Note: This was part of a talk I gave last week for Open Access Week at the University of Edinburgh. A slideshare of the deck is available.

I grew up in ‘Silicon Valley’ during the late 70s and 80s, before moving a bit North near Berkeley. What a fantastic stroke of luck that was. My dad was an electrical engineer and my mother a fiber optic planner, so not the stereotypical computer engineer of the valley. They weren’t really techies either, but they did get us Pong, Atari 400, and Atari 2600. The Atari 400, which one was able to program on (even if terribly self taught), is what set me on a life long course of being involved with tech and science. [As well as sitting with my dad as he watched Star Trek, PBS, and David Attenborough] For that I am grateful.

Living in Silicon Valley you couldn’t help, even as a kid, but absorb the emerging personal computer and software scene. I was too young to remember the launch, but the Apple II in 1977 set off the personal computer revolution. Later, the 1984 Macintosh extended that. Finally there was a computer for the masses. It was a beautiful package at the time that made it convenient to get stuff done. It created new jobs and an entirely new industry – and impacted all other industries.

A similar thing happened 350 years ago in 1666. It was called “Philosophical Transactions” and it was the first (or close to it) journal of science. Like the Apple II, it conveniently packaged the greatest information of the time to help people get stuff done. It created new jobs, opportunities, and industries. It stands as testament that more than 350 years on we still have the concept of the journal with research papers. It’s worked fantastically, until recently. It’s now apparent that there are at least two major problems with the research article as a packaged form of research. I’ll explain the first problem:

It’s now apparent that there are at least two major problems with the research article as a packaged form of research. I’ll explain the first problem:

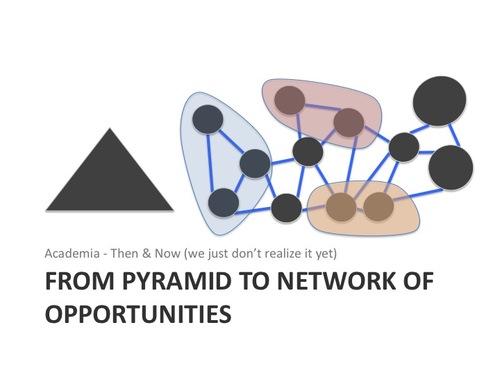

Due to its convenience, the research article became the standard for the CV, it was the currency that allowed you to easily show what you’ve accomplished. This makes sense. So, if you want a new academic position just publish and then show your work to prospective institutions. This worked really well when the number of scientists was much smaller than today. And pre/post WWII there was an explosion of funding available and new positions being created. At some point though, the number of new scientists started to outweigh the available positions and funding. When that happens, like an overcrowded city, the only way to expand is upward – and you end up with a pyramid.  This is why on the order of only 1 in 6 post-docs will be able to obtain a tenured academic position in their careers. This is why pay for those post-docs is low, and why most grad students and post-docs leave for industry, and usually non-research industries. This is directly related to using the research article as our only/main currency in research. Why that is directly related can be explained by investigation of the second major problem of the research paper.

This is why on the order of only 1 in 6 post-docs will be able to obtain a tenured academic position in their careers. This is why pay for those post-docs is low, and why most grad students and post-docs leave for industry, and usually non-research industries. This is directly related to using the research article as our only/main currency in research. Why that is directly related can be explained by investigation of the second major problem of the research paper.

For centuries we have gathered data in the form of experimental observations, presentations, building reference lists, informal conversations with colleagues, etc. We then wrote that up as the research article to neatly explain all of that data. However, because there was no technology or infrastructure it was either impossible to store that data or prohibitively expensive. So we filtered those data contributions down until we could arrive at the article. This filtering happened not only because we couldn’t store that data, but because the research article became the main incentive to advancing our careers. We tend to discard non-incentives. You can’t innovate with what you don’t have – and that’s what the research article did for us – it threw out an untold amount of information that could have been used to spark innovation and create new jobs. These filtered or lost data contributions include hard contributions like individual data points, negative data, machine and environment states, supporting software and hardware, materials and reagents. Then there are the “soft contributions” that were filtered such as: our ideas, lab notes, conference talks, uncited references that are collected, closed peer-reviews, author rebuttals, etc.

