A revised terminology for male genitalia in Hymenoptera (Insecta), with a special emphasis on Ichneumonoidea

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Tony Robillard

- Subject Areas

- Entomology, Evolutionary Studies, Taxonomy, Zoology

- Keywords

- Confocal laser scanning microscopy, Male genitalia, Hymenoptera anatomy ontology, Ichneumonoidea, Braconidae, Ichneumonidae, Homology, Ontology, Unified terminology, Comparative anatomy

- Copyright

- © 2023 Dal Pos et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2023. A revised terminology for male genitalia in Hymenoptera (Insecta), with a special emphasis on Ichneumonoidea. PeerJ 11:e15874 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15874

Abstract

Applying consistent terminology for morphological traits across different taxa is a highly pertinent task in the study of morphology and evolution. Different terminologies for the same traits can generate bias in phylogeny and prevent correct homology assessments. This situation is exacerbated in the male genitalia of Hymenoptera, and specifically in Ichneumonoidea, in which the terminology is not standardized and has not been fully aligned with the rest of Hymenoptera. In the current contribution, we review the terms used to describe the skeletal features of the male genitalia in Hymenoptera, and provide a list of authors associated with previously used terminology. We propose a unified terminology for the male genitalia that can be utilized across the order and a list of recommended terms. Further, we review and discuss the genital musculature for the superfamily Ichneumonoidea based on previous literature and novel observations and align the terms used for muscles across the literature.

Introduction

The importance of a unified morphological terminology

The study of morphology entails the interpretation of anatomical structures shaped by evolutionary processes and their translation into rigorous and consistent data (Boudinot, 2019). This practice requires the application of terms and concepts for effectively identifying and describing the structures. However, terminologies employed in different groups of organisms can overlap and cause confusion. Homonyms, identical terms used for non-homologous structures, are widespread and employed to describe structures in unrelated taxa (e.g., Costa et al., 2013; Donkelaar et al., 2017). At the same time, homologous anatomical traits in related groups of organisms often have inconsistent terminologies (e.g., Schulmeister, 2001).

Inconsistent terminologies are widespread within and among insect orders (Yoder et al., 2010; Costa et al., 2013; Wirkner et al., 2017). Girón et al. (2023) identified five main reasons for the emergence of inconsistent terminologies within insects, namely: (1) borrowing terms from the vertebrate anatomy (e.g., wings, head); (2) creating terms de novo (e.g., sclerite, sternite); (3) applying terms to different insect lineages to refer to similar structures located in similar areas of the body (e.g., cercus in Diplura and cercus in Hymenoptera); (4) changes in phylogenetic classification that caused a reassessment of the morphological terminology; and (5) deviation in the original application of a term due a subsequent misinterpretation (e.g., the concepts of volsella). As pointed out by Yoder et al. (2010), the consequences of having disparate terminologies can negatively impact the comparison of gene expression patterns, comparative morphological and phylogenetic studies, analyses of phenotype variability, integration of descriptive taxonomy and phenomics, and machine learning algorithms.

Recently, efforts to address terminological inconsistencies have been undertaken with the intent to unify the terminology and standardize morphological data, and establish a comparability and communicability framework (e.g., Vogt, Bartolomaeus & Giribet, 2010). The idea is to use ontology, the logical and linguistic machinery for interpreting physical observations, to relate conceptual objects defined by their general identities and their specific properties, and to use controlled vocabularies for communication among scientists via stabilization of terminologies (Deans, Yoder & Balhoff, 2012; Boudinot, 2019; Girón et al., 2023). Examples of successful attempts are the Drosophila Anatomy Ontology (DAO) (Costa et al., 2013), the Ontology of Arthropod Circulatory Systems (OArCS) (Wirkner et al., 2017), the Hymenoptera Anatomy Ontology (HAO) (Yoder et al., 2010), and more recently the Insect Anatomy Ontology (Girón et al., 2023). Of these, the HAO provides an essential tool for hymenopterists but still lacks terms and concepts employed in different taxonomic groups (Boudinot, 2018; Lanes et al., 2020; de Brito, Lanes & Azevedo, 2021). For instance, within the hyperdiverse superfamily Ichneumonoidea ontological alignments for the different morphological structures are still severely lacking.

Among hexapods, the study of male genitalia has long captivated entomologists due to their essential function, diverse morphology, and mechanical adaptations. Even though in some insect orders, male genitalia play a fundamental role in phylogenetic and taxonomic studies (e.g., Song & Bucheli, 2010; Van Dam, 2014; Bollino, Uliana & Sabatinelli, 2018; Lackner & Tarasov, 2019), in Hymenoptera they have been relatively little explored (e.g., Schulmeister, 2001; Schulmeister, 2003; Boudinot, 2013), despite being recognized as a critical source of discrete and size-independent characters for both phylogenetic and taxonomic studies (e.g., Tuxen, 1970; Mikó et al., 2013; Boudinot, 2015). This is surprising given the high diversity and the great variety of forms and ecological roles of the order (more than 150,000 described species) (Klopfstein et al., 2013; Branstetter et al., 2018). One of the possible causes for this is that these characters tend to suffer from rampant terminological inconsistency (e.g., Tuxen, 1970), making study difficult.

Hymenopteran male genitalia: a terminological nightmare

The external male genitalia can offer many potential characters for taxonomic and phylogenetic studies due to their complexity, variability, and accessibility (at least compared to their internal counterparts). However, there are terminological inconsistencies across studies, likely resulting from two different interpretations of homologies based on two competing theories (Michener, 1956). The first, the periphallic origin theory, postulates that the male genitalia derived from true appendicular structures and are homologous across most insect orders (e.g., Crampton, 1919; Peck, 1937a; Peck, 1937b; Michener, 1944). This theory was recently corroborated by Boudinot (2018) (discussed further below). The second, the phallic origin theory, postulates that at least in Hymenoptera, the male genitalia have arisen de novo (e.g., Snodgrass, 1935; Snodgrass, 1941; Snodgrass, 1957). Early studies (e.g., Boulangé, 1924; Beck, 1933; Snodgrass, 1941; Michener, 1956; Smith, 1969; Smith, 1970a; Smith, 1970b; Togashi, 1970; Smith, 1972; Birket-Smith, 1981; Kopelke, 1981) attempted to provide a list of synonymous terms, but suffered from mistakes and incongruities, leading to an increase, rather than a reduction, of the confusion.

It was only with Schulmeister (2001) that the first modern and comprehensive work was produced, combining a complete list of synonyms with an attempt to understand the organization of the male copulatory organs in the basal lineages of Hymenoptera. Schulmeister (2003) then extended the analysis to the other Hymenoptera, providing the first morphological matrix for the order, making extensive use of characters from the male genitalia. Schulmeister’s (2001, 2003) analyses facilitated and bolstered further studies of genitalia within Hymenoptera, allowing subsequent refinement of terms (e.g., Boudinot, 2013; Mikó et al., 2013). However, more recently, Boudinot (2018) rejected the phallic origin theory and provided a new genital terminology for basal Hymenoptera, generating more confusion.

To ameliorate this terminological quagmire, and to facilitate future taxonomic and evolutionary studies, a modern study of the hymenopteran male genitalia is hereby presented. The current contribution provides: (1) a thorough review of the literature; (2) a list of the preferred terminology for the different skeleto-muscular elements of Hymenoptera accompanied by a list of synonyms; (3) the first unified terminology for the skeleto-muscular element of Ichneumonoidea; (4) an alignment of the musculature across the order Hymenoptera; and (5) confirmation of the presence or absence of muscles within Ichneumonoidea.

Materials and Methods

Sample preparations and imaging

Specimens used for dissection and imaging via confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) were collected in Manitoba (Canada), Florida (USA) and Arizona (USA) (Table 1), preserved in 70–90% ethanol and deposited at the University of Central Florida Collection (UCFC). Specimens collection at the Hal Scott Regional Preserve and Park was approved by St. Johns River Water Management District. Male genitalia were dissected by means of minuten pins under a dissecting stereomicroscope OPTIKA SZM-2 which was also used for observations. Specimens used for CLSM imaging were bleached in 30% H2O2 for two hours, then placed in a droplet of glycerol and imaged with a ZEIS 710 CLSM at the microscope facility of the Burnett School of Biomedical Sciences (University of Central Florida) using 405 and 488nm lasers (following Mikó & Deans (2013)). Autofluorescence was collected using three channels with assigned contrasting pseudocolors (420–520 nm, blue; 490–520 nm, green; and 570–670 nm, red). Volume-rendered images and media files were generated using ImageJ (Schindelin et al., 2015). Male genitalia not used in CLSM imaging were left to dry and then glued to the tip of a minuten pin and imaged using a Canon Eos 7D camera with a Canon MP-E 65 mm f/2.8 1-5 ×Macro and an M Plan Apo 10×Mitutoyo objective mounted onto the EF Telephoto 70–200 mm Canon zoom lens, and rendered using Zerene Stacker software v. 1.04. Images were enhanced using Photoshop 23.2.2.

