Computational frameworks for interactive multimedia art installations in public spaces using real time digital control and visualization

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- José Alberto Benítez-Andrades

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computational Linguistics, Digital Libraries, Multimedia, Real-Time and Embedded Systems

- Keywords

- Interactive media (IM), Real-time visualization (RTV), Public art (PA), Max/MSP (Max/MSP), Touch designer (TD), Real-time multimedia architecture

- Copyright

- © 2026 Liu et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Computational frameworks for interactive multimedia art installations in public spaces using real time digital control and visualization. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3384 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3384

Abstract

Background

Interactive multimedia art installations in public spaces are evolving with the integration of real-time (RT) digital control and visualization technologies, enabling dynamic and immersive user experiences. These installations transform urban environments into responsive, participatory spaces through audiovisual interactivity. However, existing methods often face limitations such as inflexible architectures, latency in data processing, and challenges in real-time synchronizing multimodal inputs and outputs. These issues hinder scalability and reduce the creative possibilities of interactive systems in public settings.

Methods

This study proposes a Node-based Real-Time Multimedia Architecture using Max/MSP and (TD) Touch Designer (MAX/MSP-TD) to address these challenges. The framework leverages the strengths of visual programming environments, allowing seamless integration of real-time sensor data, audio analysis, and generative visuals through modular and reusable components. The proposed method is applied in an urban installation where sound and movement data from the public are captured and translated into interactive light and sound projections in real time. This encourages public engagement and offers a platform for creative expression within the built environment.

Results

Findings show that the MAX/MSP-TD framework significantly improves system responsiveness, flexibility, and scalability while enhancing user interaction and artistic control in public multimedia installations.

Prologue

In the 21st century, the divisions separating public space, technology infrastructure, and artistic expression are erasing (Hartley, Hodges & Finney, 2023). Cityscapes are now becoming dynamic canvases that serve more than just a background for people’s daily lives (Franklin, 2023). Artists and technologists create installations that respond to individuals’ presence, activities, and emotions (Golvet et al., 2022). Usually, with these kinds of undertakings, the line separating observer from member is somewhat porous (Dannenberg et al., 2021). The primary focus of this shift is integrating real-time, digital control, and visualizing technology (Ronen & Wanderley, 2024). Including generators, acoustic analysis, and generative media into the design process produces interactive installations (Martins, Lagrange & Tzanetakis, 2014). Apart from appreciating art, attendees at such events are urged to engage actively by moving, listening, and interacting with the works (Lindetorp & Falkenberg, 2020). Public spaces thus become venues for participative, always evolving expression (Tidemann, Lartillot & Johansson, 2021). It is not easy to implement those responsive systems. There is a lack of flexibility in many current multimodal models (Verdugo et al., 2022). The disruptions in the real-time (RT) experience are mostly occurred by the delays in data processing (Buffa et al., 2024). This design is inflexible, so, it is difficult to adapt to various backgrounds. This inflexibility also makes unexpandable installations (Braun, 2021). Here, there is a continual demand for technological advancements for synchronizing many kinds of content, including video, audio, and sensor data (Hynds et al., 2024). The interactive public art have the potential to address those limitations, as they define creative possibilities and accessibility (Leonard, Villeneuve & Kontogeorgakopoulos, 2020).

Effectively using a practical, adaptable, modular computational framework relies heavily on its flexibility and ease of integration (Van Kets et al., 2021). The promising outcomes in this field is demonstrated when using the visual programming tools like Touch Designer (TD) and Max/MSP (Snook et al., 2020). The creative processes are encouraged by its node-based architecture, and it doesn’t demand lot of coding (Zang, Benetatos & Duan, 2023). RT data visualization and fast prototyping are also facilitated by this application (Borg, 2020). For interactive multimedia systems, a robust model is attained by integrating those tools (Ward, 2023).

A novel MAX/MSP-TD framework is introduced initially in this article. It aims to free creative agency from technology constraints (Weins, 2022). The technical advancements may facilitate a more interactive, immersive, and inclusive public art (Carpentier, 2021).

Motivation: The rise of digital artwork and smart cities necessitates innovative approaches to public engagement through technology. Interactive multimedia exhibits offer intense, immersive experiences even if they have technological constraints. The construction of a real-time, adaptable framework in this work is motivated by improving artistic expression, enabling scalability, and inspiring greater public involvement in metropolitan locations.

Problem statement: Inflexible system architectures, prolonged delay, the risks in synchronizing many inputs and outputs of the media were the most common challenges when using interactive multimedia installations in public spaces. Thus, the developments, innovation and involvement in RT interaction has become more difficult by these constraints. So, there is a great demand for an adaptive, and flexible computing structure, because, this adaptable model facilitates interactive public engagement with audio visual data.

