MAFF inhibits angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer by suppressing YAP1 nuclear translocation

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Emanuela Felley-Bosco

- Subject Areas

- Cell Biology, Oncology, Medical Genetics

- Keywords

- NSCLC, MAFF, YAP1, Angiogenesis

- Copyright

- © 2025 Ding et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. MAFF inhibits angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer by suppressing YAP1 nuclear translocation. PeerJ 13:e20395 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20395

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the roles of MAFF and Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) in regulating angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and to explore the mechanism through which MAFF inhibits angiogenesis by suppressing YAP1 nuclear translocation.

Methods

Bioinformatics analysis was used to assess MAFF expression and its associated regulatory pathways. Clinical samples from NSCLC patients were analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) to evaluate the correlation between MAFF expression and microvessel density (MVD). Cellular experiments were conducted to examine the effects of MAFF overexpression on proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis. Western blot (WB) and immunofluorescence (IF) analyses were performed to assess the expression of YAP1, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). Tumor growth suppression was evaluated using nude mouse xenograft models.

Results

MAFF was significantly downregulated in NSCLC tissues and correlated with advanced T stage and higher MVD. Overexpression of MAFF inhibited NSCLC cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis, and downregulated the expression of YAP1, VEGF, and CTGF. IF confirmed that MAFF suppressed nuclear translocation of YAP1. In vivo, MAFF overexpression reduced tumor volume and weight, which was accompanied by inhibition of the YAP1 signaling pathway.

Conclusion

MAFF suppresses angiogenesis in NSCLC by blocking YAP1 nuclear translocation and downregulating VEGF and CTGF, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the most lethal malignancy worldwide, with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) accounting for approximately 80–85% of all cases (Pirlog et al., 2022). NSCLC primarily consists of two major histological subtypes: Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) (Herbst, Morgensztern & Boshoff, 2018). LUAD represents the most prevalent subtype, and its incidence has been increasing annually (Denisenko, Budkevich & Zhivotovsky, 2018). Early-stage NSCLC often presents with nonspecific symptoms, leading to frequent delays in diagnosis; consequently, the majority of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages (Molina et al., 2009). Although significant progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC, the 5-year survival rate for patients with advanced disease remains below 20% (Li et al., 2023). Therefore, investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying NSCLC and identifying novel therapeutic targets are of critical importance.

NSCLC is characterized by high vascularity, and angiogenesis plays a pivotal role in its development and progression. Anti-angiogenic therapies have demonstrated considerable clinical potential, particularly in combination with chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. For example, anti-angiogenic agents can enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors by normalizing the tumor vasculature and reducing immunosuppressive components within the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Song et al., 2020). Preclinical studies have shown that combining anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies with VEGFR2 inhibitors significantly improves survival in murine lung cancer models (Zhao et al., 2019). Several anti-angiogenic drugs, including anti-VEGFA antibodies, anti-VEGFR2 antibodies, and small-molecule VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), are currently under clinical evaluation. However, these treatments are associated with limitations such as innate or acquired resistance and an elevated risk of bleeding events (Elice & Rodeghiero, 2012). Thus, the discovery of novel molecular regulators of angiogenesis and the elucidation of their mechanisms of action represent urgent challenges in both basic and clinical research.

The MAF proteins (MAFs) belong to the basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) family of transcription factors and are subdivided into two groups: large MAFs (including MAFA, MAFB, and c-MAF) and small MAFs (such as MAFF, MAFG, and MAFK) (Yoshida & Yasuda, 2002). Large MAF proteins contain an N-terminal transactivation domain and can form homodimers to regulate target genes. In contrast, small MAF proteins lack a transactivation domain and must heterodimerize with Cap‘n’collar (CNC) transcription factors (such as NRF1 or NRF2) or BACH proteins. These complexes bind to MAF recognition element (MARE) or antioxidant response element (ARE) sequences to modulate the expression of genes involved in oxidative stress and inflammatory responses (Oyake et al., 1996; Itoh et al., 1997). Among them, MAFF, a small MAF protein, is implicated in diverse physiological and pathological processes—including hematopoiesis, cellular stress response, and carcinogenesis. Nevertheless, the functional crosstalk between MAF family proteins and the Hippo/YAP pathway in the context of angiogenesis remains largely unexplored.

In recent years, YAP1, a core effector of the Hippo signaling pathway, has attracted increasing attention due to its crucial role in tumorigenesis. The Hippo pathway is essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis and regulating organ size by controlling cell proliferation, apoptosis, and stem cell maintenance (Zhao et al., 2007). When the Hippo pathway is inactivated, YAP1 becomes dephosphorylated and translocates into the nucleus, where it associates with transcription factors of the TEA domain (TEAD) family (TEAD1–4). This complex activates the transcription of multiple pro-tumorigenic genes, including connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61), and amphiregulin (AREG) (Zhao et al., 2008; Lamar et al., 2012). YAP1 promotes angiogenesis through diverse mechanisms. In NSCLC, YAP1 enhances cancer stem cell (CSC) self-renewal and vasculogenic mimicry by interacting with OCT4 and activating SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2) expression (Bora-Singhal et al., 2015). In breast cancer, miR-205 promotes VEGF-independent angiogenesis in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) by regulating YAP1. Modulating YAP1 expression significantly influences CAF migration, invasion, and tube-forming ability—a process dependent on STAT3 signaling rather than the VEGF pathway (Du et al., 2017). Additionally, RNA methylation modifications (such as m6A) within the Hippo/YAP pathway are closely linked to angiogenic capacity and YAP1-driven malignant progression. For instance, ALKBH5 inhibits angiogenesis in NSCLC by regulating YAP1 m6A modification (Han et al., 2023). These findings illustrate the multifaceted role of YAP1 in coordinating angiogenesis through various molecular and epigenetic mechanisms across cancer types.

The clinical translation of YAP1 inhibitors faces inherent challenges, including pathway compensatory mechanisms (e.g., YAP1 escape via the EGFR/MAPK pathway) which limit the efficacy of monotherapies (Song et al., 2015). Moreover, inhibiting the YAP1–TEAD interaction may disrupt normal biological functions—such as cardiac development—and cause tissue toxicity (Zhao et al., 2007). Existing YAP1 inhibitors (e.g., verteporfin) suffer from pharmacological limitations, including photosensitivity, poor blood–brain barrier penetration, and off-target effects (Song et al., 2015, 2018). In this context, we sought to determine whether MAFF regulates YAP1 activity or expression, thereby influencing the expression of angiogenesis-related genes and ultimately modulating tumor angiogenesis and growth. Through systematic in vitro and in vivo experiments, we aim to provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of angiogenesis in NSCLC and a theoretical foundation for developing more effective anti-angiogenic strategies.