| Subfamily | Taxon | Country | State/ Province | Locality | Collector(s) | Repository | Voucher number | Preservation method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cremastinae | Temelucha sp. | USA | Florida | Hal Scott Regional Preserve, Pine Flatwoods | D. Dal Pos & A. Pandolfi | UCFC | UCFMG_0000006 | Glycerol |

| Ichneumoninae | Coelichneumon sassacus (Viereck, 1917) | Canada | Manitoba | Whiteshell Prov. Pk., Pine Point Rapids Trail | Sharanowski lab | UCFC | UCFMG_0000001 | Point |

| Ichneumoninae | Melanichneumon lissorufus Heinrich, 1962 | Canada | Manitoba | Spruce Woods Prov. Pk. | Sharanowski lab | UCFC | UCFMG_0000002 | Point |

| Labeninae | Labena grallator (Say, 1835) | USA | Florida | Highland Co., Archbold Biological Station | Y. M. Zhang | UCFC | UCFMG_0000003 | Point |

| Labeninae | Labena grallator (Say, 1835) | USA | Florida | Hal Scott Regional Preserve, Cypress swamp | D. Dal Pos & A. Pandolfi | UCFC | UCFMG_0000016 | Glycerol |

| Mesochorinae | Mesochorus sp. | Canada | Manitoba | University of Manitoba, Points | UW/ELZ | UCFC | UCFMG_0000011 | Glycerol |

| Mesochorinae | Mesochorus sp. | Canada | Manitoba | University of Manitoba, Points | UW/ELZ | UCFC | UCFMG_0000014 | Glycerol |

| Mesochorinae | Mesochorus sp. | Canada | Manitoba | University of Manitoba, Points | UW/ELZ | UCFC | UCFMG_0000015 | Glycerol |

| Pimplinae | Pimpla marginella Brullé, 1846 | USA | Florida | Hal Scott Regional Preserve, Pine Flatwoods | D. Dal Pos & A. Pandolfi | UCFC | UCFMG_0000004 | Glycerol |

| Poemeninae | Neoxorides pilosus Townes, 1960 | Canada | Manitoba | Agassiz Prov. Pk. | Sharanowski lab | UCFC | UCFMG_0000012 | Glycerol |

| Tryphoninae | Netelia sp. | Canada | Manitoba | University of Manitoba, Points | UW/ELZ | UCFC | UCFMG_0000004 | Point |

| Tryphoninae | Netelia sp. | USA | Florida | Martin Co., Seabranch Preserve SP, Baygall | D. Serrano | UCFC | UCFMG_0000007 | Glycerol |

| Tryphoninae | Netelia sp. | USA | Arizona | Coconino Co., Tonto National Forest, 1 m W of Payson, 1440 m | D. Dal Pos & A. Pandolfi | UCFC | UCFMG_0000008 | Glycerol |

| Tryphoninae | Netelia sp. | USA | Arizona | Coconino Co., Tonto National Forest, 1 m W of Payson, 1440 m | D. Dal Pos & A. Pandolfi | UCFC | UCFMG_0000009 | Glycerol |

| Tryphoninae | Netelia sp. | Canada | Manitoba | Whiteshell Prov. Pk | Sharanowski lab | UCFC | UCFMG_0000017 | Glycerol |

| Rhyssinae | Rhyssa persuasoria (Linnaeus, 1758) | Canada | Manitoba | Whiteshell Prov. Pk. | Sharanowski lab | UCFC | UCFMG_0000010 | Glycerol |

| Xoridinae | Xorides eastoni (Rohwer, 1913) | Canada | Manitoba | Spruce Woods Prov. Pk | Sharanowski lab | UCFC | UCFMG_0000013 | Glycerol |

| Abbreviation | Label | Definition | URI |

|---|---|---|---|

| S9 | Abdominal sclerite 9 | The abdominal sternum that is located on abdominal segment 9. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000047 |

| aed | Aedeagus | The anatomical cluster that is composed of sclerites that are adjacent to the distal end of the ejaculatory duct | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000091 |

| ag | Apex gonostipitis | The apodeme that is located medially on the proximoventral margin of the gonostipes and is the site of origin of the ventral gonotyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscles | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000134 |

| aps | Apiceps | The area that is the distal part of the gonossiculus and is connected to the parossiculus via membranous conjunctiva | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000141 |

| bsr | Basiura | The area that is the proximal part of the gonossiculus and corresponds to the site of insertion of medial penisvalvo-gonossiculal muscle | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000179 |

| bs | Basivolsella | The area that is located on the parossiculus ventromedially of the cuspis | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001085 |

| c | Cupula | The sclerite that is connected via conjunctiva and attached via muscles to abdominal tergum 9 and the gonostyle/volsella complex | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000238 |

| cus | Cuspis | The projection that is located apicolaterally on the parossiculus and is adjacent to the digitus | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000239 |

| ejd | Ejaculatory duct | The duct that connects the vas deferens with the endophallus and is ectodermal in origin. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000283 |

| end | Endophallus | The conjunctiva that connects the gonopore with the penisvalvae | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000291 |

| erg | Ergot | The apodeme that is lateral, located medially on the penisvalva and corresponds to the sites of insertion of the lateral and distoventral gonostyle/volsella complex -penisvalval muscle and the parossiculo-penisvalval muscle | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000308 |

| fd | Fibula ducti | The sclerite that is located in the proximal end of the unpaired part of the ductus ejaculatorius | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000328 |

| fg | Foramen genitale | The anatomical space that is surrounded by the proximal margin of the cupula | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000346 |

| gnm | Gonomacula | The conjunctiva that is located at the distal apex of the harpe | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000382 |

| gss | Gonossiculus | The sclerite that is located on the distoventral part of the gonostyle/volsella complex, and is articulated with the more proximal sclerites of the gononstyle/volsella complex | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000385 |

| gst | Gonostipes | The sclerite that is located dorsolaterally on the gonostyle/volsella complex, is connected to the distal margin of the cupula, to the proximal margin of the harpe, and to the lateral margin of the volsella | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000386 |

| gsa | Gonostipital arm | The apodeme that is located proximally on the ventral part of the gonostipes | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000387 |

| gs | Gonostyle | The anatomical cluster that is composed of sclerites located distally of the cupula dorsolaterally of the volsella, and that surround the aedeagus | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000389 |

| hrp | Harpe | The sclerite that is located distally on the gonostyle/volsella complex and does not connect to the cupula, and does not connect to the volsella by conjunctiva or muscles | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000395 |

| mss | Median sclerotized style | The sclerite that is located ventrally between the penisvalvae | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000531 |

| prp | Parapenis | The area that is the dorsomedian part of the gonostipes and is the site of origin of the distodorsal and proximodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscles | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000692 |

| pss | Parossiculus | The sclerite that is connected via conjunctiva distomedially to the gonostipes, and articulates with the gonossiculus | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000703 |

| ph | Phallotrema | The anatomical space that is the distal opening of the endophallus | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000714 |

| pv | Penisvalva | The sclerite that is in the middle of the external male genitalia, surrounds the distal part of the ductus ejaculatorius and the endophallus. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000707 |

| pgp | Primary gonopore | The anatomical space that is the transition from the ductus ejaculatorius to the endophallus and therefore the transition from the internal to the external male genitalia. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000821 |

| sp | Spatha | The sclerite that is unpaired and located just dorsally of the basal part of the aedeagus in some Aculeata. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000942 |

| sv | Seminal vesicle | The anatomical space that functions as storage of spermatozoa | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001081 |

| spc | Spiculum | The apophysis that is located medially on the anterior margin of the abdominal sternum 9 and corresponds to the site of origin of the mediolateral S9-cupulal muscles | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000946 |

| ts | Testis | The gonad that is consisting of testis follicles, is connected with the vas deferens and seminal vesicle | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001007 |

| vd | Vas deferens | The duct that connect the testis with the ejaculatory duct | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001052 |

| vvc | Valviceps | The area that is the distal part of the penisvalva dorsally of the ergot | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001047 |

| vvr | Valvura | The area that is located proximally of the ergot on the penisvalva. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001050 |

| vol | Volsella | The anatomical cluster that is composed of the sclerites on the ventral part of the male genitalia that are not connected to the cupula via muscles | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001084 |

| Abbreviation | Label | Definition | URI |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-gsdl | Dorsolateral cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex | The cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle that arises from the dorsolateral part of the cupula, just laterally of the site of origin of the dorsomedian cupulo-gonostipal muscle, and inserts on the dorsolateral part of the gonostipes | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000278 |

| c-gsdm | Dorsomedial cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle | The cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle that inserts medially on the dorsal region of the gonostyle/volsella complex | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000279 |

| c-gsvl | Ventrolateral cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle | The cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle that inserts ventrolaterally on the gonostyle/volsella complex between the site of insertion of the ventromedial and dorsolateral cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscles. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001074 |

| c-gsvm | Ventromedial cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle | The cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle that inserts medially on the ventral region of the gonostyle/volsella complex. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0001075 |

| gn-pssd | Distal gonostipo-parossiculal muscle | The gonostyle/parossiculal muscle that arises distally of the lateral part of the gonostipes and inserts on the distal part of the parossiculus distally of the site of origin of the proximal gonostipo-parossiculal muscle | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000247 |

| gn-pssp | Proximal gonostipo-parossiculal muscle | The gonostyle-parossiculal muscle that arises proximally from the lateral part of the gonostipes and inserts on the proximal part of the parossiculus | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000876 |

| gs-gs | Intragonostyle muscle | The muscle that connects the ventral and dorsal walls of the gonostyle basally | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0002581 |

| gs-pss | Gonostyle/volsella complex-parossiculal muscle | The muscle that arises ventromedially from the gonostyle, is proximomedially oriented, and inserts on the proximalmost sclerite of the volsella. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0002041 |

| gs-pvdd | Distodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscles | The dorsal gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle that arises distodorsally from the gonostyle volsella complex and inserts on the proximal region of the penisvalva | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000250 |

| gs-pvdv | Distoventral gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscle | The ventral gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle that arises from the proximoventral part of the gonostyle/volsella complex, inserts medially on the penisvalva and is oriented distodorsally | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000251 |

| gs-pvl | Lateral gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle | The gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle that arises anterolaterally of the site of origin of the distodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle and inserts laterally on the penisvalva | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000472 |

| gs-pvpd | Proximodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalva muscle | The dorsal gonostyle/volsella complex penisvalval muscle that arises proximodorsally from the gonostyle/volsella complex and inserts on the penisvalva distally of the site of insertion of the distodorsal gononstyle/volsella complex-penisvalva muscle. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000877 |

| gs-pvpv | Proximoventral gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscle | The ventral gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle that arises ventromedially from the gonostyle/volsella complex, inserts on the proximal end of the penisvalva and is oriented proximodorsally | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000879 |

| gss-ph | Gonossiculo-phallotremal muscle | The muscle that arises from the gonossiculus and inserts on the phallotrema. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0002577 |