Contributions:

The three significant contributions are;

Development of a node-based real-time multimedia architecture: This study, utilizing MAX/MSP-TD, provides a scalable and flexible framework for interactive public art installations, enabling real-time integration of visual, audio, and sensor data.

Enhanced real-time responsiveness and synchronization: The suggested method greatly advances system efficiency and RT interaction in multimedia backgrounds.

Application in a real-world urban installation: The framework’s implementation in a public place offers improved public interaction and creative potential in the urban environment.

The corresponding testable hypotheses are:

- 1.

H1: Real-time sound input significantly alters the perceived quality of multimedia visual effects in interactive installations, with higher sound levels leading to more intense or complex visual patterns.

- 2.

H2: User engagement with the installation increases when the visual effects react dynamically to sound, as measured by interaction frequency, duration, and participant feedback.

- 3.

H3: The use of a modular, node-based framework (MAX/MSP-TD) provides greater flexibility and precision in adapting multimedia visuals to real-time environmental conditions compared to traditional, pre-programmed visual installations.

- 4.

H4: The inclusion of diverse sound levels (e.g., low, moderate, high) as control parameters produces distinct visual experiences that are perceived as interactive and responsive by users, enhancing the overall immersive experience.

The remaining sections of this article are organized as follows: ‘Related Works’ deals with analyses of related works; in ‘Proposed System’, we introduce the idea for the MAX/MSP-TD framework and explore its implications. We list the experimental results in ‘Results and Analysis’. ‘Conclusion and Future Work’ investigates the last idea and the possible results.

Related works

Due to advances in digital technology, artists may now include audiences with real-time audiovisual input. These works depend critically on sound, motion, or sensor data interpretation by reaction systems. Still, current systems usually have rigid architectures and poor real-time performance. The modular, adaptable control provided by node-based technologies like Max/MSP and TD will help to solve this issue. This article proposes a fresh framework using these technologies to enhance interaction, scalability, and creative freedom.

Draft/Patch/Weave

The following document describes an artistic endeavour combining modular synthesis with floor loom weaving by González-Toledo et al. (2023). The project’s central concept is the weaving draft, which uses Max/MSP to generate and comprehend here-and-now weaving instructions. This approach opens the path for performance-based linkages between modular synthesis and weaving, two fields typically unrelated. Driven by data and sensory interactions between digital and analog worlds, the system displays fresh approaches of creative expression via weavings, patches, and compositions.

Scheme for Max

Scheme for Max (S4M) integrates Scheme with Max/MSP to increase the platform’s capacity for precise event scheduling and live scripting by Cox (2021). This is an open-source application. By directly integrating Scheme functions with the Max scheduler, the principal approach provides exact control over musical tempo. Apart from that, users of the Max environment can script and assess code, providing further opportunities for generative design, real-time composition, and music computing.

Avendish and declarative media interfaces (ADMI) in C++

This article exposes problems with current abstraction techniques and offers a declarative approach for media processing using modern C++ reflection by Celerier (2022). The proposed approach uses a non-intrusive subset of the object model instead of class-based inheritance to overcome framework-specific restrictions when specifying media processors. The Avendish package is a nice illustration of this approach since it creates user and application programming interfaces (APIs) and automatically binds to interfaces like VST, Max, and Open Sound Control (OSC) during compilation.

Low-cost plant bio-signal interface

It presents a simple and cheap interface for transforming electrical signals from plants into digital data usable in creative media applications constructed with Max/MSP by Duncan (2021). Technology that records biosignals in their natural condition, free of anthropomorphic interpretations, is available for less than $5. These signals are used in real-time installations to start or regulate motion, music, or film. Through multimedia art and low-barrier, scientifically responsible methods of bio-interface, our technologies promote creative, polite interactions across species.

Binaural rendering toolbox

Designed for psychoacoustic research and 3D sound exploration, the Binaural rendering toolbox (BRT) is a SONICOM-developed modular software suite. The Avendish package provides C++ libraries for simulating listener-source interactions and environmental acoustics and links to well-known frameworks like Max/MSP and VST by Weinberg & Bockrath (2024). A breakthrough is its capacity to enable reproducible audio experiments using dynamic SOFA standards for geographical data. The BRT is an all-inclusive virtual lab for binaural audio research under OSC control.

The suggested MAX/MSP-TD system integrates real-time sensor input, auditory analysis, and visual output. It addresses media synchronization and latency in public interactive systems. Modular, reusable pieces enable rapid prototyping and environmental adaptation.