Materials and Methods

Transcriptome analysis

Bioinformatic analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.0). To evaluate the pan-cancer expression profile of MAFF, we utilized the TIMER 2.0 web server. For LUAD, paired RNA-seq data and corresponding clinical information were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. After removing samples with missing or incomplete clinical annotations, a total of 58 paired tumor and adjacent normal tissues were retained for subsequent analysis. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was carried out with the clusterProfiler R package to identify signaling pathways significantly associated with MAFF expression levels. Additionally, single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA), implemented through the GSVA package, was employed to estimate the relative abundance of tumor-infiltrating immune cell subsets in each sample.

Single-cell RNA sequencing data analysis

The GSE198099 dataset was acquired from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, which included two LUAD samples and two adjacent non-tumor tissue samples. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data were processed using the Seurat package to ensure reproducibility. Stringent quality control criteria were applied as follows: (1) Gene expression cutoff: only cells expressing at least 200 genes were retained; (2) UMI Threshold: cells with more than 500 UMI counts were included; (3) Mitochondrial gene content: cells with mitochondrial gene expression exceeding 10% were excluded; (4) Hemoglobin gene expression: cells exhibiting hemoglobin gene expression above 0.1% were removed. After preprocessing, the datasets were integrated and normalized using Harmony to correct for batch effects. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed for dimensionality reduction and identification of highly variable genes. Subsequently, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) was applied for non-linear dimensionality reduction to visualize cell clusters. Finally, gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was performed within TCGA cohort to assess prognostic associations, providing further clinical insights.

IHC

A total of 56 paracancerous normal tissue specimens and 77 LUAD samples were collected from Baise People’s Hospital. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of LUAD; (2) no previous history of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapy; (3) absence of severe comorbidities or other synchronous malignancies; (4) completion of standard adjuvant therapy following surgical resection; and (5) availability of comprehensive clinicopathological records. The cohort consisted of 31 male and 46 female patients, with ages ranging from 40 to 77 years (44 patients <60 years and 33 patients ≥60 years). Based on pathological staging, the cases were distributed as follows: 50 stage I, 14 stage II, 9 stage III, and 4 stage IV. Lymph node metastasis was identified in 16 cases, and distant metastasis was present in six cases.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants using institutionally approved consent documents. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Baise People’s Hospital (Approval No. KY2023111726) in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections from the collected specimens were subjected to IHC staining using specific antibodies against MAFF (12771-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA; dilution 1:200) and YAP1 (A19134, Abclonal, Woburn, MA, SA; dilution 1:200). Protein expression levels were assessed using the Immunoreactive Score (IRS) system, which incorporates both staining intensity and the proportion of positive cells. Staining intensity was graded as follows: 0 (none), 1 (light yellow), 2 (brownish yellow), and 3 (tan). The percentage of positive cells was scored as: 0 (0–5%), 1 (6–25%), 2 (26–50%), 3 (51–75%), and 4 (>75%). The final IRS was calculated by multiplying the intensity and positivity scores, with a composite score of <3 considered indicative of negative expression.

Cell culture, lentiviral vector

This study utilized the following cell lines: immortalized human normal bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B), immortalized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), human embryonic kidney 293T cells, and NSCLC cell lines (A549 and H1299). All cell lines were purchased from Wuhan Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). For stable overexpression of MAFF, a lentiviral vector (pReceiver-Lv201) carrying the MAFF sequence was obtained from iGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Columbia, MS, USA).

In vitro functional studies

Cell viability was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the colony formation assay, stably transfected cells were cultured for 7 days to allow colony formation. The resulting colonies were then fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for visualization and quantification. To evaluate cell migration, a wound healing assay was performed: stably transfected cells were seeded in six-well plates and grown to 90% confluence. A uniform scratch was introduced into the monolayer using a sterile pipette tip. After 24 h of incubation, wound closure was assessed following fixation and staining with 0.1% crystal violet. Cell invasion was examined using Transwell invasion chambers coated with Matrigel. For the angiogenesis assay, HUVECs were seeded onto Matrigel-coated 96-well plates and tube formation was observed and imaged after an appropriate incubation period. All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated independently three times.

In vivo tumorigenicity assay

Eight female BALB/c nude mice (aged 4–5 weeks, weighing 15–17 g) were obtained from Beijing Vitong Lihua Animal Co., Ltd. All animals were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at Youjiang Nationality Medical University. Mice were kept in individually ventilated cages with controlled temperature (18–25 °C), humidity (50–70%), and a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle. Each cage contained four mice, provided with sterilized corn-cob bedding (changed twice weekly), autoclaved standard rodent diet, and sterile water ad libitum. Environmental enrichment was supplied in the form of paper tube shelters. To minimize cage-related confounding effects, animals from different experimental groups were systematically distributed across the housing rack. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of Youjiang Nationality Medical University (Approval No. 2024122001).

A total of 2 × 106 transfected A549 cells suspended in 100 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were subcutaneously injected into the axillary region of anesthetized mice. The mice were randomly assigned to control or experimental groups using a computer-generated randomization sequence, with four mice per group. Tumor growth was monitored over 18 days, and tumor diameters were measured every 48 h using a caliper. All measurements were performed by investigators blinded to group assignments. Strict humane endpoints were applied throughout the study: animals exhibiting moribund status (e.g., inability to access food or water), severe mobility impairment, a tumor diameter exceeding 20 mm, or ulceration affecting >15% of the tumor surface area were euthanized immediately. All remaining mice were euthanized at the experimental endpoint (18 days post-injection).

Euthanasia was performed by placing mice in an induction chamber and administering 5% isoflurane mixed with oxygen (flow rate: 1 L/min) until respiratory arrest occurred. Cervical dislocation was then promptly carried out to ensure death. Absence of pupil reflex and cardiac activity was confirmed prior to the excision of xenograft tumors for subsequent analysis.