This filtering happened not only because we couldn’t store that data, but because the research article became the main incentive to advancing our careers. We tend to discard non-incentives. You can’t innovate with what you don’t have – and that’s what the research article did for us – it threw out an untold amount of information that could have been used to spark innovation and create new jobs. These filtered or lost data contributions include hard contributions like individual data points, negative data, machine and environment states, supporting software and hardware, materials and reagents. Then there are the “soft contributions” that were filtered such as: our ideas, lab notes, conference talks, uncited references that are collected, closed peer-reviews, author rebuttals, etc.

We live in a world of hidden information

Or at least we used to. We didn’t stop with the Apple II of course. We started doing things like putting sensors into every thing. We developed new open source software to observe and explain the world, and to expand into even more tools and software. We built APIs to leverage massively powerful technologies. And today we have this highly connected world that is amazing. We can speak into our phones “weather” and it will talk to a server far away, recognize that we mean “weather” instead of “whether”, it will know our location, and return the week’s weather report all in seconds. We can do the same thing for real-time traffic reports on our phones or computers. This and much more because we exposed and captured the world’s “hidden” data that we previously discarded for all of human history. This previously hidden data now drives new jobs and industries that is seemingly perpetual.

Why though can we get real-time traffic updates on our phones, but can’t ask something simple about the current state of running lab equipment? For example, why can’t we speak “PCR” into our phones and get back the current conditions, did the primers anneal properly, and if not tell our PCR to order new ones. Or are there any other recently ran PCR experiments in the world looking at similar sequences? Or have any papers just been published that mention sequences currently in my PCR? etc…. Why can’t a list of similar researchers show up as a side bonus when I ask my phone ‘PCR?’ All of these and much more SHOULD be possible with today’s technology, but they aren’t. And just like the rest of the world two decades ago, it is because we aren’t storing and connecting academic contributions like we could be doing.

It’s clear that if we’re going to solve the greatest challenges facing us, and stop that academic pyramid from getting steeper, then we need to stop throwing away all of our contributions. It turns out that we’re starting to recognize this fact, and there has been a small explosion of what we could think of as “Contributions as a Service.” A few of these services are listed in the graphic below. Some are for-profit, some non-profit, some government, some university-based, some closed source, some open, etc.

It turns out that we’re starting to recognize this fact, and there has been a small explosion of what we could think of as “Contributions as a Service.” A few of these services are listed in the graphic below. Some are for-profit, some non-profit, some government, some university-based, some closed source, some open, etc.

Most contributions, however, still come from a countless number of machines that we’re starting to store and analyze data from in a reusable way.

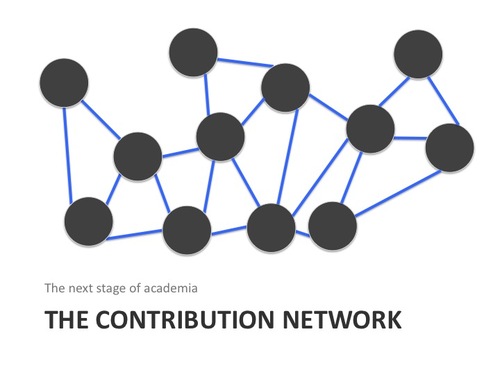

Together, these machine and human researcher contributions are starting to be connected. We don’t realize yet, but we’re already on the way to creating “The Contribution Net.” This is the next stage for academia, one that will eventually replace the academic pyramid. It is this Contribution Net that will create new jobs, new innovations, and new cures in this century and beyond, just as the “Internet of things” is doing in the tech industry for our homes, offices, non-tech jobs, and of course our phones.