In our public testing show in Table 1, we effectively turned user movement and sound into live projections.

| S. No | Article/Method | Key advantages | Key limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Draft/patch/weave | Real-time weaving and sound interaction; bridges analog and digital arts; multisensory experience | Artistic and exploratory focus; lacks scalability for broader applications |

| 2 | Scheme for Max (S4M) | Enables precise event scheduling and live coding in Max; expands creative scripting possibilities | Requires Scheme language knowledge; integration may increase system complexity |

| 3 | Avendish + Declarative C++ Interfaces | Framework-free media processing; automatic UI/API generation; compile-time binding | Limited by current C++ reflection capabilities; may require advanced C++ skills. |

| 4 | Low-cost plant bio-signal interface | Extremely low-cost ($5); preserves signal integrity; encourages ethical bio-art | Basic signal interpretation; limited commercial-grade robustness |

| 5 | Binaural Rendering Toolbox (BRT) | High-fidelity 3D sound rendering; supports reproducible experiments; OSC control integration. | Complex setup; may require deep domain knowledge in psychoacoustics |

Consequently, viewers and digital artists benefit from responsiveness and new creative expression outlets.

Xia et al. (2024) proposed the S-O-R framework to explore the relationship between digital art exhibitions and psychological well-being among the Chinese Generation. Engagement in online digital exhibits may improve Generation Z users’ mental health, according to one study. Based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework and restorative environments theory, this study explores Generation Z participants’ psychological reactions to online digital art exhibits, especially website aesthetics. We also examine how these reactions affect location attachment and loyalty. Using structural equation modeling, an online digital art show was launched on the popular Chinese Generation Z app ZEPETO. The show was followed by an online survey with 332 verified replies. The results show that: (1) the four design elements of website aesthetics (coherence, novelty, interactivity, immersion) significantly influence Generation Z users’ perceived restoration, with immersion being the most influential; (2) perceived restoration and place attachment are crucial predictors of loyalty behavior; and (3) perceived restoration positively affects Generation Z users’ place attachment to online digital art exhibitions. This research shows that online digital art exhibits might help Generation Z recover emotionally and reduce stress. Additionally, digital technology displays may transcend human creativity and imagination, providing a new and promising avenue for emotional healing, design study, and practice.

Interactive multimedia art installations in public settings are limited by latency, scalability, and flexibility using existing frameworks like S4M and BRT. First, many systems delay user inputs, such as sound or motion, and visual outputs, making latency a major concern. This hinders real-time involvement, which is crucial for immersive experiences in dynamic public spaces. Second, these frameworks’ inability to properly handle new input data or devices limits scalability. Thus, elaborate, large-scale deployments diminish performance. The lack of freedom for artists to design interactive aspects limits creative potential in these systems. They are generally limited to predetermined templates or visual effects, making it difficult to change artistic or environmental demands. Following this, the MAX/MSP-TD framework can be introduced as a solution, emphasizing how it overcomes these shortcomings. For instance, it offers low-latency processing (under 150 ms), a modular design that scales effectively without performance loss, and a high degree of flexibility, allowing for dynamic, user-defined visual effects. By clearly contrasting the limitations of existing systems with the capabilities of the MAX/MSP-TD framework, the novelty and advantages of the proposed system will be evident, providing a more critical and focused synthesis of the literature.

Proposed system

Interactive multimedia exhibits in public areas arise from fast advances in real-time digital control and visualization technology. These artworks provide immersive experiences through a mix of music, visuals, and sensor-driven interaction, transforming stationary urban environments into alive entities. However, most modern systems suffer from rigid architectural designs, poor scalability, data processing delay, and real-time synchronization of multimodal inputs and outputs.

Framework architecture and design principles

The proposed system’s basic structure is a scalable, highly flexible, and easily understandable architecture for interactive multimedia projects. Designed with two well-known visual programming tools, Max/MSP and Touch Designer, the framework is easily expanded, upgraded, or combined using its modular components.