Statistical analysis

Bioinformatic analyses were conducted using the R programming language (version 4.3.0). Statistical analyses for cellular and animal experiments were performed with GraphPad Prism® (version 9.5.0). For continuous variables following a normal distribution (assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test) with homogeneity of variance (evaluated by Levene’s test), comparisons between two groups were made using the unpaired Student’s t-test. For data that did not meet normality assumptions, the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied. Categorical variables were analyzed using the following tests: the Chi-square test was used when all expected frequencies were greater than 5 and the total sample size was ≥40; Yates’ correction for continuity was applied when any expected frequency was between 1 and 5 and the sample size was ≥40; and Fisher’s exact test was employed when any expected frequency was less than 1 or the total sample size was less than 40. Additional details regarding statistical methods are provided in the Supplemental Materials.

Results

Differential expression analysis of MAFF in cancer

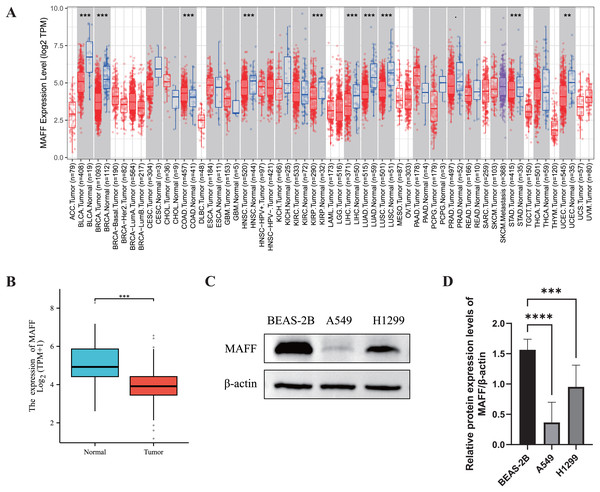

We systematically evaluated the expression pattern of MAFF across multiple cancer types using the TIMER2.0 database. The results revealed significant differential expression of MAFF in various cancers (Fig. 1A). Compared with normal tissues, MAFF was consistently downregulated in numerous malignancies, including bladder cancer, breast cancer, cervical cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, kidney chromophobe carcinoma, kidney renal pelvis carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, LUAD, LUSC, prostate cancer, and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma, with all differences reaching statistical significance. These findings suggest that MAFF may function as a tumor suppressor in the development and progression of these cancers. To further validate these observations, we obtained paired transcriptomic data from TCGA for LUAD and evaluated MAFF expression using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The results confirmed that MAFF expression was significantly lower in LUAD tissues compared to adjacent normal samples (Fig. 1B), which was consistent with the TIMER2.0 findings.

Figure 1: Differential expression analysis of MAFF in cancer.

(A) The pan-cancer differential expression analysis of MAFF in the TIMER2.0 database demonstrated statistically significant differences compared to normal tissues, as analyzed by the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test, ****P < 0. 0001, ***P < 0.001. (B) Statistical significance was analyzed using the paired T-test comparing tumor tissues with their matched adjacent normal counterparts, which showed that MAFF was significantly downregulated in tumor tissues, ***P < 0.001. (C) Expression levels of MAFF across different cell lines. (D) Compared to normal cell lines, statistical significance was analyzed using ordinary one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, MAFF expression was significantly lower in the lung cancer cell lines A549 and H1299, with ****P < 0.0001 and ***P < 0.001.Furthermore, we examined MAFF expression at the protein level using WB analysis in different cell types. The results showed that MAFF expression was significantly reduced in NSCLC cell lines (A549 and H1299) compared to immortalized human normal BEAS-2B cells (Figs. 1C and 1D), supporting a potential tumor-suppressive role of MAFF in NSCLC.

In summary, MAFF is significantly downregulated across a wide spectrum of cancers, as consistently demonstrated by both bioinformatic analyses and experimental validation. These results imply that MAFF may act as a tumor suppressor in various malignancies, underscoring the need for further functional studies to elucidate its mechanistic roles in cancer biology.

GSEA enrichment analysis and immune infiltration analysis

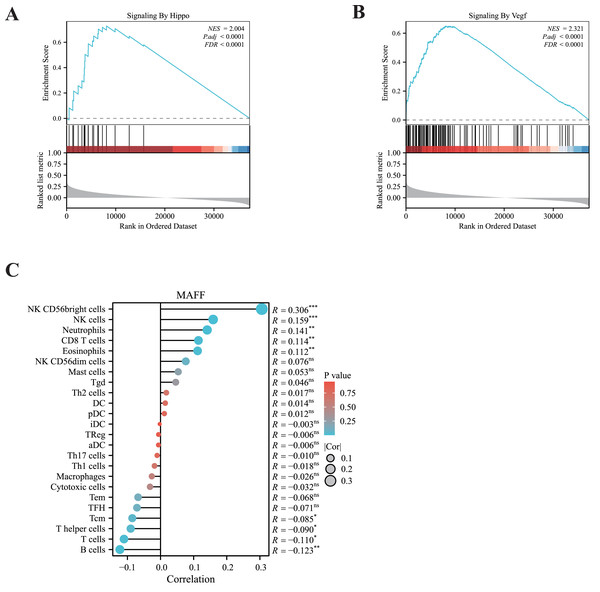

To elucidate the potential signaling pathways associated with MAFF in LUAD, we performed GSEA. The results revealed significant enrichment of MAFF-related genes in the VEGFA signaling pathway and the Hippo signaling pathway (Figs. 2A, 2B), suggesting a functional involvement of MAFF in these processes within NSCLC. The crosstalk between these pathways may offer important mechanistic insights into the biological roles of MAFF.

Figure 2: GSEA enrichment analysis and immune infiltration analysis.

(A) MAFF is closely related to the HIPPO pathway. Statistical significance was analyzed using the normalized enrichment score (NES), Benjamini-Hochberg correction, and false discovery rate (FDR), NES = 2.004, P.adj < 0.0001, and FDR < 0.0001. (B) MAFF is closely related to the VEGF pathway, NES = 2. 321, P.adj < 0.0001, and FDR < 0.0001. (C) MAFF expression levels are associated with the infiltration of various immune cells, with statistical significance analyzed using Spearman analysis, ns not significant, *** P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.Additionally, we employed ssGSEA to examine the correlation between MAFF expression and immune cell infiltration. Our analysis showed a significant positive association between MAFF expression and the abundance of several immune cell types, including natural killer (NK) cells, neutrophils, CD8+ T cells, and eosinophils (Fig. 2C). These findings suggest that MAFF may promote the infiltration of immune cells into the tumor microenvironment, potentially enhancing antitumor immunity. This immunomodulatory function could contribute to remodeling the tumor microenvironment and may inform future combination strategies incorporating immunotherapy.