| ha-gon | Harpo-gonomaculal muscle | The male genitalia muscle that arises form the harpe and inserts on the gonomacula | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000396 |

| gs-hra | Apical gonostyle/volsella complex - harpal muscles | The gonostyle/volsellal complex-harpal muscle that arises from the distolateral margin of the gonostyle/volsellal complex and inserts on the lateral wall of the harpe | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000246 |

| ga-hrd | Distal gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle | The gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle that inserts on the median wall of the harpe and arises distally of the site of origin of the proximal gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000336 |

| gs-hrp | Proximal gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle | The gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle that inserts on the median wall of the harpe and arises proximally of the site of origin of the distal gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000926 |

| imvl | Median gonostyle/volsella complex-volsella muscle | The gonostyle/volsella complex-volsellal muscle that arises medially of the submedian conjunctiva on the distoventral margin of gonostyle/volsella complex | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000473 |

| imvll | Lateral gonostyle/volsella complex-volsella muscle | The gonostyle/volsella complex-volsellal muscle that arises laterally of the submedian conjunctiva on the distoventral margin of gonostyle/volsella complex | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0002580 |

| imvm | Gonostyle/volsella complex-gonossiculus muscle | The gonossiculal muscle that arises ventromedially from the gonostyle/volsella complex and inserts laterally on the gonossiculus | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000517 |

| pss-ph | Parossiculo-phallotremal muscle | The male genitalia muscle that originates from the parossiculus and inserts on the endophallic membrane around the phallotrema | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000702 |

| pss-pv | Parossiculo-penisvalval muscle | The male genitalia muscle that arises from the proximal apex of the parossiculus and inserts medially on the penisvalva. The muscle inserts on the ergot if present. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000701 |

| pv-gssl | Lateral penisvalvo-gonossiculal muscle | The penisvalvo gonossiculal muscle that is lateral to the medial penisvalvo-gonossiculal muscle and attaches to the apiceps | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0002579 |

| pv-gssm | Medial penisvalvo-gonossiculal muscle | The penisvalvo-gonossiculal muscle that is medial to the lateral penisvalvo-gonossiculal muscle and attaches to the basiura. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0002578 |

| pv-mss | Penisvalvo-median sclerotized style muscle | The muscle that attaches to the median sclerotized style and to the valvura. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0002582 |

| pv-ph | Penisvalvo-phallotremal muscle | The male genitalia muscle that arises from the medial surface of the proximal part of the penisvalva and inserts on the endophallus just around the phallotrema. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000710 |

| pv-pv | Interpenisvalval muscle | The male genitalia muscle that connects the valvurae. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000433 |

| S9-cl | Lateral S9-cupulal muscle | The S9-cupulal muscle that arises sublaterally from S9 and inserts medioventrally on the cupula | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000464 |

| S9-cm | Medial S9-cupulal muscle | The male genitalia muscle that arises from the spiculum and inserts on the gonocondyle | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000516 |

| S9-cml | Mediolateral S9-cupulal muscle | The cupulal muscle that arises medially from abdominal sternum 9 and inserts ventrolaterally on the cupula | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000533 |

| vl-vl | Intervolsellal muscle | The male genitalia muscle that connects the proximal part of parossiculi. | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/HAO_0000441 |

| Abbreviation | Label | Boulangé (1924) | Peck (1937a); Peck (1937b) | Snodgrass (1941) | Alam (1952) | Schulmeister (2001); Schulmeister (2003) | Mikó et al. (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S9-cm | Medial S9-cupulal muscle | a | A | 1 | 2 | a | – |

| S9-cml | Mediolateral S9-cupulal muscle | b | B | 2 | 3 | b | Mediolateral S9-cupulal muscle |

| S9-cl | Lateral S9-cupulal muscle | c | C | 3 | 1 | c | Lateral S9-cupulal muscle |

| c-gsvm | Ventromedial cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle | d | D | 4 | 7 | d | Ventromedial cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle |

| c-gsvl | Ventrolateral cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle | e | E | 5 | 4, 5 | e | Ventrolateral cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle |

| c-gsdl | Dorsolateral cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex | f | F | 7 | – | f | Dorsolateral cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex |

| c-gsdm | Dorsomedial cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle | g | G | 6 | 6 | g | Dorsomedian cupulo-gonostyle/volsella complex muscle |

| gs-pvpv | Proximoventral gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscle | h | H | 8 | 14 | h | Proximoventral gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalva muscle |

| gs-pvdv | Distoventral gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscle | i | I | 9 | 15 | i | Distoventral gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscle |

| gs-pvdd | Distodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscles | j | J | 10 | 13 | j | Distodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscles |

| gs-pvpd | Proximodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalval muscle | k | K | 11 | 16 | k | Proximodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex - penisvalva muscle |

| gs-pvl | Lateral gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle | l | L | 12 | 18 | l | Lateral gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle |

| pv-gssl | Lateral penisvalvo-gonossiculal muscle | m | M | 22 | 12 | m | – |

| pv-gssm | Medial penisvalvo-gonossiculal muscle | – | n | – | |||

| pv-ph | Penisvalvo-phallotremal muscle | n | N | 24 | 17 | nb | – |

| gss-ph | Gonossiculo-phallotremal muscle | – | nd | – | |||

| pss-ph | Parossiculo-phallotremal muscle | – | nl | – | |||

| gs-pss | Gonostyle/volsella complex-parossiculal muscle | – | – | o | Gonostyle/volsella complex-parossiculal muscle | ||

| gn-pssp | Proximal gonostipo-parossiculal muscle | o | O | 18 | 8 | o’ | – |

| gn-pssd | Distal gonostipo-parossiculal muscle | 20 | – | o” | – | ||

| imvll | Lateral gonostyle/volsella complex-volsella muscle | p | P | 19 | 10 | p | Lateral gonostyle/volsella complex-volsella muscle |

| imvl | Median gonostyle/volsella complex-volsella muscle | q | Q | 21 | 9 | qr | Medial gonostyle/volsella complex-volsella muscle |

| r | R | ||||||

| imvm | Gonostyle/volsella complex-gonossiculus muscle | s | S | 23 | 11 | s | Gonostyle/volsella complex-gonossiculus muscle |

| pss-pv | Parossiculo-penisvalval muscle | si | – | – | – | si | Parossiculo-penisvalval muscle |

| gs-hrd | Distal gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle | t | T | 16 | – | t’ | Distal gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle |

| gs-hrp | Proximal gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle | 15 | – | t” | Proximal gonostyle/volsella complex-harpal muscle | ||

| ga-hra | Apical gonostyle/volsella complex - harpal muscles | u | U | – | – | u | Distal gonostipes/volsella complex-harpal muscle |

| ha-gon | Harpo-gonomaculal muscle | v | V | 17 | – | v | – |

| gs-gs | Intragonostyle muscle | – | – | – | w | – | |

| pv-pv | Interpenisvalval muscle | x | – | 13 | – | x | – |

| vl-vl | Intervolsellal muscle | – | – | – | y | – | |

| pv-mss | Penisvalvo-median sclerotized style muscle | z | – | 14 | – | z | – |

Morphological nomenclature

Differently from previous authors who used letters (e.g., Boulangé, 1924; Schulmeister, 2001; Schulmeister, 2003) or numbers (e.g., Snodgrass, 1941; Alam, 1952) to label the different muscle bundles, we follow Daly (1964), Friedrich & Beutel (2008), Vilhelmsen (1996); Vilhelmsen (2000a); Vilhelmsen (2000b), and Mikó et al. (2007); Mikó et al. (2013), referring to the muscles as follows: the first component of the name refers to the site of origin, while the second refers to the site of insertion of the muscle. For example, the proximoventral gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalva muscle is the muscle that is attached to the gonostyle/volsella complex and to the penisvalva. The proximoventral location differentiates it from the other gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalva muscles.

For deciding the preferred term among synonyms, we follow the criteria established by de Brito, Lanes & Azevedo (2021), with the integration of a new criterion (not in order of importance or priority): (1) the term that best represents the skeletal feature (shape and location of the body); (2) the term that is most widely used; (3) the term that was first introduced (oldest); (4) the term not employed also for other structures in other taxa (homonymy).

A list of the unified terminology employed here is provided in Tables 1–4 along with associated abbreviations and definitions included into an ontological framework.

Morphological concepts

The insect cuticle is a continuous, acellular product of the single-layered outer epithelium (the epidermis) (Hall, 1975; Adler, 1975; Denk-Lobnig & Martin, 2020), consisting of comparatively rigid sclerites and comparatively flexible conjunctivae that alternate across the cuticle. The differences in flexibility of different cuticular regions allow the sclerites to change position relative to each other, enabling insects to achieve a wide range of motion types (Mikó et al., 2013; Girón et al., 2023).

The number, shape, and pattern of the sclerite-conjunctiva system varies between taxa and has changed throughout the course of evolution. One notable difference among taxa is sclerite “fusion” or “division”; the former occurs when two or more sclerites merge due to the disappearance of the separating conjunctiva, the latter by splitting of a pre-existing single sclerite by the development of a conjunctiva across it. For instance, the single sclerite connected to the cupula in the male genitalia in Ichneumonidae (=gonostyle) has been interpreted as the result of the fusion of the harpe and the gonostipes, forming one single continuous structure, named gonoforceps by different authors (Peck, 1937a).

The appearance or disappearance of conjunctivae is why the term “complex” (e.g., gonostyle/volsella complex) was introduced by Ronquist & Nordlander (1989) and has been widely used for describing anatomical ontologies (Mikó et al., 2013; Aibekova et al., 2022). The term “anatomical complex” refers to a sclerite present in a particular taxon, which occupies a region that in other taxa is occupied by multiple sclerites. For instance, the volsella and the gonostyle are two different completely separate sclerites in the subfamily Labeninae (Ichneumonidae), but they are partially or entirely continuous in Mesochorinae.