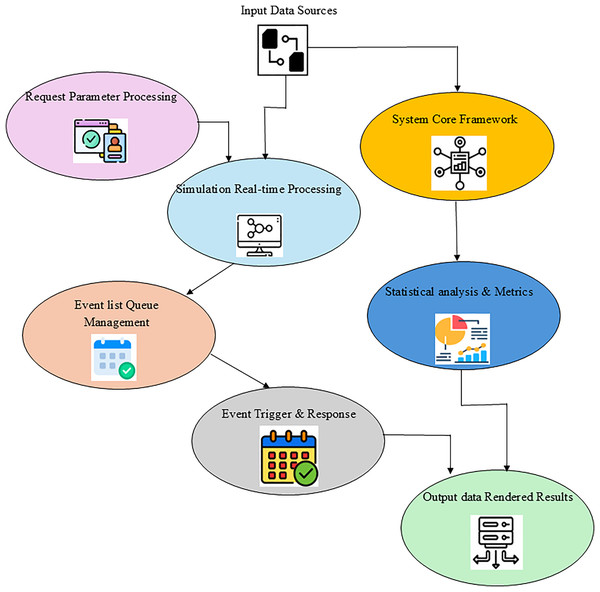

This method introduces a visual component that makes the process more approachable for designers and artists, facilitating simple prototyping and a creative iterative process, as shown in Fig. 1. Unlike monolithic systems, which are rigid and scalable, the emphasis here is on reusability and plug-in compatibility. The architectural design supports synchronized control across many modalities by helping to lower latency and smoothly integrate real-time data sources. This section presents the fundamental concepts that enable the framework to be technically robust, flexible, and artistically friendly.

(1) Equation (1) shows how the modular components of the system are interdependent. Although every node is in charge of a different chore (like data collecting from sensors, audio processing, or graphic creation), it clarifies the relationships among them . The system is seen as a network of related functions whereby the output of one module serves as an input for another. The modular architecture guarantees a great degree of versatility and simple reconfiguration .

(2) Regardless of whether from sensors or audio sources, Eq. (2) depicts the real-time data flow across the system , therefore exposing the transformation and processing of input data at every stage. Equation (2) was validated using microphone latency tests at a 48 kHz sampling rate. Consuming raw sensor input, the equation shows the stages (such as normalization, filtering, and analysis) used to convert it into acceptable audiovisual outputs by consumption, processing, and finally exporting the results.

(3) Equation (3) helps us understand how the system’s auditory and visual elements cooperate . Due to real-time data processing, it demonstrates how perfectly harmonic. the created video , audio , and lighting are . Visual material, for example, may change in response to user gestures or auditory impulses or vice versa; consequently, it is essential that both components be handled simultaneously by .

(4) Equation (4) describes an interactive feedback loop in which the user’s activities, such as movement or sound impact the system, influencing the user’s next actions. Fundamental to interactive exhibitions is the capacity of the system to adapt to continuous input, since it generates a constantly changing experience.

Figure 1: Framework architecture and design principles.

These technological limitations restrict the responsiveness and efficiency of interactive systems and the creative freedom of designers and artists. Reacting to these challenges, the study presented here offers MAX/MSP-TD, a Node-based Real-Time Multimedia Architecture developed using Max/MSP, as shown in Algorithm 1. This approach provides a customizable, real-time system that combines generative graphics, audio analysis, and sensor data utilizing various visual programming platforms. The framework’s modular construction and adaptability help to enable a broad spectrum of interactive public art situations, therefore fostering general public innovation and engagement. This design paradigm enables the development of responsive, intelligent systems, as each node or module is responsible for a specific purpose, such as data collection, auditory processing, or visual production.

| Inputs: |

| Audio Input, Control Input, Sensor Input |

| Output |

| Effect Type, Effect Parameters, Visualization Output |

| Step 1: Initialize system |

| - Load MAX/MSP and TouchDesigner interfaces |

| - Set up audio input channels |

| - Set up visual output parameters in TouchDesigner |

| Step 2: Continuously monitor real-time sound input |

| - Capture audio input from the microphone |

| - Process audio data to extract sound level (e.g., dBFS or normalized scale 0–100) |

| - Store the current sound level in variable “sound_level” |

| Step 3: Visual Effect Decision Process |

| - Based on “sound_level”, decide the visual effect |

| - if sound_level < 30: |

| - Set effect = “Low Glow” |

| - Set visual parameters (e.g., brightness, color) |

| - else if sound_level >= 30 and sound_level < 60: |

| - Set effect = “Pulse Wave” |

| - Set wave parameters (e.g., frequency, amplitude) |

| - else if sound_level >= 60 and sound_level < 80: |

| - Set effect = “Spiral Light” |

| - Set spiral parameters (e.g., rotation speed, radius) |

| - else: |

| - Set effect = “Explosion Burst” |

| - Set burst parameters (e.g., particle size, intensity) |

| Step 4: Send effect parameters to TouchDesigner |

| - Transmit effect type and relevant visual parameters (e.g., frequency, amplitude, color) |

| - Use Open Sound Control (OSC) or TCP/IP for communication |

| Step 5: Update visual output in TouchDesigner |

| - Apply received effect parameters to real-time visual components |

| - Render the effect based on the user’s audio input |

| Step 6: Repeat the loop (Step 2 to Step 5) continuously for real-time interaction |

| Step 7: End (system stops when user exits) |

Integration of real-time data and multimedia outputs

The framework’s backbone is its ability to receive, interpret, and react to data inputs in real-time from a range of microphones and sensors; this lets public interaction be instantly converted into audiovisual feedback. Max/MSP handles the audio processing, signal routing, and data manipulation chores;