Single-cell RNA sequencing and functional analysis

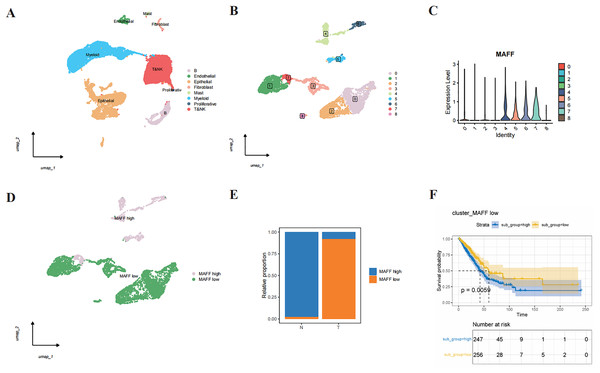

Through single-cell RNA sequencing analysis, we successfully identified major cell types within the tumor microenvironment, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, T cells, NK cells, B cells, mast cells, fibroblasts, and myeloid cells (Fig. 3A). Further subclustering of epithelial cells revealed transcriptionally distinct subpopulations (Fig. 3B). Violin plots illustrated the relative expression levels of MAFF across these subpopulations (Fig. 3C). Based on expression patterns, we categorized the cells into two groups: low MAFF expression (populations 0, 1, 2, 3, and 8) and high MAFF expression (populations 4, 5, 6, and 7) (Fig. 3D). Notably, tumor tissues exhibited a significant reduction in the proportion of MAFF-high cell populations compared to normal tissues (Fig. 3E), implicating MAFF as a potential modulator of tumor progression.

Figure 3: Single-cell RNA sequencing and functional analysis.

(A) A cell clustering diagram of the single-cell dataset. (B) A secondary clustering diagram of epithelial cells. (C) A violin plot showing the expression distribution of MAFF across different epithelial cell subpopulations. (D) Based on the expression distribution of MAFF, epithelial cell subpopulations 4, 5, 6, and 7 are defined as MAFF high-expression cell groups, while subpopulations 0, 1, 2, 3, and 8 are defined as MAFF low-expression cell groups. (E) The proportion of MAFF low-expression cell groups in normal epithelial cells and tumor epithelial cells, with a significant increase observed in tumor epithelial cells. (F) GSVA prognostic analysis of MAFF low-expression cell groups, showing that the high-scoring group has worse prognosis P = 0.0059.To further explore the functional significance of MAFF-negative cell populations, we performed GSVA using transcriptomic data from the TCGA cohort. The results indicated that higher GSVA scores for MAFF-negative populations were strongly correlated with worse patient prognosis (Fig. 3F). These findings suggest that MAFF may act as a tumor suppressor in the tumor microenvironment, and its loss could activate oncogenic signaling pathways, thereby facilitating tumor growth and progression. Together, these results underscore the multifaceted role of MAFF in cancer biology and support further investigation into its therapeutic potential.

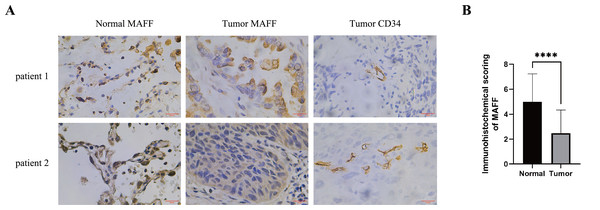

The relationship between MAFF expression in NSCLC tissues and clinical pathological characteristics

IHC staining was performed on pathological sections from 56 paracancerous normal tissues and 77 NSCLC samples obtained from Baise People’s Hospital. The results demonstrated that MAFF expression was significantly downregulated in NSCLC tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues (Figs. 4A, 4B). To evaluate the clinical relevance of MAFF expression, we conducted a detailed correlation analysis between MAFF levels and clinicopathological parameters in this cohort (Table 1). The analysis indicated that MAFF expression was not significantly associated with patient age, gender, pathological stage, lymph node metastasis, or distant metastasis. However, a statistically significant correlation was observed between reduced MAFF expression and advanced clinical T-stage, as well as higher microvessel density MVD. These findings suggest that decreased MAFF expression is closely linked to enhanced tumor angiogenesis, implicating a potential role for MAFF in regulating the tumor microenvironment and modulating angiogenic processes during NSCLC progression.

Figure 4: The relationship between MAFF expression in NSCLC tissues and clinical pathological characteristics.

(A) Immunostaining for MAFF and CD34 under high magnification, scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Compared to normal tissue, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test. ****P < 0.0001.| Characteristics | Positive | Negative | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 31 | 46 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.483 | ||

| Male | 11 (14.3%) | 20 (26%) | |

| Female | 20 (26%) | 26 (33.8%) | |

| Age, n (%) | 0.737 | ||

| <60 | 17 (22.1%) | 27 (35.1%) | |

| ≥60 | 14 (18.2%) | 19 (24.7%) | |

| Differentiation, n (%) | 0.447 | ||

| Low | 2 (2.6%) | 6 (7.8%) | |

| Moderate | 29 (37.7%) | 39 (50.6%) | |

| High | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| T classification, n (%) | 0.046 | ||

| I | 21 (27.3%) | 29 (37.7%) | |

| II | 4 (5.2%) | 10 (13%) | |

| III | 2 (2.6%) | 7 (9.1%) | |

| IV | 4 (5.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| N classification, n (%) | 0.162 | ||

| No | 27 (35.1%) | 34 (44.2%) | |

| Yes | 4 (5.2%) | 12 (15.6%) | |

| M classification, n (%) | 0.347 | ||

| No | 27 (35.1%) | 44 (57.1%) | |

| Yes | 4 (5.2%) | 2 (2.6%) | |

| MVD, median (IQR) | 7.8 (6.4, 9.4) | 9.9 (7.65, 11.35) | 0.043 |

MAFF inhibits NSCLC cell behavior in vitro

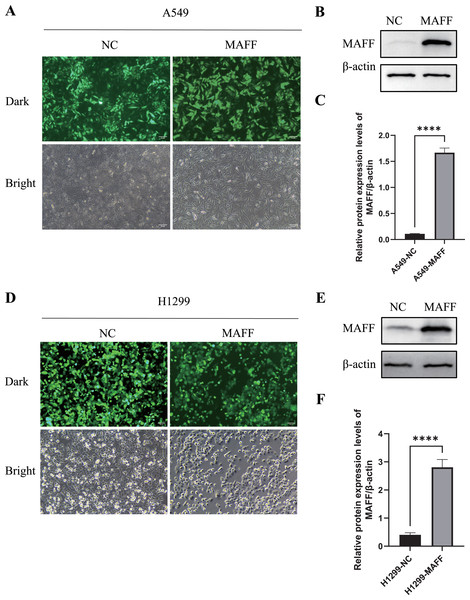

To investigate the biological function of MAFF in NSCLC cells, we established stable MAFF-overexpressing cell lines in A549 and H1299 cells through lentiviral infection followed by selection with puromycin. Fluorescence microscopy confirmed successful infection and the presence of a stably expressing cell population (Figs. 5A, 5D). WB analysis further verified that MAFF expression was significantly upregulated in transfected cells compared to control groups (Figs. 5B, 5C, 5E, 5F).