Description format

To help researchers navigate the different terminologies in standard taxonomic descriptions and future evolutionary studies, we provide a detailed morphological treatment of Hymenoptera male genitalia elements using the following structure:

-

Labels –A list of synonymous labels employed by various authors is provided following the preferred term. The first author listed after the term is either the person who coined the term or the one who applied it for the first time in Hymenoptera, followed by authors who employed the term afterward. Newly proposed synonyms are marked with an asterisk (*).

-

Concept –A general, homology-free diagnosis of the element and its components with special emphasis on their connectedness and structural properties, i.e., epistemological recognition criteria.

-

Definition –The Aristotelian definition of the element. Aristotelian definitions are used to build ontologies as they represent universal statements (see Vogt, Bartolomaeus & Giribet (2022) for more discussion).

-

Discussion of terminology –The review of the usage of terms referring to the element within Hymenoptera with special emphasis on Ichneumonoidea.

-

Preferred term –the label that has been selected as preferred, using the above criteria.

-

Morphological variation in Ichneumonoidea –overview of the variation in the elements as observed from dissected specimens or as described in previous literature.

-

Comments –general comments on the anatomical elements.

Each of the main elements (abdominal sternum 9, cupula, gonostyle, volsella, and penisvalva) of the male genitalia can be composed of a single sclerite or divided into multiple sclerites. Sclerites can be further divided into regions (also called areas) with more or less well-defined boundaries. For the best modeling of this complex system, we listed these structures nested within each other. This should help the reader navigate across the different terms.

Main elements of the male genitalia are identified by a Roman numeral (e.g., GONOSTYLE=III); followed by another number referring to individual sclerites of the element (e.g., GONOSTIPES=III.1), and finally, a Latin letter identifies regions of the sclerite (e.g., PARAPENIS=III.1.a). For example, the parapenis (III.1.a) is an area of the gonostipes (III.1) which is one of the sclerites that compose the gonostyle (III).

A note of caution: in some dry specimens, regions can appear more definable and can be possibly misidentified as separate sclerites, instead of being simply areas of certain sclerites. Thus, wet specimens are critical for understanding where sclerites start and end and thus ontological alignment of terms.

Results

A review of Ichneumonoid male genitalia

With more than 48,000 described species, Ichneumonoidea is one of the largest superfamilies of Hymenoptera (Branstetter et al., 2018) and comprises roughly a third of all recognized species of Hymenoptera (Sharanowski et al., 2021). It is divided into two families, Braconidae (>21,000 spp.) and Ichneumonidae (>25,000 spp.) (Quicke, 2015; Yu, van Achterberg & Horstmann, 2016; Klopfstein et al., 2019; Sharanowski et al., 2021).

Many lineages of the superfamily show incredible external variation in the male genitalia. However, the genital morphology in Ichneumonoidea remains substantially undescribed for almost all of the 48,000 species, with the exception of the genus Netelia Gray (Ichneumonidae, Tryphoninae) (e.g., Townes, 1939; Konishi, 1991; Konishi, 1992; Konishi, 1996; Konishi, 2010; Bennett, 2015; Konishi, Chen & Pham, 2022). Some authors have included descriptions of the genitalia in occasional single species descriptions (e.g., Loan, 1974; Walker, 1994; Watanabe & Matsumoto, 2010; Watanabe, Taniwaki & Kasparyan, 2015; Sobczak et al., 2019; Brajković et al., 2010).

The first description of the male genitalia of Ichneumonidae was provided by Bordas (1893), who analyzed the internal and external genital organs of five taxa, while Peck (1937a) and Peck (1937b) provided the first, and so far only, extensive study of Ichneumonidae male genitalia, with 96 taxa analyzed and comments on muscles, sclerite movements, and homology statements. In Braconidae, Seurat (1898) and Seurat (1899) was the first to mention the genitalia, while Snodgrass (1941) briefly analyzed and compared them with those of Ichneumonidae. Subsequently, Alam (1952) provided a more detailed study on the skeleto-musculature for one species of the subfamily Braconinae, while Karlsson & Ronquist (2012) provided the first modern description of the male external genitalia of two braconid species in the subfamily Opiinae.

Despite the fact that Schulmeister (2003) demonstrated that male genitalia characters can be informative for the higher-level classification of basal Hymenoptera and that other authors have successfully applied these structures in genus-level phylogenetic studies within sawflies (Malagon-Aldana et al., 2021) and Apocrita (Andena et al., 2007; Owen et al., 2007; Mikó et al., 2013), external male genitalia are rarely employed in phylogenetic studies on Ichneumonoidea. Slightly more research has been devoted to the genital organs of Braconidae, but most, if not all, of these studies show inconsistent terminologies. Some cite synonymous terms that are no longer valid (as discussed by Schulmeister (2001); Schulmeister (2003)), and others associate a valid term with referring to a different sclerite.

The first suprageneric classification of Ichneumonidae using copulatory organs was proposed by Peck (1937b) (based on his previous work (Peck, 1937a)), who emphasized the importance of the abdominal sternum 9 (= subgenital plate). Likewise, Pratt (1939) discussed the genital characters of a subset of Ichneumonidae, providing the first (and only) key to the tribes based solely on male genitalia.

Various genera of Braconidae were analyzed by Tobias (1967), who was the first to explore differences between subfamilies, while the subfamily Aphidiinae was extensively studied by Tremblay (1979), Tremblay (1981) and Tremblay (1983). Quicke (1988) surveyed Braconinae, concluding that the characters could be potentially useful for higher-level classification in the subfamily. Later, Maetô (1996) assessed the inter-generic variation of external male genitalia in Microgastrinae, while more recently Brajković et al. (2010) and Žikić et al. (2011) did the same in Agathidinae.

Over the years, other authors have included male genitalia in their phylogenies of Ichneumonoidea or one of its two families (e.g., Wahl & Gauld, 1998) but the degree to which these characters have been employed is minimal. For instance, the recent morphological phylogenetic analyses of Ichneumonidae subfamilies by Bennett et al. (2019) included only four characters of the male terminalia, of which only two belong to the genital capsule. Reasons for the lack of use of male genitalic characters in Ichneumonoidea phylogenetics are unclear but possibly are due to: (1) the Ichneumonoidea classification system is mostly based on females and the association with males has been proven to be challenging; (2) males are rarely dissected, and genitalia characters have never been thoroughly assessed, nor they have been employed in taxonomic studies; and (3) rampant terminological inconsistencies, coupled with the overall complexity of the male genitalia, have discouraged researchers from exploring the male genitalia in Ichneumonoidea. This is why it becomes paramount to overcome at least one of these impediments, providing for the first time a complete assessment of the terminology.

Towards a unified terminology

The male reproductive organs of Hymenoptera are composed of internal and external structures, in continuity with each other (Schulmeister, 2001). The inner reproductive system is composed of the testis, vas deferens, seminal vesicle, accessory gland, and ductus ejaculatorius. The external male genitalia consist of five elements: (1) abdominal sternum 9; (2) cupula; (3) gonostyle; (4) volsella; and (5) penisvalva (Figs. 1, 2). Note that all structures of the external male genitalia and their historical terms are described in depth below (see ‘Methods and Results’). According to Schulmeister (2001) and Schulmeister (2003), there are also two other sclerites: (6) the median sclerotized style, which is a thin sclerite that lies on the median axis of the ventral side of the external genitalia between the two penisvalvae, and (7) the fibula ducti, which is a sclerite present in the proximal end of the ductus ejaculatorius.

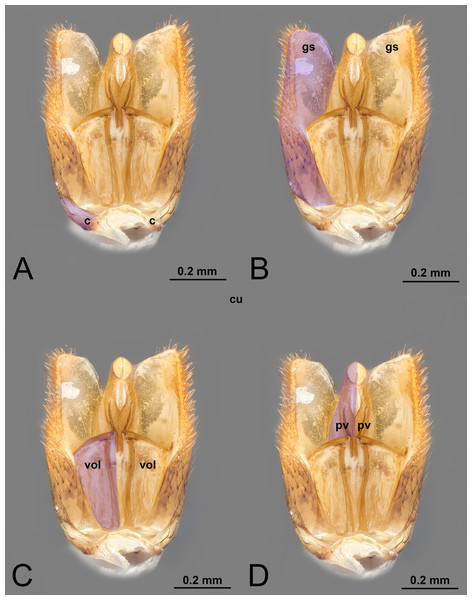

Figure 1: Ventral view of male genitalia of Melanichneumon lissorufus (Ichneumonidae: Ichneumoninae) with different elements highlighted as follow: (A) Cupula (c). (B) Gonostyle (gs). (C) Volsella (vol). (D) Penisvalva (pv).

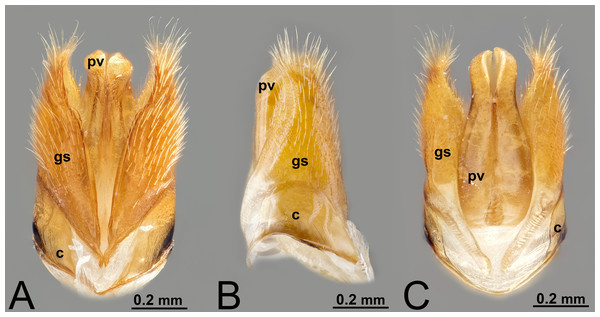

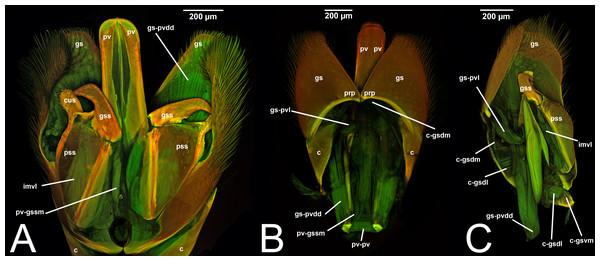

Figure 2: Male genitalia of Labena grallator (Ichneumonidae: Labeninae). (A) Ventral view. (B) Lateral view. (C) Dorsal view.