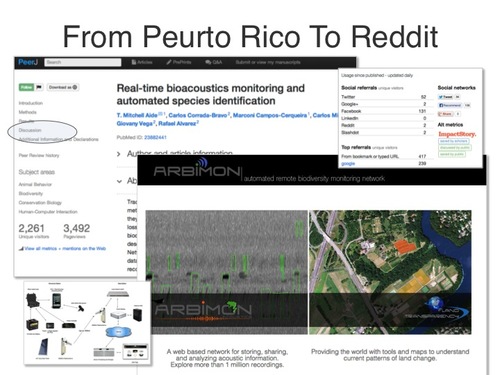

One way we’re seeing the Contribution Net manifest itself is through “citizen science.” Recently at PeerJ we published a paper about real-time bioacoustics monitoring. Long before the paper was started, the researchers were gathering data in a Puerto Rico jungle with hacked together iPods, solar panels, satellites, and servers. The recordings of the jungle were sent back to the lab where the different species were identified via software. Rather than disposing of those recordings after publishing the research, the authors have made them available to anyone to download and reuse, and possibly help identify more species.

One way we’re seeing the Contribution Net manifest itself is through “citizen science.” Recently at PeerJ we published a paper about real-time bioacoustics monitoring. Long before the paper was started, the researchers were gathering data in a Puerto Rico jungle with hacked together iPods, solar panels, satellites, and servers. The recordings of the jungle were sent back to the lab where the different species were identified via software. Rather than disposing of those recordings after publishing the research, the authors have made them available to anyone to download and reuse, and possibly help identify more species.

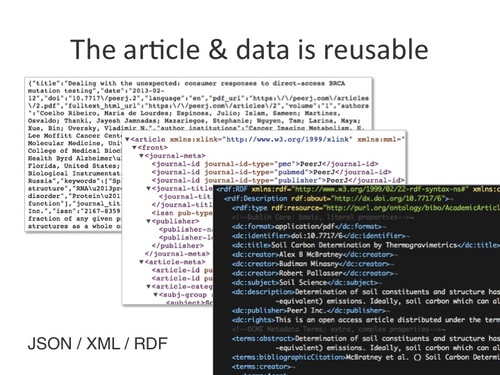

The great part about this is that machines too can participate, starting with the publication, which is marked up in a language that machines can understand and reuse.

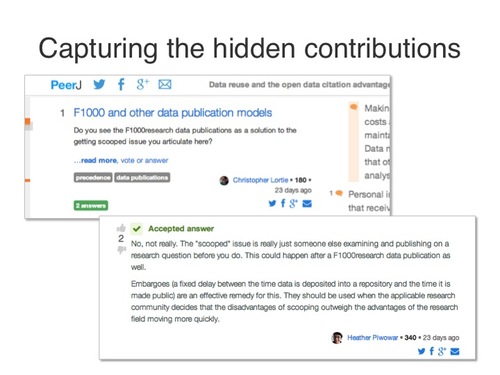

Another example of how important the Contribution Net is comes from the recent ‘Dinosaur Joe’ paper published as Open Access on PeerJ. This was a fantastic find, and the authors worked hard to make this the most digitally accessible dinosaur ever. On PeerJ it saw more than 4,000 unique visitors on the first day. The amazing part though is that the researchers created an easy to understand website for the public to understand and analyze the findings. Because they did that, it had more than 75,000 unique visitors on the first day, far surpassing the research article itself. Had the researchers not made that website then there would have been a lot of people who would have never taken the time to learn about this discovery. This is truly a case where the impact from the data and work peripheral to the paper was greater than the paper itself. This is happening all over, yet for the most part we haven’t been connecting that information. We’ve been throwing it out to create the paper. We’re also starting to capture and reuse the “soft contributions” such as article discussions. The National Library of Medicine is in beta testing with “PubMed Commons,” which is a way for academics to comment on articles on PubMed. At PeerJ we just released “PeerJ Questions,” which gives anyone the tools to ask inline questions on articles and for anyone else to answer. The information is structured and exposed in a reusable annotation ontology in the hopes that others can also make use of it and connect the dots with other annotations such as PubMed and eventually machine contributions that are related.