Figure 5: Construction of a stable cell line expressing MAFF.

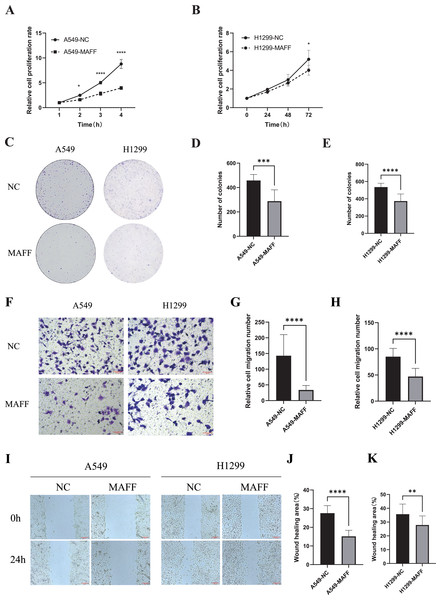

(A) A549 stable cell line fluorescence characteristics, scale bar: 20 μm. (B) MAFF protein expression levels in A549 stable cell line. (C) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ****P < 0.0001. (D) H129 9 stable cell line fluorescence characteristics, scale bar: 20 μm. (E) MAFF protein expression levels in A549 stable cell line. (F) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ****P < 0.0001.Functional assays were performed to assess the effects of MAFF overexpression. CCK-8 assays, conducted with three independent biological replicates each including at least three technical repeats, showed that MAFF significantly inhibited the proliferation of both A549 and H1299 cells (Figs. 6A, 6B). Similarly, plate colony formation assays demonstrated a marked suppression of clonogenic ability upon MAFF overexpression (Figs. 6C–6E). Transwell invasion assays revealed that MAFF significantly reduced invasive capacity (Figs. 6F–6H), and wound healing assays indicated impaired cell migration in MAFF-expressing cells (Figs. 6I–6K). All functional experiments were independently repeated three times, with each replicate comprising a minimum of three technical replicates for statistical analysis.

Figure 6: MAFF inhibits NSCLC cell behavior in vitro.

(A) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using two-way ANOVA and Sidak multiple comparisons, ****P < 0.0001, *P < 0.05. (B) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using two-way ANOVA and Sidak multiple comparisons, *P < 0.05. (C) Clonal formation analysis diagram, scale bar: 20 μm. (D) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ***P < 0.001. (E) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ****P < 0.0001. (F) Transwell invasion situation under high magnification, scale bar: 20 μm. (G) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ****P < 0.0001. (H) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ****P < 0.0001. (I) Healing situation of the scratch assay in the stable transfected cell line, scale bar: 200 μm. (J) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ****P < 0.0001. (K) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, **P < 0.01.MAFF inhibits HUVEC angiogenesis in vitro

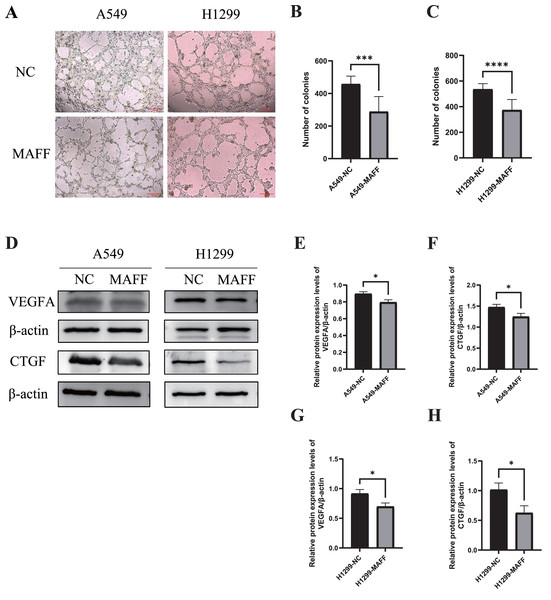

When A549 and H1299 stable cell lines reached 70–80% confluence, the complete culture medium was aspirated, and the cells were gently washed with phosphate-buffered saline PBS. Serum-free basal medium was then added, and the cells were incubated for 24 h to prepare conditioned medium for the angiogenesis assay. Subsequently, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) at 70–80% confluence were trypsinized, resuspended in the conditioned medium, and seeded at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well into 96-well plates pre-coated with Matrigel. After 8 h of incubation under standard culture conditions, tube formation was assessed and photographed for quantitative analysis. The experiment was repeated three times independently with at least three technical replicates per condition.

The results demonstrated that overexpression of MAFF significantly inhibited the tube-forming ability of HUVECs (Figs. 7A, 7B). Furthermore, WB analysis confirmed that MAFF downregulated the expression of key angiogenic factors, including VEGFA and CTGF (Figs. 7D–7H).

Figure 7: MAFF inhibits HUVEC angiogenesis in vitro.

