knowledge into a relational graph, our system moves beyond the simple vector similarity search used in traditional RAG. This allows for the retrieval of a more cohesive and contextually complete set of information before generation, which logically results in a higher semantic alignment (measured by SBERT) and structural integrity (measured by METEOR) when compared to the ground truth answers.

Superior knowledge synthesis and comprehensiveness: The significant reduction in ‘Omission’ errors, as identified in our structured error analysis, offers the most direct evidence for G-Pro Bot’s superior knowledge synthesis and comprehensiveness. This finding is not an isolated observation but rather a direct manifestation of the GraphRAG framework’s architectural advantage. Unlike traditional RAG systems that rely on retrieving isolated text chunks and often fail to synthesize information scattered across a corpus (Chen et al., 2024), GraphRAG constructs a relational knowledge graph. This structure allows the model to traverse interconnected concepts, facilitating a holistic synthesis of information from multiple sources into a single, coherent response. Our work empirically validates what recent studies have theorized (Peng et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024b; Han et al., 2025): modeling relationships between entities is the key to a deeper understanding of a knowledge base. Therefore, this significant reduction in information gaps confirms that advancing from simple vector similarity searches to a graph-based retrieval approach is crucial for building effective domain-specific chatbots.

Robustness in handling general questions: A notable strength of the G-Pro Bot, substantiated by our error analysis, is its exceptional performance on general questions. This superiority is concentrated in the 13 general question (Q1–Q11, Q18, Q19). Across this category, G-Pro Bot committed only two minor errors, demonstrating remarkable robustness in synthesizing broad conceptual knowledge. This stands in stark contrast to the baseline models, which frequently failed on these same questions due to numerous ‘Omission’ and ‘Hallucination’ errors (see Table S1). This finding provides strong evidence that the GraphRAG approach, by organizing broad concepts and their relationships into a knowledge graph, enables the model to traverse interconnected information and construct more robust and comprehensive answers for questions that are not tied to a single, specific document chunk (Ngangmeni & Rawat, 2025; Zhang et al., 2024b).

Limitations and areas for improvement

Despite its overall strong performance, the G-Pro Bot presents several areas for improvement that highlight avenues for future research.

Misinterpretation and limitations in retrieving specific operational details: While G-Pro Bot demonstrated strong overall performance, our error analysis identified a specific limitation in retrieving fine-grained operational details. This issue was most apparent in responses to queries about specific software operations (e.g., Q18, Q22), where the model’s answers were often conceptually correct but lacked the precise, actionable steps a user would require. This occasionally led to ‘Omission’ errors where key procedural information was missing. This finding highlights a clear area for future improvement: refining the knowledge retrieval mechanisms to better balance high-level concepts with specific, procedural instructions.

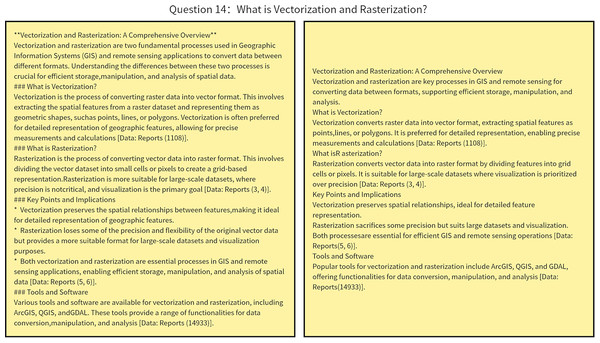

Improving directness and conciseness: Our initial evaluation revealed a tendency for G-Pro Bot to generate verbose, article-style answers. Acknowledging this limitation, we conducted a follow-up experiment to address this issue. We implemented two key changes: (1) prompt engineering, where we instructed the model to provide concise and direct answers by omitting introductory phrases and focusing on key points; and (2) parameter configuring. Specifically, we adjusted key generation parameters by reducing max_tokens to 1,024, adjusting temperature to 0.3, and setting repetition_penalty to 1.2 to discourage redundancy. We then regenerated answers for all 22 evaluation questions using this refined configuration. A qualitative assessment conducted by the authors confirmed that these changes yielded a significant improvement. The new responses are substantially more direct and less verbose, while still retaining the essential information required to answer the questions. An example of this improvement is provided in Fig. 8, and the full set of ‘before’ and ‘after’ responses is available in the Supplemental Material. This successful test confirms that the model’s verbosity can be effectively controlled, and future work will focus on systematically optimizing these settings, perhaps even allowing users to select their preferred response length.