The elements of the male genitalia are interconnected through a network of muscles that move the sclerites individually or in conjunction (Duncan, 1939; Snodgrass, 1941; Snodgrass, 1957; Michener, 1956; Schulmeister, 2001; Schulmeister, 2003; Mikó et al., 2013). Four major muscle groups have been identified within Hymenoptera: (1) abdominal sternum 9 to cupula, which are usually three muscles that control the movement of the entire genital capsule; (2) cupula to gonostyle, which are usually four distinct bundles that control the movement of the gonostyles; (3) gonostyle to volsella, which can be up to three distinct muscles that generally control the lateral motion of the volsella and the opening and closing of the apical clasping structure; (4) gonostyle to penisvalva, which usually consist of five distinct bundles, and control the motion of the penisvalvae.

ABDOMINAL STERNUM 9

I. ABDOMINAL STERNUM 9 (S9, Figs. 3A, 4A, 4C)

ninth abdominal sternite by Worthley (1924); Snodgrass (1935).

subgenital plate by Snodgrass (1935); Watanabe & Matsumoto (2010).

*nono urotergite by Tremblay (1979); Tremblay (1981); Tremblay (1983).

hypopygium by Pratt (1939); Nichols (1989); Karlsson & Ronquist (2012); Broad, Shaw & Fitton (2018); Bennett et al. (2019).

hypopygidium by Nichols (1989); Schulmeister (2001).

hypandrium by Nichols (1989); Peck (1937a); Peck (1937b); Karlsson & Ronquist (2012).

annular lamina by Nichols (1989).

hypotome by Nichols (1989).

ninth sternal lobe by Nichols (1989).

poculus byNichols (1989).

postgenital plate by Nichols (1989).

metasomal sternum viii by Brothers & Carpenter (1993).

abdominal sternum 9 by Karlsson & Ronquist (2012).

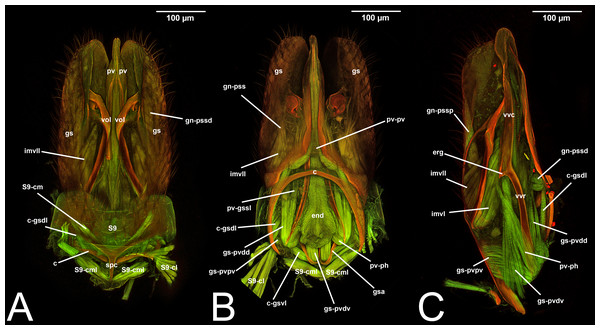

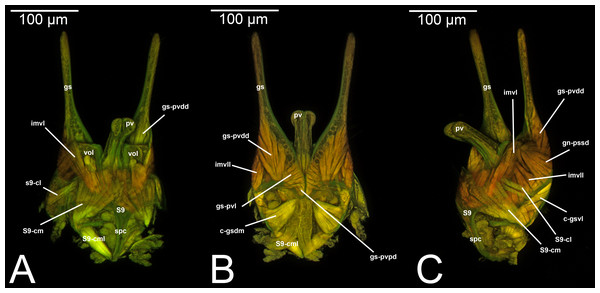

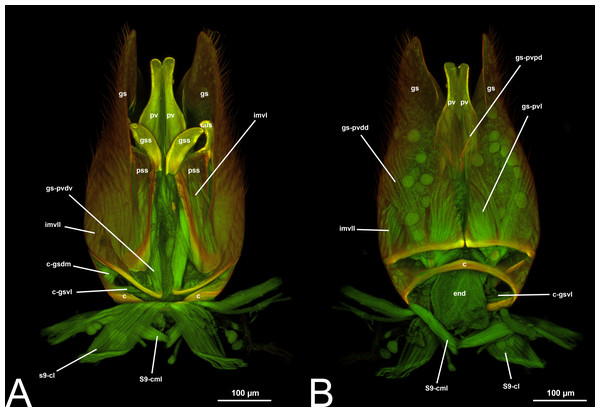

Concept. The abdominal sternum 9 is the ventral part of the ninth abdominal segment and connects the abdominal segments to the genital sclerites. Although not a direct component of the male genitalia, the abdominal sternum 9 has a strong association with the cupula, by means of three major muscles: the medial (S9-cml), the mediolateral (S9-cm), and the lateral S9-cupulal (S9-cl) muscle (Figs. 3A–3B, 4A–4B, 5A–5B; Tables 3–4). These muscles allow the protraction and retraction of the entire male genitalia. The abdominal sternum 9 is usually produced proximo-medially into a process called the spiculum (spc, Figs. 3A, 4A, 4C), which is an apophysis that corresponds to the site of origin of the mediolateral (S9-cml) and medial S9-cupulal (S9-cm) muscles (Figs. 3A–3B, Figs. 4A–4B).

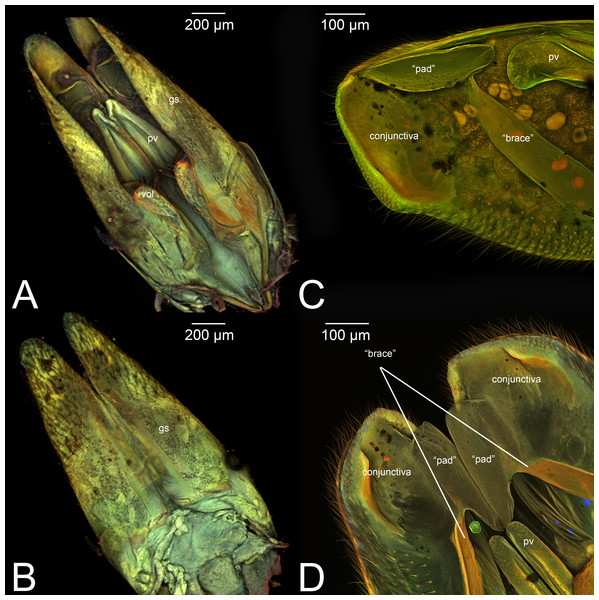

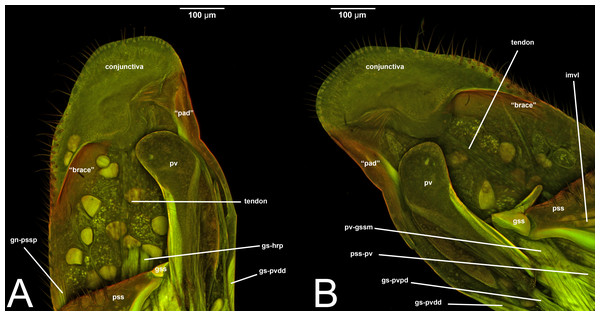

Figure 3: CLSM volume rendered images of male genitalia of Temelucha sp. (Ichneumonidae: Cremastinae). (A) Ventral view. (B) Dorsal view. (C) Median view.

Figure 4: CLSM volume rendered images of male genitalia of Mesochorus sp. (Ichneumonidae: Mesochorinae). (A) Ventral view. (B) Dorsal view. (C) Lateral view.

Figure 5: CLSM volume rendered images of male genitalia of Xorides eastoni (Ichneumonidae: Xoridinae). (A) Ventral view. (B) Dorsal view.

Definition. As defined by the HAO, the abdominal sternum 9 is the abdominal sternum that is located on abdominal segment 9 (Table 2).

Discussion of terminology. Many of the terms employed are either variations of abdominal sternum 9 (e.g., ninth sternal segment) or have been rarely employed (e.g., poculus). However, one of the most popular terms employed is hypopygium, which has been employed to refer to the most posterior sternite in different insect orders. However, from a morphological perspective, the hypopygium can be confusing. In fact, it has been used within Hymenoptera to refer to the abdominal sternum 7 in females (the last observable sternite in females) or to the abdominal sternum 9 in males (the last observable sternite in males) (e.g., Karlsson & Ronquist, 2012; Broad, Shaw & Fitton, 2018; Bennett et al., 2019). Moreover, hypopygium can also refer to different structures in different orders: in Diptera it refers to the terminalia, in Lepidoptera to the multiple sclerites fused together, while in Cicadomorpha (Hemiptera) it is used for the fused tergal and pleural parts of segment 9 (Tuxen, 1956). For these reasons, we strongly encourage using abdominal sternum 9, which fulfills criterion 1 and 4.

Within Ichneumonoidea, hypopygium has been widely employed (e.g., Pratt, 1939; Karlsson & Ronquist, 2012; Broad, Shaw & Fitton, 2018; Bennett et al., 2019), while hypandrium was employed only by Peck (1937a); Peck (1937b) and by Karlsson & Ronquist (2012). Many other studies tend to exclude this sclerite as being part of the male genitalia (e.g., Quicke & van Achterberg, 1990).

Preferred term. Abdominal sternum 9.

Morphological variation in Ichneumonoidea. According to several authors, the abdominal sternum 9 varies across the Ichneumonoidea. It has been used for differentiating genera (e.g., Heinrich, 1961) and employed in phylogenetic reconstruction (e.g., Bennett et al., 2019). There are several areas of variation: (1) the distal margin, which can be elongated, flat, or concave (Heinrich, 1961; Bennett et al., 2019); (2) the shape of the spiculum, which can be extremely elongated (spc, Figs. 3A, 4A, 4C) or reduced, wide or thin (Peck, 1937a); (3) in the overall shape of the sclerite (see the image in Peck, 1937a, p. 246).

II. CUPULA

Concept. The cupula is an unpaired sclerite located at the proximal basis of the male genitalia. Different authors (see below in the Discussion of terminology) have consistently identified (with different names) an unpaired sclerite surrounding the proximal basis of the male genitalia. The cupula delimits a basal opening called the foramen genitale (Snodgrass, 1941; Schulmeister, 2001), and is connected via three muscles to the abdominal sternum 9 and via four muscles to the gonostyle (Table 4).

Definition. As defined by the HAO, the cupula is the sclerite that is connected via conjunctiva and attached via muscle to the abdominal tergum 9 and the gonostyle/volsella complex (Table 2).