(A) Tube formation of HUVEC co-cultured with the supernatant of the stable transfected cell line culture medium. (B) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited the tube-forming ability of A549, ***P < 0.001. (C) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited the tube-forming ability of H1299, ***P < 0.001. (D) MAFF suppresses the protein expression of angiogenesis-related factors, including VEGFA and CTGF. (E) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited VEGFA expression in A549 cells, *P < 0.05. (F) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited CTGF expression in A549 cells, *P < 0.05. (G) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, which showed that MAFF significantly decreased VEGFA expression in H1299 cells, *P < 0.05. (H) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, which showed that MAFF significantly decreased CTGF expression in H1299 cells, *P < 0.05.MAFF inhibits YAP1 expression and its nuclear translocation

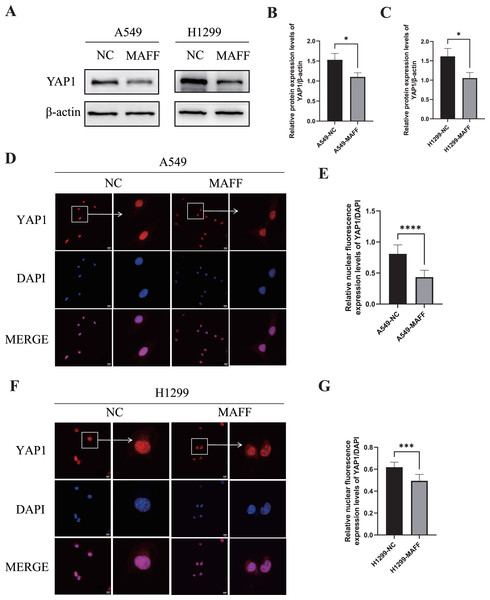

WB analysis was performed to examine the expression levels of YAP1 and its downstream angiogenesis-related factors, while IF was used to evaluate YAP1 nuclear translocation. All experiments were independently repeated three times, with each replicate including at least three technical repeats. WB results demonstrated that MAFF overexpression significantly downregulated YAP1 expression (Figs. 8A–8C). Consistent with this, IF analysis revealed a marked reduction in YAP1 nuclear translocation upon MAFF treatment (Figs. 8D–8F).

Figure 8: MAFF inhibits YAP1 expression and nuclear translocation.

(A) MAFF inhibits the expression of YAP1. (B) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, *P < 0.05. (C) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, *P < 0.05. (D) Nuclear expression of YAP1 in A549 stable transfected cell line. (E) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ****P < 0.0001. (F) Nuclear expression of YAP1 in H1299 stable transfected cell line. (G) Compared with the control group, statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired T-test, ***P < 0.001.Inhibition of tumor cell growth by MAFF in vivo

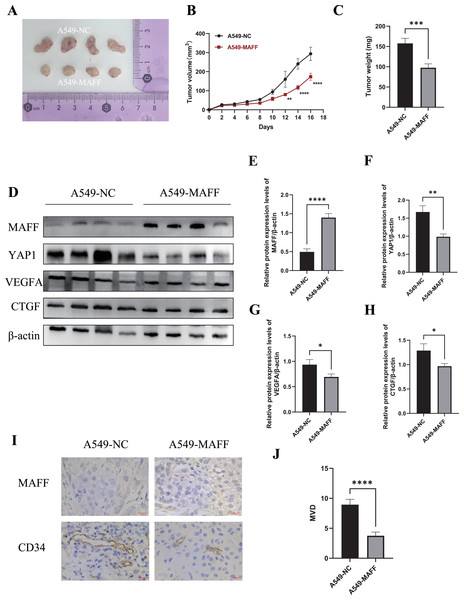

To evaluate the antitumor effects of MAFF in vivo, a xenograft tumor model was established using A549 control cells and MAFF-overexpressing cells. A total of 2 × 106 cells suspended in 100 μl of PBS were subcutaneously injected into the axilla of female Balb/c nude mice (n = 4 per group). Tumor volume was measured every two days using a caliper, and growth curves were generated accordingly. All mice were euthanized 18 days after inoculation, and the tumors were excised and weighed (Figs. 9A–9C). The results demonstrated that MAFF overexpression significantly inhibited tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 9: Inhibition of tumor cell growth by MAFF in vivo.

(A) Tumor formation status, scar bar: 20 μm. (B) Variation in tumor volume growth, statistical significance was analyzed using two-way ANOVA compared to the control group, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited tumor volume in vivo, ****P < 0.0001, **P < 0.01. (C) Tumor weight analysis using unpaired t-test compared to the control group, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited tumor weight in vivo, ***P < 0.001. (D) Western Blot results of tumor tissue. (E) Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t-test compared to the control group, which showed that stably transfected cells significantly overexpressed MAFF in tumors, ****P < 0.0001. (F) Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t-test compared to the control group, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited YAP1 expression in vivo **P < 0.01. (G) Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t-test compared to the control group, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited VEGFA expression in vivo, *P < 0.05. (H) Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t-test compared to the control group, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited CTGF expression in vivo, *P < 0.05. (I) Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor tissue. (J) Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t-test compared to the control group, which showed that MAFF significantly inhibited MVD in tumors. ****P < 0.0001. The asterisks represent the following significance levels: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.Tumor tissues were collected for subsequent protein analysis. WBting was performed to examine the expression of YAP1 and its downstream factors (Fig. 9E). The results indicated that MAFF downregulated the protein levels of YAP1, CTGF, and VEGFA (Fig. 9F). Additionally, paraffin-embedded tumor sections were subjected to immunohistochemical staining to evaluate MVD. The findings revealed that MAFF significantly reduced MVD compared with the control group (Figs. 9G, 9H). All experiments involving tissue analysis were repeated independently three times to ensure reproducibility.

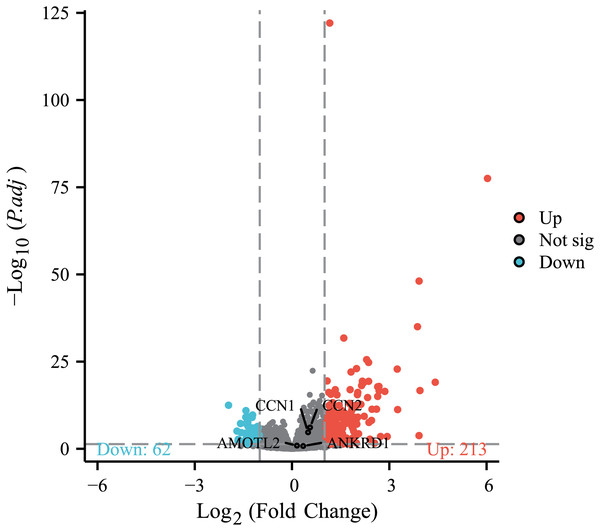

Supplementary bioinformatics analysis

To further investigate the association between MAFF and the core effector of the Hippo pathway, YAP1, at the transcriptome level, we analyzed the relationship between MAFF expression and the mRNA levels of YAP1 and its canonical target genes CTGF (CCN2), CYR61 (CCN1), AMOTL2 and ANKRD1 in the TCGA-LUAD cohort. The results showed no statistically significant differences in the mRNA expression levels of YAP1 itself or these target genes between the MAFF-high and MAFF-low expression groups (Fig. 10). This finding suggests that MAFF’s regulation of the YAP pathway may not occur at the transcriptional level.