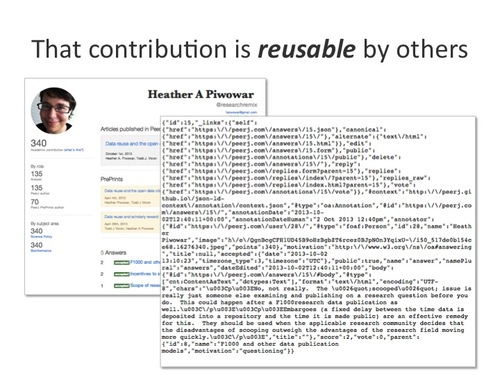

We’re also starting to capture and reuse the “soft contributions” such as article discussions. The National Library of Medicine is in beta testing with “PubMed Commons,” which is a way for academics to comment on articles on PubMed. At PeerJ we just released “PeerJ Questions,” which gives anyone the tools to ask inline questions on articles and for anyone else to answer. The information is structured and exposed in a reusable annotation ontology in the hopes that others can also make use of it and connect the dots with other annotations such as PubMed and eventually machine contributions that are related.

The bonus is that everyone making these contributions is included in that machine-readable data, which is key to ensuring the research paper isn’t the only credit and incentive in academia. These might just be small scale experiments at the moment, but this is where the Contribution Net is headed.

The Power of the Contribution Net When you look at the Contribution Net it becomes obvious that the nodes and edges can be grouped, expanded, etc on their own. This is why it is so much more powerful than the academic pyramid reliant on the research paper. A similar connected graph of the World Wide Web is what made Google’s PageRank algorithm so powerful. Of course, to be able to make these connections requires an open Contribution Net. This raises the question of who will own this network? And will it become open or closed?

When you look at the Contribution Net it becomes obvious that the nodes and edges can be grouped, expanded, etc on their own. This is why it is so much more powerful than the academic pyramid reliant on the research paper. A similar connected graph of the World Wide Web is what made Google’s PageRank algorithm so powerful. Of course, to be able to make these connections requires an open Contribution Net. This raises the question of who will own this network? And will it become open or closed? Already there are groups trying to control large swathes of the contributions being made; in many cases contributions that are already open. For example, CHORUS is an initiative from the Association of American Publishers (mostly pay wall publishers). CHORUS is trying to replace the open PubMed infrastructure and APIs with a single publisher-controlled portal to find publicly funded (Open) research papers. If we want to have an open Contribution Net and solve our greatest research challenges then the way forward is not by starting with a solution controlled by entities whose business model depends on making information scarce. The temptation to close it off would be too great.

Already there are groups trying to control large swathes of the contributions being made; in many cases contributions that are already open. For example, CHORUS is an initiative from the Association of American Publishers (mostly pay wall publishers). CHORUS is trying to replace the open PubMed infrastructure and APIs with a single publisher-controlled portal to find publicly funded (Open) research papers. If we want to have an open Contribution Net and solve our greatest research challenges then the way forward is not by starting with a solution controlled by entities whose business model depends on making information scarce. The temptation to close it off would be too great.

Finally, we must work to establish open data standards, so that contributions (from researchers and machines) can be interoperable as much as possible. This is why at PeerJ we’re looking to work with PubMed and others to ensure the new comment annotations are interoperable with other services such Hypothes.is and PeerJ Questions, which use the open annotation ontology standard.

All of this isn’t to say that there isn’t a need for the research paper, quite the contrary as the ‘paper’ serves a valuable purpose on its own as well. However, we need to start thinking of research papers as a byproduct, not the end product of academic efforts. We need to swap the paper pyramid with a more connected contribution network in order to create more jobs, better pay, and new solutions for a century with greater challenges ahead.

Jason Hoyt is a co-founder of PeerJ, along with Pete Binfield.