Discussion of terminology. At least 21 terms have been introduced to refer to the cupula. Of these, only four (basal ring, cupula, gonobase, gonocardo) are worth discussing as they have been employed more than once after their introduction. All the other terms (see above), are rejected as they do not conform to criterion 2.

The first author to identify the basal sclerites of the genital organs in Hymenoptera was Audouin (1821), who proposed the term cupule (later modified to cupula by Birket-Smith (1981)) to refer to an unpaired sclerite, which the author called the “support commun [= general support]”.

In 1872, Thomson introduced cardo as a new term for the same structure after he studied the genus “Bombis [sic] [= Bombus]” and identified a basal capsule divided into two halves (Thomson, 1872). However, Crampton (1919) realized that cardo was also used for the basal sclerite of the maxillae in insects (rejected by criterion 4), and he proposed to replace cardo with gonocardo without realizing that another available term (cupule) has been already proposed. In the same work, Crampton (1919) introduced an additional term for the same sclerite, basal ring. This latter term, however, refers also to two different structures in two other orders: in Protura, it is used to refer to a basal structure of the male genitalia, while in Diptera, it is used for the combination between tergite and sternum IX (Tuxen, 1970). Since the term was first introduced in Diptera, and it is not equivalent to the one in Hymenoptera, basal ring should not be considered the preferred term (rejected by criterion 4).

Later on, Michener (1944), following the periphallic theory, introduced gonobase, and subsequently, Michener (1956) formally synonymized gonocardo under gonobase, using the same rationale. Unfortunately, both authors failed to notice that the term gonobase corresponds to the non-equivalent gonobasis in basal insects (e.g., Willman, 1998; Schulmeister, 2001), and, therefore, it should also not be used as the preferred term (rejected by criterion 4).

It must be noticed that there is a cupula also in Lepidoptera that was introduced by Field (1950) for a pair of pouches located on the 7th abdominal sternite of females (Tuxen, 1956). These two structures are not analogous to the cupula of Hymenoptera (HAO:0000238, see comments). Due to the date of introduction (the cupula of Audouin (1821) has been introduced before the cupula of Field (1950)) and due to the fact that the term has been specifically introduced in Hymenoptera, the cupula of Audouin (1821) can be retained and used as the preferred label for this sclerite (approved by criterion 3).

Within Ichneumonoidea, a number of authors used the term gonobase referring to the cupula (Tremblay, 1979; Tremblay, 1981; Tremblay, 1983; Quicke & van Achterberg, 1990; Belokobylskij, Zaldivar-Riveron & Quicke, 2004), and only two used gonocardo (Peck, 1937a; Peck, 1937b; Pratt, 1939) and basal ring (Alam, 1952; Konishi, 2005). As far as we know, the term cupula was applied to Ichneumonoidea only by Schulmeister (2003).

Preferred term. Cupula.

Morphological variation in Ichneumonoidea. Across Ichneumonoidea, the cupula has undergone repeated reduction, sometimes within a subfamily. In Labena grallator (Say, 1845) (Ichneumonidae, Labeninae), Xorides eastoni (Rohwer, 1913) (Ichneumonidae, Xoridinae), and Coelichneumon Thomson, 1896 (Ichneumonidae, Ichneumoninae), the cupula is well developed, especially on the lateral side (Figs. 2A–2B, 6A), while in Mesochorus Gravenhorst, 1829 (Ichneumonidae, Mesochorinae) and Melanichneumon Thomson, 1893 (Ichneumonidae, Ichneumoninae) (Fig. 1A) it is significantly reduced. Similar variations have also been observed by previous authors. Peck (1937b) described a ventrolaterally unusually broad cupula in Megarhyssa macrura Linnaeus, 1771 (Ichneumonidae, Rhyssinae) and Banchus falcatorius (Fabricius, 1775) (Hymenoptera, Banchinae), while Pratt (1939) noticed variations between members of the same subfamily, with Delomerista Förster, 1869, and Perithous Holmgren, 1859 (Ichneumonidae, Pimplinae) showing a well-developed and an extremely reduced cupula, respectively. The same pattern was observed in Braconidae, with some subfamilies (e.g., Braconinae and Doryctinae) bearing a very elongated cupula (Figs. 77. 78 in Quicke & van Achterberg, 1990, p. 62), while in others (e.g., Histomerinae) the same sclerite is reduced (Fig. 73 in Quicke & van Achterberg, 1990, p. 61).

Comments on cupula. Vilhelmsen (1997) identified the cupula as a hymenopteran synapomorphy, but this result will likely require further investigation. In fact, other insect groups have a sclerite located basally to the rest of the sclerites and connected to the abdominal sternum 9 (e.g., the phallobase in Coleoptera, see Snodgrass, 1957, p. 30, fig. C).

A final note concerns Boudinot (2018), while he rejected the phallic theory, he did not introduce a new term for the cupula, but considered the structure a part of the fragmented base of genital appendages.

III. GONOSTYLE

Concept.The gonostyle and the volsella, constitute the gonostyle/volsella complex. The gonostyle is the outermost structure of the male genitalia that is connected proximally with the cupula and medially with the volsella. When two clearly separated sclerites are present (the proximal gonostipes and the distal harpe), the entire structure has been named in different ways, mainly paramere, gonostyle, latimere, and stipes (see the list of synonymous terms above). However, when only one sclerite is present, only one term, gonoforceps, has been employed. Below we give an extensive explanation of why this has happened and why we propose gonostyle as the preferred term. Proximally, the gonostyle is elongated into two brace-like apodemes, called the gonostipital arms (gsa, Fig. 3B). At the tip of these, another apodeme, called apex gonostipitis, allows the insertion of two muscles, the proximoventral (gs-pvpv) and the distoventral gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle (gs-pvdv) (Figs. 3B–3C, 5A; Tables 3–4). Historically a dorsomedial area has been identified, called parapenis (see below for an extensive treatment) that functions as a site of origin for the proximodorsal (gs-pvpd) and distodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscle (gs-pvdd) (Figs. 3B–3C, 4A–4C, 6B–6C, 7B; Tables 3–4).

Definition. As defined by the HAO, the gonostyle is the anatomical cluster that is composed of sclerites located distally of the cupula, dorsoventrally of the volsella, and that surrounds the aedeagus (Table 2).

Discussion of terminology. At least 12 terms have been introduced to refer to the gonostyle. Of these, five (paramere, gonostyle, latimere, gonoforceps, claspers) are worth discussing as they have been employed more than once after their introduction. The other terms (see above), are rejected as they do not conform to criterion 2.

Among the terms mentioned above, paramere has been the most widely used to refer to this cluster of sclerites of the male genitalia. The term has been applied across different insect orders (e.g., Coleoptera), and within Hymenoptera is a renowned case of homonymy (Yoder et al., 2010). Applied for the first time in Hymenoptera by Verhoeff (1832) to refer to the gonostipes+harpe+volsella, the concept of paramere changed to refer only to the penisvalva (Beck, 1933; Peck, 1937b), then to the entire male genitalia (cupula excluded) (Wheeler, 1910), then only to the harpe (Snodgrass, 1941; Königsmann, 1976), and finally to gonostipe+harpe (Snodgrass, 1957). According to this already rampant confusion, Peck (1937a) coined a new term, gonoforceps, to refer to those specific cases in which the harpe and gonostipes are not distinguishable, and only a single continuous sclerite is present. Gonoforceps has been introduced specifically in Hymenoptera and has been very successfully applied in Ichneumonoidea. Later on, probably for the need to refer generally to a structure that could either be composed of two sclerites or just one, Bohart & Menke (1976) introduced the term gonostyle defining it as the “outermost paired appendages of male genitalia, sometimes divided into basistyle and dististyle” (see below for these last two terms).

Schulmeister (2001) first identified the confusion regarding homonyms of the term paramere and chose to reject its use. However, at the same time, she also introduced a new term, latimere, to identify the anatomical cluster formed by the gonostipes+harpe, maintained gonoforceps when the two sclerites were not distinguishable, and ignored the term gonostyle.

More recently, Mikó et al. (2013) employed the term gonoforceps in Ceraphronoidea when only one sclerite was discernible, but when the harpe and the gonostipes were present (as it is the case for the majority of the species), they employed the term gonostyle. On the other hand, Boudinot (2013) used paramere, instead of gonoforceps, even though a clear distally delimited sclerite (the harpe) is not present.

The term claspers were applied by Townes (1969a) to Ichneumonidae to refer to a special case in which the gonostyle is elongated, forming a rod (Figs. 4A–4C).

Among these many terms and concepts, it is not easy to identify which are preferred. However, some conclusions can be drawn. Following Schulmeister (2001); Schulmeister (2003), we reject the term paramere based on criterion 1 as it does not best represent the skeletal structure. At the same time, claspers should be rejected because, as pointed out by Tuxen (1956), the term is widely used in many different other insect orders to refer to widely different structures, some of which are not homologous to the gonostyle (rejected by criterion 4). The term latimere also can be rejected as it has not been employed in any other work after Schulmeister (2001); Schulmeister (2003) (rejected by criterion 2). Between gonoforceps and gonostyle, we suggest the latter as it better represents this skeletal area (fulfilling criterion 1). In fact, if the presence of the single sclerite has evolved through a fusion of gonostipes and harpe, it would be equivalent to the entire gonostyle, while if evolution resulted in a loss of the harpe, the gonoforceps would be equivalent to the gonostipes alone (Schulmeister, 2001). In both cases, the use of gonoforceps is unwarranted as there is no need for the employment of different terms to refer to a structure that is equivalent to either one or two sclerites. We certainly understand the “tradition” in using gonoforceps, but we also believe that to be able to move Hymenoptera and Ichneumonoidea into the phenomic era and allow future data mining for morphological features, it is better to avoid multiple terms for the same structure or group of sclerites, and employ accurate anatomical concepts (Girón et al., 2023). In this framework, the original definition of gonostyle proposed by Bohart & Menke (1976) allows the employment of the term in multiple cases: (1) when a clear delimitation between harpe and gonostipes is present; (2) when a clear delimitation between harpe and gonostipes is absent (the gonoforceps; see below for more details); and (3) when a delimitation between harpe and gonostipes is present, but it is not complete (see Peck (1937a)). Therefore, we strongly encourage the employment of the term gonostyle and use it as the preferred label.