Figure 10: Differential expression patterns of CTGF (CCN2), CYR61 (CCN1), AMOTL2 and ANKRD1 between high and low MAFF expression groups.

Additionally, we specifically examined MAFF expression in endothelial cells. Subclustering of endothelial cells revealed distinct populations (Fig. 11A). When categorized based on MAFF expression levels (Fig. 11B), we observed a decreasing trend in the proportion of the MAFF-low endothelial subpopulation within tumor tissues compared to normal tissues (Fig. 11C). This intriguing finding in the tumor vasculature compartment presents a contrast to the tumor-suppressive role of MAFF we identified in epithelial cells.

Figure 11: (A) Endothelial cell clustering results.

(B) Cells from clusters 0 and 2 were defined as the MAFF-high expression group, while cells from cluster 1 were defined as the low-expression group. (C) The MAFF-low cell subpopulation exhibited a decreasing trend in tumor tissues.Discussion

In this study, we systematically investigated the expression pattern and functional role of MAFF in NSCLC, elucidating its potential mechanisms in tumorigenesis and progression. Our results demonstrated that MAFF is significantly downregulated in NSCLC tissues, and its expression level strongly correlates with tumor angiogenesis. These findings provide novel insights into the potential of MAFF as a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target in NSCLC.

Bioinformatic analysis indicated that MAFF expression is significantly reduced in lung adenocarcinoma tissues compared to normal lung tissues. This observation was corroborated by IHC staining of clinical samples and WB assays in NSCLC cell lines. Functional studies further suggest that MAFF may exert tumor-suppressive roles through multiple mechanisms. In particular, MAFF likely modulates the Hippo signaling pathway, which plays a critical role in restraining tumor cell proliferation and invasion. Although our GSEA implicated MAFF in the Hippo pathway, supplementary data from the TCGA cohort revealed no correlation between MAFF expression and the mRNA levels of YAP1 or its canonical target genes (Fig. 10). This is highly consistent with the established understanding that the oncogenic activity of YAP1 is primarily regulated post-translationally, particularly through its nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, rather than at the level of its own transcription. Therefore, our functional experimental results—where MAFF overexpression significantly reduced YAP1 protein levels and suppressed its nuclear translocation, leading to the downregulation of downstream effector proteins like CTGF and VEGFA—precisely captured this critical regulatory layer and robustly explain the observed anti-angiogenic phenotype.

Moreover, single-cell RNA sequencing analysis revealed a substantial reduction of MAFF expression within the tumor microenvironment. This was evidenced not only by a decrease in MAFF-high epithelial subpopulations in tumors (Fig. 3E) but also by a trend of reduced MAFF-low endothelial cells (Fig. 11C). This downregulation was inversely correlated with the degree of tumor malignancy and MVD, implying that MAFF may suppress tumor growth and progression by inhibiting angiogenesis. The observed reduction in MAFF-low endothelial cells might seem counterintuitive at first glance. However, we interpret this as a potential secondary effect driven by the potent paracrine signaling from MAFF-deficient tumor epithelial cells. The abundant pro-angiogenic factors secreted by MAFF-low epithelial cells likely create a strongly mitogenic microenvironment, stimulating the expansion of the endothelial compartment and altering its transcriptional landscape, which may account for the shift in endothelial subpopulation proportions. This interpretation underscores that the cell-autonomous loss of MAFF in the tumor epithelium is the primary event, leading to non-cell-autonomous remodeling of the vascular niche. Our comprehensive study underscores the importance of MAFF in NSCLC pathogenesis and highlights its potential as a therapeutic target for future intervention strategies.

Further investigations confirmed that MAFF significantly inhibits tumor cell proliferation, clonogenicity, migration, and invasion. Notably, MAFF overexpression led to a marked reduction in tumor volume in nude mouse xenograft models, reinforcing its tumor-suppressive function. Tumor progression depends not only on the intrinsic proliferative capacity of cancer cells but also on support from the tumor microenvironment, where angiogenesis is a pivotal process. Immunohistochemical analyses showed that MAFF overexpression significantly decreased MVD in tumor tissues, concomitant with the downregulation of VEGFA—a key regulator of angiogenesis. Collectively, these findings suggest that MAFF restrains tumor growth and progression, at least partially, through anti-angiogenic mechanisms. This conclusion is consistent with the tumor-suppressive effects observed in both in vitro and in vivo settings, emphasizing the functional importance of MAFF in controlling NSCLC development.

The role of MAFF as a multifunctional transcription factor in cancer is complex and highly context-dependent. In bladder cancer, elevated MAFF levels are associated with improved patient survival (Guo et al., 2020), while in advanced cutaneous melanoma, MAFF acts as a protective factor (Shi et al., 2024). In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), MAFF overexpression inhibits cell proliferation and colony formation and promotes apoptosis, supporting its function as a tumor suppressor in this context (Wu et al., 2020). Conversely, in LUAD, MAFF exhibits oncogenic properties through a dual mechanism: it suppresses SLC7A11 and CDK6 expression and upregulates CDKN2C, leading to ferroptosis and G1-phase cell cycle arrest. Additionally, MAFF-driven metabolic reprogramming enhances sensitivity to therapy (Liang et al., 2024). In other malignancies, however, MAFF demonstrates pro-tumorigenic effects. For example, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), gemcitabine treatment promotes PRMT1 nuclear translocation, which methylates and disrupts the recruitment of the MAFF/BACH1 complex to pro-apoptotic gene promoters, thereby inducing chemoresistance (Nguyen et al., 2024). Similarly, in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment of breast cancer, HIF-1α activates MAFF, facilitating its heterodimerization with BACH1. This complex activates the IL-11/STAT3 pathway, driving tumor invasion and metastasis, which correlates directly with poor patient prognosis (Moon et al., 2021). The context-dependent duality of MAFF— functioning as either an oncogene or a tumor suppressor—likely stems from its molecular plasticity, influenced by three intersecting determinants: tissue-specific dimerization preferences, epigenetic landscapes, and microenvironmental signals.

Furthermore, this study revealed that MAFF regulates tumor angiogenesis by suppressing YAP1 nuclear translocation. MAFF overexpression significantly reduced YAP1 nuclear localization, likely through activation of the Hippo signaling pathway. Specifically, MAFF downregulated YAP1 expression by inhibiting its promoter activity, thereby limiting the pool of YAP1 available for nuclear import. Through this mechanism, MAFF effectively disrupts YAP1-mediated pro-angiogenic signaling.