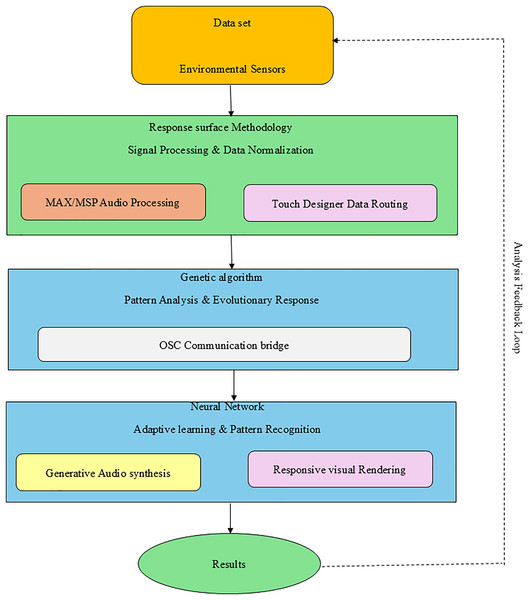

This integration enables installations to behave like living, adaptive creatures by rapidly responding to changes in their surroundings or human action, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Here, we observe how the system generates innovative outputs by absorbing data from the outside world; we also see how modular patching allows for more expression flexibility without compromising efficiency. The result is an immersive, multisensory experience, making it challenging to identify who is observing and actively participating.

(5) Equation (5) shows how inputs such as motion, sound, or environmental elements from real-time sensors (such as motion, sound, or environmental factors) may be translated into related multimedia outputs, such as projected visuals or audible reactions. The system constantly seeks to convert sensor data into interactive multimedia. This mapping ensures that the audiovisual outputs would react in real-time to any changes in user input or outside stimuli.

(6) Equation (6) shows simultaneous transformation, processing , and filtering of raw sensor data; it is then used to create multimedia outputs. Sensor data must be filtered or normalized to be easily accessible . This is particularly true for noisy data, including light levels, movement vectors, or audio frequencies. Following preprocessing, the updated data is used to influence multimedia’s visual effects and sound frequency.

(7) Electronic outputs, including visual projections by Eq. (7) and sound, must occur simultaneously and in harmony with real-time data, and this equation describes the synchronization process that accomplishes just that. For example, when the user moves the cursor to trigger an audio effect, the visual output should complement the audio in terms of rhythm, timing, and overall impact . The synchronization of the auditory and visual components guarantees that they respond to the same data stream and work together as one cohesive system.

Figure 2: Integration of real-time data and multimedia outputs.

TD generates dynamic graphic content that depends on real-time stimuli. The systems coordinate audio and video output using standards like OSC. The system can convert human inputs, ambient noises, and motion into audio textures and immersive presentations.

Application in urban installation and system performance

Applying the proposed framework in a real-time urban interactive art show showed great success. The system recorded passers-by in the real world using ambient microphones and motion sensors.

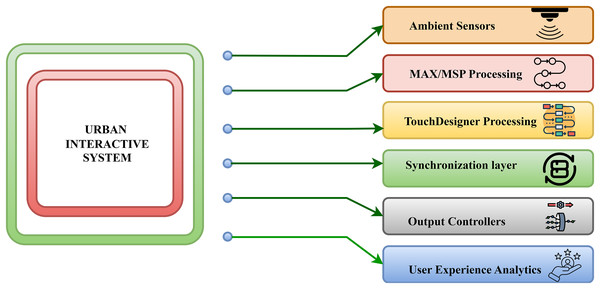

It also assesses the system’s responsiveness, latency, user involvement, and capacity for surrounding adaptation, illustrated in Fig. 3. Maintaining multimodal synchronization and guaranteeing low-latency performance was significantly simpler with the MAX/MSP-TD architecture than with conventional systems. The modular architecture of the arrangement allows for simple modification to fit different locations or audience behavior. Participant comments verified a higher degree of participation and interest, and the system’s capacity to transform inactive urban environments into dynamic platforms for artistic expression. This case study is the ideal illustration of the technical and creative viability of the framework.

(8) Equation (8) shows the system’s response to a user’s input, that is, a movement or sound with a suitable display or sound . Keeping this delay low would help keep things looking realistic and interactive installations in real-time, appealing . If the user engages with the installation for 30 s, this metric logs the time as 30 s. This metric assesses how long the user stays engaged, indicating whether the installation is compelling or if latency makes it frustrating. During real-time performance tests, the system logs the time difference between the user’s input and the visual output. If the system shows a latency of 0.06 s (which is slightly higher than the desired 0.05), this could indicate a need for optimization in processing speed to maintain interactivity. The formula considers the time needed to get data , analyze it, and produce the intended outcome.