As a side note, there is one term that was recently introduced by Mikó et al. (2013): the gonostyle/volsella complex. It refers to the anatomical cluster composed of the sclerites located distally of the cupula and surrounding the aedeagus. We encourage the employment of this term especially when there is no clear delimitation between the volsella and the gonostyles.

Peck (1937a) and Peck (1937b) introduced the term gonosquama within the Ichneumonoidea. However, the term has not been used since then. On the other hand, the term paramere has been employed several times. Depending on the authors, paramere was used either to refer to the single sclerite that we now identify as a gonostyle (Pratt, 1939; Tobias, 1967; Quicke & van Achterberg, 1990; Belokobylskij, Zaldivar-Riveron & Quicke, 2004; Žikić et al., 2011; Broad, Shaw & Fitton, 2018; Brajković et al., 2010) or to indicate just its distal part (Alam, 1952; Tremblay, 1979; Tremblay, 1981; Tremblay, 1983). The term gonoforceps, even though introduced purposely for Ichneumonidae, has only been used by three authors (Peck, 1937a; Peck, 1937b; Karlsson & Ronquist, 2012; Bennett et al., 2019). Finally, claspers, has been widely used in Ichneumonidae (e.g., Townes, 1969a; Townes, 1969b; Townes, 1969c; Townes, 1971), especially when referring to the gonostyle of members in the subfamily Mesochorinae (e.g., Dasch, 1971; Lee, 1991).

Preferred term. Gonostyle.

Morphological variation in Ichneumonoidea. Among the Ichneumonoidea herein surveyed and analyzed in the literature, the gonostyle show a small degree of variability. Within Ichneumonidae, the entire subfamily Mesochorinae (Figs. 4A–4C), and the genera Lusius Tosquinet, 1903 (Ichneumoninae) (DDP personal observation, 2023) and Nematopodius Granvenhorst, 1829 (Cryptinae) (G. Broad, personal communication, 2023) show a strong reduction of the apical part of the gonostyle, while Pratt (1939) found an apical knob in Rhyssinae (Ichneumonidae), hereby confirmed in Rhyssa persuasoria (Fig. 6C). Clear gonostipital arms are present in Temelucha (Fig. 3B), while they are inconsistent in Mesochorus (Fig. 4). In some Braconidae subfamilies (e.g., Exothecinae), these sclerites likely underwent a shortening, exposing the penisvalvae and part of the volsella (Figs. 75, 76 in Quicke & van Achterberg, 1990, p. 61).

| III.1. GONOSTIPES (Fig. 9A inMikó et al., 2013, p. 275) |

| stipes by Thomson (1872); Zander (1900); Wheeler (1910). |

| gonostipes by Crampton (1919); Peck (1937a); Peck (1937b); Ross (1937); Ross (1945); Schulmeister (2001); Schulmeister (2003); Mikó et al. (2013). |

| pièce principale by Boulangé (1924). |

| coxopodite by Beck (1933). |

| basal part of forceps by Snodgrass (1941). |

| basiparamere by Snodgrass (1941). |

| lamina parameralis by Snodgrass (1941). |

| *parameral plate by Snodgrass (1941). |

| gonocoxite by Michener (1944); Michener (1956). |

| basimere by Snodgrass (1941); Boudinot (2013). |

| basal part of stipes by Birket-Smith (1981). |

| section 2 by Smith (1969). |

| basistyle by Bohart & Menke (1976). |

| *basiparamere by Brajković et al. (2010). |

| *gonocoxa by Boudinot (2013). |

Concept. The gonostipes is the proximal sclerite composing the gonostyle. It has received several names, of which only one was applied to refer to two distinct concepts. When firstly introduced, the term gonostipes was applied to the gonostipes+volsella (Crampton, 1919), and only subsequently (e.g., Peck, 1937a; Peck, 1937b; Ross, 1937; Ross, 1945; Königsmann, 1976) it was used to refer only to the gonostipes, excluding the volsella. The latter is the concept that has been more broadly and consistently employed (Schulmeister, 2001).

Definition. As defined by the HAO, the gonostipes is the sclerite that is located dorsolaterally on the gonostyle/volsella complex, and is connected to the distal margin of the cupula, to the proximal margin of the harpe, and to the lateral margin of the volsella (Table 2).

Discussion of terminology. At least 15 terms have been introduced to refer to the gonostipes. Of these, only three (stipes, gonostipes, basimere) are worth discussing as they have been employed more than once after their introduction. All the other terms (see above), are rejected as they do not conform to criterion 2.

The term stipes was introduced by Thomson (1872) to an area or sclerite of the male genitalia of Bombus Latreille (Hymenoptera: Apidae). As noted by Schulmeister (2001), it is not clear if he referred to the volsella (which is extremely reduced in Bombus) or to the proximal sclerite of the gonostyle. Crampton (1919) replaced Thomson’s (1872) stipes with gonostipes acknowledging the fact that stipes is also employed to describe the appendages that bear the maxillary palps (rejected by criterion 4).

Later, Michener (1944), following the periphallic theory, introduced the term gonocoxite, and, in 1957, Snodgrass employed the term basimere (firstly introduced by Crampton (1942) in Diptera) to refer to the gonostipes (Snodgrass, 1957), a term that was also preferred by Boudinot (2013).

Among these terms, we strongly encourage the use of gonostipes, which is not only the oldest (fulfilling criterion 3) but also better represents the skeletal structure (fulfilling criterion 1). In fact, gonocoxite has never been employed after Michener (1956), and, as already explained by Schulmeister (2001), the term implies a homology with the coxa, and thus should be avoided (rejected by criteria 2 & 4). The term basimere is strongly connected to the concept of paramere (being its proximal sclerite), which, as we argued above, should be avoided (see under Discussion of terminology of the Gonostyle) (rejected by criteria 1). As already noticed by Schulmeister (2001), gonostipes is a very well-known term and even though at its introduction, it was applied to the gonostipes+volsella complex, the modern concept of the term refers to the proximal sclerite of the gonostyle.

For the above reasons, the term gonostipes should be considered the preferred term.

The application of the term gonostipes is minimal in Ichneumonoidea due to the lack of a clear delimitation between the proximal sclerite and the harpe in most of the taxa. Only two authors used gonostipes (Peck, 1937a; Peck, 1937b; Tremblay, 1979; Tremblay, 1981; Tremblay, 1983).

Preferred term. Gonostipes.

Morphological variation in Ichneumonoidea. From our dissections, a clear delimitation of sclerites of the gonostyle is not evident in Ichneumonidae. However, Peck (1937a) acknowledged the presence of an articulated appendage in few ichneumonids. Further analyses, incorporating Peck’s (1937a) taxa, will be required to better understand the issue.

III.1.a. PARAPENIS (prp, Figs. 6B, 7B)

parapenis by Crampton (1919); Boulangé (1924); Schulmeister (2001);

Schulmeister (2003); Boudinot (2013); Koch & Liston (2017).

manubrium by Crampton (1919).

*praeputium by Crampton (1919).

*parapenis plate by Crampton (1919).

parapenial lobe by Evans (1950).

lobi parapenialis by Priesner (1966).

Concept. The parapenis is an area of the gonostipes located dorsomedially that has been mostly identified in basal Hymenoptera and very rarely in Apocrita (e.g., Schulmeister, 2003). The area functions as a site of origin for proximodorsal (gs-pvpd) and distodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscles (gs-pvdd) (Tables 3–4). Only one concept (the original) has been applied to this area.

Definition. As defined by the HAO, the parapenis is the area that is the dorsomedial part of the gonostipes and is the site of origin of the distodorsal and proximodorsal gonostyle/volsella complex-penisvalval muscles (Table 2).

Discussion of terminology. Crampton (1919) introduced four terms to identify the area of gonostipes. Of these, only one, parapenis, has been employed more than once after its introduction by Boulangé (1924) and Schulmeister (2001); Schulmeister (2003). The other two terms, parapenial lobe, and lobi parapenialis, have not been employed further (rejected by criterion 2). Overall, the term parapenis has not been widely used, probably due to low variation across Apocrita, and to the lack of clear boundaries that delimit it. Boudinot (2013) decided not to use the term in Formicidae due to uncertain homology.

Within Ichneumonoidea, the term has not been employed, and the area has never been identified.

Figure 6: CLSM volume rendered images of male genitalia of Rhyssa persuasoria (Ichneumonidae: Rhyssinae). (A) Ventral view. (B) Dorsal view. (C) Median view.

Preferred term. Parapenis.

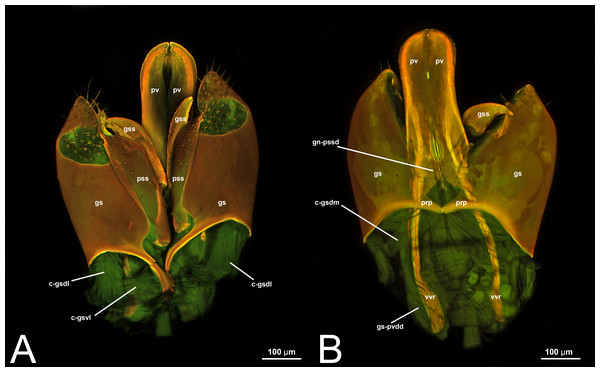

Morphological variation in Ichneumonoidea. According to Schulmeister (2003), the parapenis of Ichneumonidae is not set off from the rest of the gonostipes. In our observations, this is true for Temelucha (Fig. 3B), Labena grallator (Fig. 2A), Mesochorus (Fig. 4B), and Netelia (Fig. 10B), but it is produced in the middle in Pomeninae (Fig. 7B) and Rhyssinae (Fig. 6B).

Figure 7: CLSM volume rendered images of male genitalia of Neoxorides pilosus (Ichneumonidae: Poemeniinae). (A) Ventral view. (B) Dorsal view.