As a core effector of the Hippo pathway, YAP1 subcellular localization is tightly regulated: activation of LATS1/2 kinase promotes YAP1 phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention, whereas LATS1/2 inhibition leads to YAP1 dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation, where it partners with TEAD transcription factors to activate downstream genes (Zhao et al., 2007). YAP1 drives angiogenesis via multiple mechanisms, including transcriptional induction of pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF through the YAP1/TEAD complex, and direct upregulation of targets like CTGF to facilitate endothelial cell migration and vascular network assembly (Zhao et al., 2008). Additionally, sustained YAP1 activation promotes vasculogenic mimicry via induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stemness (Yu et al., 2018; Lv et al., 2022).

The inhibition of YAP1 by MAFF may therefore target both classical angiogenic and vasculogenic mimicry pathways, providing a mechanistic basis for the potent anti-angiogenic effects observed in this study. Targeting the YAP1–TEAD interaction represents a promising therapeutic strategy, as evidenced by studies showing that a VGLL4-mimetic peptide competitively inhibits YAP1 binding to TEAD, suggesting potential for novel combination therapies targeting the MAFF–YAP1 axis (Jiao et al., 2014).

This study further demonstrates that MAFF exerts a critical regulatory role in tumor angiogenesis by suppressing the expression of YAP1 and its downstream target genes, VEGFA and CTGF. This mechanism was rigorously validated using multidimensional experimental approaches, including WB, IHC, and nude mouse xenograft models. Previous experimental evidence indicates that the YAP1-TEAD transcription complex directly binds to the promoter regions of VEGFA and CTGF, activating their transcription and thereby promoting endothelial cell proliferation and vascular network formation (Hiemer, Szymaniak & Varelas, 2014). As a central regulator of tumor angiogenesis, VEGFA exhibits a significant positive correlation with microvessel density (MVD) and tumor growth rate (Ferrara, 2002). The transcriptional regulation of VEGFA by YAP1 is dependent on its interaction with TEAD. Furthermore, VEGFA enhances endothelial cell migration and vascular permeability by activating VEGFR-2 receptors, which in turn induces phosphorylation of key downstream signaling effectors such as those in the ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways (Weis & Cheresh, 2011). Together, these findings underscore the pivotal role of the YAP1/TEAD/VEGFA axis in tumor angiogenesis and highlight its potential as a target for anti-angiogenic therapy.

CTGF, another well-established downstream target of YAP1, contributes to angiogenesis by modulating extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and fibroblast activation. Specifically, CTGF binds to integrin αvβ3 on fibroblasts, which activates the FAK/Src signaling pathway. This signaling cascade enhances the deposition of fibronectin and promotes the oriented alignment of collagen fibers, thereby providing mechanical support essential for nascent blood vessel stability (Chaqour & Goppelt-Struebe, 2006). Notably, the YAP1/CTGF axis also facilitates the formation of vasculature-like structures under hypoxic conditions. This dual role—affecting both classical angiogenesis and vasculogenic mimicry—highlights the functional significance of the YAP1/CTGF axis and suggests its potential as a therapeutic target in anticancer strategies.

Finally, our study has certain limitations that point to important directions for future research. While we demonstrate that MAFF overexpression suppresses YAP1 nuclear translocation and downstream angiogenesis, the most direct validation—using a YAP1-TEAD inhibitor (e.g., Verteporfin) in our in vivo model to confirm that the anti-tumor and anti-angiogenic effects of MAFF are primarily YAP1-dependent—was not conducted due to the time constraints of animal experimental cycles. Nevertheless, extensive literature robustly supports this mechanistic link. It is well-established that Verteporfin, by disrupting the YAP1-TEAD interaction, inhibits the transcription of pro-angiogenic genes like VEGFA and CTGF, thereby suppressing endothelial cell tube formation and tumor angiogenesis in various cancers (Liu-Chittenden et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2017; Dong et al., 2018). This established paradigm strongly aligns with our phenotypic observations following MAFF overexpression, providing compelling indirect evidence for our proposed model.

Furthermore, the precise upstream mechanism by which MAFF inhibits YAP1 nuclear localization remains to be fully elucidated. Our current data, showing cytoplasmic retention of YAP1 upon MAFF overexpression, suggest an impact on the Hippo pathway activity. However, it is still unclear whether MAFF directly influences the trafficking of YAP1 or acts via modulating key inhibitory components of the Hippo cascade, such as LATS1/2 or NF2. Future studies should include Western blot analysis of phosphorylated YAP1 (Ser127) and core Hippo kinases to determine if MAFF activates this inhibitory pathway.

Based on these considerations, our subsequent research will prioritize two key objectives: (1) employing YAP1-TEAD inhibitors in combination with MAFF modulation in in vivo tumor models to conclusively establish causal dependency, and (2) systematically investigating the effect of MAFF on the phosphorylation status of YAP1 and the expression/activity of upstream Hippo pathway regulators. Additionally, a critical future experiment will involve treating MAFF-modulated NSCLC cells with a YAP1-TEAD inhibitor and then applying the conditioned medium to HUVECs. This setup will directly test whether the anti-angiogenic effect of MAFF is executed primarily through suppressing the YAP-driven secretome in tumor cells. Despite these limitations, our findings conclusively establish the MAFF-YAP1 axis as a significant regulator of angiogenesis in NSCLC, offering a novel conceptual framework for future therapeutic exploration.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that MAFF is significantly downregulated in NSCLC and closely associated with tumor angiogenesis. Our findings reveal that MAFF attenuates the nuclear translocation of YAP1 and markedly downregulates the expression of its downstream effectors VEGFA and CTGF, thereby suppressing the angiogenic potential of NSCLC cells. These results imply that MAFF may play a role in the pathogenesis and progression of NSCLC, offering novel clinicopathological and molecular insights. However, the prognostic significance of MAFF in lung cancer patients requires further validation. Future studies should include large-scale cohort analyses to better define its utility as a biomarker and therapeutic target. Further investigation is also warranted to elucidate the direct interplay between MAFF and YAP1 or other components of the Hippo pathway, as well as to explore the potential of MAFF in combination treatment strategies involving anti-angiogenic agents and immune checkpoint inhibitors—an important direction for subsequent research.

Supplemental Information

Tumors in Animal Models.

For studies involving tumors in animal models, tumor size was reported, and evidence was provided in the form of photos and tables.