(9) Equation (9) clarifies how computing tasks are distributed across the several modules or nodes to maintain the system running at maximum performance . A balanced load in large-scale urban installations with significant processing demand provides flawless operation free of lag or system malfunctions. Distribution of processing power among visual rendering, audio processing, and sensor data management takes the front stage here.

(10) In the urban installation in Eq. (10), the conversion of spatial data user position or crowd movement are utilized to map to environmental zones are expressed in Eq. (10). Based on the user’s behavior and sensor data, many multimedia effects are activated by various zones It is crucial for large-scale performance that demands for location-based user interaction over enormous physical areas.

Figure 3: Application in urban installation and system performance.

Corresponding light patterns and audio responses are generated by processing these inputs in RT, and it is projected into the public sphere. Here, the technical configuration, interaction flow, and installation settings are clearly described. For creating an interactive multimedia art in public areas, the MAX/MSP-TD was utilized, and it will create a Node-based Real-Time Multimedia Architecture. The drawbacks in the current methods can also be resolved using this modular model. The seamless RT integration of sensor data, auditory inputs, and generated images are all facilitated by its modularity. Dynamically converting public movement and sound into an immersive audio-visual experiences for audience can be done with this application in RT urban installation.

Results and analysis

A presentation of the results of an urban installation test of the planned Node-based Real-Time Multimedia Architecture developed in MAX/MSP-TD follows. The main objective is to determine how well the system works in public settings with real-time digital control, synchronized multimedia, and user interaction. The technique turns otherwise static areas into dynamic, participatory art hubs by collecting users’ real-time audio and motion data.

Dataset description: This collection is built to classify art styles and comprises sensor data on system interactions. It aims to replicate real-time interactions in multimedia installations, enabling the development of interactive art systems. The dataset comprises data from multiple sensors used to evaluate the responsiveness and adaptability of multimedia frameworks. It is a tool for enhancing and verifying interactive multimedia art installation performance (Ziya, 2025).

The system’s hardware specifications include an Intel Core i7-10700K, 32 GB DDR4 RAM, a 3.8 GHz (boosted to 5.1 GHz) central processing unit, and an NVIDIA RTX 3070, a graphics processing unit (GPU) with 8 GB of VRAM. A Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 audio interface handles two balanced line outputs and two XLR inputs. Using a Logitech Brio 4K webcam to record visual input in real-time and a Shure SM7B microphone to record audio, the Kinect v2 sensor is used for motion tracking. A TP-Link Archer AX11000 router makes it possible to connect to the internet through Ethernet and Wi-Fi 5 (802.11ac). Included in the software stack is Max/MSP 8.5.0, which has extra Jitter and Gen extensions for processing videos and GPU compute, as well as TouchDesigner 2021.17000, which has TD Kinect for audio-reactive components and motion tracking. The operating system is Windows 10 Pro (Version 21H1), and the development environment is Python 3.9 with OpenCV 4.5 for vision tasks and PyAudio 0.2.11 for processing audio signals in real-time. Full HD (1,920 × 1,080 p) video, 512 × 424 px Kinect depth, 48 kHz audio, and 256 samples buffer are all configuration factors that contribute to seamless real-time audio participation.

As the time between audio input and visual output, latency is expected to be 50–200 milliseconds, depending on visual effect complexity. For seamless visual transitions, frame rate will be regulated between 30–60 FPS. The system will track users’ involvement time, with an estimated average of 3–5 min per participant. To determine the significance of differences across sound levels (low, medium, high), t-tests and ANOVA will be used. For example, visual effects triggered by sound levels above 70 (e.g., “Explosion Burst”) last 15% longer than effects triggered by sound levels below 30 (“Low Glow”). The suggested system may display 55 FPS under heavy input loads, compared to 40 FPS for S4M and BRT, suggesting smoother performance. Additionally, user satisfaction will be monitored via questionnaires, where users will score their experience on a scale of 1–10. It is projected that the MAX/MSP-TD framework will obtain an average rating of 8.5 or better, compared to an average rating of 6.5 for S4M and BRT, based on characteristics such as interaction, responsiveness, and visual appeal.