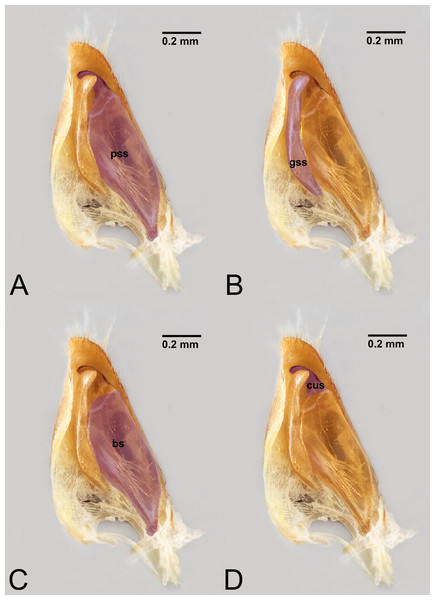

Figure 8: Median view of volsella of Labena grallator (Ichneumonidae: Labeninae) with different elements highlighted as follow: (A) Parossiculus (pss). (B) Gonossiculus (gss). (C) Basivolsella (bas). (D) Cuspis (cus).

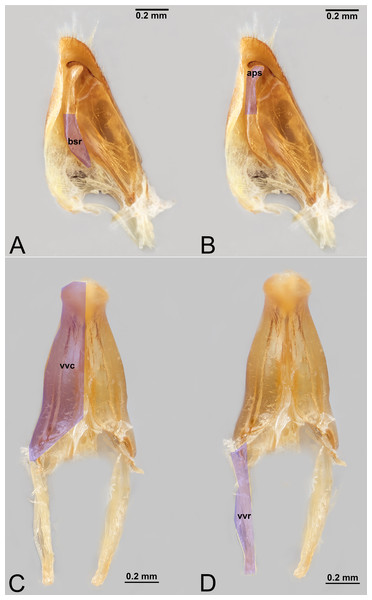

Figure 9: Male genitalia of Labena grallator (Ichneumonidae: Labeninae) with different elements highlighted as follow: (A–B) Volsella, median view. (A) Basiura (bsr). (B) Apiceps (aps). (C–D) Penisvalva, ventral view. (C) Valviceps (vvc). (D) Valvura (vvr).

Figure 10: CLSM volume rendered images of male genitalia of Netelia sp. (Ichneumonidae: Tryphoninae). (A) Ventral view. (B) Dorsal view. (C) Gonostyle, right apical view. (D) Gonostyle, apical view.

| III.2. HARPE (Fig. 9A inMikó et al., 2013, p. 275) |

| harpe by Crampton (1919); Schulmeister (2001); Schulmeister (2003); Mikó et al. (2013). |

| distal segment of gonopod by Crampton (1919). |

| palette by Boulangé (1924). |

| gonosquama by Peck (1937a); Peck (1937b). |

| paramere (part.) by Snodgrass (1941); Michener (1944); Alam (1952); Michener (1956); Königsmann (1976). |

| gonostylus by Michener (1944); Michener (1956). |

| harpes [sic] by Ross (1945); Wong (1963); Königsmann (1976). |

| telomere by Snodgrass (1957); Boudinot (2013). |

| harpago by Snodgrass (1957); Yoshimura & Fisher (2011). |

| squama by Townes (1957). |

| disistyle by Bohart & Menke (1976). |

| harpide by Audouin (1821); Birket-Smith (1981). |

| *paramero by Tremblay (1979); Tremblay (1981). |

| *lobo paramerale by Tremblay (1981); Tremblay (1983). |

| ventral paramere by Gobbi & Azevedo (2016). |

| *stylus by Boudinot (2018). |

Concept. The harpe is the distally located sclerite of the gonostyle and is articulated via muscle with the gonostipes. On the harpe of Xyelidae, Pamphiliidae, Megalodontesidae, Siricidae, and Xiphydriidae, there is a conjunctiva called the gonomacula which seems to function as a suction cup (Schulmeister, 2001). Despite the many different terms applied to this sclerite, there has not been confusion regarding its identification and concept.

Definition. As defined by the HAO, the harpe is the sclerite that is located distally on the gonostyle/volsella complex and does not connect to the cupula nor to the volsella by conjunctiva or muscles (Table 2).

Discussion of terminology. At least 16 terms have been introduced to refer to the harpe. Of these, only five (harpe, harpago, harpide, paramere, telomere) are worth discussing as they have been employed more than once after their introduction. All the other terms (see above) are rejected as they do not conform to criterion 2.

The first to name the distal sclerite of the gonostyle was Crampton (1919), who introduced the term harpe. Subsequently, Peck (1937a) acknowledged the presence of an articulated appendage in a few ichneumonids, which he called gonosquama, a term that has not been used since then (rejected by criterion 2). Snodgrass (1941) decided to use paramere to refer only to the harpe, while Ross (1945), followed by subsequent authors (e.g., Wong, 1963; Königsmann, 1976) used the plural of harpe (harpes) to refer to the singular sclerite (and not to two sclerites). This is unwarranted and should be treated as a misspelling of harpe. In 1957, Snodgrass employed the term telomere (replacement for distamire introduced by Crampton (1942) in Diptera) to refer to the harpe (Snodgrass, 1957), a term that was also preferred by Boudinot (2013). In the same work in which he introduced telomere, Snodgrass (1957) introduced another synonym, harpago, for the same structure. As far as we know, the latter term has been used only once after its introduction and can be rejected following criterion 2.

An interesting case is the term harpide, which was introduced by Audouin (1821) and then employed by Birket-Smith (1981) to replace harpe. However, the term, as explained by Schulmeister (2001), was initially introduced by Audouin (1821) to identify a structure (not clear which one as there is no description nor images of it) of the male genitalia of bumblebees. Since bumblebees do not have a distally articulated sclerite, the harpide cannot refer to the harpe. Therefore, not only is harpide a synonym of harpe but it has been improperly applied. Of all these terms, we recommend the use of harpe, which is the oldest (fulfilling criterion 3) and that best represents the skeletal structure (fulfilling criterion 1). In fact, paramere, as we already discussed previously (see under Discussion of terminology of the gonostyle), suffers from extensive homonymy, and we strongly discourage its use (see also discussion in Schulmeister (2001)). At the same time, the term telomere is connected to the concept of paramere (being its distal sclerite), and therefore we also discourage its use.

As far as we know, the term harpe has never been used in Ichneumonoidea, and only Peck (1937a) employed the term gonosquama within Ichneumonidae (see below for more details).

Preferred term. Harpe.

Morphological variation in Ichneumonoidea. From our dissections, a clear delimitation of two individual sclerites is not evident in Ichneumonidae. However, Peck (1937a) acknowledged the presence of an articulated appendage in a few ichneumonids. Further analyses, incorporating Peck’s (1937a) taxa, will be required to better understand the issue.

Comments on gonostyle and its associated elements. Schulmeister (2001) considered the absence of a harpe as a synapomorphy of the Vespina (Orussidae + Apocrita) and concluded that even when a distally delimited sclerite on the gonostyle is present in the Apocrita, it is probably not homologous with the harpe because there would be no associated musculature. However, Mikó et al. (2013) found a musculated harpe in some Ceraphronoidea and Trigonaloidea (both Apocrita) even though the arrangements of these muscles are different from that of the lower Hymenoptera. Their discovery was not enough to deduce homology of the harpe between Apocrita and lower Hymenoptera. Boudinot (2013) also found intrinsic muscles in approximately the same position in Formicidae.

Figure 11: CLSM volume rendered images of male genitalia of Netelia sp. (Ichneumonidae: Tryphoninae). (A) Right gonostyle, median view. (B) Left gonostyle, median view.

It must be noted that Boudinot (2018) rejected the term paramere sensu Snodgrass (1957) because it was explicitly introduced within the phallic theory framework, and he instead employed the term gonopods for the same structures following the conclusion from the coxopod theory. Moreover, according to the same author, the gonocoxa (=gonostipes in the phallic theory), which is a fragment of the apical part of the sternum IX, fragmented a second time, forming the parossiculus (see below, under Volsella). According to this view, the parossiculus is just a secondary fragmentation of the gonostipes rather than part of the volsella. Boudinot (2018) also homologized the harpe with stylus, which he considered to have separated from the phallic apparatus (=aedeagus, see under Penisvalvae). This makes the stylus a sclerite with a completely different origin than the gonostyle. Boudinot (2018) did not provide any evidence or comments for the formation of a single sclerite.

IV. VOLSELLA

IV. VOLSELLA (vol, Figs. 1C, 3A, 4A, 5A, 6A, 6C, 7A8A–8B, 9A–9B, 10A, 11)

volsella by Dufour (1841); Peck (1937a); Peck (1937b); Pratt (1939); Michener (1944); Ross (1945); Alam (1952); Michener (1956); Snodgrass (1941); Snodgrass (1957); Scobiola (1963); Tobias (1967); Königsmann (1976); Johnson (1984); Olmi (1984a); Olmi (1984b); Quicke & van Achterberg (1990); Schulmeister (2001); Schulmeister (2003); Konishi (2005); Žikić et al. (2011); Karlsson & Ronquist (2012); Boudinot (2013); Mikó et al. (2013); Broad, Shaw & Fitton (2018); Brajković et al. (2010)

innere Haltzange by Enslin (1918).

tenette by Snodgrass (1941).

ossicle by Ross (1945).

section 3 by Smith (1969).

section 3 of gonocoxite by Schulmeister (2001).

Concept. The volsella, together with the gonostyle, constitute the gonostyle/volsella complex, and it lies between the gonostipes and the penisvalva. Overall, the volsella consists of two sclerites: (1) the gonossiculus, which is located distoventrally (gss, Fig. 8B); and (2) the parossiculus, located proximally (pss, Fig. 8A). The parossiculus is further divided into a basal and distal area: the basivolsella (bs, Fig. 8C) and the cuspis (cus, Fig. 8D), respectively.