Figure 8: Comparison of G-Pro bot’s response before and after optimization for conciseness.

The figure displays the responses to the question “What is Vectorization and Rasterization?” (Q14). The ’Before’ panel shows the original verbose, article-style response. The ‘After’ panel shows the significantly more direct and concise response generated after implementing prompt engineering and adjusting generation parameters. This example illustrates the successful mitigation of the model’s initial tendency towards verbosity.Computational complexity and its trade-offs: The primary trade-off of our accessible, high-quality approach is its computational complexity and consequently slower retrieval speed. Unlike traditional RAG, which retrieves simple text chunks, GraphRAG’s retrieval phase involves navigating complex graph structures. This multistage process is the key factor behind the slower response time of our G-Pro Bot. To address this limitation, we plan to explore the use of more efficient Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools, such as SpaCy, to automatically and quickly construct the knowledge graph. This approach could significantly reduce the computational overhead during the knowledge graph construction process, improving the overall response speed of the G-Pro Bot.

Limited scope of the knowledge base: While the 12 selected documents provide a solid foundation for this proof-of-concept study, they do not encompass the full breadth and depth of the highly interdisciplinary GIS field. Consequently, G-Pro Bot’s expertise is confined to the topics covered in this corpus. Future work should focus on significantly expanding the knowledge base with a wider range of literature—including advanced textbooks, recent research articles, and diverse software documentation—to enhance its comprehensiveness and its ability to address more complex, interdisciplinary queries.

Theoretical and practical implications

The contributions of this research are significant on both theoretical and practical levels, as discussed below:

Validation and extension of GraphRAG in domain-specific applications

This study is a rigorous case study that provides empirical evidence of the superiority of the GraphRAG framework in improving large language models (LLMs) for a professional domain, namely, GIS. While existing research often lacks a detailed performance analysis of GraphRAG technologies within specialized fields, our work systematically demonstrates how GraphRAG, by constructing a domain-specific knowledge graph, effectively increases the accuracy, comprehensiveness, and consistency of an LLM in handling complex, specialized queries. These findings not only reinforce the theoretical foundation of GraphRAG but also provide a valuable methodological blueprint for developing robust and reliable professional question-answering systems in other domains, such as medicine, law, or engineering.

A novel deployment of a GraphRAG chatbot for the GIS domain

We contribute to the GIS field by developing and deploying the G-Pro Bot, one of the first specialized chatbots to leverage the GraphRAG framework. The successful development of the G-Pro Bot fills a significant gap in the field by providing a solution that effectively handles complex, domain-specific queries and generates high-quality, contextually rich answers. Notably, its design as a deployable and user-friendly solution makes it readily applicable in GIS education and for assisting nonexperts with geographical information tasks, mitigating the barrier to GIS knowledge acquisition and broadening the application scope of this technology.

A lightweight strategy prioritizing accessibility and quality

Our research validates a “lightweight strategy” centered on the locally deployable Llama3.1-8B model. This approach proves that high-performing, professional-grade chatbots can be built without reliance on costly commercial APIs or the massive computational infrastructure required by larger models. Our definition of “lightweight” and “resource-accessible” therefore refers to the accessibility of deployment—making advanced AI available to researchers, educators, and small organizations with conventional hardware.