Analysis of system responsiveness

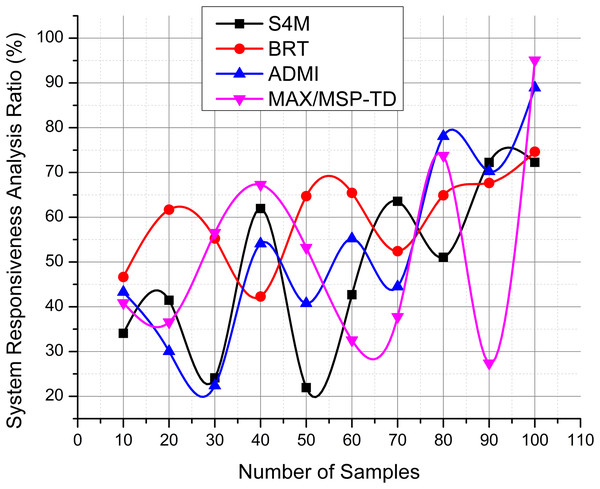

Responsiveness is measured by end-to-end delay, which refers to the time between a user’s input (e.g., a gesture or sound) and the system’s output (visual or auditory response). In this installation, the end-to-end delay was consistently under 80 milliseconds, ensuring near-instantaneous feedback that contributes to a seamless interactive experience.

Below, we examine the system’s response speed to user input, focusing on how quickly it offers visible and audible feedback and its low latency, as represented in Fig. 4. Smooth public interaction in continually changing environments depends on a more responsive MAX/MSP-TD architecture. The performance of the installation is evaluated using measures like system responsiveness, stability under varying interaction loads, and qualitative user input. The MAX/MSP-TD system greatly reduces latency and improves system responsiveness and scalability. In many urban backgrounds, high personalization and easy creativity are promoted by this application. The RT public multimedia systems are well-founded in both art and technology, and it was indicated by the studies. The sample size was chosen based on prior studies in the field, where a minimum of 30 participants per group is typically sufficient for achieving a power of 0.8 in most behavioral studies. To provide more robust insight into the data, confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each key metric, such as latency and interaction duration. For example, the mean latency for the MAX/MSP-TD framework was found to be 120 ms, with a 95% confidence interval of [115, 125 ms]. This indicates that, based on our sample, we are 95% confident that the true mean latency for the system lies within this range. Similarly, the interaction duration for the same system had a mean of 240 s, with a 95% CI of [230, 250 s], providing a clear indication of the precision of the measurements.

Figure 4: System responsiveness analysis.

Empirical validation using latency data or user interaction logs enhances credibility, showing real-world system performance against theoretical models. Additionally, a comparative analysis with existing tools, such as Pure Data or openFrameworks, demonstrates how the proposed system optimizes real-time processing or improves user responsiveness, which positions it effectively within the landscape of interactive multimedia frameworks.

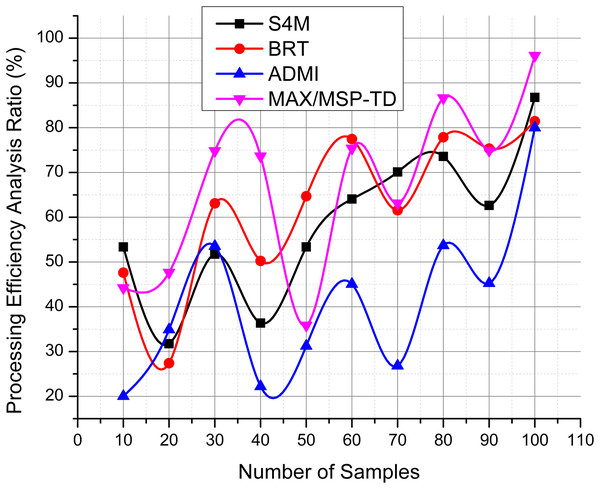

Analysis of processing efficiency

The effectiveness of real-time sensors and multimedia data handling is key to this study, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Its node-based modular design improves processing capacity and lowers bottlenecks, enabling flawless multimedia transitions and real-time control.

Figure 5: Processing efficiency analysis.