This strategic choice involves a deliberate trade-off: we prioritize the quality of the generated response and accessibility over raw inference speed. The computational intensity of GraphRAG, which leads to slower response times, is the direct cost of achieving deeper, more contextually coherent answers from a model that can be run locally. This makes G-Pro Bot a practical solution for scenarios like education and decision support, where the depth and accuracy of an answer are more critical than its instantaneous delivery.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a domain-specific chatbot focused on addressing questions within the GIS domain, including topics such as concepts, analysis methods, and software operations. The process began with the construction of a GIS knowledge base, followed by the application of GraphRAG—which uses knowledge graphs to enable more precise and grounded retrieval—to improve Llama3.1-8B, which resulted in the deployment of the G-Pro Bot. To the best of our knowledge, this study is among the first to apply GraphRAG in the development of chatbots within the GIS domain. The evaluation results reveal that G-Pro Bot outperforms both the pretrained models Llama3.1-8B and LangChainFramedRAG Llama3.1-8B in both automated and manual evaluation. This finding highlights its superior ability to comprehend the GIS knowledge base and generate accurate responses, highlighting the advantages of the knowledge graph approach of GraphRAG. Additionally, G-Pro Bot demonstrates the advantages of a lightweight, low-cost deployment strategy, which enables it to be more accessible for individuals and small-scale organizations. This work thus provides a valuable reference for developing more reliable and easily deployable question-answering systems in other professional fields.

However, our work also identified several significant limitations that must be addressed. First, the chatbot shows a limitation in handling queries for fine-grained, specific operational details, which occasionally resulted in ‘Omission’ and ‘Hallucination’ errors in our structured error analysis. Second, the system has a relatively slow response time, a direct trade-off resulting from the computational intensity of the GraphRAG approach. Third, our current knowledge base is limited in scope and does not yet cover the full breadth of the interdisciplinary GIS field. Finally, the generated answers show a tendency towards verbosity. Acknowledging this, we conducted preliminary experiments with prompt engineering and parameter configuring, which successfully produced more direct and concise responses without sacrificing essential information. This confirms the issue is addressable and will be a focus of future refinement.

To address these issues, our future work will focus on several key areas. We will optimize the underlying infrastructure and computational pipeline to increase response speed. We will systematically refine generation parameters and prompting strategies to ensure a better balance between comprehensiveness and directness. Furthermore, we will focus on improving the knowledge graph construction pipeline to better represent and retrieve both structured and unstructured information, and we plan to significantly expand the knowledge base to enhance the chatbot’s expertise. Future validation will also involve a larger question set and participants from multiple institutions to ensure our findings are more generalizable.

In conclusion, this work provides a valuable reference for developing more reliable and easily deployable question-answering systems in other professional fields, demonstrating the potential of a lightweight GraphRAG strategy. While G-Pro Bot shows clear promise, its current limitations mean that substantial refinements are needed before it can be considered a fully robust and user-centric GIS chatbot.

Supplemental Information

The new questionnaire containing all 22 questions in Chinese.

The new questionnaire containing all 22 questions in English.

The valid result of the new questionnaire from GIS professionals in English.

Detailed breakdown of errors by question and model.

This table provides the comprehensive, question-by-question log of all errors identified. It serves as the detailed supplementary data for the aggregated results presented in Table 6 of the main manuscript. For each of the 22 questions, the table indicates the specific error type(s) (Hallucination, Omission, Reasoning Error, or Irrelevant Detail) committed by each of the three models: A-Model (baseline Llama3.1-8B), B-Model (LangChainFramedRAG Llama3.1-8B), and C-Model (G-Pro Bot). The ’/’ symbol indicates that no errors were identified for that particular response.

Full comparison of G-Pro Bot responses before and after conciseness optimization.

This document provides the full set of responses for all 22 evaluation questions, serving as the detailed evidence for the optimization discussed in the "Improving Directness and Conciseness" section of the main manuscript. For each question, the original verbose response is presented first (non-highlighted text), followed immediately by the optimized, more concise response (gray-highlighted text).