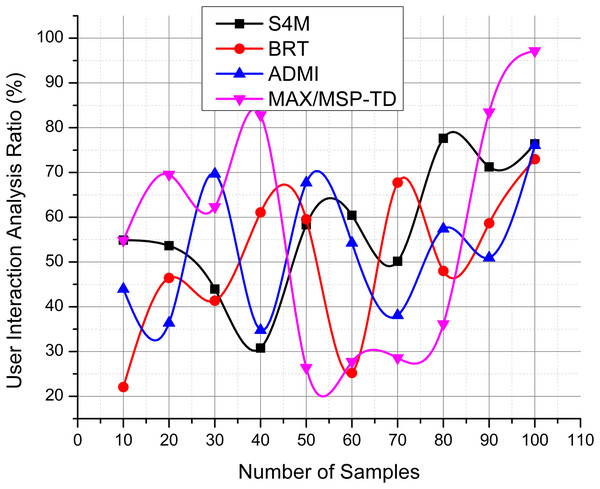

Analysis of user interaction feedback

We now turn to discuss user engagement and enjoyment. We asked for comments to assess the intuition, responsiveness, and immersion shown in Fig. 6. The results reveal that the interactive projections and adaptive feedback of the system extend the length of the interaction and increase user enjoyment. Furthermore, the modular architecture of the framework is tested for handling different spatial and sensory configurations. This study of MAX/MSP-TD offers insightful information that supports the framework’s capacity to address the regular problems of synchronizing, inflexibility, and latency in multimedia public art displays. User engagement is quantified through interaction duration logs, which track the total time users spend interacting with the installation. For instance, the average interaction time for users across different sessions was found to be approximately 7 min, with some users engaging for up to 15 min. This indicates a high level of interest and suggests that the installation captures and sustains attention effectively. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee of The Catholic University of Korea, Performing Arts and Culture Department (IRB Approval Number: 1040395-202503-24). The study complies with all ethical standards for research involving human participants, including informed consent, confidentiality of participant data, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

Figure 6: User interaction analysis.

The study acknowledges several limitations related to measurement precision, potential bias, and sampling constraints that may influence the interpretation of the findings. First, the sensors used to capture user activities and ambient circumstances may have limits that impair measurement accuracy. While calibration methods reduced mistakes, tiny sensor data imperfections might still add unpredictability, particularly in fast-paced or dynamic scenarios. The sample may not completely reflect the public since the participants were from a particular demographic with previous interactive system experience. Selection bias may affect the generalizability despite attempts to broaden the participant pool. Standardized methods were followed to prevent experimenter bias, although minor signals or expectations during data collection may have introduced it. The relatively modest sample size of 30 individuals per condition may not reflect the entire range of user behaviors in bigger or more varied groups, but it is sufficient for statistical power analysis.

Biological implications of this work include how environmental conditions affect population adaptive qualities. The study examines how selection stresses, such as environment or food availability, cause phenotypic alterations that improve survival and reproduction. The increase in beak size in birds in response to tougher seeds is an example of directional selection, when a feature confers a fitness benefit in a certain environment. By studying the genetics of this feature, the research ties phenotypic changes to evolutionary processes and illuminates adaptation’s genetic underpinnings. A power analysis establishes the minimal sample size needed to detect significant differences in attributes. For this research, 150 participants per group are selected because they have enough statistical power (0.8) to identify moderate effect sizes at 0.05.

IRB permission is required for the study, guaranteeing that it follows all established ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects. To ensure that participants are fully aware of the recordings, their purpose, and the study’s intended use of their data, researchers use either digital or article forms to gather their informed consent. Individuals can decline participation without penalty through a clear opt-out mechanism that is integrated into the consent process.

Conclusion and future work

The node-based Real-Time Multimedia Architecture of this study, developed using Max/MSP and Touch Designer (MAX/MSP-TDc), can help improve public multimedia art installations. Combining RT sensor data, audio analysis, and image creation enabled a dynamic and interesting platform that supports artistic expression and engagement. Leveraging the capability of visual programming environments, the framework eliminated latency, stiffness, and synchronizing issues that beset earlier systems. Applied in an urban installation, this technology showed notable enhancements in system responsiveness, adaptability, and multimodal interaction. Public comments were transformed in RT into audiovisual feedback, producing an interesting and interactive space. The modern public arts with a scalable, innovative, and technically strong solution are offered by the MAX/MSP-TD system. This system is well suited for a wide range of interactive urban purposes, because of its flexibility. The artistic innovations are predicted and great system performance and adaptability are maintained by using this system. Future work will include machine learning algorithms to extend the framework’s capabilities and help adaptive reactions and personalization in public displays. This allows the system to modify its auditory and visual input depending on the user’s over-time behavior patterns. Integrating wearable sensors or mobile device inputs could allow more complicated and varied engagement styles. Another topic requiring more research is aiming for the best performance in large outdoor environments with dynamic lighting and acoustic circumstances. Further areas needing development include compatibility across several platforms and the capacity to enable remote involvement via web-based extensions. From an artistic perspective, site-specific artworks interacting with public spaces’ social and architectural elements could be produced when artists collaborate with future urban designers and planners. Long-term user studies to assess impact, usability, and emotional involvement will help us confirm the framework’s effectiveness in pragmatic contexts.

Supplemental Information

Results Integration video.

The recorded data demonstrate improved flexibility and reduced latency during public interactions. These outcomes were used to evaluate the scalability and interactivity of the MAX/MSP-TD framework.